Actionable Genomic Alterations in Cancer: From Discovery to Targeted Therapies and Clinical Validation

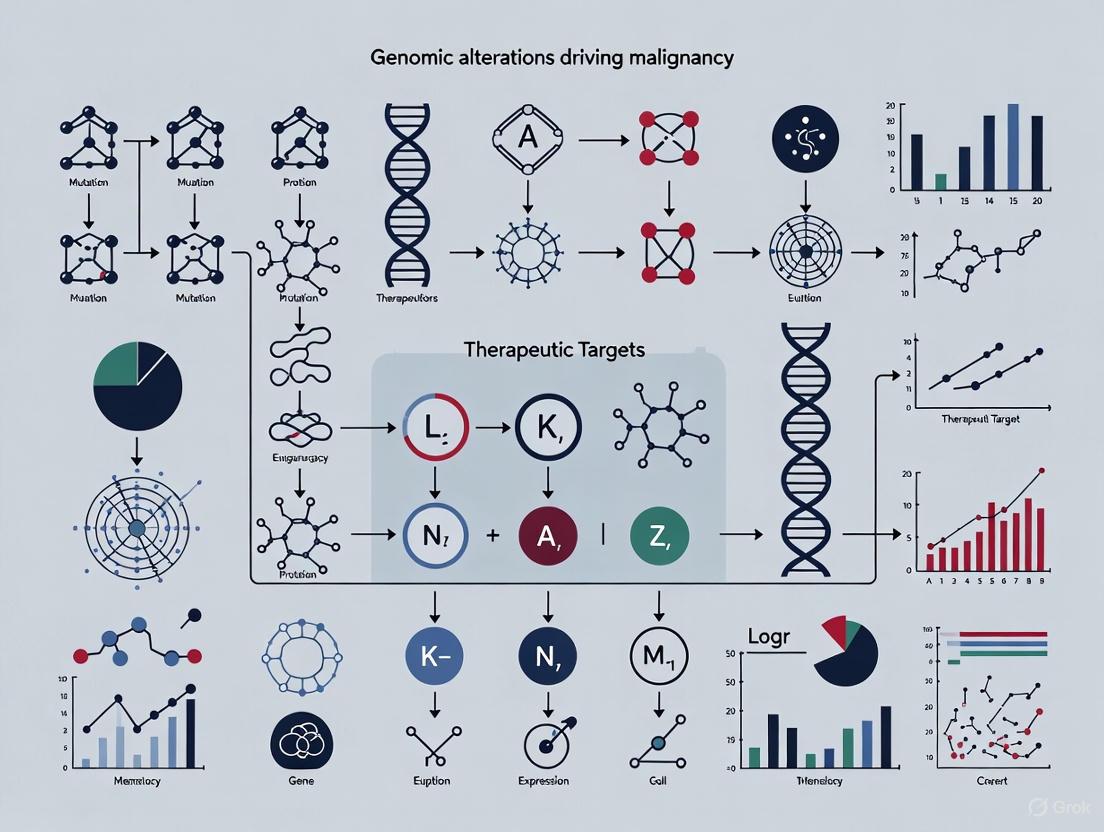

This comprehensive review explores the rapidly evolving landscape of genomic alterations driving malignancy and their translation into targeted therapeutic strategies.

Actionable Genomic Alterations in Cancer: From Discovery to Targeted Therapies and Clinical Validation

Abstract

This comprehensive review explores the rapidly evolving landscape of genomic alterations driving malignancy and their translation into targeted therapeutic strategies. Covering foundational concepts of oncogenic drivers across diverse malignancies including NSCLC, ALL, thyroid, and breast cancers, we examine methodological approaches from next-generation sequencing to circulating tumor DNA analysis. The article addresses troubleshooting therapeutic resistance and optimizing combination therapies, while validating approaches through comparative genomic studies and clinical trial outcomes. This resource provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with current insights into precision oncology frameworks, emerging biomarkers, and future directions for targeted cancer therapy development.

The Genomic Landscape of Malignancy: Key Alterations and Pathways Driving Oncogenesis

Cancer pathogenesis is driven by genomic alterations that dysregulate core intracellular signaling pathways, leading to uncontrolled cell proliferation, survival, and metabolic reprogramming. The MAPK, PI3K-AKT-mTOR, and p53 pathways represent three critical signaling networks frequently mutated in human malignancies. This review provides a comprehensive analysis of their molecular architectures, oncogenic mechanisms, and therapeutic targeting. The MAPK pathway, particularly through RAS and BRAF mutations, drives proliferation in colorectal and lung cancers. The PI3K-AKT-mTOR axis, one of the most frequently activated pathways in cancer, integrates growth signals to regulate metabolism, survival, and treatment resistance. Meanwhile, p53, known as the "guardian of the genome," is inactivated in approximately half of all cancers, removing a critical barrier to tumor development. We examine the genomic alterations underlying pathway dysregulation, summarize current and emerging therapeutic strategies, and present standardized experimental methodologies for investigating these pathways. The continued elucidation of these core signaling networks remains essential for advancing precision oncology and developing more effective cancer treatments.

Cancer development depends fundamentally on genomic mutations that drive abnormal proliferation and immune evasion [1]. The core signaling pathways reviewed here—MAPK, PI3K-AKT-mTOR, and p53—represent central hubs where genetic alterations converge to enable malignant transformation, tumor progression, and therapeutic resistance. The PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling axis is a pivotal regulator of key cellular functions, including proliferation, metabolism, survival, and immune modulation, with dysregulation driving malignant transformation and tumor progression [1] [2]. Similarly, the MAPK pathway, particularly through RAS oncogene mutations present in about half of all colorectal cancer (CRC) cases, creates persistent signaling activation that promotes proliferation and treatment resistance [3]. Meanwhile, mutations in the TP53 gene occur in almost half of all human cancers, with mutation patterns that are often cancer-specific and confer oncogenic potential distinct from wild-type p53 [4] [5]. The interplay between these pathways creates complex regulatory networks that pose both challenges and opportunities for therapeutic intervention.

The MAPK Signaling Pathway

Molecular Architecture and Oncogenic Activation

The Mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathway plays a crucial role in regulating cellular proliferation and differentiation, with dysregulation closely linked to cancer etiology, progression, and malignant behavior [3]. This cascade is particularly significant in colorectal cancer, where over 60% of cases involve MAPK-activated signal pathways, particularly driven by RAS oncogene mutations [3]. The RAS protein family includes HRAS, NRAS, and two KRAS variants (4A and 4B), with KRAS mutations being the most prevalent, accounting for 40–50% of RAS-mutant CRCs [3]. Beyond RAS, BRAF mutations, particularly the BRAF V600E variant, also contribute to MAPK pathway activation via downstream MEK and ERK signaling [3].

RAS and BRAF mutations are generally recognized as negative prognostic factors. Patients with these mutations often show resistance to anti-EGFR therapies, leaving them with limited treatment options and generally poor outcomes [3]. Consequently, cancers with these mutations have historically been challenging to treat and are sometimes referred to as 'undruggable' [3]. These mutations have profound effects on tumor development: KRAS mutations can accelerate tumor progression and cell proliferation, typically emerging early in the disease course, while NRAS mutations may hinder the cell's ability to undergo stress-induced death [3].

Genomic Alterations and Therapeutic Targeting

The high prevalence of MAPK pathway mutations has driven the development of targeted therapies, particularly for colorectal cancer. KRAS mutations are present in 25–30% of lung adenocarcinomas and have historically been considered untreatable with drugs due to the lack of suitable binding pockets for therapeutic intervention [6]. However, recent breakthroughs, particularly the development of KRAS G12C inhibitors such as sotorasib and adagrasib, have yielded promising clinical results, opening new therapeutic avenues for this patient population [6].

Table 1: Prevalence of MAPK Pathway Alterations in Selected Cancers

| Cancer Type | Common Mutations | Prevalence | Therapeutic Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Colorectal Cancer | KRAS mutations | 40-50% of RAS-mutant CRCs [3] | Resistance to anti-EGFR therapies [3] |

| Lung Adenocarcinoma | KRAS mutations | 25-30% [6] | KRAS G12C inhibitors (sotorasib, adagrasib) [6] |

| Colorectal Cancer | BRAF V600E | ~10% of cases [3] | Contributes to MAPK activation via MEK and ERK [3] |

| NSCLC | BRAF mutations | ~10% of cases [3] | BRAF inhibitors in combination with MEK inhibitors |

Mendelian randomization protein quantitative trait loci (pQTL) analysis has identified several plasma proteins associated with increased risk of MAPK-activated CRCs, including MHC class I polypeptide-related sequence B (MICB), complement C4A, C4B, and interleukin-21 (IL-21) [3]. These findings highlight the potential for utilizing plasma proteins as therapeutic targets and diagnostic markers to advance cancer treatment, indicating promising results for more effective interventions [3].

Experimental Protocols for MAPK Pathway Investigation

Protocol 1: Two-Sample Mendelian Randomization pQTL Analysis

- Objective: To investigate causal associations between plasma proteins and MAPK-activated cancers.

- Methodology:

- Instrumental Variable Selection: Identify independent single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with plasma protein levels from genome-wide association studies (GWAS). Apply linkage disequilibrium clumping (R² < 0.01 within 1,000 kb) to select strong instrumental variables [3].

