Antitumor Immunity and Treatment Toxicity: Unraveling the Dual Mechanisms of Cancer Immunotherapy

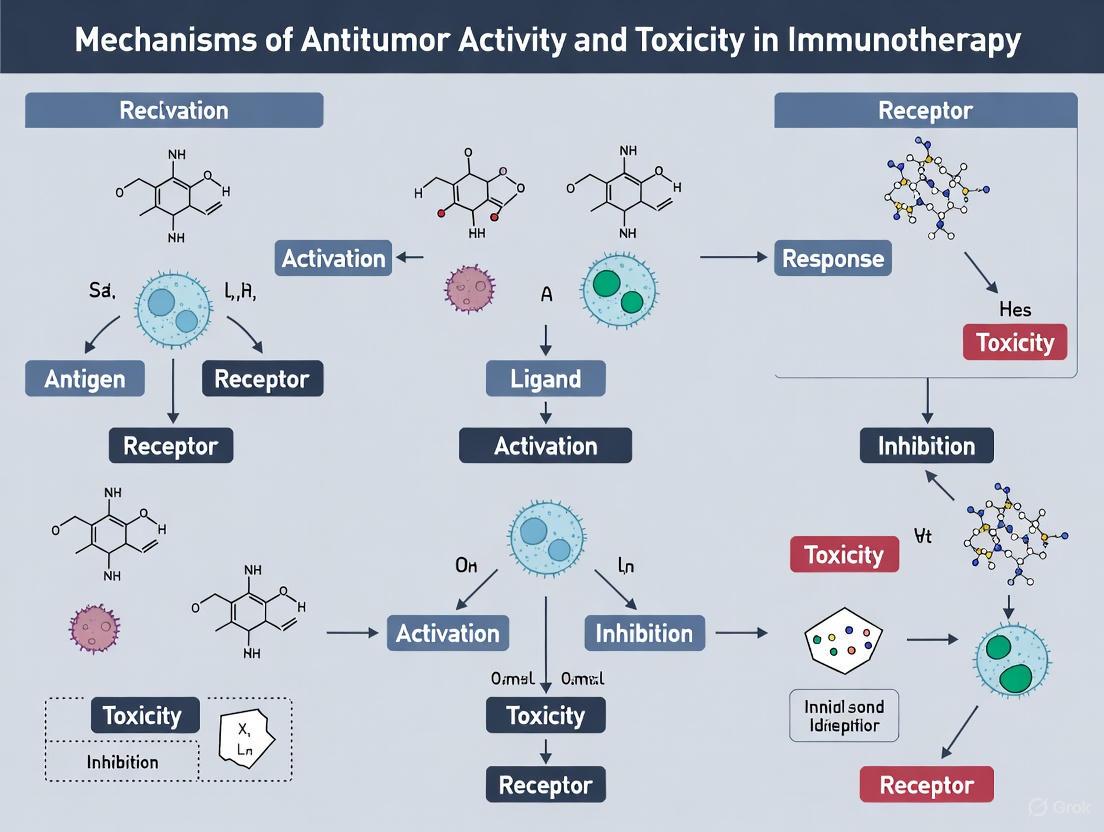

This review provides a comprehensive analysis of the molecular and cellular mechanisms that underpin both the efficacy and toxicity of cancer immunotherapy.

Antitumor Immunity and Treatment Toxicity: Unraveling the Dual Mechanisms of Cancer Immunotherapy

Abstract

This review provides a comprehensive analysis of the molecular and cellular mechanisms that underpin both the efficacy and toxicity of cancer immunotherapy. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it synthesizes foundational science on immune checkpoint biology, the tumor microenvironment, and adoptive cell therapies. The article further explores the physiological basis of immune-related adverse events (irAEs), with a focus on cardiovascular, dermatological, and systemic toxicities. It critically evaluates current strategies to decouple antitumor activity from toxicity, including biomarker discovery, microbiome engineering, and combination treatments. By integrating foundational exploration with methodological applications, troubleshooting, and comparative validation, this work aims to inform the development of safer, more precise immunotherapeutic interventions.

Core Principles: Deconstructing the Immunological Mechanisms of Antitumor Activity

The cancer-immunity cycle provides a comprehensive framework for understanding the sequential events required to generate effective anti-cancer immune responses. This iterative process begins with T cell-mediated tumor cell killing, which leads to antigen presentation and T cell stimulation, creating a self-perpetuating cycle of immune activity against malignant cells [1] [2]. The cycle encompasses seven distinct yet interconnected steps that orchestrate the complex interplay between tumor cells and immune surveillance: (1) cancer cell death releases neoantigens and tumor-associated antigens; (2) antigen-presenting cells capture and process these antigens; (3) dendritic cells present antigens to prime and activate T cells in lymphoid organs; (4) activated effector T cells migrate through the bloodstream; (5) T cells infiltrate tumor sites; (6) T cells recognize cancer cells; and (7) cytotoxic T lymphocytes execute tumor cell killing, releasing additional antigens to perpetuate the cycle [3].

Understanding the cancer-immunity cycle is fundamental to advancing immunotherapy research, as any step can become rate-limiting, rendering the immune system unable to control tumor growth [2]. The remarkable progress in cancer immunotherapy over the past decade has led to a refined understanding of this cycle, including the evolving mechanism of checkpoint inhibition, the role of dendritic cells in sustaining anti-tumor immunity, and the dual nature of the tumor microenvironment in both facilitating and suppressing anti-cancer responses [2]. This whitepaper examines the core mechanisms of the cancer-immunity cycle within the broader context of antitumor activity and immunotherapy toxicity research, providing technical guidance and experimental approaches for researchers and drug development professionals.

Core Steps of the Cancer-Immunity Cycle: Mechanisms and Technical Assessment

Step 1: Antigen Release and Immunogenic Cell Death

The cancer-immunity cycle initiates with antigen release through immunogenic cell death (ICD), a critical process that transforms dying tumor cells into a therapeutic vaccine in situ. ICD involves the release of damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) including calreticulin, ATP, and HMGB1 [4] [5]. These DAMPs serve as potent adjuvants that attract and activate antigen-presenting cells, particularly dendritic cells, thereby bridging innate and adaptive immunity [4].

The release of tumor-derived DNA during ICD activates the cGAS-STING pathway, a crucial mechanism of innate immune sensing within the tumor microenvironment [4] [6]. This pathway triggers type I interferon responses that enhance dendritic cell maturation and cross-priming of T cells. Recent research has also elucidated the role of extracellular vesicles, particularly exosomes, in shuttling tumor antigens to dendritic cells, expanding the scope of antigen presentation beyond traditional cellular mechanisms [4].

Table 1: Key DAMPs in Immunogenic Cell Death and Their Functions

| DAMP Molecule | Release Mechanism | Immune Function | Receptors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Calreticulin | Exposed on cell surface during ER stress | "Eat me" signal for phagocytes; enhances dendritic cell phagocytosis | LDL-receptor related protein-1 (LRP1) |

| ATP | Released from damaged mitochondria and cytoplasm | Chemoattractant for immune cells; activates NLRP3 inflammasome | P2X7, P2Y2 |

| HMGB1 | Released from nucleus during necrosis | Promotes antigen presentation; activates TLR4 pathway | TLR4, RAGE |

| Type I Interferons | Induced via cGAS-STING pathway | Dendritic cell activation; enhances cross-priming | IFNAR |

Step 2: Antigen Presentation and Dendritic Cell Maturation

Following antigen release, dendritic cells (DCs) play a pivotal role in capturing, processing, and presenting tumor antigens to T cells. Immature dendritic cells phagocytose tumor debris and undergo a complex maturation process that enables them to migrate to tumor-draining lymph nodes [4] [7]. The WDFY4 protein has been identified as critical for facilitating antigen transport to the cytosol, enabling cross-presentation of exogenous antigens on MHC class I molecules to CD8+ T cells [4].

The process of pyroptosis, a form of programmed cell death mediated by gasdermin proteins, induces potent immunogenic cell death that enhances dendritic cell maturation and establishes a positive feedback loop in the cancer-immunity cycle [4]. This creates a foundation for maximizing response rates to immune checkpoint blockade therapies. The efficiency of antigen presentation represents a crucial bottleneck in the cycle, as tumor-associated antigens alone often lack sufficient immunostimulatory potential to drive robust antitumor immunity without appropriate danger signals [5].

Step 3: T Cell Priming and Activation

In tumor-draining lymph nodes, mature dendritic cells present processed tumor antigens to naïve T cells, leading to T cell priming and activation [7]. The traditional three-signal model of T cell activation (TCR engagement, co-stimulation, and cytokine signaling) has been expanded to incorporate metabolic reprogramming as a crucial fourth signal [4]. The discovery of CD28-independent metabolic stimulation pathways, such as the ICOS-ICOSL axis, has broadened our understanding of T cell activation mechanisms [4].

Recent research has highlighted the importance of the actin cytoskeleton in T cell receptor microcluster formation and its impact on signal transduction, providing new insights into the spatial organization of T cell activation [4]. The role of innate-like T cells, particularly mucosal-associated invariant T (MAIT) cells and γδ T cells, in anti-tumor immunity has also gained recognition, although their precise functions in the cancer-immunity cycle warrant further investigation [4].

