Cancer Stem Cell Markers: Navigating Identification Challenges and Therapeutic Opportunities

This article provides a comprehensive overview for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on the critical role of Cancer Stem Cells (CSCs) in tumor persistence, relapse, and therapy resistance.

Cancer Stem Cell Markers: Navigating Identification Challenges and Therapeutic Opportunities

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on the critical role of Cancer Stem Cells (CSCs) in tumor persistence, relapse, and therapy resistance. It explores the foundational biology of CSCs, detailing key stemness markers and their origins. The content covers current methodological approaches for CSC identification and isolation, addresses significant challenges in the field such as marker heterogeneity and plasticity, and evaluates emerging validation strategies using advanced technologies like single-cell sequencing and genome-wide CRISPR screens. The review synthesizes these insights to discuss future therapeutic avenues and the movement towards personalized cancer medicine.

The Biology of Cancer Stem Cells: Origins, Markers, and Stemness Pathways

The cancer stem cell (CSC) niche represents a specialized, anatomically distinct microenvironment within tumors that is essential for maintaining CSC properties, including self-renewal capacity, clonal tumor initiation, and clonal long-term repopulation potential [1]. Analogous to niches that regulate normal stem cells, the CSC niche provides critical cues through cell-cell contacts, secreted factors, and physical interactions that preserve CSC phenotypic plasticity, protect CSCs from immune surveillance, and facilitate metastatic spread [1] [2]. This niche constitutes a fundamental component of the broader tumor microenvironment (TME), comprising various stromal elements including fibroblastic cells, immune cells, endothelial and perivascular cells, extracellular matrix (ECM) components, and intricate networks of cytokines and growth factors [1]. The bidirectional communication between CSCs and their niche creates a dynamic ecosystem that not only sustains tumor progression but also presents significant challenges for therapeutic interventions, as CSCs residing within these protective niches demonstrate remarkable resilience to conventional cancer treatments including immunotherapy [1] [2].

Cellular and Molecular Composition of the CSC Niche

The CSC niche is a complex, multi-faceted microenvironment composed of diverse cellular populations and molecular components that collectively support CSC maintenance and function.

Cellular Components

- Immune Cells: The niche contains various immune cell types that typically exhibit immunosuppressive properties. These include tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), and regulatory T cells (Tregs) [3] [2]. These cells create an immune-privileged sanctuary for CSCs by suppressing anti-tumor immune responses.

- Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts (CAFs): CAFs are key stromal cells that support CSCs through the secretion of growth factors, cytokines, and ECM components [3]. They actively participate in creating and maintaining the niche structure.

- Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs): MSCs can migrate to tumor sites and influence cancer progression through multiple mechanisms. They release various bioactive factors that influence CSC stemness, drug resistance, and phenotype maintenance [3]. In ovarian cancer, MSCs produce BMP4 and BMP2, thereby amplifying the CSC population [3].

- Endothelial and Perivascular Cells: These vascular components contribute to niche function by supporting CSC maintenance and participating in angiogenic processes [1].

Molecular Components

- Extracellular Matrix (ECM): The ECM provides structural support and biochemical signals that influence CSC behavior. It serves as a reservoir for growth factors and cytokines and modulates mechanotransduction pathways [1].

- Secreted Factors: The niche is rich in various signaling molecules including cytokines (e.g., IL-6, IL-8), chemokines, growth factors (e.g., VEGF, TGF-β), and metabolites that regulate CSC self-renewal and survival [3] [4]. These factors can be freely released or encapsulated in extracellular vesicles.

- Exosomes and Extracellular Vesicles (EVs): CSCs and niche cells release EVs that enable the transfer of biomolecular cargos between different cell types, facilitating intercellular communication and modulation of the TME [4].

Table 1: Key Cellular Constituents of the CSC Niche and Their Functions

| Cell Type | Primary Functions in CSC Niche | Representative Signaling Molecules |

|---|---|---|

| TAMs/MDSCs | Create immunosuppressive environment; promote CSC survival | IL-10, TGF-β, ARG1 [3] [2] |

| Tregs | Suppress antitumor immunity; inhibit T-cell function | IL-10, TGF-β, CTLA-4 [3] [2] |

| CAFs | ECM remodeling; secrete growth factors; metabolic support | HGF, CXCL12, TGF-β [3] [4] |

| MSCs | Enhance stemness; increase CSC population; metabolic modulation | BMP4, BMP2, exosomes [3] |

| Endothelial Cells | Vascular niche formation; promote CSC self-renewal | Notch ligands, EGF, Angiopoietins [1] |

Functional Dynamics: How the Niche Influences CSC Behavior

The CSC niche employs multiple mechanisms to maintain CSC stemness, promote therapy resistance, and facilitate immune evasion.

Maintenance of Stemness and Plasticity

The niche actively maintains CSC stemness through the provision of specific molecular signals that activate key developmental pathways. These include Wnt/β-catenin, Notch, and Hedgehog signaling pathways, which are crucial for regulating self-renewal and differentiation [4]. The concept of CSC plasticity—the dynamic ability of CSCs to transition between stem-like and differentiated states in response to external stimuli—is fundamentally regulated by niche-derived signals [2]. Under therapeutic pressure or environmental stressors, the niche can promote dedifferentiation of non-CSCs back into the CSC pool, contributing to tumor heterogeneity and therapeutic resistance [1] [3]. This plasticity represents a sophisticated adaptive mechanism that allows tumors to survive diverse therapeutic assaults.

Therapy Resistance and Immune Evasion

The niche provides a physical sanctuary that protects CSCs from conventional therapies and immune-mediated attack. CSCs within their niche employ multiple intrinsic and extrinsic mechanisms to evade immune surveillance:

- Immune Checkpoint Expression: CSCs frequently upregulate immune checkpoint proteins such as PD-L1, which binds to PD-1 on T cells, inhibiting their activation and function [2]. Other checkpoints including B7-H4, B7-H3, CD47, and CD24 are also utilized by CSCs to evade immune surveillance [2].

- Antigen Presentation Downregulation: CSCs often downregulate major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I molecules, reducing their visibility to cytotoxic T lymphocytes [2].

- Soluble Factor Secretion: CSCs and niche cells secrete immunosuppressive factors including TGF-β, IL-10, and prostaglandin E2 that actively dampen antitumor immune responses [2] [4].

- Metabolic Adaptations: CSCs exhibit metabolic plasticity, allowing them to switch between glycolysis, oxidative phosphorylation, and alternative fuel sources such as glutamine and fatty acids based on environmental conditions [5]. This adaptability enhances their survival under metabolic stress induced by therapies.

Table 2: CSC Immune Evasion Mechanisms Facilitated by the Niche

| Evasion Mechanism | Molecular Players | Functional Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Immune Checkpoint Upregulation | PD-L1, B7-H4, CD47, CD24 | Suppression of T-cell function; inhibition of phagocytosis [2] |

| Reduced Antigen Presentation | Downregulated MHC class I | Decreased recognition by cytotoxic T cells [2] |

| Immunosuppressive Secretome | TGF-β, IL-10, PGE2 | Recruitment of Tregs and MDSCs; T-cell inhibition [2] [4] |

| Metabolic Competition | Nutrient consumption; lactate secretion | Creation of metabolically hostile TME for immune cells [5] |

Experimental Approaches for CSC Niche Characterization

Advanced methodologies are required to dissect the complex architecture and function of the CSC niche.

Single-Cell and Spatial Analysis Technologies

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) enables the resolution of cellular heterogeneity within the CSC niche by providing transcriptomic profiles of individual cells [5] [6]. This approach has revealed significant differences in immune cell composition between extramedullary multiple myeloma TME and bone marrow counterparts, identifying T and NK cells as the most abundant immune subsets with distinct functional states [6]. Spatial transcriptomics complements scRNA-seq by preserving the geographical context of cellular interactions, allowing researchers to map the precise localization of CSCs within their niche [5] [6]. These technologies collectively facilitate the identification of unique gene expression patterns and cell-cell communication networks that define the niche.

Artificial Intelligence in TME Analysis

Artificial intelligence (AI) approaches are increasingly employed to characterize the TME and CSC niche from standard histopathological images. The HistoTME platform represents a novel weakly supervised deep learning approach that can infer TME composition directly from hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained histopathology images [7]. This method accurately predicts the expression of 30 distinct cell type-specific molecular signatures and can classify tumor microenvironments into immune phenotypes such as "Immune-Inflamed" and "Immune-Desert" with clinical relevance for predicting immunotherapy response [7].

AI-Based TME Analysis Workflow

CSC Marker Identification and Validation

The identification and validation of CSC markers within their native niche context remains challenging due to CSC heterogeneity and plasticity. Methodologies include:

- Multiple Immunohistochemistry: Simultaneous staining for multiple putative CSC markers (e.g., p75NTR, ALDH1A1, BMI1) enables the visualization of different CSC subpopulations and their spatial relationships within the niche [8]. This approach has revealed that multiple stem cell subpopulations with distinct phenotypes can co-exist within a tumor, each impacting different clinical parameters [8].