- Genetic Association Data: Obtain genetic association estimates for MAPK-activated cancers from large-scale cancer consortia.

- MR Analysis: Perform two-sample MR using inverse-variance weighted (IVW) method as primary analysis, with supplementary methods (MR-Egger, weighted median) to assess robustness [3].

- Sensitivity Analyses: Conduct MR-Egger intercept test for directional pleiotropy, Cochrane's Q-test for heterogeneity, and MR-PRESSO to identify and remove outlier SNPs [3].

- Applications: Causal inference of plasma proteins in MAPK-activated colorectal cancer risk.

Protocol 2: MAPK Signaling Assay in Cell Lines

- Objective: To evaluate MAPK pathway activation and inhibitor responses in cancer cell lines.

- Methodology:

- Cell Culture: Maintain cancer cell lines with known RAS/BRAF mutation status in appropriate media.

- Treatment: Expose cells to MAPK pathway inhibitors (BRAF inhibitors, MEK inhibitors) at varying concentrations.

- Protein Extraction and Western Blotting: Harvest cells, extract proteins, and perform Western blotting for phosphorylated ERK (p-ERK), total ERK, and other pathway components.

- Proliferation Assays: Assess cell viability using MTT or CellTiter-Glo assays post-inhibitor treatment.

- RNA Sequencing: Conduct transcriptomic profiling to identify gene expression changes associated with drug resistance [3].

- Applications: Evaluation of MAPK inhibitor efficacy and resistance mechanisms.

The PI3K-AKT-mTOR Signaling Axis

Pathway Components and Genetic Alterations

The PI3K/AKT/mTOR (PAM) signaling pathway is a highly conserved signal transduction network in eukaryotic cells that promotes cell survival, cell growth, and cell cycle progression [7]. This axis is the most frequently activated signaling pathway in human cancer, with aberrations occurring in approximately 50% of tumors, and is often implicated in resistance to anticancer therapies [7]. The human genome encodes three classes of PI3K p110 isoforms, including p110α (encoded by PIK3CA) and p110β (PIK3CB), which demonstrate expression in various cell types, and p110δ (PIK3CD), with specific expression in immune cells [1]. Among these, class IA PI3Ks, and specifically the p110α isoform, demonstrate significant function in human cancers [1].

The mTOR protein is a conserved serine/threonine kinase with significant function in regulating growth and metabolism, existing in two complexes: mTORC1 (rapamycin-sensitive) and mTORC2 [1]. Positive regulators of mTOR include growth factor receptors, while negative regulators include PTEN, TSC1/2, and LKB1 [1]. Dysregulation of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR axis has been observed in human cancers, increasing proliferation and metastasis [1]. PI3K/PIP3 signal termination is mainly attained by tumor suppressor PTEN, which dephosphorylates PIP3, thereby switching it back to PIP2; thus, PTEN acts as an essential negative regulator of the PAM pathway, whereas loss of PTEN results in sustained oncogenic signaling [7].

Oncogenic Mechanisms and Cancer Hallmarks

The PI3K/AKT/mTOR axis governs multiple oncogenic mechanisms in cancer, including regulation of epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), autophagy, apoptosis, glycolysis, ferroptosis, and lipid metabolism [1] [2]. The pathway contributes significantly to therapy resistance, immune evasion, and metastasis [1]. Overactivity of the PAM pathway promotes EMT and metastasis through its remarkable impact on cell migration [7]. The pathway also demonstrates a dual function in regulating apoptosis, autophagy, and EMT, providing novel therapeutic targets [1].

The PI3K/AKT/mTOR axis is crucial in cancer progression, regulating cell growth, survival, and metabolism [1]. It is often hyperactivated through mutations or loss of tumor suppressors such as PTEN, which promotes cancer cell proliferation and survival by inhibiting apoptosis and activating mTOR, thereby driving protein synthesis and suppressing autophagy [1]. The axis also contributes to therapy resistance, immune evasion, and metastasis [1].

Table 2: PI3K/AKT/mTOR Pathway Genetic Alterations in Human Cancers

| Genetic Alteration | Affected Component | Cancer Types | Functional Consequences |

|---|---|---|---|

| PIK3CA mutations/amplifications | Catalytic subunit p110α of PI3K | Breast, colorectal, lung, gastric, prostate, cervical cancers [7] | Enhanced lipid kinase activity, sustained AKT activation [7] |

| PTEN loss-of-function | Lipid phosphatase | Breast cancer, gastric cancer, glioblastoma [7] | PIP3 accumulation, constitutive PI3K pathway activation [7] |

| AKT amplification/gain-of-function | AKT kinase | Various cancers [7] | Enhanced survival signaling, treatment resistance [7] |

| PIK3R1 mutations | Regulatory subunit p85α of PI3K | Glioblastoma, ovarian cancer, renal cancer [7] | Altered regulatory function, pathway dysregulation |

Experimental Analysis of PI3K/AKT/mTOR Signaling

Protocol 1: Assessment of PI3K Pathway Activation Status

- Objective: To evaluate PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway activity in tumor samples or cell lines.

- Methodology:

- Immunohistochemistry (IHC): Perform IHC staining for phosphorylated AKT (Ser473), phosphorylated S6 ribosomal protein (Ser235/236), and PTEN expression on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections [7].

- Western Blot Analysis: Extract proteins from fresh frozen tissues or cell lines. Probe with antibodies against total and phosphorylated forms of PI3K pathway components (p-AKT, p-S6K, p-4E-BP1, p-PDK1) [7].

- Genomic DNA Sequencing: Sequence key pathway genes (PIK3CA, PIK3R1, PTEN, AKT1) using Sanger or next-generation sequencing to identify hotspot mutations [7].

- Functional Assays: Assess pathway dependency through inhibitor sensitivity assays using PI3K, AKT, or mTOR inhibitors [1].

- Applications: Comprehensive molecular profiling of PAM pathway status for therapeutic decision-making.

Protocol 2: Preclinical Evaluation of PI3K Pathway Inhibitors

- Objective: To evaluate efficacy and mechanisms of action of PI3K/AKT/mTOR inhibitors.

- Methodology:

- In Vitro Screening: Test inhibitors across cancer cell line panels with varying PAM pathway alteration status. Assess IC50 values using viability assays [7].

- Pathway Modulation Studies: Treat sensitive and resistant cell lines with inhibitors and analyze pathway phosphorylation changes by Western blot [7].

- Combination Studies: Evaluate synergistic interactions with standard chemotherapy, targeted agents, or immunotherapy [1] [7].

- In Vivo Validation: Administer inhibitors to patient-derived xenograft (PDX) models with defined PAM pathway alterations. Monitor tumor growth and perform pharmacodynamic analysis of pathway inhibition [7].

- Applications: Preclinical development of PI3K pathway-targeted therapies.

The p53 Tumor Suppressor Pathway

Molecular Functions and Regulatory Networks

Tumor protein p53 (TP53) has long been recognized as one of the most important genes in regulating cell death and has been called the "cellular gatekeeper" or "the guardian of the genome" [4]. p53 is a tumor suppressor gene that, when functioning normally, recognizes abnormal DNA, abnormal tubulin, or other abnormalities which could result in cancer, initiating a cascade of events that results in cell death [4]. As a transcription factor, wildtype p53 controls cell death in a highly redundant fashion, regulating five forms of cell death: (1) apoptosis, (2) ferroptosis, (3) necroptosis mediated by TNF, (4) necroptosis mediated by FAS ligand, and (5) senescence with an associated memory immune response [4].

Wildtype p53 in a healthy cell is expressed at very low levels to prevent premature death, with expression controlled via a negative feedback loop between WT p53 and Mouse double minute two homolog (MDM2), also known as E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase [4]. The Mdm2 gene is a transcriptional target of the p53 protein and its product ubiquitinates p53, rendering it susceptible to degradation by proteosomes, thus maintaining normal homeostasis [4]. After cells with native p53 are exposed to extracellular or intracellular stressors, the protein accumulates and activates target genes such as p21 (promoting cell cycle arrest) and pro-apoptotic proteins Bax, PUMA, and Noxa, which collectively determine the cell's fate: senescence or regulated death [4].

Mutational Spectrum and Oncogenic Consequences

Mutations in p53 occur in almost half of all human cancers, with mutation patterns that are cancer-specific and associated genomic changes that grant mutant p53 with oncogenic potential unique from that of wild-type p53 [4] [5]. The DNA-binding core domain of the p53 protein is the most frequently mutated in cancer cells, with hotspot mutations studied via NMR and X-ray crystallography due to their oncologic potential [4]. Common polymorphisms include the structural mutants G245S and R249S, with Loops L2 and L3 being the most commonly structurally altered regions, which are hypothesized to disrupt the DNA-binding surface [4].

While the tumor suppressor protein is often inactivated in cancer cells to allow for increased proliferation, wildtype p53 is retained in certain cancers where its pro-survival effects become the dominant driving force to cellular longevity [4]. Specifically, p53 in these cells directly activates genes with anti-apoptotic activity and promotes maintenance of low levels of reactive oxygen species to prevent cell death [4]. For example, in a subtype of glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) known as primary GBM, 70% of glioma cells express wildtype p53 and these cells have been observed to have a selective impairment of the apoptotic functions of WT p53, while still being able to regulate p53 control over DNA repair and control of cell cycle [4].