Table 2: Key Checkpoint Molecules Regulating T Cell Activation

| Checkpoint Molecule | Expression Pattern | Ligand(s) | Function in T Cell Biology | Therapeutic Inhibitors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTLA-4 | Induced on activated T cells; constitutively expressed on Tregs | B7-1 (CD80), B7-2 (CD86) | Attenuates early T cell activation; mediates bystander suppression | Ipilimumab, Tremelimumab |

| PD-1 | Induced on chronically activated T cells | PD-L1, PD-L2 | Limits T cell activity in peripheral tissues; promotes exhaustion | Nivolumab, Pembrolizumab |

| LAG-3 | Activated T cells, NK cells | MHC class II, GAL-3, LSECtin | Negatively regulates cellular proliferation and effector function | Relatlimab |

| TIM-3 | IFN-γ-producing T cells | Galectin-9, HMGB1, CEACAM-1 | Regulates macrophage activation and T cell exhaustion | Cobolimab, Sabatolimab |

| TIGIT | T cells, NK cells | CD155, CD112 | Suppresses T cell responses by competing with CD226 | Tiragolumab |

Steps 4-5: T Cell Trafficking and Tumor Infiltration

Activated effector T cells must traffic through the circulatory system and infiltrate tumor tissue to execute their cytotoxic functions [3] [7]. This process involves a coordinated sequence of tethering, rolling, adhesion, and transendothelial migration mediated by specific adhesion molecules and chemokine receptors. The CXCL13-CXCR5 axis has emerged as particularly important for T cell migration and the formation of tertiary lymphoid structures, which serve as crucial hubs for anti-tumor immunity despite their lack of capsules [4].

The tumor vasculature often presents a significant barrier to T cell infiltration, with increased expression of adhesion molecules such as VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 enhancing T cell extravasation. Additionally, the chemokine landscape within tumors, particularly the expression of CXCL9, CXCL10, and CXCL11, directs T cell migration into tumor nests. Recent studies have demonstrated that CD8+ T cells producing CXCL13 can effectively predict response to immunotherapy, highlighting the importance of trafficking mechanisms in therapeutic success [4].

Steps 6-7: Cancer Cell Recognition and Cytotoxic Killing

The final steps of the cycle involve T cell recognition of cancer cells through T cell receptor engagement with peptide-MHC complexes, followed by execution of cytotoxic function [7]. Effector T cells induce tumor cell death through multiple mechanisms, including the release of perforin and granzymes, Fas-FasL interactions, and cytokine-mediated apoptosis [7]. Successful tumor cell killing releases additional tumor antigens, thereby perpetuating the cycle and potentially broadening the immune response through epitope spreading [3].

During this process, T cells progress through a differentiation continuum from progenitor exhausted T cells with stem cell-like properties to terminally exhausted T cells that have lost replicative and effector functions [4]. The immunosuppressive mechanisms within the tumor immune microenvironment drive this exhaustion process, with terminally exhausted T cells (Texterm) maintaining the ability to produce effector molecules but lacking durable anti-tumor capacity [4].

Quantitative Modeling of the Cancer-Immunity Cycle

Computational Frameworks for Cycle Analysis

Mathematical modeling provides powerful approaches for unraveling the complex interactions between tumors and the immune system. The Quantitative Cancer-Immunity Cycle (QCIC) model employs differential equations to capture the biological mechanisms underlying the cancer-immunity cycle and predicts tumor evolution dynamics under various treatment strategies through stochastic computational methods [7]. This multi-compartmental, multi-scale ODE framework includes four distinct biological compartments: tumor-draining lymph node (TDLN), peripheral blood (PB), tumor microenvironment (TME), and bone marrow and thymus (BT) [7].

The QCIC model introduces the treatment response index (TRI) to quantify disease progression in virtual clinical trials and the death probability function (DPF) to estimate overall survival [7]. Through biomarker analysis, this modeling approach has identified tumor-infiltrating CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes as key predictors of disease progression and the tumor-infiltrating CD4+ Th1/Treg ratio as a significant determinant of survival outcomes in advanced metastatic colorectal cancer [7].

Table 3: Key Parameters in Quantitative Cancer-Immunity Cycle Modeling

| Parameter Category | Specific Parameters | Biological Significance | Measurement Techniques |

|---|---|---|---|

| T cell Dynamics | T cell activation rate, Proliferation rate, Exhaustion rate | Determines magnitude and duration of anti-tumor response | Flow cytometry, TCR sequencing |

| Tumor-Immune Interactions | Tumor kill rate by T cells, Immune suppression rate | Predicts efficacy of immune-mediated tumor control | Live-cell imaging, co-culture assays |

| Spatial Distribution | T cell infiltration rate, Chemokine gradients | Influences tumor penetration and contact with target cells | Multiplex IHC, spatial transcriptomics |

| Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic | Drug concentration, Target occupancy | Connects drug exposure to biological effect | Mass spectrometry, PET imaging |

Reaction-Diffusion Equations for Spatial Modeling

In addition to compartmental models, reaction-diffusion equations (RDEs) have been increasingly employed to describe molecular diffusion and intercellular interactions systematically [7]. These models excel at capturing the spatiotemporal dynamics of tumor-immune interactions, including adhesion processes and various cell migration patterns [7]. However, they typically fall short in explaining the biological mechanisms across different compartments of the organism, highlighting the complementary value of multi-compartmental approaches [7].

Experimental Methodologies for Investigating the Cancer-Immunity Cycle

Protocol 1: Assessing Immunogenic Cell Death In Vitro

Purpose: To quantify and characterize immunogenic cell death induced by therapeutic agents.

Materials:

- Tumor cell lines relevant to cancer type (e.g., MC38, B16F10, 4T1)

- Therapeutic agents (chemotherapeutics, targeted therapies, physical stressors)

- DAMP detection reagents: Anti-calreticulin antibody, ATP bioluminescence assay, HMGB1 ELISA kit

- Dendritic cells for co-culture experiments (e.g., bone marrow-derived DCs)

- Flow cytometry antibodies: CD11c, CD80, CD86, MHC class I/II

Procedure:

- Plate tumor cells in appropriate culture medium and allow to adhere overnight.

- Treat cells with ICD-inducing agents at predetermined concentrations (e.g., 1-10 μM for doxorubicin, 2-20 Gy for radiation).

- For surface calreticulin detection: Harvest cells at 12-24 hours post-treatment, stain with anti-calreticulin antibody, and analyze by flow cytometry.

- For ATP release: Collect supernatant at 4-6 hours post-treatment, measure ATP concentration using bioluminescence assay.

- For HMGB1 release: Collect supernatant at 24-48 hours post-treatment, quantify HMGB1 by ELISA.

- For functional assessment: Co-culture treated tumor cells with immature dendritic cells at 1:5 ratio (DC:tumor cell) for 24 hours, then analyze DC maturation markers by flow cytometry.

Validation: Compare DAMP release and DC maturation capacity across multiple ICD inducers and non-ICD inducing agents (e.g., UV-C irradiation) [5].

Protocol 2: T Cell Cytotoxicity and Exhaustion Assays

Purpose: To evaluate T cell-mediated killing of tumor cells and assess exhaustion markers.

Materials:

- Antigen-specific T cells (e.g., OT-I CD8+ T cells for ovalbumin model)

- Target tumor cells expressing cognate antigen

- Flow cytometry antibodies: CD3, CD8, CD44, CD62L, PD-1, TIM-3, LAG-3, TIGIT

- Cytokine detection: IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-2 ELISA kits

- Real-time cell analysis (RTCA) system or equivalent cytotoxicity assay

Procedure:

- Isolate and activate antigen-specific T cells using cognate peptide (1 μg/mL) and IL-2 (50 IU/mL) for 3 days.

- Label target tumor cells with cell tracker dye according to manufacturer's protocol.

- Co-culture T cells with target cells at various effector:target ratios (e.g., 1:1 to 30:1) in 96-well plates.

- For real-time cytotoxicity: Use RTCA system to monitor cell impedance every 15 minutes for 48-72 hours.

- For endpoint analysis: At 4-6 hours, measure target cell death by flow cytometry using viability dyes.

- For exhaustion markers: After 5-7 days of repeated stimulation, stain T cells for exhaustion markers and analyze by flow cytometry.

- For cytokine production: Collect supernatant at 24 hours and measure IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-2 by ELISA.

Validation: Include controls for antigen specificity (irrelevant peptide) and baseline T cell activation (anti-CD3/CD28 beads) [4] [8].

Key Signaling Pathways in the Cancer-Immunity Cycle

PD-1/PD-L1 Signaling Axis

The PD-1/PD-L1 pathway represents one of the most clinically relevant immune checkpoints, with multiple approved therapeutic inhibitors [8] [6]. PD-1 engagement by its ligands PD-L1 or PD-L2 transmits inhibitory signals that dampen T cell receptor signaling through dephosphorylation of key signaling molecules via recruitment of SHP-2 phosphatase [8]. Tumor cells frequently upregulate PD-L1 expression in response to inflammatory cytokines (particularly IFN-γ) and oncogenic signaling pathways such as PI3K/AKT [6].

Diagram 1: PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitory signaling in T cells.

cGAS-STING Pathway in Innate Immune Sensing

The cGAS-STING pathway plays a crucial role in innate immune sensing of tumor-derived DNA, connecting immunogenic cell death to adaptive immunity [4] [6]. Cytosolic DNA sensors activate this pathway, leading to type I interferon production and enhanced dendritic cell cross-priming of T cells. This pathway has emerged as a promising target for enhancing anti-tumor immunity, particularly in immunologically "cold" tumors [6].