- Flow Cytometry and FACS: Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) allows for the isolation and functional characterization of CSC subpopulations based on surface marker expression [8]. Studies demonstrate that CSC subpopulations identified by different markers are dynamic populations capable of phenotypic switching, with p75NTR+ cells exhibiting higher expression of proliferative and self-renewal markers compared to ALDH1A1+ cells [8].

- 3D Organoid Models: Three-dimensional organoid cultures recapitulate key aspects of the CSC niche in vitro, enabling the investigation of CSC-stroma interactions in a more physiologically relevant context [5].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for CSC Niche Characterization

| Research Reagent | Primary Function | Experimental Application |

|---|---|---|

| Anti-p75NTR Antibody | CSC surface marker detection | IHC, Flow Cytometry for CSC identification [8] |

| Anti-ALDH1A1 Antibody | Intracellular CSC marker detection | IHC, identifies ALDH1A1+ CSC subpopulation [8] |

| Anti-BMI1 Antibody | Self-renewal marker detection | IHC, evaluation of CSC self-renewal capacity [8] |

| Anti-Ki67 Antibody | Proliferation marker detection | IHC, assessment of CSC proliferative status [8] |

| CD44, CD133 Antibodies | CSC surface marker detection | Flow Cytometry, CSC isolation and enrichment [5] [9] |

| CRISPR-based Screens | Functional genomics | Identification of essential niche factors [5] |

Signaling Pathways Governing CSC-Niche Interactions

The functional interplay between CSCs and their niche is mediated by evolutionarily conserved signaling pathways that regulate stemness, survival, and adaptation.

Core Stemness Pathways

- Wnt/β-catenin Signaling: The canonical Wnt pathway serves as a vital regulator of tumor cell plasticity [4]. Activation of this pathway enhances the expression of CSC surface markers and promotes self-renewal, while also contributing to immune evasion through positive feedback loops with PD-L1 expression [2] [4].

- Notch Signaling: The Notch pathway regulates stem cell differentiation and self-renewal, with aberrant signaling stimulating CSC self-renewal in various cancers including ovarian, breast, and hepatocellular carcinoma [4]. Epigenetic regulation through histone modifications further modulates NOTCH1 signaling in CSCs [4].

- Hedgehog Signaling: The Hedgehog pathway drives tumor growth, invasion, and recurrence following therapeutic intervention [4]. In colorectal cancer, cancer-initiating cells express the Indian hedgehog (IHH) gene, which contributes to their maintenance [4].

Integrin-Mediated Niche Interactions

Integrins function as critical mediators of CSC-niche adhesion and signaling. These heterodimeric cell surface receptors promote cell proliferation, differentiation, adhesion to ECM, and migration by sensing the cellular microenvironment [4]. Specific integrins have been implicated in CSC biology:

- Integrin α6: Strongly expressed in glioblastoma cells and used as a biomarker for CSC identification [4].

- Integrin αVβ3: Implicated in developing resistance to receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors in lung cancer [4].

- Integrin α3: Shows context-dependent functions, inhibiting metastasis in prostate cancer while promoting invasion in glioblastoma [4].

Signaling Pathways in CSC-Niche Crosstalk

Therapeutic Implications and Targeting Strategies

Targeting the CSC niche represents a promising therapeutic approach to overcome treatment resistance. Several strategies are under investigation:

- Dual Metabolic Inhibition: Targeting the metabolic plasticity of CSCs through combination approaches that simultaneously inhibit multiple metabolic pathways [5].

- Niche-Disrupting Agents: Therapeutic interventions aimed at disrupting the protective niche microenvironment, thereby sensitizing CSCs to conventional treatments [1] [10].

- Immune-Based Approaches: Engineering immune cells such as CAR-T cells to target CSC-specific markers, and developing immune checkpoint inhibitors specific to CSC-expressed checkpoints [5] [2].

- Synthetic Biology-Based Interventions: Utilizing advanced engineered systems to precisely target CSC-niche interactions [5].

The integrative targeting of both CSCs and their niche components holds significant promise for developing more effective cancer therapies that can overcome the formidable challenges posed by therapy resistance and tumor recurrence.

Cancer stem cells (CSCs) represent a subpopulation of tumor cells with unique self-renewal capacity, differentiation potential, and resistance to conventional therapies, driving tumor initiation, progression, metastasis, and recurrence [11]. The concept of CSCs has evolved significantly since its initial formulation, with contemporary research revealing complex origins and dynamic behavior. The cellular origin of CSCs remains a fundamental question in cancer biology, with compelling evidence indicating two primary sources: transformed tissue-resident stem cells or dedifferentiated mature cells that reacquire stem-like properties [12]. This cellular plasticity allows non-CSCs to regain stemness characteristics under specific environmental pressures, creating a dynamic hierarchy within tumors that complicates therapeutic targeting [5] [2]. Understanding these origins provides crucial insights into the molecular mechanisms driving tumor heterogeneity, therapy resistance, and disease recurrence, offering potential avenues for more effective cancer interventions that address the root sources of tumor propagation and resilience.

Dual Origin Theory of Cancer Stem Cells

The initiation of CSCs can follow two distinct pathways, each with implications for tumor behavior and therapeutic response. The transformation process involves overexpression of oncogenes and inactivation of tumor suppressors, leading to uncontrolled growth and the acquisition of stem cell characteristics [12].

Origin from Tissue-Resident Stem Cells

Tissue-resident stem cells, with their inherent self-renewal capabilities and prolonged lifespan, represent natural candidates for CSC transformation. These cells already possess the molecular machinery for unlimited proliferation, potentially requiring fewer genomic alterations for malignant transformation compared to differentiated cells [12]. Research across multiple cancer types supports this origin model:

- Gastric cancers: Slow-cycling Mist1-expressing cells in the gastric corpus and Lgr5-expressing cells in the gastric antrum have been identified as cells of origin [12].

- Squamous cell carcinomas: Basal stem cells in trachea and main bronchi self-renew and form heterogeneous spheres, potentially leading to hyperplasia and eventual squamous cell carcinoma [12].

- Hematological malignancies: In acute myeloid leukemia (AML), the cell of origin is typically a hematopoietic stem or progenitor cell, while in chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), it is characterized by Bcr-Abl oncogene expression in stem/progenitor cells [12].

The differentiation phenotype and aggressiveness of resulting tumors appear influenced by the specific tissue-resident stem cell population of origin. For example, in breast cancer, tumors originating from luminal progenitors are generally associated with better prognosis, while those from basal-like progenitors display more aggressive phenotypes [12].

Origin from Differentiated Cells via Dedifferentiation

Differentiated cells can undergo transformation into CSCs through dedifferentiation processes, regaining stem-like properties through genetic and epigenetic alterations:

- Colon cancers: Studies demonstrate that differentiated intestinal epithelial cells can potentially become CSCs under certain conditions [12].

- Liver cancer: Cell tracking studies show that hepatocytes (mature liver cells) can serve as cells of origin for liver cancer [12].

- Cellular plasticity: Non-CSCs can acquire stem-like features in response to environmental stimuli such as hypoxia, inflammation, or therapeutic pressure [5] [2].

This dedifferentiation process challenges the notion of a fixed CSC hierarchy and highlights the dynamic nature of stemness in cancer, representing a transient functional state rather than a static subpopulation [5].

Table 1: Comparative Features of CSC Origins Across Cancer Types

| Cancer Type | Tissue-Resident Stem Cell Origin | Differentiated Cell Origin | Key Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gastric Cancer | Mist1+ cells, Lgr5+ cells | Not specified | Mouse models showing stem cell transformation [12] |

| Colon Cancer | Not specified | Differentiated intestinal epithelial cells | Lineage tracing studies [12] |

| Liver Cancer | Hepatoblasts, hepatic progenitors | Adult hepatocytes | Cell tracking, in vivo studies [12] |

| Breast Cancer | Luminal progenitors, basal-like progenitors | Not specified | Association with differentiation phenotypes [12] |

| Leukemia | Hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells | Lymphoid progenitors (in some AML) | Expression profiling, transplantation models [12] |

Molecular Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways in CSC Biology

CSCs utilize complex molecular pathways to maintain their stemness properties and survival advantages. Understanding these mechanisms is crucial for developing targeted therapeutic approaches.

Core Stemness Signaling Pathways

Multiple evolutionarily conserved signaling pathways play pivotal roles in regulating CSC self-renewal, differentiation, and survival:

- Wnt/β-catenin signaling: Regulates CSC maintenance and interacts with immune checkpoint proteins like PD-L1, creating feedback loops that enhance both stemness and immune evasion [2] [11].

- Hedgehog signaling: Contributes to CSC self-renewal and tissue patterning, often dysregulated in various cancers [11].

- Notch signaling: Mediates cell-cell communication and fate decisions, maintaining CSC populations in multiple cancer types [11].

- JAK/STAT pathway: Particularly STAT3 activation, promotes survival and proliferation of CSCs [11].

- TGF-β/SMAD signaling: Regulates epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and stemness acquisition [11].

- PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway: Integrates metabolic and growth signals to support CSC survival under stress conditions [11].