Table 3: p53 Pathway Alterations in Human Cancers and Therapeutic Approaches

| Alteration Type | Mechanism | Prevalence | Therapeutic Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

| TP53 missense mutations | DNA-binding domain mutations, structural/contact residues | ~50% of all human cancers [4] [5] | Structural reactivators, synthetic lethal agents [4] |

| MDM2/MDM4 amplification | Enhanced p53 degradation | Various cancers, including sarcomas | MDM2 inhibitors, viral approaches [4] |

| Wildtype p53 retention with impaired apoptosis | Selective impairment of apoptotic functions | Primary glioblastoma multiforme (70% of cases) [4] | Epigenetic modifiers, immune activating vaccines [4] |

| p53 pathway epigenetic silencing | Regulatory component dysregulation | Multiple cancer types | Bypassing p53 entirely [4] [5] |

Experimental Methods for p53 Pathway Investigation

Protocol 1: Comprehensive p53 Mutational Analysis

- Objective: To characterize TP53 mutation status and functional consequences in cancer models.

- Methodology:

- DNA Sequencing: Sequence TP53 exons 2-11 in tumor DNA using Sanger sequencing or next-generation sequencing panels. Focus on hotspot codons in the DNA-binding domain [4].

- Immunohistochemistry: Stain for p53 protein expression; missense mutations typically show strong nuclear staining, while truncating mutations show complete absence [4].

- Functional Assays: Transfer mutant p53 constructs into p53-null cells and assess transcriptional activity on reporter constructs containing p53 response elements [4].

- Drug Sensitivity Screening: Test chemotherapeutic agents and targeted compounds in isogenic cell lines differing in p53 status to identify synthetic lethal interactions [4].

- Applications: Determine p53 functional status and identify mutation-specific therapeutic vulnerabilities.

Protocol 2: Assessment of p53-Dependent Cell Death Pathways

- Objective: To evaluate which cell death pathways remain functional in p53-mutant cancers.

- Methodology:

- Apoptosis Assays: Treat cells with DNA-damaging agents and measure apoptosis by Annexin V/propidium iodide staining and caspase-3/7 activation assays [4].

- Ferroptosis Induction: Expose cells to ferroptosis inducers (e.g., erastin, RSL3) with or without iron chelators or antioxidants. Measure lipid peroxidation via C11-BODIPY assay [4].

- Senescence-Associated β-galactosidase Staining: Detect senescent cells using SA-β-gal staining at pH 6.0 following stress induction [4].

- Transcriptional Profiling: Perform RNA sequencing to identify p53 target gene expression patterns after stress induction [4].

- Applications: Identify functional cell death pathways that can be therapeutically exploited in p53-mutant tumors.

Cross-Pathway Interactions and Therapeutic Integration

The core signaling pathways in cancer—MAPK, PI3K-AKT-mTOR, and p53—do not function in isolation but engage in extensive cross-talk that influences tumor behavior and therapeutic responses. The PI3K/AKT/mTOR axis demonstrates significant interaction with multiple other signaling pathways, and growth factor signaling to transcription factors in this axis is highly regulated by multiple cross-interactions with several other signaling pathways [7]. Dysregulation of these interconnected networks can predispose to cancer development and drive resistance to anticancer therapies [7]. The Targeted Agent and Profiling Utilization (TAPUR) Study, a phase II basket trial, has demonstrated the importance of understanding the prevalence of targetable genomic alterations across diverse populations, revealing differences in alteration frequencies across racial and ethnic groups that may inform strategic treatment plans considering patient demographics in addition to tumor characteristics [8].

Emerging therapeutic strategies increasingly focus on targeting multiple pathways simultaneously or sequentially to overcome resistance mechanisms. For example, in lung cancer, the PI3K/AKT/mTOR axis serves a central role in tumor growth and survival, with activation frequently driven by mutations or amplifications in upstream regulators such as EGFR and KRAS [6]. Dysregulation of this pathway contributes to resistance against both chemotherapy and targeted therapies, positioning it as a key focus of ongoing research [6]. Current preclinical and clinical investigations are assessing inhibitors targeting components of this pathway, including PI3K, AKT, and mTOR, both as monotherapies and in combination regimens, with the aim of overcoming therapeutic resistance and improving patient outcomes [6].

Visualization of Pathway Architecture and Experimental Approaches

PI3K-AKT-mTOR Signaling Pathway

Diagram Title: PI3K-AKT-mTOR Pathway with Key Cancer Alterations

Experimental Workflow for Pathway Analysis

Diagram Title: Experimental Workflow for Pathway Analysis

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Core Pathway Investigation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Applications | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pathway Inhibitors | PI3K inhibitors (alpelisib), AKT inhibitors (ipatasertib), mTOR inhibitors (everolimus), MEK inhibitors (trametinib), BRAF inhibitors (dabrafenib) | Functional validation of pathway dependencies, combination therapy studies | Assess pathway inhibition via phosphorylation status of direct substrates [1] [7] |

| Antibodies for Immunoblotting | Phospho-AKT (Ser473), total AKT, phospho-S6 (Ser235/236), phospho-ERK1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204), p53, MDM2 | Protein expression and activation status assessment | Validate antibody specificity using knockout/knockdown controls [4] [7] |

| CRISPR/Cas9 Systems | sgRNAs targeting PIK3CA, PTEN, TP53, KRAS, BRAF | Isogenic cell line generation, gene function validation | Use dual-sgRNA approach for large deletions; include proper controls for off-target effects [9] |

| Cell Viability Assays | MTT, CellTiter-Glo, colony formation assays | Compound screening, proliferation measurements | Use multiple assays for confirmation; account for metabolic changes in interpretation [3] [7] |

| Apoptosis/Ferroptosis Detection | Annexin V/propidium iodide, caspase-3/7 activation, C11-BODIPY lipid peroxidation sensor | Cell death mechanism characterization | Include appropriate positive controls (e.g., erastin for ferroptosis) [4] |

| NGS Panels | Targeted sequencing for cancer-associated genes (PIK3CA, PTEN, TP53, KRAS, BRAF) | Genomic alteration identification | Include matched normal DNA for somatic mutation calling; validate findings with orthogonal methods [8] [9] |

The MAPK, PI3K-AKT-mTOR, and p53 signaling pathways represent central regulatory networks whose dysregulation drives cancer pathogenesis through distinct yet interconnected mechanisms. The PI3K/AKT/mTOR axis stands as one of the most frequently activated pathways in human cancer, integrating growth signals to control cell survival, metabolism, and proliferation. MAPK pathway activation, particularly through RAS and BRAF mutations, promotes uncontrolled proliferation and treatment resistance in numerous malignancies. Meanwhile, p53 pathway inactivation removes a critical cellular defense mechanism, enabling tumor development and progression. The continued elucidation of the genomic alterations affecting these pathways, their functional consequences, and their therapeutic targeting remains essential for advancing precision oncology. Emerging technologies including CRISPR-based gene editing, advanced genomic profiling, and artificial intelligence are refining our understanding of these pathways and enabling more targeted therapeutic approaches. Future research should focus on understanding pathway cross-talk, context-dependent functions, and resistance mechanisms to improve patient outcomes across diverse cancer types and populations.

Prevalent Actionable Genomic Alterations Across Major Cancer Types

Comprehensive Genomic Profiling (CGP) has fundamentally transformed cancer therapy selection by enabling a tumor-agnostic approach that prioritizes molecular alterations over tissue of origin. The identification of prevalent actionable genomic alterations represents a cornerstone of modern precision oncology, providing the scientific foundation for molecularly-guided therapies that improve patient outcomes [10] [11]. Advances in next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies have facilitated high-throughput interrogation of cancer genomes, simultaneously driving an increase in actionable therapeutic targets and the regulatory approval of multiple tumor-agnostic treatments [10]. This technical guide synthesizes current evidence on the prevalence and clinical actionability of genomic alterations across major cancer types, providing researchers and drug development professionals with essential data structured to inform both research protocols and therapeutic development strategies.

The clinical utility of molecular profiling is demonstrated by real-world evidence from diverse populations. A recent 2025 study of 1,166 Asian patients with 29 different cancer types found that 62.3% of samples harbored actionable biomarkers that could potentially guide therapy selection [10]. This high actionability rate underscores the significance of CGP in facilitating precision medicine across diverse ethnic populations and cancer types, with particular importance for understanding genomic alterations that drive malignancy and present viable therapeutic targets.

Actionable Genomic Alterations: Prevalence and Distribution Across Major Cancers

Comprehensive Alteration Landscape

The genomic mutational landscape across cancer types reveals distinct patterns of alteration prevalence and actionability. Analysis of 1,166 patient samples identified 1,291 somatic variants (4.7% of all variants) as potentially targetable by regulatory-approved therapies [10]. The likelihood of identifying at least one actionable molecular alteration varies significantly by cancer type, being highest in central nervous system (CNS) tumors (83.6%), followed by lung cancer (81.2%), and breast cancer (79.0%) [10]. These findings highlight the differential potential for precision medicine approaches across cancer types.