Diagram 2: cGAS-STING pathway in anti-tumor immunity.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Reagents for Cancer-Immunity Cycle Investigation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Immune Checkpoint Modulators | Anti-PD-1 (clone RMP1-14), Anti-CTLA-4 (clone 9D9), Anti-PD-L1 (clone 10F.9G2) | In vivo therapeutic studies, Mechanism of action research | Block inhibitory signals to enhance T cell function |

| Cytokine Detection | LEGENDplex panels, ELISA kits for IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-2, IL-6 | Immune monitoring, T cell functionality assessment | Quantify immune activation and inflammatory responses |

| Cell Tracking Dyes | CFSE, CellTrace Violet, PKH26 | Proliferation assays, Adoptive transfer studies | Monitor cell division and migration in vivo and in vitro |

| MHC Multimers | PE- or APC-conjugated tetramers, dextramers | Antigen-specific T cell detection | Identify and isolate T cells with specific antigen specificity |

| Intracellular Staining Kits | FoxP3/Transcription Factor Staining Buffer Set | T cell differentiation and exhaustion analysis | Characterize T cell subsets and functional states |

| Animal Models | C57BL/6, BALB/c mice, MC38, B16F10, 4T1 tumor models | Preclinical efficacy studies, Tumor-immune interactions | Provide physiologically relevant systems for immunotherapy research |

The cancer-immunity cycle provides an essential framework for understanding the sequential events required for effective anti-tumor immunity and for developing strategies to overcome rate-limiting steps. Recent advances have refined our understanding of this cycle, including the evolving mechanisms of checkpoint inhibition, the role of dendritic cells in sustaining anti-tumor immunity, and the complex dynamics of the tumor microenvironment [2]. The integration of quantitative modeling approaches with experimental immunology has enabled more precise investigation of these dynamics and improved prediction of treatment outcomes [7].

Future research directions should focus on overcoming persistent challenges including tumor heterogeneity, immunosuppressive microenvironments, and acquired resistance mechanisms [3]. Novel approaches such as multi-epitope vaccines targeting conserved antigens, personalized vaccines incorporating patient-specific neoantigens, and innovative delivery systems designed to enhance lymph node targeting and antigen presentation show particular promise [3]. The convergence of artificial intelligence, systems immunology, and advanced manufacturing technologies will likely accelerate vaccine development and enable truly personalized cancer immunotherapy tailored to individual patients' immune profiles and tumor characteristics [3].

As the field advances, the cancer-immunity cycle will continue to serve as a fundamental conceptual framework for understanding and manipulating anti-tumor immune responses, guiding the development of next-generation immunotherapies with enhanced efficacy and reduced toxicity.

Immune checkpoint pathways, particularly cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4) and programmed death protein 1 (PD-1) and its ligand (PD-L1), constitute critical regulatory mechanisms that maintain immune homeostasis and prevent autoimmunity. In the tumor microenvironment, cancer cells exploit these pathways to evade immune surveillance, facilitating tumor progression. This technical review examines the molecular biology of CTLA-4 and PD-1/PD-L1 signaling, their distinct and complementary roles in immune regulation, and the mechanisms by which their inhibition generates antitumor immunity. We further analyze the experimental methodologies essential for investigating these pathways and summarize quantitative data on therapeutic efficacy and immune-related adverse events. Understanding these mechanisms provides the foundation for developing more effective immunotherapeutic strategies against cancer.

The adaptive immune system employs multiple checkpoint pathways to regulate the intensity and duration of immune responses, thereby maintaining self-tolerance and preventing autoimmunity. Among these, the CTLA-4 and PD-1/PD-L1 pathways represent two distinct but complementary mechanisms that negatively regulate T-cell activation and function at different stages of the immune response [9]. CTLA-4 primarily regulates the early phase of T-cell activation in lymphoid organs, while PD-1 modulates effector T-cell activity in peripheral tissues, particularly in the tumor microenvironment [9]. Malignant cells co-opt these inhibitory pathways to evade immune destruction, making them prime targets for cancer immunotherapy. Blockade of these checkpoints with monoclonal antibodies has demonstrated remarkable clinical efficacy across multiple cancer types, revolutionizing cancer treatment [10] [11]. This whitepaper provides a comprehensive technical analysis of the biology, signaling mechanisms, and therapeutic targeting of these critical immune checkpoint pathways within the broader context of antitumor immunity and treatment-related toxicity.

Molecular Biology of CTLA-4

Gene Structure and Protein Isoforms

The CTLA-4 gene is located on chromosome 2 in humans and consists of four exons [12]. Exon 1 encodes the leader peptide, exon 2 contains the ligand-binding domain, exon 3 comprises the transmembrane domain, and exon 4 encodes the cytoplasmic tail [13]. Alternative splicing generates multiple CTLA-4 isoforms:

- Full-length CTLA-4 (flCTLA-4): Contains all four exons and represents the membrane-bound form [12]

- Soluble CTLA-4 (sCTLA-4): Lacks exon 3 and is detectable in serum [13]

- Ligand-independent CTLA-4 (liCTLA-4): An murine-specific isoform containing exons 1, 3, and 4 [12]

In resting T-cells, CTLA-4 is predominantly localized in intracellular vesicles, with only minimal surface expression. Upon T-cell receptor (TCR) engagement, CTLA-4 rapidly translocates to the cell surface via exocytosis of CTLA-4-containing vesicles, a process regulated by TCR signaling strength in a graded feedback mechanism [9].

Expression and Regulation

CTLA-4 expression is primarily induced by T-cell activation, with detectable mRNA appearing within 1 hour of TCR ligation and peaking at 24-36 hours post-activation [13]. The transcription factor NF-AT plays a crucial role in CTLA-4 transcription, as inhibition of NF-AT activity significantly reduces CTLA-4 protein expression [13]. The intracellular trafficking and surface expression of CTLA-4 are tightly regulated by multiple mechanisms:

- Externalization: Mediated by TRIM (T-cell receptor interacting molecule) in the trans-Golgi network, GTPase ARF-1, phospholipase D, calcium influx, and Rab11 [13]

- Internalization: Occurs through both clathrin-dependent (via adaptor proteins CAP-1 and CAP-2) and clathrin-independent (via dynamin) pathways [13]

- Degradation: CTLA-4 binds with CAP-1 in the Golgi apparatus and is transported to lysosomal compartments for degradation [13]

Regulatory T cells (Tregs) constitutively express CTLA-4, which is essential for their suppressive function [12]. Genetic deletion of CTLA-4 in Tregs impairs their ability to suppress immune responses, leading to massive lymphoproliferation and fatal autoimmune disease [12] [9].

Signaling Mechanisms

CTLA-4 functions primarily as a competitive inhibitor of the co-stimulatory receptor CD28. Both molecules share the same ligands, CD80 (B7-1) and CD86 (B7-2), but CTLA-4 binds with significantly higher affinity and avidity [9]. The inhibitory function of CTLA-4 is mediated through several distinct mechanisms:

- Ligand Competition: CTLA-4 outcompetes CD28 for binding to CD80/CD86, thereby preventing CD28-mediated co-stimulation [9]

- Signal Inhibition: CTLA-4 engagement generates intracellular signals that actively inhibit T-cell activation by dephosphorylating key TCR signaling components, including CD3ζ and ZAP70 [13]

- Ligand Transendocytosis: CTLA-4 on Tregs physically removes CD80/CD86 from antigen-presenting cells through trans-endocytosis, thereby reducing the availability of co-stimulatory ligands for CD28 on effector T-cells [12]

- Metabolic Regulation: CTLA-4 signaling inhibits Akt phosphorylation and activation, negatively regulating cell cycle progression and T-cell proliferation [13]

The following diagram illustrates CTLA-4 signaling and its inhibitory effects on T-cell activation:

Figure 1: CTLA-4 Signaling Pathway. CTLA-4 competes with CD28 for binding to B7 molecules on antigen-presenting cells (APCs), generating inhibitory signals that counteract T-cell receptor (TCR) and CD28-mediated activation.

Molecular Biology of PD-1/PD-L1

Gene Structure and Expression

PD-1 (programmed death protein 1, CD279) is a 55-kDa transmembrane protein belonging to the CD28/CTLA-4 superfamily [14]. The PD-1 gene encodes a 288-amino acid protein consisting of an extracellular IgV-like domain, a transmembrane domain, and a cytoplasmic tail containing both an immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motif (ITIM) and an immunoreceptor tyrosine-based switch motif (ITSM) [14] [15]. PD-1 expression is induced on T cells, B cells, natural killer (NK) cells, monocytes, and dendritic cells upon activation [14]. The transcription of PD-1 is regulated by multiple transcription factors, including NFAT, NOTCH, FOXO1, and IRF9, which bind to conserved regulatory regions in the PD-1 promoter [14].

PD-L1 (programmed death ligand 1, B7-H1, CD274) is a 33-kDa type I transmembrane glycoprotein containing 290 amino acids with Ig-like and IgC-like domains in its extracellular region [14]. PD-L1 is constitutively expressed on macrophages, dendritic cells, and some epithelial cells, and its expression can be induced by inflammatory cytokines, particularly interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), through the JAK/STAT signaling pathway [14] [10]. In the tumor microenvironment, multiple cancer types exploit this pathway by upregulating PD-L1 expression as an "adaptive immune resistance" mechanism [14].