These pathways form interconnected networks that sustain CSC populations and create therapeutic resistance. Their plasticity allows CSCs to adapt to therapeutic pressure and environmental changes, maintaining tumor propagating capacity despite targeted interventions [5] [11].

Metabolic Adaptations of CSCs

CSCs exhibit remarkable metabolic plasticity that enables survival under diverse environmental conditions. This adaptability represents a key mechanism of therapy resistance:

- Metabolic flexibility: CSCs can switch between glycolysis, oxidative phosphorylation, and alternative fuel sources such as glutamine and fatty acids depending on environmental conditions [5].

- Lip metabolism adaptations: Alterations in fatty acid oxidation (FAO) and lipogenesis support CSC resilience under stress [11].

- Metabolic symbiosis: Interactions with stromal cells, immune components, and vascular endothelial cells facilitate metabolic cooperation that promotes CSC survival [5].

This metabolic plasticity allows CSCs to persist despite therapies that target specific metabolic pathways, making them a persistent reservoir for tumor recurrence [5].

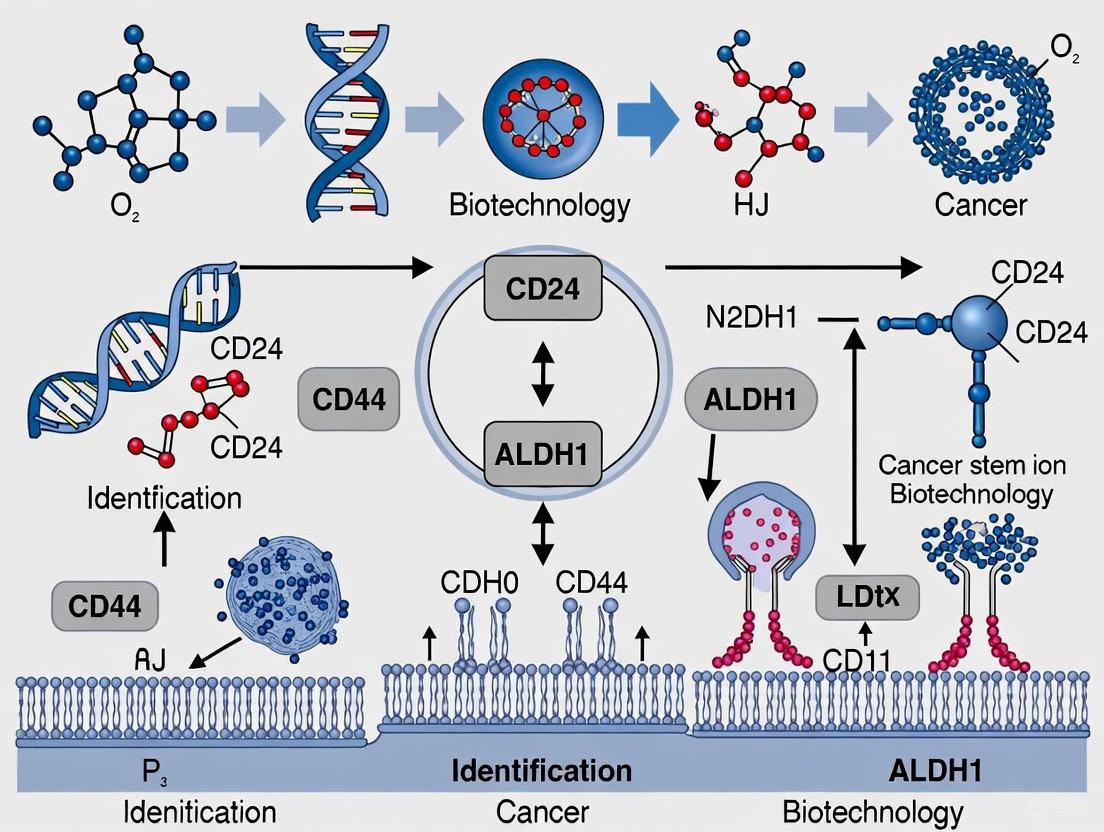

Diagram 1: CSC Origins and Signaling Pathways. This diagram illustrates the dual origins of CSCs and the core signaling pathways that maintain their stemness properties.

CSC Markers and Identification Challenges

The reliable identification and isolation of CSCs remains a significant challenge in cancer research due to marker heterogeneity and dynamic expression patterns.

Established and Emerging CSC Markers

Several cell surface proteins and functional markers have been employed to identify and isolate CSC populations across different cancer types:

- CD44: A hyaluronic acid receptor widely used as a CSC marker in multiple cancers including breast, pancreatic, and head and neck cancers [5] [11].

- CD133 (Prominin-1): A transmembrane glycoprotein marking CSC populations in glioblastoma, colon cancer, and others [5] [11].

- ALDH1 (Aldehyde Dehydrogenase 1): An intracellular detoxifying enzyme with high activity in CSCs of various cancers, detected via Aldefluor assay [8] [11].

- EpCAM (Epithelial Cell Adhesion Molecule): Used as a CSC marker in prostate and gastrointestinal cancers [5].

- CD24: Functions as an immune checkpoint by binding Siglec-10 on macrophages while also serving as a CSC marker [2].

- CD47: A "don't eat me" signal molecule upregulated in leukemia and other CSCs to evade phagocytosis [2].

These markers are often used in combination to enrich for CSC populations, though their expression varies significantly across cancer types and even within individual tumors [5] [8].

Challenges in CSC Marker Interpretation

Several critical challenges complicate the use of these markers for CSC identification:

- Lack of universal markers: No single marker is exclusively expressed by CSCs across different cancer types, and marker expression patterns are influenced by tissue origin and microenvironmental context [5].

- Marker heterogeneity: Multiple stem cell subpopulations with distinct phenotypes can coexist within a single tumor, each impacting different clinical parameters [8].

- Dynamic plasticity: CSC subpopulations identified by different markers represent dynamic populations capable of switching phenotypes over time [8].

- Non-specificity: Most markers expressed in CSCs are also found in normal stem cells or non-tumorigenic cancer cells, complicating specific targeting [5] [12].

Table 2: Common CSC Markers Across Cancer Types and Their Limitations

| Marker | Cancer Types | Functional Role | Limitations/Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| CD44 | Breast, pancreatic, HNSCC | Hyaluronan receptor, adhesion, signaling | Also expressed on normal stem cells and immune cells [5] |

| CD133 | Glioblastoma, colon cancer | Transmembrane glycoprotein, function not fully understood | Expression varies with tumor stage and hypoxia [5] |

| ALDH1 | Breast, colon, OSCC | Detoxifying enzyme, retinoic acid metabolism | Isoform-specific functions, technical variability in detection [8] |

| EpCAM | Prostate, GI cancers | Cell adhesion, signaling | Widespread epithelial expression limits targeting specificity [5] |

| p75NTR | OSCC, melanoma, esophageal | Nerve growth factor receptor | Heterogeneous expression within tumors [8] |

| LGR5 | Gastric cancer | Wnt pathway regulator, stem cell marker | Limited to specific cancer types and locations [12] |

Methodological Approaches for CSC Identification and Validation

Robust experimental frameworks are essential for accurate CSC characterization, combining surface marker analysis with functional validation.

Core Methodologies for CSC Isolation and Characterization

- Surface marker-based isolation: Flow cytometry enables precise enrichment of CSC subpopulations using specific marker combinations such as CD44+CD24-/low in breast cancer or CD34+CD38- in AML [5] [11].

- Aldefluor assay: Detects elevated aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) activity, allowing fluorescence-based separation of ALDH-high cells with stem-like properties [11].

- Sphere formation assays: When cultured in serum-free, non-adherent conditions, CSCs generate three-dimensional spheres, reflecting self-renewal capacity and stemness maintenance over multiple passages [11].

- In vivo tumorigenicity assays: The gold standard for CSC validation, wherein sorted cells are injected into immunocompromised mice to evaluate tumor-initiating potential, with minimal cell populations often sufficient to generate tumors [11].

These methodologies establish a framework for identifying and characterizing CSCs, bridging molecular observations with clinically relevant phenotypes. Integration of these approaches provides complementary evidence for CSC properties and functions [11].

Advanced Technologies in CSC Research

Emerging technologies are refining our ability to characterize CSCs and their dynamic behavior:

- Single-cell sequencing: Enables characterization of CSC heterogeneity and stem-like features at unprecedented resolution [5].

- CRISPR-based functional screens: Identify genes essential for CSC maintenance and survival [5].

- Patient-derived organoids (PDOs): Bridge the gap between in vitro cell lines and in vivo models, preserving tumor heterogeneity and enabling precision medicine approaches [11].

- AI-driven multiomics analysis: Integrates complex datasets to identify CSC vulnerabilities and predictive biomarkers [5].