Table 1: Prevalence of Actionable Genomic Alterations Across Major Cancer Types

| Cancer Type | Actionable Alteration Prevalence (%) | Most Frequent Alterations | Tumor-Agnostic Biomarker Prevalence (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CNS Tumors | 83.6 | BRAF V600E | 8.4 |

| Lung Cancer | 81.2 | EGFR, KRAS, BRAF V600E | 16.8 |

| Breast Cancer | 79.0 | PIK3CA, ERBB2 amplification, BRCA1/2 | 15.0 (ERBB2 amp) |

| Colorectal Cancer | 62.3* | KRAS, BRAF V600E, MSI-H | 12.8* |

| Ovarian Cancer | 42.2 (HRD) | HRD, BRCA1/2, ERBB2 amplification | 8.9 (ERBB2 amp) |

| Endometrial Cancer | 11.8 (MSI-H) | MSI-H, ERBB2 amplification, TMB-H | 11.8 (ERBB2 amp) |

| Prostate Cancer | 11.1* | BRCA1/2, MSI-H, HRD | 22 (BRCA1/2) |

| Pancreatic Cancer | 8.7* | KRAS, HRD, NTRK fusions | 8.7* |

| Gastric Cancer | 4.7 (MSI-H) | MSI-H, ERBB2 amplification, HRD | 4.7 (MSI-H) |

| Melanoma | 22.7 | BRAF V600E, TMB-H | 22.7 |

*Overall representation in cohort; specific actionability data not provided in source material [10]

Established Tumor-Agnostic Biomarkers

Tumor-agnostic biomarkers represent particularly valuable targets for therapeutic development as they transcend histology-based classification systems. Among 29 cancer types studied, at least one tumor-agnostic biomarker was detected in 26 cancer types (89.7%), affecting 98 samples (8.4%) [10]. These biomarkers include microsatellite instability-high (MSI-H) status, high tumor mutational burden (TMB-H), NTRK fusions, RET fusions, and BRAF V600E mutations [10].

- MSI-H Status: A total of 16 cases with MSI-high status were observed, with the highest proportions in endometrial (5.9%), gastric (4.7%), and cancer of unknown primary (4%) tumors [10].

- TMB-H Status: 6.6% of samples (77/1166) were TMB-high, with the highest proportions in lung (15.4%), endometrial (11.8%), and esophageal (11.1%) cancers [10].

- Gene Fusions and Mutations: RET fusions were detected exclusively in lung cancers, while NTRK fusions were identified in pancreatic, gastric, and colorectal cancers. BRAF V600E mutations were found across multiple cancer types, including colorectal cancer, melanoma, and thyroid cancer [10].

Table 2: Established and Emerging Tumor-Agnostic Biomarkers

| Biomarker Category | Specific Alterations | Overall Prevalence (%) | Most Affected Cancer Types |

|---|---|---|---|

| Established Tumor-Agnostic | MSI-H | 1.4 | Endometrial, Gastric, Unknown Primary |

| TMB-H | 6.6 | Lung, Endometrial, Esophageal | |

| BRAF V600E | 1.2 | Colorectal, Melanoma, Thyroid | |

| NTRK Fusions | 0.3 | Pancreatic, Gastric, Colorectal | |

| RET Fusions | 0.2 | Lung | |

| Emerging Tumor-Agnostic | HRD | 34.9 | Breast, Colorectal, Lung, Ovarian, Gastric |

| ERBB2 Amplification | 3.6 | Breast, Endometrial, Ovarian | |

| FGFR Alterations | Not specified | Various | |

| NRG1 Fusions | Not specified | Various |

Homologous Recombination Deficiency and ERBB2 Amplification

Beyond the established tumor-agnostic biomarkers, several emerging targets show significant promise for therapeutic development:

- Homologous Recombination Deficiency (HRD): This emerging tumor-agnostic biomarker was observed in 34.9% of samples (407/1166) and was present in approximately half of breast (50%), colorectal (49.0%), lung (44.2%), ovarian (42.2%), and gastric (39.5%) tumors [10]. HRD-positive tumors exhibited significantly higher TMB compared to HRD-negative tumors (median TMB 5.58 vs. 5.15, respectively), suggesting a potential synergistic relationship between these biomarkers [10].

- ERBB2 Amplification: This alteration was identified in 3.6% of samples (42/1166), with the highest frequencies in breast (15.0%), endometrial (11.8%), and ovarian (8.9%) cancers [10]. The distribution across multiple cancer types positions ERBB2 amplification as a promising candidate for tumor-agnostic drug development.

Methodologies for Comprehensive Genomic Profiling

Experimental Protocols for Genomic Alteration Detection

Comprehensive genomic profiling requires standardized methodologies to ensure consistent and reproducible results. The following protocol outlines the key steps for DNA and RNA sequencing from tumor tissues:

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Comprehensive Genomic Profiling

| Reagent/Technology | Function | Application in Genomic Profiling |

|---|---|---|

| UNITED DNA/RNA Multigene Panel [10] | Target enrichment for sequencing | Simultaneous detection of SNVs, indels, CNVs, fusions, MSI, and TMB |

| Northstar Select Liquid Biopsy Assay [12] | Plasma-based ctDNA analysis | Detection of SNVs/Indels, CNVs, fusions, and MSI status in liquid biopsy |

| Digital Droplet PCR (ddPCR) [12] | Absolute quantification of nucleic acids | Analytical validation with 95% Limit of Detection of 0.15% VAF for SNV/Indels |

| Next-Generation Sequencing Platforms | High-throughput DNA/RNA sequencing | Multiplexed sequencing of targeted gene panels |

| Circulating Tumor DNA (ctDNA) Collection Tubes | Blood sample preservation | Stabilization of cell-free DNA for liquid biopsy analysis |

Figure 1: Comprehensive Genomic Profiling Workflow Integrating Tissue and Liquid Biopsy Approaches

Analytical Validation of Genomic Tests

Robust analytical validation is essential for implementing genomic profiling in both research and clinical settings. Recent advancements in liquid biopsy technologies have addressed previous limitations in detection sensitivity:

- Northstar Select Liquid Biopsy Assay: This plasma-based CGP test demonstrates a 95% limit of detection at 0.15% variant allele frequency (VAF) for single nucleotide variants and insertions/deletions, with sensitive detection of copy number variations (2.11 copies for amplifications, 1.80 copies for losses) and gene fusions (0.30% VAF) [12].

- Performance Comparison: In head-to-head comparisons with existing commercial CGP assays, this enhanced sensitivity resulted in the identification of 51% more pathogenic SNVs/indels and 109% more CNVs, significantly reducing null reports with no actionable findings [12].

- Clinical Implications: The majority (91%) of additional clinically actionable variants detected by this high-sensitivity approach were found below 0.5% VAF, highlighting the importance of detection sensitivity for comprehensive alteration identification, particularly in low-shedding tumors [12].

Clinical Actionability Assessment Frameworks

ESMO Scale for Clinical Actionability of Molecular Targets (ESCAT)

The European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) has developed the ESCAT classification system to provide a standardized framework for categorizing genomic alterations based on evidence supporting their value as clinical targets [13]. This six-tier system enables consistent prioritization of molecular alterations for therapeutic targeting:

- Tier I: Targets ready for implementation in routine clinical decisions

- Tier II: Investigational targets that likely define a patient population that benefits from a targeted drug but additional data are needed

- Tier III: Clinical benefit previously demonstrated in other tumour types or for similar molecular targets

- Tier IV: Preclinical evidence of actionability

- Tier V: Evidence supporting co-targeting approaches

- Tier X: Lack of evidence for actionability [13]

Application of this classification system in real-world cohorts demonstrates its clinical utility. In a study of 1,166 patients, 12.7% of samples (148/1166) harbored Tier I alterations, including PIK3CA mutations in breast cancer, EGFR exon 19 mutations in non-small cell lung cancer, and BRCA1/2 alterations in prostate cancer [10]. An additional 6.0% of samples (70/1166) contained Tier II alterations, including BRCA1/2 somatic mutations in breast cancer and ERBB2 mutations [10].

Clinical Outcomes Based on Actionability Tiers

Evidence increasingly supports the clinical utility of actionability frameworks for predicting therapeutic outcomes. A study of 1,226 patients presented at molecular tumor boards found that 49% (595/1226) had actionable genomic alterations, with 8% (101/1226) ultimately receiving matched therapy [14]. Critically, patients treated with matched therapies based on ESCAT Tiers I/II demonstrated significantly longer progression-free survival and overall survival compared to those treated based on Tiers III/IV alterations [14].

Figure 2: ESCAT Framework for Clinical Actionability of Genomic Alterations

Emerging Research Directions and Technologies

Advancing Detection Technologies

The field of genomic alteration detection continues to evolve with several promising technological developments:

- Circulating Tumor DNA (ctDNA) Monitoring: Research increasingly supports the utility of ctDNA for monitoring treatment response and guiding dose optimization in early-phase clinical trials [15]. While showing promise as a short-term biomarker, experts emphasize that ctDNA clearance must correlate with long-term outcomes such as event-free and overall survival to serve as a validated endpoint [15].

- Spatial Transcriptomics and Single-Cell Sequencing: These technologies are advancing understanding of the tumor microenvironment, potentially enabling identification of novel predictive biomarkers for immunotherapy beyond current standards (PD-L1, MSI status, TMB) [15].

- Artificial Intelligence in Digital Pathology: AI and machine learning algorithms applied to hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) slides show potential for imputing transcriptomic profiles and identifying subtle patterns predictive of treatment response or resistance [15].