Signaling Mechanisms

The PD-1/PD-L1 axis suppresses T-cell function through multiple intricate signaling pathways:

SHP2-Mediated Dephosphorylation: Upon PD-1 binding to PD-L1, phosphorylation of tyrosine residues in the ITSM and ITIM motifs recruits the tyrosine phosphatase SHP2 [15]. Activated SHP2 dephosphorylates key signaling molecules in the TCR pathway, including CD3ζ, ZAP70, and PKCθ, thereby attenuating TCR signal transduction [15]

PI3K/AKT Pathway Inhibition: PD-1 signaling enhances PTEN phosphatase activity by inhibiting casein kinase 2 (CK2)-mediated phosphorylation of PTEN [16]. Active PTEN dephosphorylates PIP3 to PIP2, reducing PIP3 availability and consequently inhibiting PI3K/AKT pathway activation, which is crucial for T-cell survival, metabolism, and proliferation [16]

Ras/MEK/ERK Pathway Inhibition: PD-1 suppresses the activation of the Ras/MEK/ERK pathway by inhibiting PLCγ1 activation, thereby reducing diacylglycerol (DAG) production and calcium influx, ultimately impairing T-cell proliferation and differentiation [16]

Metabolic Reprogramming: PD-1 signaling inhibits glycolysis and promotes fatty acid oxidation, shifting T-cell metabolism toward a state of energy conservation that is incompatible with robust effector function [15]

Transcriptional Regulation: Chronic PD-1 signaling induces epigenetic modifications that stabilize the exhausted T-cell phenotype, characterized by reduced production of effector cytokines (IL-2, TNF-α, IFN-γ) and impaired cytolytic function [9]

The following diagram illustrates the intracellular signaling mechanisms of the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway:

Figure 2: PD-1/PD-L1 Intracellular Signaling. PD-1 engagement recruits SHP2, which dephosphorylates key TCR signaling components. Concurrently, PD-1 signaling activates PTEN and inhibits PLCγ1, suppressing both PI3K/AKT and Ras/MEK/ERK pathways, ultimately leading to T-cell exhaustion.

Comparative Analysis of CTLA-4 and PD-1/PD-L1 Pathways

While both CTLA-4 and PD-1 function as inhibitory immune checkpoints, they regulate distinct phases of immune responses through different mechanisms. The table below summarizes the key differences between these two critical pathways:

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of CTLA-4 and PD-1/PD-L1 Pathways

| Parameter | CTLA-4 Pathway | PD-1/PD-L1 Pathway |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Function | Regulates early T-cell activation in lymphoid organs | Modulates effector T-cell function in peripheral tissues |

| Expression Pattern | Primarily on activated T cells and constitutively on Tregs | On activated T cells, B cells, NK cells, monocytes, and DCs |

| Main Ligands | CD80 (B7-1), CD86 (B7-2) | PD-L1 (B7-H1), PD-L2 (B7-DC) |

| Binding Affinity | Higher affinity for CD80/CD86 than CD28 | High affinity for both PD-L1 and PD-L2 |

| Primary Mechanism | Competes with CD28 for ligands; transendocytosis | Transduces inhibitory signals via SHP2 phosphorylation |

| Key Signaling Pathways | Inhibition of ZAP70, CD3ζ; reduced AKT activation | Inhibition of PI3K/AKT and Ras/MEK/ERK via SHP2 |

| Role in Cancer | Limits initial T-cell activation against tumor antigens | Mediates T-cell exhaustion in tumor microenvironment |

| Therapeutic Targeting | Ipilimumab (anti-CTLA-4) | Nivolumab, Pembrolizumab (anti-PD-1); Atezolizumab (anti-PD-L1) |

Therapeutic Targeting in Cancer Immunotherapy

Mechanism of Antitumor Activity

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) function by blocking the interaction between inhibitory receptors and their ligands, thereby restoring T-cell-mediated antitumor immunity. The mechanisms of action differ between CTLA-4 and PD-1/PD-L1 blockade:

CTLA-4 Inhibition:

- Enhances priming and activation of tumor-specific T cells in lymph nodes [9]

- Increases the T-cell receptor diversity and repertoire [11]

- Reduces Treg-mediated suppression in the tumor microenvironment through Fc receptor-dependent depletion of intratumoral Tregs [11]

- Promotes clonal expansion of tumor-reactive T cells [9]

PD-1/PD-L1 Inhibition:

- Reverses T-cell exhaustion in the tumor microenvironment [15]

- Restores cytokine production (IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-2) and cytotoxic function of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes [14]

- Reactivates antigen-experienced T cells that have become dysfunctional [9]

- Enhances T-cell survival and metabolic fitness within tumors [15]

Dual Blockade: Combined CTLA-4 and PD-1/PD-L1 inhibition produces synergistic antitumor effects through complementary mechanisms. CTLA-4 blockade expands the T-cell repertoire during priming, while PD-1/PD-L1 blockade reverses exhaustion in the effector phase [11]. This combination has demonstrated superior efficacy in multiple cancer types, including melanoma and non-small cell lung cancer, albeit with increased immune-related adverse events [11].

Quantitative Clinical Data

Table 2: Clinical Efficacy of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Selected Cancers

| Therapy | Cancer Type | Objective Response Rate (%) | Overall Survival (Months) | Grade 3-5 Adverse Events (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ipilimumab (anti-CTLA-4) | Melanoma | 10.9-15.2 | 10.0-11.4 | 19.9-27.3 |

| Nivolumab (anti-PD-1) | Melanoma | 31.7-44 | 25.5-37.5 | 15.0-21.8 |

| Pembrolizumab (anti-PD-1) | NSCLC | 19.4-44.8 | 10.4-30.0 | 9.5-16.5 |

| Nivolumab + Ipilimumab | Melanoma | 50-58 | 36.9-Not Reached | 55.0-59.0 |

| Nivolumab + Ipilimumab | NSCLC | 35.9-43.7 | 17.1-Not Reached | 31.0-36.4 |

Table 3: Incidence of Immune-Related Adverse Events (irAEs) with Checkpoint Inhibitors

| Adverse Event | Anti-CTLA-4 (%) | Anti-PD-1/PD-L1 (%) | Combination Therapy (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any Grade irAE | 72.1-88.9 | 66.1-74.1 | 89.9-95.1 |

| Colitis/Diarrhea | 8.3-36.3 | 1.5-2.9 | 9.4-13.6 |

| Hepatitis | 1.5-10.0 | 0.7-3.6 | 11.0-15.0 |

| Pneumonitis | 0.0-1.5 | 1.6-4.1 | 4.4-7.0 |

| Rash | 15.2-30.3 | 9.3-19.6 | 21.1-30.5 |

| Endocrinopathies | 4.3-10.0 | 4.1-10.6 | 7.6-13.0 |

Experimental Methodologies

Key Research Protocols

In Vitro T-cell Activation and Inhibition Assays:

- T-cell Stimulation: Isolate human PBMCs or mouse splenocytes and activate with anti-CD3/CD28 antibodies (1-5 μg/mL) for 24-72 hours [12]

- Checkpoint Blockade: Add anti-CTLA-4 (10 μg/mL) or anti-PD-1/PD-L1 (5-10 μg/mL) antibodies to cultures

- Proliferation Measurement: Assess using 3H-thymidine incorporation or CFSE dilution by flow cytometry [12]

- Cytokine Analysis: Quantify IL-2, IFN-γ, TNF-α in supernatants by ELISA or multiplex immunoassay

- Signaling Analysis: Perform Western blotting for phosphorylated AKT, ERK, ZAP70, and SHP2

Mixed Lymphocyte Reaction (MLR):

- Stimulator Cells: Irradiate (30 Gy) allogeneic PBMCs or dendritic cells

- Responder Cells: Label with CFSE and co-culture with stimulators at 1:1 to 1:10 ratios

- Checkpoint Modulation: Add blocking antibodies or recombinant checkpoint proteins

- Analysis: Measure T-cell proliferation after 5-7 days by flow cytometry and cytokine production

Transendocytosis Assay (CTLA-4 Function):

- Cell Preparation: Generate CTLA-4-expressing cells (Tregs or transfected cells) and CD80-GFP-expressing APCs

- Co-culture: Incubate cells at 37°C for 2-4 hours

- Analysis: Quantify CD80-GFP internalization by flow cytometry or confocal microscopy [12]

T-cell Exhaustion Models:

- Chronic Stimulation: Repeatedly stimulate T cells with antigen or anti-CD3 weekly for 3-5 cycles

- Exhaustion Markers: Analyze PD-1, TIM-3, LAG-3 expression by flow cytometry

- Functional Assessment: Measure cytokine production (IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-2) and cytotoxic activity after restimulation

- Rescue Experiments: Test PD-1/PD-L1 blockade during later stimulation cycles

In Vivo Tumor Models

Syngeneic Mouse Models:

- Tumor Inoculation: Implant 5×10^5 to 1×10^6 syngeneic tumor cells (B16-F10 melanoma, MC38 colon carcinoma) subcutaneously

- Treatment Initiation: Begin checkpoint inhibitor therapy when tumors reach 50-100 mm³

- Dosing Regimen: Administer anti-CTLA-4 (100-200 μg), anti-PD-1/PD-L1 (100-200 μg), or combination intraperitoneally every 3-4 days for 3-4 doses

- Endpoint Measurements: Monitor tumor volume twice weekly and survival daily

- Immune Analysis: Harvest tumors and lymphoid organs for flow cytometry, immunohistochemistry, and cytokine analysis

Genetically Engineered Mouse Models (GEMMs):

- Model Selection: Utilize spontaneous tumor models (e.g., TRAMP for prostate cancer, KPC for pancreatic cancer)

- Treatment Schedule: Initiate therapy at defined tumor stages or ages

- Long-term Monitoring: Assess tumor development, immune infiltration, and treatment efficacy over time