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for CSC Identification. This diagram outlines the key methodological approaches for isolating and validating cancer stem cells.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for CSC Studies

| Reagent/Material | Primary Function | Application Examples | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorescently-labeled antibodies (CD44, CD133, EpCAM) | Surface marker detection and FACS isolation | Immunophenotyping, CSC enrichment | Validation for specific applications essential [11] |

| Aldefluor assay kit | Detection of ALDH enzyme activity | Functional identification of CSCs | Requires specific inhibition controls [11] |

| Serum-free sphere culture media | Support CSC growth in non-adherent conditions | Sphere formation assays, CSC expansion | Formulations often require growth factor supplementation [11] |

| Matrigel/ECM components | 3D culture substrate | Organoid generation, invasion assays | Batch variability requires standardization [11] |

| Immunodeficient mice (NSG, NOG) | In vivo tumorigenicity studies | Limiting dilution assays, therapeutic testing | Strain-specific engraftment characteristics [11] |

| Single-cell RNA sequencing kits | Transcriptomic profiling | Heterogeneity analysis, subpopulation identification | Requires fresh viable cells, computational expertise [5] |

Understanding the dual origins of CSCs from both tissue-resident stem cells and dedifferentiated cells has profound implications for cancer therapy development. The dynamic plasticity of CSCs and their ability to transition between stem-like and differentiated states represents a significant challenge for targeted therapies [2]. Furthermore, the presence of multiple CSC subpopulations with distinct phenotypes within individual tumors suggests that effective therapeutic approaches will need to address this heterogeneity [8]. Emerging strategies such as dual metabolic inhibition, immune-based approaches using CAR-T cells targeting CSC markers like EpCAM, and niche-targeting agents show promise in overcoming CSC-mediated therapy resistance [5] [2]. However, major challenges remain in targeting CSCs without affecting normal stem cells and in developing reliable biomarkers for patient stratification [5]. Moving forward, integrative approaches combining metabolic reprogramming, immunomodulation, and targeted inhibition of CSC vulnerabilities will be essential for developing effective CSC-directed therapies that address both the origins and adaptive capabilities of these critical tumor-propagating cells.

Core stemness transcription factors—OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, and SALL4—constitute a critical regulatory network that maintains pluripotency in embryonic stem cells. In oncogenesis, these factors are re-expressed and drive cancer stem cell (CSC) pathogenesis, contributing to tumor initiation, therapeutic resistance, and metastatic dissemination. This whitepaper delineates the molecular functions, interrelationships, and clinical relevance of these factors, framing them within the significant challenge of CSC identification and targeting. Supported by contemporary research, we provide methodologies for their investigation and discuss their emerging role as biomarkers and therapeutic targets in precision oncology.

Cancer stem cells (CSCs) are a minor subpopulation within tumors endowed with self-renewal, differentiation capacity, and enhanced resistance to conventional therapies, thereby driving tumor relapse and metastatic spread [5] [13]. The CSC hypothesis posits that a hierarchical organization exists within tumors, with CSCs at its apex, and their identification remains a central challenge in oncology [14]. A major obstacle is the lack of universal CSC markers, as surface proteins like CD44 and CD133 are not exclusive to CSCs and vary significantly across tumor types [5].

Attention has therefore shifted to intrinsic molecular regulators of stemness, particularly the core transcription factors OCT4 (Octamer-binding transcription factor 4), SOX2 (SRY-box transcription factor 2), NANOG (Nanog homebox), and SALL4 (Spalt-like transcription factor 4). These factors are paramount for maintaining pluripotency and self-renewal in embryonic stem cells (ESCs) [15] [16]. After development, their expression is largely silenced in adult tissues but is aberrantly re-activated in numerous cancers [14] [16]. They form a complex interconnected regulatory network that promotes the CSC phenotype, and their expression is frequently correlated with aggressive disease, resistance to treatment, and poor prognosis [17] [15]. Thus, understanding these factors is crucial for advancing CSC research and developing novel therapeutic strategies.

Molecular Functions and Interrelationships

The core transcription factors do not operate in isolation but form a tightly knit, self-reinforcing network that maintains pluripotency and stemness.

The Core Pluripotency Network (OCT4, SOX2, NANOG)

OCT4, SOX2, and NANOG form a critical core circuit that auto-regulates and co-occupies target gene promoters to sustain the pluripotent state [15] [18]. OCT4 is a POU-family transcription factor essential for maintaining the self-renewal of ESCs; its precise expression level is critical, as deviation can lead to differentiation [16]. SOX2, an HMG-box transcription factor, frequently co-operates with OCT4, forming heterodimers on composite DNA elements to regulate a common set of target genes, including their own promoters [18]. NANOG, a homeodomain protein, functions as a key determinant of pluripotency by blocking differentiation pathways [15]. This core circuit is reinforced by direct protein-protein interactions between the factors. For instance, research has demonstrated that OCT4, SOX2, and NANOG each individually form complexes with nucleophosmin (Npm1), a protein highly expressed in ESCs, suggesting a mechanism for their coordinated activity in maintaining the stem cell phenotype [18].

SALL4 as an Integrative Regulator

SALL4 is a zinc-finger transcription factor that serves as a vital integrator within the pluripotency network. Similar to the core factors, SALL4 is highly expressed in ESCs and is mostly silenced in adult tissues, with expression restricted to germ cells [16]. It participates in an interconnected autoregulatory loop with OCT4, SOX2, and NANOG, where each factor can regulate its own expression and that of the others [16]. SALL4 is known to antagonize OCT4's activation function to balance its expression level, fine-tuning the network [16]. Furthermore, SALL4 is a downstream target of the canonical WNT signaling pathway, positioning it as a nexus that integrates external signals with the core transcriptional machinery [16]. Its function is critical, as SALL4-null embryos do not survive beyond embryonic day E6.5 [16].

Table 1: Core Stemness Transcription Factors: Functions and Interactions

| Transcription Factor | Key Structural Features | Primary Molecular Function | Key Interaction Partners |

|---|---|---|---|

| OCT4 | POU DNA-binding domain | Maintains self-renewal; prevents differentiation [18] | SOX2, NANOG, Npm1, SALL4 [16] [18] |

| SOX2 | HMG-box domain | Cooperates with OCT4; regulates shared target genes [18] | OCT4, NANOG, Npm1, SALL4 [16] [18] |

| NANOG | Homeodomain | Blocks differentiation; sustains pluripotency [15] | OCT4, SOX2, Npm1, SALL4 [16] [18] |

| SALL4 | Multiple zinc-finger clusters | Integrates signals (e.g., WNT); fine-tunes core network [16] | OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, epigenetic modifiers [16] |

Experimental Analysis and Methodologies

Investigating the expression and function of core stemness factors requires a multifaceted approach. Below is a detailed protocol for assessing protein-protein interactions, a key methodology for understanding the functional network.

Protocol: Detecting Protein-Protein Interactions viaIn SituProximity Ligation Assay (PLA)

The in situ PLA technique allows for the visualization of direct protein-protein interactions within the cellular context with high specificity and sensitivity [18].

1. Sample Preparation and Staining:

- Cell Culture: Grow embryonic stem cells (ESCs) or CSCs on sterile glass coverslips in appropriate medium.

- Fixation and Permeabilization: Fix cells with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes at room temperature. Permeabilize cells with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 minutes.

- Blocking: Incubate cells with a blocking solution (e.g., 10% goat serum in PBS) for 1 hour at room temperature to prevent non-specific antibody binding.

2. Primary Antibody Incubation:

- Incubate the fixed and permeabilized cells with pairs of primary antibodies raised in different host species targeting the proteins of interest (e.g., rabbit anti-OCT4 and mouse anti-Npm1) [18].

- Dilute antibodies in blocking buffer according to their optimal concentrations (e.g., 1:1600 for OCT4 [17]) and incubate overnight at 4°C.

3. PLA Probe Incubation and Ligation:

- After washing, incubate the samples with secondary antibodies (PLA probes) conjugated to unique DNA oligonucleotides. These are typically anti-mouse MINUS and anti-rabbit PLUS probes.

- Perform a ligation reaction by adding a connector oligonucleotide that hybridizes to the two PLA probes. Only if the two target proteins are in close proximity (<40 nm) will the circle be completed by a DNA ligase.

4. Amplification and Detection:

- Amplify the ligated DNA circle through rolling-circle amplification using a fluorescently labelled nucleotide (e.g., Alexa Fluor 594).

- Counterstain the cell nuclei with Hoechst 33342 or DAPI.

- Mount the coverslips and visualize the red fluorescent signals (each representing a single protein-protein interaction event) using confocal microscopy [18].

Troubleshooting Notes:

- High Background: Optimize antibody concentrations and increase the stringency of washes. Include a no-primary-antibody control.

- No Signal: Validate antibody compatibility for immunostaining and PLA. Ensure all enzymatic reaction steps are performed correctly.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents for Investigating Core Stemness Factors

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Validated Antibodies | Rabbit anti-OCT4 (C52G3, CST) [17]; Mouse anti-SOX2 (L1D6A2, CST) [17]; Mouse anti-NANOG (1E6C4, CST) [17] | Immunofluorescent staining, Western blot, co-immunoprecipitation for protein detection and interaction studies. |

| Cell Culture Models | Embryonic Stem Cells (ESCs); Induced Pluripotent Stem (iPS) cells; Patient-derived CSC organoids [5] | In vitro models for studying stemness mechanisms, differentiation, and drug screening. |

| Gene Manipulation Tools | CRISPR-Cas9; shRNA vectors for knockdown [5] [16] | Functional studies to determine the role of specific factors in self-renewal and pluripotency. |

| Detection Kits | In Situ PLA Kits (e.g., Duolink) [18] | Sensitive detection of protein-protein interactions in situ. |

| Differentiation Inducers | Retinoic Acid; Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO); LIF Withdrawal [18] | Tools to induce differentiation and study the downregulation of stemness factors. |

Clinical and Prognostic Significance in Cancer

The expression of OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, and SALL4 in cancers is not merely incidental but is strongly correlated with aggressive clinicopathological features and poor patient outcomes, underscoring their prognostic utility.