Novel Therapeutic Approaches

The expanding knowledge of actionable genomic alterations is driving innovation in therapeutic development:

- Next-Generation KRAS Inhibitors: Research is advancing beyond first-generation KRASG12C inhibitors to second-generation variants and early evaluation of KRASG12D, KRASG12V, pan-KRAS, and pan-RAS inhibitors [15]. These developments are particularly relevant for pancreatic cancer, where KRAS mutations occur in over 90% of patients [15].

- Antibody-Drug Conjugates (ADCs): Ongoing research focuses on identifying biomarkers for ADC selection beyond immunohistochemistry and developing novel ADC designs with improved therapeutic indices through optimized linkers and payloads [15].

- Cancer Vaccines: Clinical trials are exploring both personalized neoantigen vaccines and off-the-shelf shared antigen vaccines across cancers with varying mutational burdens [15].

The comprehensive characterization of prevalent actionable genomic alterations across major cancer types provides a critical foundation for advancing precision oncology. Current evidence demonstrates that over 60% of advanced cancers harbor potentially actionable alterations, with established tumor-agnostic biomarkers identified in 8.4% of cases and emerging targets like homologous recombination deficiency present in 34.9% [10]. Standardized frameworks such as the ESCAT classification system enable consistent prioritization of these alterations for therapeutic development, with demonstrated improvements in patient outcomes when treatments are matched to high-evidence targets [14].

Future progress will depend on continued technological innovations in detection sensitivity, particularly for low-frequency alterations and low-shedding tumors, alongside the development of next-generation therapeutic approaches that target previously "undruggable" alterations. The integration of multi-modal biomarkers beyond genomics—including transcriptomics, proteomics, and digital pathology—holds promise for advancing beyond current stratified medicine approaches toward truly personalized cancer therapy. For researchers and drug development professionals, these findings underscore the importance of comprehensive genomic profiling and evidence-based target prioritization in developing the next generation of cancer therapeutics.

Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) represents approximately 85% of all lung cancer diagnoses and constitutes a leading cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide [16] [17]. The treatment landscape for advanced NSCLC has been revolutionized by the discovery of oncogenic driver mutations and the development of molecularly targeted therapies. These driver alterations, which include mutations in EGFR and KRAS, as well as rearrangements in ALK and ROS1, promote tumor growth and survival through the constitutive activation of critical signaling pathways [18] [19]. Comprehensive molecular profiling has become essential for guiding treatment decisions in precision oncology, with approximately 60% of NSCLC patients now harboring identifiable driver mutations [16]. This in-depth technical guide examines the molecular biology, epidemiology, detection methodologies, and therapeutic targeting of five core oncogenic drivers in NSCLC: EGFR, ALK, ROS1, MET, and KRAS.

Molecular Epidemiology and Prevalence

The distribution of oncogenic drivers in NSCLC varies significantly according to geographic region, ethnicity, smoking history, and histological subtype. Table 1 summarizes the prevalence of key driver mutations in NSCLC populations globally and in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region specifically.

Table 1: Prevalence of Oncogenic Drivers in NSCLC

| Driver Alteration | Global Prevalence (%) | MENA Region Prevalence (%) (95% CI) | Associated Patient Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| EGFR | 10-16 (Western) [18]; 40-60 (Asian) [17] | 24.0 (22.05-25.41) [16] | Non-smokers, females, Asian ethnicity, adenocarcinoma [19] [17] |

| ALK | 3-7 [18] | 7.9 (6.69-9.03) [16] | Young age, light/never-smokers, adenocarcinoma [19] [20] |

| KRAS | 22-33 [18]; ~25-30 (adenocarcinoma) [18] | 19.7 (15.29-24.07) [16] | Smoking history, Western populations [19] [17] |

| ROS1 | 1-2 [18] | 2.2 (0.77-3.57) [16] | Never-smokers, adenocarcinoma [20] |

| MET | 2-5 [18] | 4.7 (2.29-7.07) [16] | Variable, exon 14 skipping mutations [20] |

The KRAS G12C subtype represents a particularly important actionable mutation, found in approximately 13% of patients with non-squamous NSCLC [21]. These driver mutations are generally mutually exclusive, though rare cases of co-occurring alterations have been reported, often involving EGFR with other drivers [22] [23].

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Mechanisms

Oncogenic drivers in NSCLC constitutively activate key intracellular signaling cascades—primarily the MAPK and PI3K/AKT pathways—that regulate cell growth, proliferation, and survival [18] [19]. The following diagram illustrates the core signaling pathways and their therapeutic targeting.

EGFR Signaling and Oncogenic Activation

Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR) is a transmembrane receptor tyrosine kinase that modulates crucial cellular processes including proliferation, growth, and apoptosis inhibition through the MAPK, PI3K/AKT, and JAK/STAT pathways [19]. Oncogenic activation primarily occurs through mutations in the tyrosine kinase domain, most commonly exon 19 deletions or the L858R point mutation in exon 21, which result in constitutive kinase activity independent of ligand binding [19]. These mutations reduce the receptor's affinity for ATP while increasing sensitivity to tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) [18].

ALK and ROS1 Rearrangements

Anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) and ROS proto-oncogene 1 (ROS1) are receptor tyrosine kinases that undergo oncogenic activation through chromosomal rearrangements. The most common is the EML4-ALK fusion, resulting from an inversion on chromosome 2p that creates a chimeric protein with constitutive ALK activity [18]. Similarly, ROS1 fusions produce chimeric proteins that activate downstream signaling pathways. Both ALK and ROS1 rearrangements are predominantly found in lung adenocarcinomas of never-smokers or light smokers and are generally mutually exclusive with EGFR and KRAS mutations [18] [20].

MET Exon 14 Skipping Mutations

The MET proto-oncogene encodes the hepatocyte growth factor receptor (HGFR). MET exon 14 skipping mutations result in a truncated protein that lacks the juxtamembrane domain containing the CBL E3-ubiquitin ligase binding site, leading to decreased receptor degradation and sustained oncogenic signaling [20]. These alterations activate both the MAPK and PI3K/AKT pathways through direct and indirect mechanisms [18].

KRAS Signaling and Constitutive Activation

KRAS is a small GTPase that functions downstream of various growth factor receptors, including EGFR. It cycles between GTP-bound (active) and GDP-bound (inactive) states to regulate cell growth, proliferation, and survival through the MAPK and PI3K/AKT pathways [19]. Oncogenic mutations, primarily at codon G12 (especially G12C), hinder GTP hydrolysis, maintaining KRAS in a constitutively active state that drives uncontrolled proliferation [19] [21]. KRAS mutations are strongly associated with tobacco smoking and typically exhibit mutual exclusivity with other driver mutations, though rare co-occurrences have been documented [19] [23].

Detection Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Comprehensive molecular profiling is essential for identifying targetable drivers in NSCLC. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has emerged as the preferred methodology for simultaneous detection of multiple genomic alterations. The following workflow diagram outlines a standardized testing protocol.

Sample Collection and Nucleic Acid Extraction

- Tissue Biopsy: Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue specimens from core needle biopsies or surgical resections represent the gold standard for molecular testing [21]. Optimal tissue preservation is critical for preserving nucleic acid integrity.

- Liquid Biopsy: Circulating cell-free DNA (cfDNA) from plasma enables non-invasive detection of tumor-derived DNA. The NILE study demonstrated that combining cfDNA with tissue testing increased the identification of guideline-recommended biomarkers by 48% [21]. Liquid biopsy is particularly valuable when tissue quantity is insufficient or sequential monitoring is required.

- Nucleic Acid Extraction: DNA and RNA are co-extracted from FFPE sections or liquid biopsy samples using commercial kits. DNA is utilized for mutation detection, while RNA is preferred for fusion detection. Quality control measures include spectrophotometric (Nanodrop) and fluorometric (Qubit) quantification, with RNA integrity number (RIN) assessment for RNA samples.

Library Preparation and Sequencing

- Targeted NGS Panels: Amplification-based or hybrid capture-based approaches enrich for cancer-relevant genes. The Oncomine Comprehensive Assay v3 exemplifies a comprehensive panel covering hotspot mutations, copy number variations, and gene fusions relevant to NSCLC [24].

- Library Quantification and Normalization: Libraries are quantified via qPCR or fluorometric methods, normalized, and pooled for multiplexed sequencing.

- Sequencing: Most clinical implementations utilize Illumina platforms (NovaSeq, MiSeq) or Ion Torrent systems (Genexus, S5) with coverage depths of 500-1000x for tissue and 3000-5000x for liquid biopsy to detect low-frequency variants.

Bioinformatic Analysis and Interpretation

- Primary Analysis: Base calling, demultiplexing, and quality control (FastQC).

- Secondary Analysis: Alignment to reference genome (hg38) using optimized aligners (BWA, STAR) followed by variant calling with specialized tools (MuTect2 for SNVs, DELLY for fusions, CNVkit for copy number alterations).

- Tertiary Analysis: Variant annotation (OncoKB, CIViC) filters and prioritizes clinically actionable alterations. Interpretation follows established guidelines from AMP/ASCO/CAP to classify variants based on evidence for therapeutic actionability.

Complementary Detection Methods

While NGS provides comprehensive profiling, orthogonal validation methods remain important:

- Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (FISH): Gold standard for detecting ALK and ROS1 rearrangements [16].