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Immune Checkpoint Investigation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Blocking Antibodies | Anti-CTLA-4 (clone 9D9), Anti-PD-1 (clone RMP1-14), Anti-PD-L1 (clone 10F.9G2) | In vitro and in vivo checkpoint blockade experiments |

| Recombinant Proteins | CTLA-4-Ig (Abatacept), PD-1-Fc, PD-L1-Fc | Ligand binding studies, inhibition assays |

| Reporters Systems | NFAT-luciferase, NF-κB-luciferase reporters | T-cell activation signaling measurement |

| Flow Cytometry Panels | Anti-CD3, CD4, CD8, CD25, CD44, CD62L, PD-1, CTLA-4, TIM-3, LAG-3 | Immune phenotyping and exhaustion marker analysis |

| Transgenic Models | CTLA-4 KO mice, PD-1 KO mice, huPD-1/huPD-L1 knock-in mice | Genetic function studies, humanized therapy testing |

| Signal Transduction Assays | Phospho-specific antibodies for ZAP70, AKT, ERK, SHP2 | Intracellular signaling pathway analysis |

The CTLA-4 and PD-1/PD-L1 pathways represent fundamental regulatory mechanisms that maintain immune homeostasis while serving as critical barriers to effective antitumor immunity. Understanding their distinct yet complementary biology has enabled the development of revolutionary cancer immunotherapies that have transformed treatment paradigms across multiple malignancies. Current research continues to elucidate the intricate molecular signaling events downstream of these receptors, their complex regulation at genetic, epigenetic, and post-translational levels, and their interactions with other immune modulators in the tumor microenvironment.

Future investigations should focus on several key areas: (1) identifying predictive biomarkers to optimize patient selection for monotherapy versus combination approaches; (2) developing strategies to overcome resistance to checkpoint inhibition; (3) elucidating the mechanisms underlying immune-related adverse events to improve therapeutic indices; and (4) designing novel therapeutic modalities such as bispecific antibodies that simultaneously target multiple checkpoints with reduced toxicity. As our understanding of these pathways deepens, so too will our ability to harness the immune system against cancer while maintaining the delicate balance of immune homeostasis.

The tumor microenvironment (TME) is a complex ecosystem that constitutes a major barrier to effective anti-tumor immunity and immunotherapy. This whitepaper delineates the primary mechanisms—cellular, molecular, and metabolic—through which the TME orchestrates immune evasion. We synthesize current research on stromal cell-mediated suppression, immune checkpoint dysregulation, and novel processes such as mitochondrial transfer. Furthermore, we provide a detailed experimental methodology for quantifying immunotherapy response, integrating multiparametric MRI and immunohistochemical validation. Designed for researchers and drug development professionals, this guide includes structured data, pathway visualizations, and a catalog of essential research reagents to facilitate the development of novel therapeutic strategies aimed at overcoming the immunosuppressive TME.

The tumor microenvironment (TME) is a dynamic and heterogeneous milieu composed of tumor cells, immune cells, stromal cells, vasculature, and extracellular matrix (ECM) that collectively play a decisive role in tumor initiation, progression, and resistance to therapy [17] [18]. Immune evasion within this ecosystem has emerged as a critical hallmark of cancer, enabling tumors to circumvent host immune surveillance and resist immunotherapeutic interventions [19]. The clinical significance of the TME is underscored by the limitations of current immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), which, despite revolutionizing cancer care, yield durable responses only in a subset of patients [17] [20]. A comprehensive understanding of the TME's immunosuppressive mechanisms is therefore paramount for advancing precision oncology and developing effective combination therapies.

The TME fosters immunosuppression through a multifaceted network of interacting components. These include metabolic reprogramming that starves immune cells of essential nutrients; stromal cell-driven immune dysfunction; epigenetic remodeling that fosters immune tolerance; and the dysregulation of critical immune checkpoint pathways [17] [19]. Recent breakthroughs, such as the discovery of mitochondrial transfer from cancer cells to T cells, reveal previously unknown dimensions of tumor-induced immune suppression [20]. This in-depth technical guide will systematically dissect these barriers to effective immunity, providing a framework for researchers and drug development professionals to identify and target the TME's most vulnerabilities.

Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms of Immune Evasion

Stromal Cell-Mediated Immunosuppression

Stromal cells, particularly cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), are the most abundant non-immune cellular components of the TME and are critical accomplices in tumor progression and immune evasion [21] [18]. CAFs originate from various sources, including resident fibroblasts, mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), and endothelial cells, through transdifferentiation induced by tumor-derived factors such as TGF-β, PDGF, and FGF-2 [18]. They contribute to immunosuppression through several mechanisms:

- Secretion of Immunosuppressive Mediators: CAFs secrete a plethora of cytokines and chemokines, including CXCL12, which can directly exclude T cells from the tumor periphery, creating an "immune-excluded" phenotype [17] [21]. They also produce TGF-β, which drives the differentiation of regulatory T cells (Tregs) and confers CD8+ T cells with a stem-like exhausted epigenetic state [17].

- Metabolic Interference: CAFs contribute to metabolic reprogramming by expressing CD39/CD73 ectoenzymes, which catalyze the conversion of extracellular ATP to immunosuppressive adenosine, thereby blunting T cell activation [17].

- Extracellular Matrix Remodeling: CAFs deposit and cross-link ECM components, creating a physical barrier that impedes T cell infiltration and promotes a "immune desert" phenotype [17] [18]. This dense ECM also contributes to increased interstitial fluid pressure and impairs drug delivery.

The relationship between stromal cells and immune cells is complex. For instance, CAFs interact with tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) to enhance tumorigenesis. CAF-derived factors such as IL-6, GM-CSF, and M-CSF can recruit and polarize macrophages towards an M2-like, immunosuppressive phenotype [21]. These TAMs, in turn, produce IL-10 and VEGF, further contributing to an immunosuppressive and pro-angiogenic niche [17] [21].

Immune Checkpoint Dysregulation

Immune checkpoints are crucial regulatory molecules that maintain self-tolerance and prevent autoimmunity. Tumors co-opt these pathways to suppress T cell activity and evade immune destruction [17] [22]. The programmed death-1 (PD-1) receptor on T cells and its ligand (PD-L1) on tumor and stromal cells constitute a primary axis of immune suppression in the TME.

- PD-1/PD-L1 Axis: PD-L1 is overexpressed in approximately 50% of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) cases [17]. Engagement of PD-1 with PD-L1 transduces inhibitory signals that lead to T cell exhaustion, characterized by impaired effector function and proliferative capacity. Tumor cells can also release extracellular vesicles (EVs) containing PD-L1, which can systemically suppress T cell activity [17].

- CTLA-4 Pathway: Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4) is another critical checkpoint, expressed predominantly on T cells, that competes with the co-stimulatory molecule CD28 for binding to B7 molecules on antigen-presenting cells. This interaction inhibits early T cell activation in lymph nodes [22]. Antibodies blocking CTLA-4 (e.g., ipilimumab) have demonstrated clinical efficacy, particularly in combination with PD-1 inhibitors [23] [24].

- Spatial Heterogeneity: The expression of checkpoints is not uniform. Spatial proteomic analyses have revealed PD-L1 enrichment at the invasive front of tumors, particularly on cancer stem-like cells (CSCs), where they impair immune synapse formation and protect this critical cell population [17].

The following table summarizes key immune checkpoints and their roles in the TME:

Table 1: Key Immune Checkpoints in the Tumor Microenvironment

| Checkpoint Molecule | Primary Expression | Ligand(s) | Mechanism of Action in TME | Therapeutic Inhibitors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PD-1 | T cells | PD-L1, PD-L2 | Induces T cell exhaustion and anergy; suppresses cytokine production and cytotoxicity [17] [22]. | Pembrolizumab, Nivolumab, Cemiplimab [22] |

| PD-L1 | Tumor cells, APCs, Stromal cells | PD-1 | Binds PD-1 on T cells to inhibit anti-tumor activity; can be secreted via EVs for systemic suppression [17] [22]. | Atezolizumab, Avelumab, Durvalumab [22] |

| CTLA-4 | T cells (primarily at activation) | B7-1 (CD80), B7-2 (CD86) | Outcompetes CD28 for B7 binding, transducing inhibitory signals and dampening early T cell activation [23] [22]. | Ipilimumab, Tremelimumab [23] [22] |

| LAG-3 | T cells, NK cells | MHC Class II | Negatively regulates T cell proliferation and effector function; contributes to T cell exhaustion [22]. | Relatlimab (in combo with Nivolumab) [22] |

Metabolic Reprogramming and Nutrient Competition

The TME is often characterized by nutrient deprivation, hypoxia, and acidosis, conditions that tumor cells adapt to but which severely impair effector immune cell function [17] [19]. This metabolic reprogramming constitutes a fundamental mechanism of immune evasion.

- Glycolytic Competition and Acidosis: Tumor cells predominantly utilize glycolysis for energy, even in normoxic conditions (the Warburg effect). This high glycolytic flux consumes glucose, a critical nutrient for T cell effector functions, and results in the accumulation of lactic acid. Lactate-induced acidosis directly inhibits T cell activation, proliferation, and cytokine production, while simultaneously promoting the differentiation of immunosuppressive Tregs [17].

- Hypoxia: Hypoxic regions within tumors activate hypoxia-inducible factors (HIFs) in both tumor and stromal cells. HIF-1α activation can upregulate PD-L1 expression on tumor cells and adenosine production via CD39/CD73 on Tregs, further amplifying immune suppression [17].