A pivotal 2017 study on rectal cancer (RC) patients provides compelling quantitative evidence. The study demonstrated that tumor tissue expressions of OCT4, SOX2, and NANOG were significantly higher than in adjacent normal tissues (p<0.001 for OCT4 and NANOG, p=0.003 for SOX2) [17]. Critically, OCT4 expression was positively correlated with pathological grade (R=0.185, p=0.022), tumor size (R=0.224, p=0.005), and lymph node metastasis (N stage, R=0.170, p=0.036). NANOG expression was also positively associated with larger tumor size (R=0.169, p=0.036) [17]. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis revealed that OCT4 positivity was associated with significantly worse overall survival (OS) compared to OCT4-negative patients (p<0.001). Furthermore, the study established that having at least two positive markers was associated with shorter OS, and patients with all three markers positive had the worst prognosis [17]. Multivariate Cox analysis confirmed OCT4 as an independent prognostic factor for shorter OS (p<0.001) [17].

This prognostic significance extends beyond gastrointestinal cancers. A 2025 systematic review of salivary gland malignancies confirmed that the immunohistochemical expression of SOX2, OCT4, and NANOG is linked to tumor aggressiveness and poor prognosis, suggesting their combined assessment could serve as a powerful tool for risk stratification [15]. SALL4, as an oncofetal protein, is also re-expressed in various aggressive cancers, including hepatocellular carcinoma and leukemias, and its presence is often a marker of poor differentiation and treatment resistance [16].

Table 3: Prognostic Correlations of Core Stemness Factors in Human Cancers

| Transcription Factor | Cancer Type(s) Studied | Correlation with Clinicopathological Features | Impact on Survival |

|---|---|---|---|

| OCT4 | Rectal Cancer [17] | Poor differentiation, Larger tumor size, Higher N stage [17] | Independent predictor of shorter overall survival [17] |

| SOX2 | Rectal Cancer, Salivary Gland Malignancies [17] [15] | Overexpression in tumor vs. normal tissue [17] [15] | Not an independent factor in RC; associated with aggressiveness in SGM [17] [15] |

| NANOG | Rectal Cancer, Salivary Gland Malignancies [17] [15] | Larger tumor size (RC) [17] | Not an independent factor in RC; prognostic in SGM [17] [15] |

| SALL4 | Hepatocellular Carcinoma, Leukemias [16] | Poor differentiation, Therapy resistance [16] | Marker of aggressive disease and poor outcome [16] |

Therapeutic Targeting and Future Perspectives

Targeting the core stemness pathway network represents a frontier in overcoming therapy resistance and preventing cancer relapse. The inherent challenges include the plasticity of CSCs, the lack of unique surface markers, and the risk of on-target toxicity against normal stem cells [5] [13]. Several promising strategies are under investigation.

1. Direct Transcriptional Targeting: A major focus is developing inhibitors that disrupt the function of these transcription factors or their upstream regulators. This includes targeting the key signaling pathways (Wnt/β-catenin, Notch, and Hedgehog) that sustain the expression and activity of the core network [13] [19]. For instance, molecular targeting of OCT4 and its associated pathways is being explored to sensitize CSCs to conventional therapies [20].

2. Immunological Approaches: Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR) T-cell therapies and cancer vaccines are being designed to target CSC-specific antigens. While identifying unique targets is difficult, the shared expression of these factors with ESCs offers a potential avenue, albeit with safety challenges. Preclinical studies targeting EpCAM, a marker associated with CSCs, have shown promise [5]. The development of "Boolean logic" CAR T-cells that require recognition of two CSC-associated markers to activate is a promising strategy to enhance specificity and spare normal tissues [21].

3. Combination Therapies: Given the resilience and adaptability of CSCs, the most viable strategy may be combining conventional cytoreductive therapies (chemotherapy, radiation) with novel agents that specifically target the CSC population. This approach aims to eradicate the bulk tumor while disabling the engine of recurrence and metastasis [19]. Experts forecast that advances in 2025 will include the clinical evaluation of such combinatorial approaches, alongside improved biomarkers for patient selection [21].

The following diagram illustrates the interconnected regulatory relationships and external pathways influencing the core stemness factors, highlighting potential therapeutic intervention points.

Diagram Title: Core Stemness Factor Network and Therapeutic Targeting

The core stemness transcription factors OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, and SALL4 are central orchestrators of the pluripotent state in ESCs and are critically re-activated in CSCs. They form a robust, self-reinforcing network that promotes self-renewal, inhibits differentiation, and confers formidable resistance to conventional cancer therapies. Their expression provides valuable prognostic information and represents a promising, though challenging, avenue for therapeutic intervention. Future research, leveraging single-cell multi-omics, advanced organoid models, and AI-driven analysis, will be essential to decode the context-specific functions of these factors and translate this knowledge into effective CSC-targeted therapies that can ultimately improve long-term patient survival [5] [21].

Cancer stem cells (CSCs) constitute a highly plastic and therapy-resistant cell subpopulation within tumors that drives tumor initiation, progression, metastasis, and relapse [5]. Their ability to evade conventional treatments, adapt to metabolic stress, and interact with the tumor microenvironment makes them critical targets for innovative therapeutic strategies. The reliable identification and isolation of CSCs represent a fundamental challenge in cancer research, as the absence of universal CSC markers and significant heterogeneity across tumor types complicates their study [5] [13]. Among the numerous biomarkers investigated, four surface markers—CD44, CD133, ALDH1, and ICAM1—have emerged as particularly significant across multiple cancer types. These markers facilitate not only the identification of CSCs but also participate in critical functional mechanisms including maintenance of stemness, immune evasion, and therapeutic resistance. This technical guide provides an in-depth analysis of these four key markers, detailing their biological functions, expression patterns, methodological approaches for detection, and their interrelationships within the CSC signaling network, framed within the context of ongoing challenges in CSC marker research.

Marker Profiles and Functional Significance

CD44: A Multifunctional CSC Marker with Immunological Significance

CD44, a transmembrane glycoprotein receptor for hyaluronic acid, is one of the most extensively studied cancer stem cell markers across numerous malignancies. It plays a crucial role in cell-to-cell and cell-to-matrix adhesion, while also participating in angiogenesis, invasion, and migration in oral and oropharyngeal cancer [22]. CD44 exists as a standard isoform (CD44s) or alternatively spliced variant isoforms (CD44v), with these variants frequently undergoing alternative splicing to support cancer progression and are associated with poor survival [23].

Recent pan-cancer analyses have revealed that elevated CD44 expression correlates with tumor stage and prognosis in several different cancers [23]. Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) results demonstrate that upregulated CD44 involves cancer stem cell-associated processes, antigen processing and presentation, and immune cell proliferation and activation [23]. CD44 plays an essential role in tumor immune regulation and immune checkpoint inhibitor response, with its expression positively correlated with regulatory CD4 T cells, macrophages M1 and M2 in several analyzed cancers [23]. In terms of diagnostic utility, studies in oral and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (OOSCC) have demonstrated distinctive expression patterns across differentiation states, with strong CD44 immunopositivity observed in 29 out of 31 well-differentiated OOSCC cases, while none of the poorly differentiated OOSCC cases showed strong staining intensity [22]. This pattern of decreasing CD44 expression from well-differentiated to poorly differentiated OSCC highlights its context-dependent expression and potential role in maintaining differentiated phenotypes in certain cancer types [22].

Table 1: CD44 Expression Patterns and Clinical Correlations Across Cancers

| Cancer Type | Expression Pattern | Clinical Correlation | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oral & Oropharyngeal SCC | Strong in well-differentiated (29/31 cases); decreases with dedifferentiation | Statistically significant correlation with histological grade (p < 0.05) [22] | IHC staining intensity graded strong, moderate, or weak |

| Pan-Cancer Analysis | Upregulated in multiple cancer types | Correlates with tumor stage, prognosis, and immune infiltration [23] | Bioinformatics analysis of TCGA data |

| Triple-Negative Breast Cancer & NSCLC | Positively regulates PD-L1 expression | Potential role in immune checkpoint regulation [23] | Binds to regulatory region of PD-L1 locus |

CD133 (PROM1): A Conserved Stem Cell Glycoprotein

CD133 (prominin-1), a pentaspan transmembrane glycoprotein, is widely expressed in the stem cell population of various tumor types and represents one of the most extensively studied CSC markers [24]. In colorectal cancer (CRC), CD133 serves as a reliable marker for identifying cancer stem-like cells, with CD133+ cells demonstrating higher proliferation, colony-forming ability, drug resistance, and tumorigenicity compared to CD133- cells [25]. These functional characteristics confirm the stem-like properties of CD133+ populations and their critical role in tumor maintenance and progression.