- Immunohistochemistry (IHC): Screening tool for ALK and ROS1 fusions, with confirmation required by FISH or NGS [16].

- Digital PCR: Ultra-sensitive method for monitoring specific mutations (e.g., T790M) during treatment.

Therapeutic Targeting and Clinical Management

Approved Targeted Therapies

Table 2 summarizes current standard targeted therapies for oncogenic drivers in NSCLC, including drug mechanisms and clinical applications.

Table 2: Approved Targeted Therapies for Oncogenic Drivers in NSCLC

| Driver Alteration | Therapeutic Class | Representative Agents | Clinical Context | Key Trial Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EGFR | EGFR TKIs | Osimertinib, Erlotinib, Afatinib | First-line for common mutations; Osimertinib for T790M resistance | Superior PFS vs. chemotherapy (HR 0.46); CNS activity [19] [20] |

| ALK | ALK Inhibitors | Alectinib, Lorlatinib, Crizotinib | First-line for rearrangements; later-generation agents for resistance | Alectinib: median PFS 34.8 months; superior CNS penetration [20] |

| ROS1 | ROS1 Inhibitors | Entrectinib, Crizotinib, Lorlatinib | First-line for rearrangements; sequential therapy at progression | Entrectinib: ORR 77%, intracranial response 55% [20] |

| MET | MET Inhibitors | Capmatinib, Tepotinib | MET exon 14 skipping mutations | Capmatinib: ORR 68% in treatment-naïve, 41% in pretreated [19] [20] |

| KRAS G12C | KRAS G12C Inhibitors | Sotorasib, Adagrasib | Previously treated advanced NSCLC | Sotorasib: ORR 41%, mDOR 11.1 months; Adagrasib: ORR 43% [21] [20] |

Resistance Mechanisms and Sequential Therapy

Despite initial efficacy, acquired resistance invariably develops through multiple mechanisms:

- On-Target Resistance: Secondary mutations within the target gene (e.g., EGFR T790M and C797S mutations, KRAS G12C allelic switching) reduce drug binding affinity [19].

- Off-Target Resistance: Activation of bypass signaling pathways (e.g., MET amplification, HER2 amplification) maintains downstream signaling despite target inhibition [18] [17].

- Histological Transformation: Transformation to small cell lung cancer or epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition represents a non-genetic resistance mechanism [19].

Sequential therapy strategies guided by repeat biopsy or liquid biopsy monitoring can address resistance. For example, upon development of EGFR T790M resistance to first-generation TKIs, switching to osimertinib can restore disease control [19]. Similarly, upon progression on first-generation ALK inhibitors, later-generation agents (alectinib, lorlatinib) can overcome common resistance mutations [20].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for NSCLC Oncogenic Driver Investigation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Line Models | NCI-H1975 (EGFR L858R/T790M), NCI-H3122 (EML4-ALK), NCI-H358 (KRAS G12C) | In vitro drug screening, resistance mechanism studies, combination therapy development |

| Animal Models | Patient-derived xenografts (PDXs), Genetically engineered mouse models (GEMMs) | In vivo efficacy studies, biomarker validation, preclinical drug development |

| NGS Assay Kits | Oncomine Comprehensive Assay v3, Illumina TruSight Oncology 500 | Comprehensive genomic profiling, biomarker discovery, clinical validation studies |

| IHC Antibodies | Anti-ALK (D5F3), Anti-ROS1 (D4D6), Anti-PD-L1 (22C3, 28-8) | Protein expression analysis, diagnostic validation, translational research |

| cfDNA Reference Materials | Seraseq ctDNA Mutation Mix, Horizon Multiplex I cfDNA Reference | Liquid biopsy assay development, analytical validation, quality control |

The identification and therapeutic targeting of oncogenic drivers has fundamentally transformed the management of NSCLC, shifting treatment paradigms from histology-based to molecularly-guided approaches. EGFR, ALK, ROS1, MET, and KRAS mutations represent clinically actionable targets with approved therapies that significantly improve patient outcomes compared to conventional chemotherapy. Ongoing research efforts are focused on addressing several key challenges: overcoming therapeutic resistance through next-generation inhibitors and rational combination therapies; developing innovative targeting strategies for historically "undruggable" targets; and optimizing biomarker detection technologies to enable comprehensive molecular profiling for all patients. The integration of multi-omics approaches—including proteogenomic analyses—promises to further refine molecular classification and identify novel therapeutic vulnerabilities, particularly in NSCLC subsets lacking currently actionable drivers [17]. As the field continues to evolve, the precision oncology paradigm in NSCLC will increasingly incorporate complex biomarker signatures, treatment sequencing algorithms, and innovative clinical trial designs to maximize therapeutic benefit for molecularly-defined patient populations.

Oncogenic gene fusions, resulting from chromosomal rearrangements such as translocations, inversions, or deletions, represent a class of potent driver mutations in cancer [25]. These hybrid genes produce fusion proteins that can function as strong oncogenic drivers, leading to uncontrolled cell proliferation and survival [26]. The constitutive activation of tyrosine kinases, such as MET, RET, and NTRK, is a common oncogenic mechanism whereby the fusion protein provides ligand-independent, constitutive activation of downstream molecular signaling pathways [26]. In up to 17% of all solid tumors, at least one gene fusion can be identified, making them compelling targets for precision therapy [26].

The clinical significance of these fusions is profound. They are clonal mutations, meaning they represent a personal cancer target involving all cancer cells of that patient, not just a subpopulation within the cancer mass [26]. This characteristic makes them ideal targets for both fusion signal disruption and immune signal targeting strategies. The discovery of these fusions has been accelerated by advancements in next-generation sequencing (NGS) and bioinformatic techniques, enabling the expansion of therapeutic opportunities for subpopulations of patients with fusion gene expression [26] [27].

Biological Mechanisms of Fusion-Driven Oncogenesis

Common Structural and Functional Themes

Oncogenic fusion proteins typically arise through in-frame mutations that affect exonic regions of two protein-coding genes [25]. The structure of these fusions often follows several key patterns:

- Kinase Activation: The most common product is constitutive kinase activation, where one fusion partner is a kinase and the other provides a dimerization domain, leading to ligand-independent dimerization and activation [26] [25]. This mechanism is central to MET, RET, and NTRK fusions.

- Aberrant Transcription: Some chimeric proteins include a transcription factor, leading to cell transformation through altered gene expression programs [26].

- Promoter-Driven Overexpression: Fusion of a strong promoter to a proto-oncogene can augment the expression of the oncogene, driving tumorigenesis [26].

- Tumor Suppressor Inactivation: More rare fusions can result in the inactivation of tumor-suppressor genes through deletion of the promoter region [26].

Downstream Signaling Pathways

The primary oncogenic signaling pathways activated by MET, RET, and NTRK fusions include:

- MAPK Pathway: Regulates cell proliferation and differentiation

- PI3K/AKT Pathway: Controls cell survival and metabolism

- JAK/STAT Pathway: Influences growth and immune responses

These pathways frequently exhibit cross-talk, creating a complex signaling network that sustains the malignant phenotype and creates challenges for therapeutic targeting.

The following diagram illustrates the common signaling pathways activated by MET, RET, and NTRK fusion proteins:

MET Fusions: Biology and Therapeutic Targeting

Prevalence and Oncogenic Mechanisms

MET gene fusions, while relatively rare, drive oncogenesis in multiple cancer types through constitutive activation of the MET receptor tyrosine kinase. The fusion typically partners the intracellular kinase domain of MET with various 5' partner genes that provide dimerization domains, facilitating ligand-independent activation.

Approved and Investigational Therapies

While the search results provide limited specific information on MET fusions, they are known to be targeted by MET-specific tyrosine kinase inhibitors and multikinase inhibitors in clinical development.

Table 1: Prevalence of MET, RET, and NTRK Fusions Across Solid Tumors

| Fusion Type | Common Cancer Types | Prevalence | Key Fusion Partners |

|---|---|---|---|

| RET | Papillary Thyroid Cancer, NSCLC, Medullary Thyroid Cancer | 6-10% of PTC, 1-2% of NSCLC [28] | KIF5B, CCDC6, NCOA4 [25] |

| NTRK | Secretory Breast Carcinoma, Congenital Infantile Fibrosarcoma, Mammary-analog Secretory Carcinoma | >80% in rare tumors, <1-5% in common carcinomas [25] [29] | ETV6, TPM3, TPR [29] |

| MET | NSCLC, Renal Cell Carcinoma, other solid tumors | Variable, generally rare across tumor types | Multiple partners including CAPZA2, HLA-DRB1, PTPRZ1 |

RET Fusions: From Biology to Precision Therapy

Molecular Pathogenesis and Prevalence

RET (Rearranged During Transfection) fusions are oncogenic drivers resulting from chromosomal rearrangements that fuse the 3' kinase domain of RET with the 5' region of various partner genes [25] [28]. This rearrangement leads to constitutive, ligand-independent activation of the RET kinase and downstream oncogenic signaling pathways, primarily RAS/MAPK and PI3K/AKT [28]. RET fusions are characterized by their occurrence in specific cancer types:

- Thyroid Cancer: RET fusions are present in approximately 6-10% of papillary thyroid cancer (PTC) cases and 6% of poorly differentiated thyroid cancer (PDTC) cases, with notably higher prevalence (60-80%) in radiation-induced thyroid cancer [28].

- Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC): RET rearrangements are found in 1-2% of NSCLC cases [25].

- Other Cancers: RET fusions have also been identified at lower frequencies in colorectal, breast, and other cancer types [25].

Clinical data indicate that RET-driven tumors are particularly aggressive, showing higher likelihood of extrathyroid extension, multifocality, and distant metastasis compared to RAS-mutated tumors [28].

Approved RET Inhibitors and Clinical Efficacy

The development of selective RET inhibitors has revolutionized treatment for RET-altered cancers, offering improved efficacy and reduced off-target toxicity compared to earlier multi-kinase inhibitors.

Table 2: Approved Selective RET Inhibitors and Clinical Efficacy

| Drug Name | Generation | Key Clinical Trial | Approved Indications | Efficacy (ORR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Selpercatinib | First selective | LIBRETTO-001 [28] | RET fusion-positive NSCLC and thyroid cancer | 73% in MTC, 89% in RET fusion-positive thyroid cancer [28] |

| Pralsetinib | First selective | NCT03037385 [28] | RET fusion-positive NSCLC and thyroid cancer | 71% in RET-mutated MTC [28] |

| LOXO-260 | Next-generation | In development [28] | Designed to overcome resistance (G810 mutations) | Preclinical activity against G810C/S/R mutations [30] |

Resistance Mechanisms and Next-Generation Approaches

Despite the remarkable efficacy of first-generation selective RET inhibitors, resistance inevitably develops through multiple mechanisms:

- On-target mutations: The G810C/S/R mutations in the RET kinase domain represent the most common resistance mechanism, reducing drug binding affinity [30].

- Bypass activation: Off-target resistance mechanisms include activation of alternative signaling pathways such as KRAS/MET that circumvent RET inhibition [28] [31].

- DNA damage repair activation: Recent research has identified that DNA damage repair (DDR) pathways enable a drug-tolerant persister state in RET-fusion NSCLC that precedes TKI resistance [30].

Novel therapeutic strategies are under investigation to overcome resistance:

- Next-generation RET inhibitors: Compounds like SNH-110 show potent activity against RET with G810 resistance mutations in preclinical models [30].

- PROTAC platforms: Proteolysis Targeting Chimeras (PROTACs) such as YW-N-7 simultaneously inhibit and degrade oncogenic RET protein, showing significant tumor growth inhibition in RET fusion models [30].

- Combination therapies: Dual targeting of RET and SRC with drugs like dasatinib or eCF506 (NXP900) demonstrates synergistic effects in RET+ cancer cells and can restore sensitivity in selpercatinib-resistant models [31].

- XPO1 inhibition: Combining the RET inhibitor selpercatinib with selinexor, an XPO1-blocking drug, dramatically reduces drug-tolerant persister cells and delays cancer recurrence in preclinical models [30].

The following workflow summarizes the experimental approach for investigating RET inhibitor resistance mechanisms:

NTRK Fusions: A Paradigm for Tissue-Agnostic Drug Development

Biology and Prevalence of NTRK Fusions

The NTRK (NeuroTrophic Tyrosine Receptor Kinase) family includes NTRK1, NTRK2, and NTRK3 genes, encoding TrkA, TrkB, and TrkC receptor tyrosine kinases, respectively [32]. NTRK fusions represent a paradigm in precision oncology due to their occurrence across diverse tumor types and their high responsiveness to targeted inhibition. These fusions typically result in the 3' kinase domain of NTRK genes fusing with various 5' partner genes, leading to ligand-independent constitutive kinase activation and downstream oncogenic signaling through PI3K, Akt, Ras, and MAPK pathways [32] [29].

The prevalence of NTRK fusions follows two distinct patterns:

- High Prevalence in Rare Tumors: NTRK fusions occur in >80% of cases of infantile congenital fibrosarcoma, secretory breast carcinoma, and mammary-analog secretory carcinoma of the salivary gland [25].

- Low Prevalence in Common Cancers: In more common tumor types such as lung, colorectal, and pancreatic cancers, NTRK fusions are generally found in <1-5% of cases [29].

Fusion-Negative NTRK Overexpression and Signaling

Recent evidence indicates that NTRK overexpression can also occur independently of gene fusion events through alternative genomic or epigenetic alterations such as gene amplification or promoter hypomethylation [32]. This fusion-negative NTRK overexpression represents a distinct and less-explored mechanism of dysregulation that may contribute to oncogenic signaling in colorectal and other cancers, potentially functioning as a biomarker for kinase inhibitor response even in the absence of canonical fusions [32].

Approved TRK Inhibitors and Clinical Applications

The development of TRK inhibitors represents a landmark achievement in precision medicine, leading to tissue-agnostic drug approvals based on molecular alterations rather than tumor histology.

Table 3: Approved NTRK Inhibitors and Clinical Applications

| Drug Name | Type | Key Features | Approval Status | Efficacy in NTRK Fusion-Positive Cancers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Larotrectinib | First-generation TRK inhibitor | High selectivity, CNS activity | Tissue-agnostic approval for NTRK fusion-positive solid tumors | High response rates across multiple tumor types [29] |

| Entrectinib | First-generation TRK inhibitor | Targets TRKA/B/C, ROS1, and ALK | Tissue-agnostic approval for NTRK fusion-positive solid tumors | Potent activity against various NTRK fusions [32] [29] |

| Repotrectinib | Next-generation TRK inhibitor | Designed to overcome resistance | In clinical development | Active against solvent-front resistance mutations [29] |

Research Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Detection Methods for Oncogenic Fusions

The accurate detection of MET, RET, and NTRK fusions is critical for appropriate patient selection for targeted therapies. Current methodologies include:

- Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS): RNA-based NGS is particularly efficient for fusion detection as it can identify functional, expressed fusions regardless of genomic breakpoint location [25].

- Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (FISH): A well-established method that uses fluorescently labeled DNA probes to detect chromosomal rearrangements [25].

- Immunohistochemistry (IHC): Can be used as a screening tool for protein overexpression resulting from gene fusions, though it lacks the specificity of molecular methods [25].

Each method has distinct advantages and limitations regarding sensitivity, specificity, throughput, and ability to detect novel fusion partners, necessitating careful consideration based on clinical context and available resources.

3D CRISPR Screening Protocol for Resistance Mechanism Identification

A recent study employed sophisticated 3D CRISPR screening to identify novel resistance mechanisms to RET-targeted therapies [30]. The detailed methodology is as follows:

Step 1: Cell Culture Preparation

- Utilize RET fusion-positive cell lines (e.g., LC-2/ad with CCDC6-RET fusion and LCC190 with CCDC6-RET fusion)

- Establish 3D culture conditions using appropriate extracellular matrix substrates to better mimic the tumor microenvironment

Step 2: Genome-Wide CRISPR Library Transduction

- Employ a genome-wide CRISPR knockout (GeCKO) library containing approximately 65,000 guide RNAs targeting all human genes

- Transduce cells at low multiplicity of infection (MOI ~0.3) to ensure single guide RNA integration

- Select transduced cells with appropriate antibiotics (e.g., puromycin) for 5-7 days

Step 3: RET Inhibitor Treatment and Resistance Selection

- Treat cells with selective RET inhibitors (selpercatinib or pralsetinib) at clinically relevant concentrations

- Maintain treatment for 3-4 weeks to allow emergence of resistant populations

- Include untreated control cells cultured in parallel

Step 4: Genomic DNA Extraction and Next-Generation Sequencing

- Harvest genomic DNA from both resistant and control cells using standard protocols

- Amplify integrated CRISPR guide RNA sequences with barcoded primers for multiplexing

- Sequence amplified products on Illumina platform to determine guide RNA abundance

Step 5: Bioinformatic Analysis

- Align sequencing reads to the reference guide RNA library

- Use MAGeCK or similar algorithms to identify significantly enriched or depleted guide RNAs in resistant versus control cells

- Perform pathway enrichment analysis on genes whose knockout conferred resistance

Step 6: Validation Studies

- Validate top hits using individual guide RNAs in parental cell lines

- Confirm mechanism through rescue experiments and downstream signaling analysis

This approach successfully identified MIG6 loss as a key resistance mechanism, which leads to EGFR pathway hyperactivation and bypass signaling [30].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Reagents for Investigating Kinase Fusions

| Reagent/Cell Line | Source/Identifier | Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| LC-2/ad Cell Line | Japanese Foundation for Cancer Research [30] | RET fusion (CCDC6-RET) research | Human lung cancer cell line with endogenous CCDC6-RET fusion |

| BaF3 KIF5B-RET Model | University of Southern Florida [30] | RET fusion signaling and drug screening | Murine pro-B cell line engineered with KIF5B-RET fusion |

| Genome-Wide CRISPR Library | Commercial sources (e.g., Addgene) | Functional genomics screens | Comprehensive guide RNA collection for knockout screens |

| PROTAC Molecule YW-N-7 | University of Southern Florida [30] | Targeted protein degradation research | Bivalent molecule that recruits RET to E3 ubiquitin ligase |

| Next-Generation RET Inhibitor SNH-110 | ScinnoHub Pharmaceutical [30] | Overcoming resistance studies | Potent against RET with G810C/S/R resistance mutations |

Future Directions and Clinical Implications

The field of fusion protein-targeted therapy continues to evolve rapidly, with several promising directions emerging:

Novel Therapeutic Platforms

- PROTAC Technology: The development of Proteolysis Targeting Chimeras (PROTACs) for RET and other kinases represents a paradigm shift from inhibition to targeted protein degradation [30]. The lead compound YW-N-7 has demonstrated significant tumor growth inhibition in RET fusion models by simultaneously inhibiting and degrading oncogenic RET protein [30].

- Next-Generation Inhibitors: Compounds such as SNH-110, LOXO-260, enbezotinib, SY-5007, and TY-1091 are under investigation to address the limitations of current RET inhibitors, particularly against resistance mutations like G810C/S/R [30] [28].

- Rational Combination Therapies: Based on resistance mechanism insights, combinations of selective RET inhibitors with SRC inhibitors (e.g., dasatinib, eCF506) or XPO1 inhibitors (e.g., selinexor) show promise in preclinical models for both treatment-naïve and resistant settings [30] [31].

Clinical Trial Design and Personalized Medicine

The successful targeting of MET, RET, and NTRK fusions has validated basket trial designs in which patients are enrolled based on molecular alterations rather than tumor histology [33]. Studies like ASCO's TAPUR (Targeted Agent and Profiling Utilization Registry) demonstrate the feasibility of this approach across diverse patient populations and community practice settings [33]. Future trials will need to incorporate comprehensive molecular profiling, adaptive designs, and careful consideration of demographic factors that may influence genomic alteration prevalence and treatment response.

MET, RET, and NTRK fusions represent compelling therapeutic targets in precision oncology, driving oncogenesis across diverse cancer types through constitutive activation of critical signaling pathways. The development of selective inhibitors for these fusion proteins has transformed outcomes for patients with these alterations, particularly in the case of RET and NTRK fusions where tissue-agnostic approvals have established new paradigms in drug development. Despite remarkable progress, challenges remain including therapeutic resistance, tumor heterogeneity, and the need for more effective biomarkers. Ongoing research focusing on novel therapeutic platforms, combination strategies, and understanding resistance mechanisms promises to further advance this dynamic field, ultimately improving outcomes for patients with fusion-driven cancers.

Heterogeneity of Genomic Alterations in Hematologic Versus Solid Malignancies

The characterization of genomic alterations has become a cornerstone of modern oncology, providing critical insights into the mechanisms driving carcinogenesis and revealing potential therapeutic vulnerabilities. However, the nature and extent of these genomic alterations differ profoundly between hematologic and solid malignancies, with significant implications for diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment selection. This heterogeneity stems from fundamental differences in cellular origin, microenvironment, and evolutionary pressures that shape the genomic landscape of these cancer types.

Within the context of genomic alterations driving malignancy and therapeutic target research, understanding these distinctions is paramount for drug development professionals seeking to design effective targeted therapies. Hematologic malignancies often demonstrate more uniform genomic landscapes with recurrent, tractable driver mutations, while solid tumors frequently exhibit extensive spatial and temporal heterogeneity that complicates therapeutic targeting. This technical guide provides an in-depth comparison of genomic alteration heterogeneity between these cancer categories, detailing the methodologies for their characterization, and discussing the implications for targeted therapy development.

Fundamental Disparities in Genomic Alteration Patterns

Tumor Mutational Burden and Genetic Instability

The genomic landscape of hematologic and solid malignancies differs significantly in terms of mutational burden and patterns of genetic instability. Solid tumors generally exhibit higher tumor mutational burdens (TMB) compared to hematologic malignancies, which is reflected in their more complex genomic architectures [34]. This disparity arises from differences in cellular origin, exposure to carcinogens, and DNA repair mechanisms.

Table 1: Comparative TMB and Genetic Instability Patterns

| Characteristic | Hematologic Malignancies | Solid Tumors |

|---|---|---|

| Median TMB | Generally lower (<5 mutations/Mb in many subtypes) [34] | Generally higher (varies by cancer type and exposure history) |

| TMB Range | More constrained across subtypes | Wider variation between and within cancer types |

| Influencing Factors | Age-related differences (CYAs vs OAs) [34] | Tissue origin, carcinogen exposure, DNA repair defects |

| Lymphoid vs Myeloid | Lymphoid tumors often have higher TMB than myeloid tumors [34] | Not applicable |

| Age Correlation | OAs show 1.35-fold higher TMB in lymphoid tumors vs CYAs [34] | Generally increases with age and exposure duration |

Recurrent Alteration Types and Signatures

The types of genomic alterations that recurrently occur in hematologic versus solid malignancies demonstrate notable differences in both quality and distribution. Hematologic malignancies are characterized by distinct patterns of mutations, copy number alterations, and structural variations that often differ from those observed in solid tumors.

Table 2: Characteristic Genomic Alterations by Malignancy Type

| Alteration Type | Hematologic Malignancies | Solid Tumors |

|---|---|---|

| Commonly Mutated Genes | TP53, TET2, DNMT3A, NRAS, KRAS, ID3, KIT [34] | TP53, CDKN2A, TUBB3, ER/PR positive status [33] |

| Copy Number Alterations | More prevalent in CYAs; specific genes (ARID1B, MYB) show age-related patterns [34] | Extensive heterogeneity; high spatial and temporal variation |

| Structural Variants | High frequency of driver gene fusions, particularly in CYAs [34] | Less frequent as primary drivers; more passenger events |

| Age-Related Patterns | TP53, TET2, DNMT3A mutations increase with age; NRAS, KRAS, ID3 more common in CYAs [34] | More complex relationship with age and exposure history |

Methodological Approaches for Characterizing Genomic Heterogeneity

Comprehensive Genomic Profiling Techniques

Advanced genomic profiling technologies have revolutionized our ability to characterize the heterogeneity of genomic alterations across cancer types. The following experimental protocols represent state-of-the-art approaches for comprehensive genomic assessment:

Protocol 1: Integrated DNA and RNA Sequencing for Hematologic Malignancies

This protocol is based on validated approaches from clinical studies demonstrating high detection rates of clinically relevant alterations [35] [36].

Sample Preparation: Extract DNA and RNA from patient samples (100-500ng input required). For hematologic malignancies, bone marrow aspirates or blood samples are typically used, while solid tumors require tissue biopsies.

Library Construction:

- Fragment DNA enzymatically using NEB Ultra II FS reagents

- Perform end repair, 5' phosphorylation, A-tailing, and adapter ligation

- For RNA sequencing: DNase treatment followed by ribodepletion

- Use NEBNext Ultra II Directional RNA library prep kit

Target Enrichment:

- Hybrid capture using IDT xGen Exome Research Panel v1.0 enhanced with xGenCNV Backbone and Cancer-Enriched Panels

- Custom gene panels (e.g., 405 genes for DNA, 265 genes for RNA in FoundationOne Heme) [36]

Sequencing:

- Generate paired-end 151-bp reads on Illumina platforms (HiSeq 4000 or NovaSeq 6000)

- Target minimum coverage of 100x for DNA, 50M reads for RNA

Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Align to GRCh38 using BWA (DNA) or STAR-Fusion (RNA)

- Remove duplicates using samblaster-v.0.1.22

- Perform base quality score recalibration using GATK

- Call germline variants with GATK's HaplotypeCaller

- Detect somatic SNVs/indels with MuTect2

- Identify CNVs using GATK and VarScan2

- Call fusions using ensemble approach (STARfusion, MapSplice, FusionCatcher, FusionMap, JAFFA, CICERO, Arriba) [35]

Protocol 2: Multi-Regional Sequencing for Spatial Heterogeneity Assessment in Solid Tumors

This approach addresses the significant spatial heterogeneity characteristic of solid tumors [37] [38].

Multi-Regional Sampling:

- Collect multiple spatially separated samples from primary tumor (minimum 5 regions for 80% variant detection probability) [37]

- Include matched metastatic lesions when available

- Collect normal tissue as germline comparator

Whole Exome/Genome Sequencing:

- Process each region independently through library preparation

- Perform whole exome capture or whole genome sequencing

- Sequence to high coverage (150-200x for tumor, 60x for normal)

Clonal Decomposition:

- Identify clonal mutations (present in all regions)

- Identify subclonal mutations (private to specific regions)

- Reconstruct phylogenetic relationships between regions

Heterogeneity Quantification:

- Calculate mutant allele frequency distributions

- Determine genomic distance between regions

- Estimate cancer cell fractions

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Genomic Heterogeneity Studies

| Reagent/Platform | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| IDT xGen Exome Research Panel | Target enrichment for exome sequencing | Comprehensive variant discovery across hematologic and solid malignancies [35] |

| NEB Ultra II FS DNA Library Prep Kit | Library preparation for NGS | Fragmentation, end repair, A-tailing, and adapter ligation for DNA sequencing [35] |

| NEBNext Ultra II Directional RNA Library Prep Kit | RNA library preparation | Maintains strand specificity for transcriptome and fusion analysis [35] |

| FoundationOne Heme | Integrated DNA/RNA profiling | Clinical-grade comprehensive genomic profiling for hematologic malignancies [36] |

| Illumina HiSeq/NovaSeq Platforms | High-throughput sequencing | Generation of paired-end sequencing data for genomic studies [35] |

| Churchill Bioinformatics Pipeline | Secondary NGS analysis | Comprehensive workflow from alignment to variant calling [35] |