- Amino Acid Depletion: Enzymes such as indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) and arginase 1 (ARG1) are often overexpressed in the TME by cells like MDSCs and TAMs. IDO catabolizes tryptophan, while ARG1 depletes L-arginine. The depletion of these essential amino acids impairs T cell receptor signaling and leads to T cell cell cycle arrest [17] [21].

A Novel Mechanism: Mitochondrial Transfer

A groundbreaking study published in Nature has uncovered a previously unknown mechanism of immune evasion: the transfer of mitochondria from cancer cells to T cells [20]. This process leads to metabolic sabotage and functional impairment of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs).

Experimental Workflow and Key Findings:

- Observation: Analysis of TILs from patient samples revealed that a subset harbored mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) mutations identical to those in the matched cancer cells, suggesting transfer [20].

- Mechanism Investigation: In vitro co-culture experiments demonstrated that mitochondria are transferred from cancer cells to T cells via two primary routes: direct cell-cell contact through tunnelling nanotubes (TNTs) and indirectly via small extracellular vesicles (EVs). The use of inhibitors like cytochalasin B (TNT inhibitor) and GW4869 (EV release inhibitor) confirmed the involvement of both pathways [20].

- Functional Consequence: The transferred mutant mitochondria, equipped with mitophagy-inhibitory molecules, evade degradation in the T cells. This leads to homoplasmic replacement of the T cell's endogenous mitochondria. The resultant mitochondrial dysfunction causes metabolic abnormalities, senescence, and defective memory formation in T cells, severely compromising their antitumor capacity [20].

- Clinical Correlation: The presence of shared mtDNA mutations in tumor tissue and TILs was associated with a poorer prognosis in patients with melanoma or non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors, highlighting its clinical relevance [20].

This mechanism reveals a sophisticated strategy where cancer cells directly compromise the cellular energetics of attacking T cells.

Quantitative Assessment of the TME and Immunotherapy Response

Accurate assessment of the TME and early response to immunotherapy is critical for both basic research and clinical translation. Conventional anatomical imaging often fails to distinguish true progression from pseudoprogression. The following section details a multiparametric MRI (mpMRI) protocol for quantitative response assessment in a pre-clinical model, validated by ex vivo immunohistochemistry [24].

Experimental Protocol: mpMRI in a Murine Melanoma Model

Objective: To assess early response to combined anti-PD-L1 and anti-CTLA-4 immunotherapy using quantitative mpMRI features with ex vivo immunohistochemical validation [24].

Materials and Methods:

- Animal Model: Subcutaneous inoculation of B16-F10 murine melanoma cells into C57BL/6 mice (n=28). Randomization into therapy (n=14) and control (n=14) groups [24].

- Therapy Regimen: The therapy group received intraperitoneal injections of anti-PD-L1 and anti-CTLA-4 antibodies (20 µg/kg) on days 7, 9, and 11 post-inoculation. The control group received a placebo [24].

- MRI Acquisition:

- Scanner: 3-T clinical MRI scanner.

- Timepoints: Baseline (day 7) and follow-up (day 12).

- Sequences:

- T1-weighted imaging: For tumor morphology and volume.

- Diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI): To assess cellularity. Apparent Diffusion Coefficient (ADC) maps were calculated.

- Dynamic Contrast-Enhanced (DCE)-MRI: To evaluate perfusion and vascular permeability. Parameters like plasma volume (PV) and plasma flow (PF) were derived via tracer-kinetic modeling [24].

- Ex Vivo Validation: A separate cohort (n=24) was used for immunohistochemical analysis of:

- CD8+ T cells: To quantify tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs).

- Ki-67: To assess tumor cell proliferation.

- TUNEL: To measure apoptosis.

- CD31+: To determine microvascular density [24].

Key Results and Interpretation: The following table synthesizes the quantitative findings from this study, demonstrating how mpMRI parameters correlate with immunological and pathological changes in the TME post-therapy.

Table 2: Quantitative mpMRI and Immunohistochemistry Findings in Immunotherapy Response [24]

| Parameter | Group | Baseline (Day 7) | Follow-up (Day 12) | Ex Vivo Validation (IHC) | Biological Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor Volume | Control | Volume V1 | Significant increase (p ≤ 0.004) | N/A | Uncontrolled tumor growth. |

| Immunotherapy | Volume V1 ~= Control | Significant increase (p ≤ 0.004); No difference vs. Control (p = 0.630) | N/A | Pseudoprogression: Initial increase not indicative of true progression. | |

| ADC (mm²/s) | Control | Value A1 | No significant change | N/A | Stable tumor cellularity. |

| Immunotherapy | Value A1 ~= Control | Significant decrease (p = 0.001) | Higher CD8+ TILs (p = 0.048) | Decreased ADC reflects increased cellularity due to robust infiltration of T cells, an early sign of efficacy. | |

| Plasma Flow / Volume | Immunotherapy | N/A | N/A | Lower microvascular density (CD31+) (p < 0.001) | Antiangiogenic effect of successful immunotherapy. |

| N/A (IHC only) | Immunotherapy | N/A | N/A | Higher TUNEL (p < 0.001); Lower Ki-67 (p < 0.001) | Increased tumor cell apoptosis and decreased proliferation confirm therapeutic efficacy. |

This integrated approach demonstrates that functional MRI parameters like ADC are more sensitive indicators of early immunological response than tumor volume alone, providing a non-invasive window into dynamic changes within the TME.

Visualizing Key Mechanisms and Workflows

The "Trinity" Network of Immune Evasion in HNSCC

This diagram illustrates the three interlinked core pathways that drive immune evasion, as proposed in recent literature [17].

Mitochondrial Transfer from Cancer Cell to T Cell

This flowchart details the novel immune evasion mechanism involving the transfer of mitochondria from cancer cells to T cells, leading to T cell dysfunction [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

The following table catalogs essential reagents and tools, derived from the cited experimental protocols, for investigating the TME and immune evasion mechanisms [24] [20].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for TME and Immune Evasion Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Category | Specific Example(s) | Research Application / Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors | Biologics | Anti-PD-L1 antibody, Anti-CTLA-4 antibody [24] | In vivo intervention to study the effects of checkpoint blockade on the TME and tumor growth. |

| Pathway Inhibitors | Small Molecules | Cytochalasin B, GW4869, Y-27632 [20] | Mechanistic studies: Inhibit TNT formation (Cytochalasin B), small EV release (GW4869), or large EV release (Y-27632). |

| Cell Line | In Vitro/In Vivo Model | B16-F10 murine melanoma cells [24] | Syngeneic mouse model for studying immunotherapy and TME dynamics in vivo. |

| Fluorescent Tags | Molecular Probe | MitoDsRed, MitoTracker Green [20] | Visualize and track mitochondrial transfer and dynamics in co-culture experiments. |

| Antibodies for IHC | Research Antibodies | Anti-CD8, Anti-Ki-67, Anti-CD31, TUNEL assay kit [24] | Ex vivo validation of immune cell infiltration, proliferation, angiogenesis, and apoptosis. |

| MRI Contrast Agent | Imaging Reagent | Gadobutrol (Gadovist) [24] | Contrast agent for DCE-MRI to assess tumor perfusion and vascular permeability. |

The tumor microenvironment is a formidable barrier to effective anti-tumor immunity, employing a diverse and synergistic arsenal of cellular, molecular, and metabolic strategies to suppress and evade immune attack. From the well-established roles of stromal cells and immune checkpoints to the emerging paradigm of mitochondrial transfer, understanding these mechanisms is critical for advancing cancer immunotherapy. The integration of advanced techniques, such as multiparametric MRI and single-cell sequencing, provides researchers with the tools to dissect this complexity quantitatively. Overcoming the immunosuppressive TME will require innovative multi-targeted approaches that simultaneously disrupt these interconnected pathways. The insights and methodologies detailed in this whitepaper provide a foundation for the development of next-generation immunotherapies aimed at reprogramming the TME from a barrier into a facilitator of durable anti-tumor immunity.

While T-cells, particularly CD8+ cytotoxic T-cells, have dominated the cancer immunotherapy landscape, the immune system deploys a broader arsenal of effector cells capable of recognizing and eliminating malignant cells. Innate immune cells—including Natural Killer (NK) cells, macrophages, and dendritic cells (DCs)—are pivotal regulators of antitumor immunity, serving as both direct cytotoxic effectors and crucial orchestrators of adaptive immune responses. Within the complex ecosystem of the tumor microenvironment (TME), these cells exhibit remarkable functional plasticity, dynamically shifting between states that either suppress or promote tumor growth based on contextual signals. Understanding their molecular mechanisms, functional states, and therapeutic potential is essential for developing next-generation immunotherapies that extend beyond current T-cell-centric approaches. This review synthesizes current knowledge on NK cells, macrophages, and DCs in antitumor immunity, framing their roles within the broader mechanisms of antitumor activity and toxicity in immunotherapy research.

Natural Killer Cells: Innate Sentinels of Tumor Surveillance

Biological Characteristics and Cytotoxic Mechanisms

Natural Killer cells are innate lymphoid cells characterized by their capacity to recognize and eliminate virally infected and malignantly transformed cells without prior sensitization, functioning independently of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) restrictions [25]. Human NK cells are broadly classified into two primary subsets based on CD56 expression density: the CD56dim population, which predominates in peripheral blood and mediates potent cytotoxicity, and the CD56bright subset, which excels at cytokine production and immunoregulation [25]. NK cell activation is governed by a delicate balance between activating and inhibitory signals received through an array of surface receptors [26] [25].