In early-stage non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), CD133 is significantly upregulated in tumor tissues compared with adjacent normal tissues and healthy controls [24]. Its high expression correlates with poor differentiation, larger tumor size (≥3 cm), lymph node metastasis, and advanced stage (IB-IIA) [24]. The diagnostic performance of CD133 in NSCLC is robust, with ROC analysis showing an AUC of 0.809, demonstrating its value as a diagnostic biomarker [24]. When combined with OCT4, another stemness marker, the diagnostic accuracy improves substantially (AUC=0.893), with combined sensitivity of 88.7% and specificity of 82.5% [24]. From a prognostic perspective, patients with high CD133 expression exhibit markedly reduced 2-year overall survival compared with low-expression cases, and multivariate Cox regression identifies high CD133 expression as an independent prognostic risk factor (HR=2.45, 95% CI: 1.38-4.36, P=0.003) [24].

Table 2: CD133 Diagnostic and Prognostic Performance Across Studies

| Study Context | Diagnostic Performance | Prognostic Value | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early-stage NSCLC (80 patients) | AUC: 0.809; Combined with OCT4: AUC=0.893 [24] | HR=2.45, 95% CI: 1.38-4.36, P=0.003 [24] | Independent prognostic factor; associated with aggressive disease |

| Colorectal Cancer (multiple cell lines) | Reliable identification of CRC stem-like cells [25] | Associated with metastasis and relapse [25] | CD133+ cells show higher proliferation, drug resistance, and tumorigenicity |

ALDH1: Metabolic Marker of Stemness

Aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 (ALDH1) represents a functional CSC marker based on enzymatic activity rather than surface expression alone. ALDH1 is a detoxifying enzyme responsible for the oxidation of intracellular aldehydes and exists in different isoforms, with the ALDEFLUOR assay system specifically developed to detect ALDH1 isoform activity [26]. This enzymatic activity-based identification approach provides a complementary method to surface marker detection for isolating putative CSCs.

The ALDEFLUOR assay was originally developed for identifying ALDH-expressing hematopoietic stem cells but has since been adapted for solid tumors [26]. The assay detects cells with high ALDH enzyme activity, which characterizes stem and progenitor cells across various tissues. In breast cancer research, ALDH-positive cells isolated from human breast tumors contain CSCs capable of generating tumors in NOD/SCID mice, while ALDH-negative cells lack this tumor-initiating capacity [26]. Similar findings have been reported in CSCs from the colon, brain, and liver [26]. The expression of ALDH varies between different types of cell lines, with SKBR3 cells serving as a positive control due to high ALDH expression, while MCF7 cells express little to no ALDH and can function as a negative control [26]. Optimal staining conditions for the ALDEFLUOR assay require incubation between 30-45 minutes in a 37°C water bath, as extended incubation (60 minutes) diminishes ALDH staining intensity [26].

Recent advancements in ALDH detection include the development of novel fluorescent probes such as AldeCou1-4, designed using a coumarin-linker-benzaldehyde scaffold [27]. Among these, AldeCou-1 exhibits a significant Stokes shift of 125 nm (λex/λem = 380/505 nm), which enhances the signal-to-noise ratio and minimizes inner-filter effects [27]. Compared to conventional ALDH activity assay kits like ALDEFLUOR, which require additional buffers and inhibitors that complicate imaging protocols, AldeCou-1 enables simplified assay conditions by eliminating the need for ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter inhibitors and specialized buffers [27].

ICAM1: Emerging Regulator of CSC Stemness and Immune Evasion

Intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM1) has recently emerged as a key regulator of CSC stemness and tumorigenicity, particularly in glioblastoma (GBM), where it promotes an immunosuppressive microenvironment via β-catenin/PD-L1 signaling [28]. ICAM1 is a cell surface glycoprotein typically expressed on endothelial cells and specific leukocytes, historically known for facilitating endothelial-leukocyte transmigration through its interaction with lymphocyte function-associated antigen 1 (LFA-1) and macrophage antigen 1 (MAC-1) [28].

In GBM, ICAM1 overexpression is associated with adverse patient outcomes, with elevated levels observed in various patient-derived GBM stem cells (GSCs) [28]. Mechanistically, ICAM1 interacts with ZNRF3, leading to its autoubiquitination and clearance, which stabilizes LRP6 and activates β-catenin signaling, subsequently upregulating PD-L1 expression [28]. This ICAM1/β-catenin/PD-L1 signaling axis establishes a critical link between stemness maintenance and immune evasion in GBM. ICAM1's role extends to the recurrent GBM setting, where hypoxic conditions induce endothelial cells to upregulate ICAM1 expression, facilitating the recruitment of bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) [29]. Concurrently, endothelial-derived CCL2 induces the expression of adrenomedullin (ADM) in BMDMs, and this macrophage-derived ADM subsequently accelerates angiogenesis in endothelial cells while enhancing the proliferation and migration of tumor cells [29]. This feedforward loop in the endothelial-BMDM-tumor cell axis provides mechanistic insights into the tumor microenvironment of recurrent GBM.

Therapeutic targeting of ICAM1 in combination with immune checkpoint blockade shows promising results. Combined treatment with anti-ICAM1 and anti-PD-1 antibodies results in the most effective tumor inhibition and significantly extends survival in ICAM1-overexpressing GBM models [28]. CyTOF and flow cytometry analyses reveal that ICAM1 overexpression reduces cytotoxic CD8+ T cell populations via PD-L1/PD-1 interactions, an effect reversible by PD-1 blockade [28].

Table 3: ICAM1 Expression and Functional Roles in GBM

| Aspect | Findings | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Expression Pattern | Elevated in recurrent GBM and specific GSC lines (528, 83, GSC209) [28] | scRNA-seq, flow cytometry, IHC |

| Stemness Regulation | Maintains self-renewal, proliferation, and tumorigenicity of GSCs [28] | Knockdown reduces sphere formation; overexpression enhances it |

| Immune Modulation | Reduces CD8+ T cell populations via PD-L1/PD-1 [28] | CyTOF, flow cytometry, reversible by PD-1 blockade |

| Therapeutic Targeting | Combined anti-ICAM1 + anti-PD-1 most effective [28] | Mouse GBM models showing survival extension |

Methodological Approaches for CSC Marker Analysis

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) Protocols

Immunohistochemistry represents a fundamental methodology for detecting CSC markers in tissue sections, providing spatial context that is crucial for understanding tumor heterogeneity. A standardized IHC protocol for CD44 and similar markers involves several critical steps [22] [24]:

Tissue Section Processing: Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections are cut at 4μm thickness, mounted on glass slides, and baked at 60°C for 2 hours. Deparaffinization is performed with xylene (2×10 minutes), followed by gradient rehydration using 100%, 95%, 85%, and 75% ethanol (5 minutes each). After rinsing with tap water, antigen retrieval is performed using 0.01 mol/L citrate buffer (pH 6.0) heated in a microwave at medium-high power for 10 minutes, then naturally cooled to room temperature. Endogenous peroxidase activity is blocked by incubating with 3% hydrogen peroxide for 10 minutes at room temperature, followed by PBS washing (3×) [24].

Antibody Incubation and Staining: Slides are incubated with normal goat serum blocking solution for 20 minutes at room temperature to block non-specific binding. Primary antibodies are then applied: for CD133 (Abcam, Cat# ab19898, dilution 1:200) and OCT4 (Abcam, Cat# ab19857, dilution 1:150) as an example [24]. Slides are incubated in a humid chamber at 4°C overnight, followed by PBS washes and application of HRP-conjugated secondary antibody incubated at room temperature for 30 minutes. DAB is used for color development (3-8 minutes), monitored under a microscope for optimal effect. Hematoxylin counterstaining is performed for 30 seconds, followed by dehydration, clearing, and mounting [24].

Interpretation of Staining Results: Evaluation should be performed by two experienced pathologists independently in a double-blinded manner. A semi-quantitative scoring method is recommended, with total score = staining intensity × percentage of positive cells. Staining intensity is scored as: no color (0), light yellow (1), brown-yellow (2), or brown (3). Positive cell percentage is scored as: <5% (0), 5-25% (1), 26-50% (2), 51-75% (3), or >75% (4). The total score ranges from 0 to 12, with scores ≥6 typically defined as "high expression" and <6 as "low expression" [24].

Flow Cytometry and Cell Sorting

Flow cytometry enables quantitative analysis and sorting of live CSC populations based on surface marker expression. The following protocols detail specific approaches for different markers:

ALDEFLUOR Assay for ALDH1 Activity Detection: The ALDEFLUOR assay requires pre-warming cell culture medium, Trypsin-EDTA, D-PBS and all ALDEFLUOR Kit reagents to room temperature [26]. Cells are trypsinized to create a single-cell suspension and centrifuged at 300 × g for 7 minutes. After supernatant removal, the cell pellet is resuspended in 1 mL of room temperature ALDEFLUOR assay buffer. Viable cell concentration is determined by Trypan Blue exclusion and adjusted to 1×10^5–1×10^6 cells/mL. The cell suspension is divided into "test" and "control" tubes, with 5 μL of 1.5 mM DEAB solution added to the control tube. Then, 5 μL of activated ALDEFLUOR substrate per mL of sample is added to the test tube, immediately followed by transfer of 0.5 mL to the DEAB control tube (final DEAB concentration 15μM). Samples are incubated for 30-45 minutes in a 37°C water bath (not exceeding 60 minutes). Following incubation, tubes are centrifuged at 4°C for 5 minutes at 300 × g, supernatant aspirated, and cell pellet resuspended in 0.5 mL of ice-cold ALDEFLUOR assay buffer. Samples are kept on ice and analyzed by flow cytometry shortly after staining [26].

CD133 Cell Sorting Using Magnetic-Activated Cell Sorting (MACS): For identification of colorectal cancer stem-like cells, CD133+ cells can be isolated from human (LoVo, HCT116, and SW620) and mouse (CT26) CRC cell lines using magnetic-activated cell sorting and flow cytometry [25]. The isolated CD133+ cells demonstrate higher proliferation, colony-forming ability, drug resistance, and tumorigenicity compared to CD133- cells, validating their stem-like characteristics [25].

Molecular Analysis Techniques

Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR): For gene expression analysis of CSC markers, qRT-PCR provides sensitive quantification. RNA is extracted from tissues or sorted cells, reverse transcribed to cDNA, and amplified using marker-specific primers. In CD133/OCT4 studies in NSCLC, expression levels are assessed relative to control genes and compared between tumor tissues and adjacent normal tissues [24].

Single-Cell RNA Sequencing (scRNA-seq): Advanced scRNA-seq protocols enable comprehensive analysis of CSC heterogeneity. For ICAM1 studies in GBM, researchers process single-cell RNA data using Seurat v5.1.0, applying quality control steps to remove cells with nFeature <500 or >7,000, mitochondrial gene expression >10%, erythrocyte gene expression >3%, or nCount <1,000 [29]. Principal component analysis and Harmony integration are performed after data normalization and feature selection, with t-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding for visualization. Marker genes are identified using FindAllMarkers, and malignant/non-malignant cells are distinguished using inferCNV [29].

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Mechanisms

The four CSC markers function within interconnected signaling networks that regulate stemness maintenance, survival, and immune evasion. Understanding these pathways is essential for developing effective CSC-targeted therapies.

Diagram 1: CSC Marker Signaling Network. This diagram illustrates the molecular interactions between key CSC markers and their downstream signaling pathways that regulate stemness, immune evasion, and therapy resistance.

Integrated CSC Marker Signaling

The signaling network illustrates how these four CSC markers coordinate to maintain the stem cell state. ICAM1 activates β-catenin signaling through ZNRF3 interaction and LRP6 stabilization, leading to PD-L1 upregulation [28]. This mechanism directly links adhesion molecule signaling with immune checkpoint regulation. CD44 contributes to stemness maintenance through multiple mechanisms, including direct regulation of PD-L1 expression in triple-negative breast cancer and NSCLC by binding to the regulatory region of the PD-L1 locus [23]. CD133 functions as a core component of stemness maintenance machinery, though its specific signaling partners vary by cancer type. ALDH1 provides metabolic support for stemness through detoxification of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and other aldehydes, creating a permissive environment for CSC maintenance [26] [27]. Together, these markers create a robust network that sustains the CSC phenotype while enabling immune evasion and therapy resistance.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for CSC Marker Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antibodies for IHC | Anti-CD133 (Abcam ab19898), Anti-OCT4 (Abcam ab19857) | Marker detection in tissue sections | Dilutions 1:150-1:200; citrate buffer antigen retrieval [24] |

| Flow Cytometry Assays | ALDEFLUOR Kit (StemCell Technologies #01700) | Detection of ALDH enzyme activity | Incubate 30-45 min at 37°C; DEAB control essential [26] |

| Cell Separation | Magnetic-activated cell sorting (MACS) for CD133 | Isolation of live CSC populations | Enables functional studies of sorted populations [25] |

| Novel Probes | AldeCou1-4 fluorescent probes | ALDH detection with improved S/N ratio | 125 nm Stokes shift; simplified protocol vs. ALDEFLUOR [27] |

| Cell Culture Models | Patient-derived GSCs (e.g., 528, 83, GSC209) | Functional studies of CSC populations | Maintain stemness in defined conditions [28] |

Experimental Workflows for CSC Identification

Diagram 2: Comprehensive CSC Identification Workflow. This workflow outlines the key methodological steps from sample collection through data integration for rigorous identification and validation of cancer stem cells using multiple complementary approaches.

Challenges and Future Perspectives in CSC Marker Research

Despite significant advances in CSC marker identification, several challenges persist in the field. The absence of universally reliable CSC biomarkers across cancer types remains a major obstacle, compounded by significant heterogeneity even within specific cancer types [5]. Marker expression varies considerably across tumor types, reflecting the influence of tissue origin and microenvironmental context on CSC phenotypes [5]. Furthermore, stem-like features can be acquired de novo by non-CSCs in response to environmental stimuli such as hypoxia, inflammation, or therapeutic pressure, indicating that CSCs may represent a dynamic functional state rather than a static subpopulation [5].

The clinical translation of CSC marker knowledge faces additional hurdles. While CD44, CD133, ALDH1, and ICAM1 show promise as therapeutic targets, their expression in normal stem cells raises concerns about on-target, off-tumor effects [5] [13]. The dynamic plasticity of CSCs further complicates therapeutic targeting, as elimination of one CSC subpopulation may enable the emergence of alternative subpopulations utilizing different markers and signaling pathways [13].

Future perspectives in CSC marker research include the development of multi-marker panels that better capture CSC heterogeneity, the integration of single-cell technologies for refined subpopulation characterization, and the creation of novel therapeutic approaches that simultaneously target multiple CSC features. Emerging strategies such as dual metabolic inhibition, synthetic biology-based interventions, and immune-based approaches hold promise for overcoming CSC-mediated therapy resistance [5]. The combination of ICAM1 inhibition with PD-1 blockade demonstrates the potential of targeting both stemness and immune evasion pathways simultaneously [28]. Similarly, CD44's role in regulating PD-L1 expression suggests opportunities for combination strategies targeting both stemness and immune checkpoint mechanisms [23].

As technologies advance, the development of more sophisticated tools for CSC identification and targeting will continue to evolve. Novel approaches such as PET-leveraged ALDH probes [27], improved fluorescent probes with better signal-to-noise ratios, and advanced computational methods for analyzing CSC heterogeneity will enhance our ability to study and target these critical cell populations. Through continued refinement of marker identification techniques and elucidation of signaling networks, progress toward effective CSC-targeted therapies that address treatment resistance and recurrence may be achieved.

Cancer stem cells (CSCs) constitute a specialized subpopulation within tumors characterized by their capacity for self-renewal, differentiation into heterogeneous cancer cells, and enhanced resistance to conventional therapies. These cells are now recognized as central drivers of tumor initiation, progression, metastasis, and relapse [5]. The functional properties of CSCs—particularly their chemoresistance and immune evasion capabilities—are fundamentally regulated by a core set of evolutionarily conserved stemness signaling pathways [30]. These pathways, including Wnt/β-catenin, Notch, Hedgehog, and others, not only maintain stem-like properties but also enable CSCs to manipulate their microenvironment and evade immune destruction [31] [32].

The clinical significance of these pathways cannot be overstated. Their activity correlates strongly with poor patient outcomes across multiple cancer types, including digestive tract tumors, ovarian cancer, and breast cancer [33] [34]. Understanding the intricate workings of these signaling networks is therefore paramount for developing novel therapeutic strategies that can effectively target the CSC population and overcome the challenges of treatment resistance and disease recurrence [5] [30]. This technical review comprehensively examines the molecular mechanisms by which stemness signaling pathways coordinate self-renewal, chemoresistance, and immune evasion, providing a scientific framework for researchers and drug development professionals working to translate these insights into clinical applications.

Core Stemness Signaling Pathways: Molecular Mechanisms and Functional Outputs

Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling

The Wnt/β-catenin pathway serves as a master regulator of stem cell maintenance and fate decisions. In the canonical pathway, Wnt ligand binding to Frizzled receptors prevents the destruction complex from phosphorylating β-catenin, allowing β-catenin accumulation and nuclear translocation [34]. Once in the nucleus, β-catenin forms complexes with TCF/LEF transcription factors to activate target genes including c-MYC, CYCLIN D1, and CD44, which collectively promote self-renewal and cell cycle progression [5] [34]. Aberrant activation of this pathway is frequently observed in colorectal cancers and other gastrointestinal malignancies, where it drives CSC maintenance and tumor aggressiveness [34]. The pathway also contributes to chemoresistance through upregulation of drug efflux transporters and enhancement of DNA repair mechanisms [5].

Notch Signaling

Notch signaling operates via cell-to-cell communication, where transmembrane-bound ligands (Jagged and Delta-like) on one cell activate Notch receptors on adjacent cells, triggering proteolytic cleavage and release of the Notch intracellular domain (NICD) [30]. NICD translocates to the nucleus and forms a complex with CSL transcription factors, activating target genes such as HES and HEY that maintain the undifferentiated, self-renewing state of CSCs [33] [30]. In ovarian cancer, Notch signaling collaborates with the tumor microenvironment to enhance CSC survival following chemotherapy, and its inhibition has been shown to sensitize tumors to conventional treatments [33]. The pathway also supports immune evasion by modulating cytokine secretion and immune cell recruitment within the tumor niche [32].

Hedgehog Signaling

The Hedgehog (Hh) pathway is initiated by binding of Hedgehog ligands (SHH, IHH, DHH) to Patched receptors, which relieves suppression of Smoothened and enables activation of GLI transcription factors [35] [30]. GLI targets including SOX2, NANOG, and BMI-1 reinforce stemness and self-renewal capacity [30]. Hedgehog signaling exhibits extensive crosstalk with other stemness pathways and is particularly important in maintaining the CSC niche through stromal-epithelial interactions [33]. In digestive tract tumors, aberrant Hh signaling promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and metastatic progression, making it a compelling therapeutic target [34].

Additional Key Regulatory Pathways

Several other signaling cascades contribute significantly to CSC regulation. The PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway integrates growth factor signals to promote CSC survival, metabolic adaptation, and therapy resistance [5] [36]. TGF-β/SMAD signaling supports CSC maintenance and immune suppression through modulation of the tumor microenvironment [35] [33]. Hippo signaling, through its effectors YAP/TAZ, interfaces with mechanical cues from the extracellular matrix to influence CSC plasticity and expansion [5]. These pathways rarely operate in isolation; instead, they form an interconnected network that allows CSCs to adapt to therapeutic pressure and environmental challenges [35].

Table 1: Core Stemness Signaling Pathways in Cancer Stem Cells

| Pathway | Key Components | Primary Functions in CSCs | Therapeutic Inhibitors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wnt/β-catenin | Frizzled, β-catenin, TCF/LEF | Self-renewal, differentiation, EMT, chemoresistance | Porcupine inhibitors, Tankyrase inhibitors, β-catenin disruptors |

| Notch | DLL/Jagged, Notch receptors, NICD, CSL | Cell fate decisions, survival, chemoresistance, immune modulation | γ-Secretase inhibitors, monoclonal antibodies |

| Hedgehog | SHH/IHH, Patched, Smoothened, GLI | Self-renewal, niche maintenance, metastasis | Smoothened antagonists (vismodegib, sonidegib) |

| PI3K/AKT/mTOR | PI3K, AKT, mTOR, PTEN | Metabolism, survival, proliferation, therapy resistance | AKT inhibitors, mTOR inhibitors, dual PI3K/mTOR inhibitors |

| TGF-β | TGF-β ligands, SMADs | EMT, immune suppression, metastasis, stromal remodeling | TGF-β receptor kinase inhibitors, neutralizing antibodies |

| Hippo | MST1/2, LATS1/2, YAP/TAZ | Mechanical signaling, proliferation, organ size control, stemness | YAP/TAZ inhibitors, verteporfin |

Diagram 1: Core stemness signaling pathways converge on chemoresistance and immune evasion. Each pathway initiates with ligand-receptor interaction, transduces signals through cytoplasmic components, activates transcription factors, and ultimately regulates genes controlling CSC properties.

Mechanisms of Therapy Resistance Mediated by Stemness Pathways

Intrinsic Chemoresistance Mechanisms

CSCs exhibit multiple intrinsic resistance mechanisms that are directly regulated by stemness signaling pathways. The Wnt/β-catenin pathway enhances the expression of ATP-binding cassette (ABC) drug transporters, including ABCB1 and ABCG2, which efficiently efflux chemotherapeutic agents from CSCs [5]. Notch signaling promotes cell cycle quiescence, enabling CSCs to evade cell cycle-dependent chemotherapeutics [33]. Additionally, multiple stemness pathways enhance DNA repair capacity through upregulation of DNA damage response proteins and detoxifying enzymes such as ALDH1, which inactivates certain chemotherapeutic agents like cyclophosphamide [8] [30].

The PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway contributes significantly to therapy resistance by inhibiting apoptosis and promoting survival under stress conditions. AKT phosphorylation inactivates pro-apoptotic proteins while stabilizing anti-apoptotic factors, creating a robust protective mechanism against chemotherapy-induced cell death [36]. In ovarian cancer, the convergence of multiple stemness pathways creates a reinforced network of resistance mechanisms that allows CSCs to survive first-line chemotherapy and initiate disease recurrence [33].

Metabolic Adaptations

CSCs exhibit remarkable metabolic plasticity, enabled by stemness signaling pathways that facilitate adaptation to nutrient deprivation and therapeutic stress. The PI3K/AKT/mTOR axis coordinates a shift between glycolysis and oxidative phosphorylation depending on environmental conditions [5]. Hedgehog signaling promotes lipid metabolism rewiring, while Wnt activation enhances glutamine metabolism—adaptations that support CSC survival under chemotherapeutic stress [5] [30].

This metabolic reprogramming serves dual purposes: it maintains energy production and redox homeostasis in CSCs while simultaneously creating a metabolite-rich microenvironment that inhibits immune cell function. Lactate secretion from glycolytic CSCs acidifies the tumor microenvironment and suppresses cytotoxic T cell activity, while kynurenine production from tryptophan metabolism promotes regulatory T cell expansion [32]. These metabolic adaptations represent a crucial interface between chemoresistance and immune evasion mechanisms.

Table 2: Stemness Pathway-Mediated Resistance Mechanisms

| Resistance Mechanism | Key Pathway Regulators | Functional Consequences | Experimental Targeting Approaches |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drug efflux transporter upregulation | Wnt/β-catenin, Hedgehog | Reduced intracellular drug accumulation | ABC transporter inhibitors combined with pathway antagonists |

| Enhanced DNA repair capacity | Notch, PI3K/AKT | Reduced DNA damage from genotoxic agents | PARP inhibitors with Notch inhibitors |

| Metabolic plasticity | PI3K/AKT/mTOR, HIF-1α | Survival under nutrient and oxygen stress | Metabolic inhibitors (metformin, 2-DG) with pathway modulators |

| Epithelial-mesenchymal transition | TGF-β, Wnt, Notch | Enhanced invasive capacity, survival | Dual TGF-β/Wnt inhibition |

| Quiescence/G0 arrest | Notch, TGF-β | Evasion of cell cycle-active drugs | CDK4/6 inhibitors to force cell cycle entry |

| Autophagy activation | PI3K/AKT/mTOR, Hedgehog | Recycling of damaged organelles and proteins | Hydroxychloroquine with pathway inhibitors |

| Anti-apoptotic protein expression | PI3K/AKT, NF-κB | Resistance to apoptosis-inducing agents | BCL-2 inhibitors with AKT antagonists |

Immune Evasion Strategies Regulated by Stemness Pathways

Modulation of Immune Cell Infiltration and Function

Stemness signaling pathways enable CSCs to actively shape their immune microenvironment through the secretion of cytokines, chemokines, and exosomes that recruit and polarize immunosuppressive cells while excluding cytotoxic immune populations. CSCs secrete TGF-β, IL-10, CCL2, and CCL5, which recruit regulatory T cells (Tregs), myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), and tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) [32]. These immune cells create a protective niche around CSCs through multiple mechanisms: TAMs promote CSC stemness via IL-6 and TGF-β secretion; MDSCs inhibit T cell function through arginase-1 and reactive oxygen species production; and Tregs suppress antitumor immunity through CTLA-4 and IL-35-mediated mechanisms [32].

The Wnt/β-catenin pathway has been specifically linked to T cell exclusion from the tumor microenvironment, creating an "immune-privileged" site for CSCs [31]. This pathway activation leads to downregulation of chemokines that attract CD8+ T cells, effectively creating a physical barrier against immune attack. In digestive tract tumors, CSC-immune cell crosstalk establishes a self-reinforcing immunosuppressive loop that protects the CSC population from elimination [34] [32].

Immune Checkpoint Expression and Antigen Presentation Alterations

CSCs upregulate multiple immune checkpoint molecules as another mechanism of immune evasion. Notch and PI3K/AKT signaling induce PD-L1 expression on CSCs, enabling them to directly inhibit T cell activation through PD-1 engagement [32]. Additionally, CSCs exhibit reduced MHC class I expression, limiting their antigen presentation capacity and ability to be recognized by cytotoxic T cells [32]. Some CSC populations also upregulate non-classical MHC molecules such as HLA-G, which further suppresses immune responses [31].

The Hippo pathway effector YAP has been shown to promote PD-L1 expression in CSCs, while TGF-β signaling induces TIM-3 and LAG-3 checkpoint expression [5]. This multifaceted approach to immune checkpoint regulation allows CSCs to deploy numerous parallel mechanisms to resist immune-mediated killing, explaining why single-agent checkpoint blockade often fails to eliminate the CSC compartment.