Table: NK Cell Receptors and Their Functions

| Receptor Category | Example Receptors | Ligands | Primary Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Activating Receptors | NKG2D, NKp30, NKp44, NKp46, CD16 | Stress-induced ligands (e.g., MICA/B), viral proteins, antibody Fc regions | Recognize altered self-cells; mediate direct killing and antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) |

| Inhibitory Receptors | KIR2DL, KIR3DL, NKG2A, PD-1, TIGIT | MHC class I molecules, PD-L1, CD155 | Prevent autoimmunity by sensing "self"; often dysregulated in TME leading to NK cell dysfunction |

NK cells employ four principal mechanisms to eliminate tumor cells [25]:

- Perforin/Granzyme Pathway: Upon activation, NK cells release perforin, which forms pores in the target cell membrane, facilitating the entry of granzyme proteases that initiate apoptosis.

- Death Receptor Pathway: Expression of FAS ligand (FASL) or TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) engages corresponding death receptors on target cells, triggering caspase-mediated apoptosis.

- Antibody-Dependent Cellular Cytotoxicity (ADCC): The CD16 (FcγRIIIa) receptor binds to the Fc portion of antibodies coating tumor cells, leading to targeted NK cell activation and killing.

- Cytokine Secretion: NK cells produce inflammatory cytokines such as IFN-γ and TNF-α, which exert direct antitumor effects and enhance adaptive immune responses.

Figure 1: Multifaceted cytotoxic mechanisms employed by NK cells against tumor targets.

NK Cell Dysfunction in the Tumor Microenvironment

Within the immunosuppressive TME, NK cells frequently exhibit functional impairment through multiple mechanisms [26]. Metabolic competition from rapidly proliferating tumor cells leads to nutrient deprivation, while inhibitory metabolites like adenosine accumulate. The TME drives metabolic reprogramming and epigenetic silencing of key NK cell effector genes, further dampening cytotoxicity [26]. Additionally, tumor cells often upregulate ligands for inhibitory receptors (e.g., PD-L1 binding to PD-1) while downregulating activating receptor ligands, tilting the balance toward inhibition [25]. These suppressive mechanisms collectively undermine NK cell surveillance and facilitate immune evasion.

NK Cell-Based Immunotherapy: Clinical Applications and Protocols

Several innovative approaches are being developed to harness NK cells for cancer therapy:

Adoptive NK Cell Transfer: This involves infusing ex vivo expanded and activated allogeneic NK cells. Clinical trials in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) have demonstrated complete response rates of 45-58% with haploidentical NK cells [25]. A standard protocol involves isolating NK cells from donor peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) using immunomagnetic selection (e.g., CD56+), followed by 14-day ex vivo expansion with cytokines (IL-2, IL-15), and infusion into preconditioned patients.

Chimeric Antigen Receptor NK (CAR-NK) Cells: CAR-NK cells are engineered to express synthetic receptors targeting tumor-associated antigens. In a landmark trial (NCT03056339), CD19-targeting CAR-NK cells achieved a 73% objective response rate in B-cell malignancies without inducing severe cytokine release syndrome [25]. The manufacturing process typically involves lentiviral/retroviral transduction or electroporation of NK cells with CAR constructs, followed by expansion and validation of cytotoxicity.

NK Cell Engagers and Checkpoint Blockade: Bispecific engager antibodies simultaneously bind NK cell activating receptors (e.g., CD16) and tumor antigens, redirecting NK cell cytotoxicity. Combination therapy with anti-PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies reverses NK cell exhaustion and has shown synergistic efficacy in solid tumors including non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and ovarian cancer [25].

Table: Clinical Outcomes of Selected NK Cell Immunotherapies

| Therapy Modality | Clinical Context | Efficacy Outcomes | Safety Profile |

|---|---|---|---|

| Haploidentical NK Cell Transfer | Relapsed/Refractory AML | 45-58% Complete Response (CR) | No graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) ≥ grade 3; manageable cytokine release syndrome (CRS) |

| CD19-CAR-NK Cells | B-cell Malignancies | 73% Objective Response Rate (ORR) | No CRS ≥ grade 3; minimal neurotoxicity |

| Cytokine-Induced Memory-like NK | Advanced AML | 50% CR in phase I trial | Transient cytopenias; no dose-limiting toxicities |

| Anti-PD-1 + NK Cell Infusion | NSCLC, Ovarian Cancer | Enhanced ORR vs. monotherapy | Well-tolerated; immune-related adverse events comparable to anti-PD-1 alone |

Tumor-Associated Macrophages: Dual Roles in Tumor Immunity

Macrophage Polarization States and Functions

Macrophages exhibit exceptional plasticity, dynamically shifting their functional phenotypes in response to local signals within the TME. The traditional classification distinguishes between M1 (pro-inflammatory, antitumor) and M2 (immunoregulatory, protumor) polarization states, though this represents a simplified spectrum rather than a fixed binary [27] [28].

M1 Macrophages: Classically activated by interferon-γ (IFN-γ) and microbial products like lipopolysaccharide (LPS), M1 macrophages express high levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-12, TNF-α), inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), and major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II molecules [28]. They mediate direct tumor cell cytotoxicity through reactive oxygen species and nitric oxide production, while also promoting Th1-type adaptive immune responses.

M2 Macrophages: Alternatively activated by IL-4, IL-13, IL-10, and transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β), M2 macrophages upregulate scavenger receptors (CD206, CD163), produce anti-inflammatory cytokines (IL-10, TGF-β), and secrete pro-angiogenic factors like vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) [27]. They facilitate tumor progression through multiple mechanisms: suppressing T and NK cell function, promoting angiogenesis, enhancing tissue remodeling and metastasis, and contributing to an immunosuppressive TME.

Figure 2: Macrophage polarization states in the tumor microenvironment.

Protumor Functions and Immune Suppression

Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) predominantly exhibit an M2-like phenotype and contribute to multiple hallmarks of cancer progression [27]. They secrete matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and other proteases that remodel the extracellular matrix, facilitating tumor invasion and metastasis. Through VEGF and other angiogenic factors, TAMs promote the formation of new blood vessels to support tumor growth. Additionally, M2 TAMs suppress antitumor immunity through multiple mechanisms: expression of immune checkpoint ligands (PD-L1), secretion of immunosuppressive cytokines (IL-10, TGF-β), recruitment of regulatory T cells (Tregs) via CCL22, and metabolic disruption through arginase-1-mediated depletion of L-arginine required for T cell function [27].

Therapeutic Targeting of TAMs

Current therapeutic strategies targeting TAMs focus on three main approaches [27]:

Depletion Strategies: CSF-1R inhibitors (e.g., pexidartinib) block the colony-stimulating factor-1 receptor signaling essential for TAM survival and differentiation, reducing TAM infiltration in tumors. CCL2 inhibitors interfere with monocyte recruitment to tumors.

Repolarization Approaches: Nanoparticle-based delivery systems can be used to load M1-polarizing agents (TLR agonists, IFN-γ, or CD40 agonists) that reprogram M2 TAMs toward an M1 phenotype with antitumor capabilities.

Phagocytosis Enhancement: CD47-blocking antibodies disrupt the "don't eat me" signal employed by tumor cells, thereby enhancing macrophage-mediated phagocytosis of tumors. Clinical protocols typically involve combination therapy with tumor-opsonizing antibodies.

Table: Key Research Reagents for Macrophage Studies

| Research Reagent | Category | Primary Function | Experimental Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recombinant CSF-1 | Cytokine | Promotes macrophage survival, proliferation, and differentiation | In vitro generation of bone marrow-derived macrophages; M2 polarization studies |

| Pexidartinib (PLX3397) | Small Molecule Inhibitor | Selective CSF-1R tyrosine kinase inhibitor | In vivo TAM depletion; combination therapy with chemotherapy/checkpoint inhibitors |

| Recombinant IL-4/IL-13 | Cytokines | Induce alternative M2 macrophage activation | In vitro M2 polarization models; study of protumor macrophage functions |

| Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) | TLR4 Agonist | Induces classical M1 macrophage activation | In vitro M1 polarization; study of proinflammatory macrophage responses |

| Anti-CD206 Antibody | Immunological Reagent | Binds mannose receptor (M2 marker) | Flow cytometry identification of M2 macrophages; immunohistochemistry for TAM quantification |

| Recombinant IFN-γ | Cytokine | Drives classical M1 macrophage activation | In vitro M1 polarization; macrophage-mediated tumor cell killing assays |

Dendritic Cells: Orchestrators of Antitumor Immunity

DC Subsets and Specialized Functions

Dendritic cells are professional antigen-presenting cells that bridge innate and adaptive immunity by capturing, processing, and presenting tumor antigens to T cells. The DC compartment comprises several functionally distinct subsets [29]:

Conventional DCs (cDCs): cDCs are specialized in antigen presentation and can be divided into two main subsets:

- cDC1s are defined by expression of CD141 (BDCA-3) in humans and XCR1, and depend on the transcription factor BATF3 for development. They excel at cross-presenting exogenous antigens on MHC class I to CD8+ T cells, making them essential for initiating antitumor cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) responses [29] [30].

- cDC2s express CD1c (BDCA-1) in humans and specialize in presenting antigens to CD4+ T cells via MHC class II, shaping helper T cell responses through Th1, Th2, or Th17 polarization [29].

Plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs): pDCs are characterized by high CD123 expression and specialize in producing massive amounts of type I interferons (IFN-α/β) in response to viral infections. Their role in cancer is complex, as they can either promote antitumor immunity or support immunosuppression through Treg expansion in different contexts [29].

Monocyte-Derived DCs (moDCs): moDCs are generated from circulating monocytes under inflammatory conditions and have been widely utilized in clinical DC vaccination protocols due to their accessibility and expandability ex vivo [29].

DC Dysfunction and Therapeutic Engineering

In the TME, DCs often exhibit functional impairment through multiple mechanisms, including reduced antigen uptake and presentation, altered maturation, and increased expression of immunosuppressive molecules like PD-L1 and IL-10 [29]. These dysfunctional states limit their ability to initiate effective antitumor T cell responses. To overcome these limitations, several engineering strategies are being developed:

Genetic Engineering: DC progenitors (DCPs) can be engineered to express immunostimulatory cytokines (e.g., IL-12) and specialized receptors that enhance tumor antigen uptake [30]. A recent innovative approach involves engineering DCPs to express extracellular vesicle-internalizing receptors (EVIRs) that bind to "bait" molecules (e.g., GD2 disialoganglioside) on cancer cells, forcing internalization of tumor-derived EVs and promoting cross-dressing with preformed MHC-peptide complexes [30].

Ex Vivo DC Vaccines: The established protocol involves isolating monocytes from patient blood via leukapheresis, differentiating them to moDCs with GM-CSF and IL-4 over 5-7 days, loading with tumor antigens (peptides, tumor lysates, or mRNA), and maturing with cytokine cocktails (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, PGE2) or TLR agonists before reinfusion [29].

Figure 3: Standardized workflow for manufacturing ex vivo dendritic cell vaccines.

Clinical Applications and Combination Strategies

DC-based immunotherapies have demonstrated clinical safety and immunogenicity across multiple cancer types. Sipuleucel-T, the first FDA-approved DC vaccine for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer, demonstrated improved overall survival, establishing the clinical feasibility of this approach [29]. Current research focuses on enhancing efficacy through combination strategies with immune checkpoint inhibitors (anti-PD-1/PD-L1), personalized neoantigen targeting, and in vivo DC targeting approaches that bypass complex ex vivo manufacturing [29]. Biomaterials-based delivery systems and artificial intelligence-driven epitope prediction are emerging technologies that promise to further improve DC vaccine efficacy [29].

Cross-Talk and Integrated Immune Responses

The antitumor immune response depends on sophisticated communication between innate and adaptive immune cells. DCs serve as critical integrators by capturing tumor antigens and presenting them to naïve T cells in lymph nodes, initiating antigen-specific responses [29]. NK cells contribute to this network by producing IFN-γ that enhances DC maturation and promotes Th1 differentiation, while also eliminating immunosuppressive cells and poorly immunogenic tumor variants [26] [25]. Activated T cells reciprocally enhance NK cell function through cytokine secretion and CD40L-CD40 interactions. Conversely, M2-polarized TAMs disrupt this productive cross-talk by secreting IL-10 and TGF-β that inhibit DC maturation and T cell priming, while also expressing PD-L1 that directly suppresses T and NK cell activity [27]. This complex cellular network highlights the importance of therapeutic strategies that simultaneously target multiple immune components to overcome immunosuppression and establish durable antitumor immunity.

NK cells, macrophages, and dendritic cells represent powerful effector populations whose therapeutic potential extends beyond current T-cell-centric approaches. Each cell type contributes unique mechanisms for tumor recognition and elimination, while their functional plasticity within the TME presents both challenges and opportunities for therapeutic intervention. Future progress will require strategies that overcome immunosuppressive mechanisms while enhancing the natural antitumor capabilities of these innate immune effectors. Promising directions include advanced cell engineering approaches (CAR-NK, EVIR-DC), targeted repolarization therapies (M2-to-M1 macrophage switching), and rational combination regimens that simultaneously engage multiple arms of the immune system. As our understanding of the complex interactions within the TME deepens, therapies harnessing the full spectrum of innate and adaptive immunity will likely yield more effective and durable responses against cancer.

The gut microbiome, a complex ecosystem of bacteria, fungi, viruses, and archaea, has emerged as a critical regulator of systemic immunity and a powerful modulator of cancer immunotherapy efficacy [31] [32]. Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), which block inhibitory pathways such as PD-1, PD-L1, and CTLA-4 to unleash antitumor immunity, have revolutionized oncology [33] [34]. However, only 20-40% of patients derive durable benefit, creating an urgent need to understand the factors driving treatment resistance [31] [35]. Accumulating clinical and preclinical evidence demonstrates that the composition and functional output of the gut microbiome significantly influence patient responses to ICIs and the incidence of immune-related adverse events (irAEs) [31] [36]. This review synthesizes current knowledge on the microbial species, metabolites, and mechanisms underlying this relationship, providing a technical guide for researchers and drug development professionals focused on optimizing cancer immunotherapy.

The Gut Microbiome as a Determinant of Immunotherapy Outcome

Clinical Evidence Linking Microbiome to ICI Response

The impact of the gut microbiome on ICI efficacy is observed across multiple cancer types. Clinical studies consistently show that patients responding to ICIs exhibit distinct gut microbial communities compared to non-responders [36]. A meta-analysis of 71 studies confirmed that baseline microbiota composition significantly associates with ICI efficacy, with a pooled relative risk of 1.29 for objective response rate [35]. Greater gut microbial diversity consistently correlates with improved progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) across melanoma, non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), and renal cell carcinoma (RCC) [31] [32].

Table 1: Microbial Taxa Associated with Improved ICI Response Across Cancers

| Cancer Type | Associated Microbial Taxa | ICI Type | Clinical Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Melanoma | Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Bifidobacterium longum, Collinsella aerofaciens, Enterococcus faecium [31] [36] | Anti-PD-1 | Improved response [31] |

| NSCLC | Akkermansia muciniphila, Alistipes spp., Ruminococcus spp., Eubacterium spp. [31] [36] | Anti-PD-1 | Improved PFS/OS [31] |

| RCC | Akkermansia muciniphila [31] | Anti-PD-1 | Improved response [31] |

| Hepatobiliary | Alistipes [37] | Anti-PD-1/PD-L1 | Positively correlated with survival [37] |

| Multiple Cancers | Ruminococcaceae, Lachnospiraceae [31] | Anti-PD-1/CTLA-4 | Improved response [31] |

Conversely, specific microbial patterns are associated with resistance to immunotherapy. In biliary tract cancer, increased abundance of Bacilli, Lactobacillales, and the metabolite Pyrrolidine correlates with poorer survival outcomes [37]. Importantly, antibiotic exposure within 30 days of ICI initiation consistently impairs therapeutic responses across tumor types, highlighting the functional role of an intact microbial community [31] [32].

Microbiome Influence on Adoptive Cell Therapies

The gut microbiome also modulates the efficacy of adoptive cell therapies (ACTs). Early studies demonstrated that broad-spectrum antibiotics like ciprofloxacin reduce ACT effectiveness in mice, an effect reversible by bacterial lipopolysaccharide supplementation that activates Toll-like receptor 4 pathways [31]. This suggests microbial components can directly stimulate innate immunity to enhance T-cell activity. While clinical data on microbiome-ACT interactions are less extensive than for ICIs, emerging evidence indicates that gut microbial composition influences chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR-T) therapy and other ACT outcomes [31].

Mechanisms of Microbiome-Mediated Immunomodulation

Microbial Metabolites as Key Immunomodulators

Microbiota-derived metabolites serve as crucial messengers between gut microbes and the host immune system, influencing anti-tumor immunity through multiple mechanisms.

Table 2: Key Microbiota-Derived Metabolites and Their Immunomodulatory Effects

| Metabolite Class | Representative Metabolites | Proposed Mechanisms in Immunotherapy | Impact on ICIs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) | Butyrate, Propionate, Acetate | Promote regulatory T-cell development; modulate dendritic cell activity; enhance CD8+ T-cell function [32] [38] | Context-dependent: Generally associated with improved response [32] |

| Bile acids | Secondary bile acids (deoxycholic acid, lithocholic acid) | Modulate Th1 and T-cell differentiation; enhance CD8+ T-cell function [31] [38] | Improved anti-tumor immunity [38] |

| Tryptophan derivatives | Indole-3-carbaldehyde, Kynurenine | Aryl hydrocarbon receptor activation; regulate immune cell function [34] [38] | Modulation of T-cell activity [38] |

| Inosine | - | Enhancement of T-cell activation and costimulation [32] | Improved anti-tumor response [32] |

| Polyamines | Spermidine, Spermine | Modulation of T-cell differentiation and function [38] | Under investigation [38] |

The immunomodulatory effects of these metabolites occur through several interconnected mechanisms: (1) direct interaction with immune cell receptors, (2) epigenetic modification of immune-related genes, and (3) alteration of cellular metabolism in both tumor and immune cells [38]. The net effect on immunotherapy outcomes depends on metabolite concentration, timing of exposure, and the local immune context.

Integrated Mechanisms of Microbiome-Mediated Antitumor Immunity

The gut microbiome influences multiple steps in the cancer-immunity cycle through diverse but interconnected mechanisms [39]. These include direct microbial stimulation of immune cells via pattern recognition receptors, metabolite-mediated epigenetic and functional reprogramming of immune cells, and molecular mimicry between microbial and tumor antigens that enhances T-cell cross-reactivity [31] [35]. The following diagram illustrates the key mechanisms through which the gut microbiome and its metabolites systemically influence antitumor immunity and response to immunotherapy.

Experimental Approaches for Microbiome-Immunotherapy Research

Standardized Workflow for Microbiome Analysis

Investigating the microbiome-ICI response relationship requires a structured pipeline from sample collection to data integration. The following workflow outlines key steps for robust microbiome analysis in immunotherapy studies.

Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies