Cross-Platform Validation of Multi-Gene Signature Assays: Strategies for Robust Clinical and Research Implementation

Multi-gene signature assays are transforming precision medicine by providing crucial prognostic and predictive insights in oncology and complex diseases.

Cross-Platform Validation of Multi-Gene Signature Assays: Strategies for Robust Clinical and Research Implementation

Abstract

Multi-gene signature assays are transforming precision medicine by providing crucial prognostic and predictive insights in oncology and complex diseases. However, their clinical utility is often limited by a lack of transferability across different measurement platforms, such as microarrays, RNA-sequencing, and targeted panels like NanoString. This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals, addressing the critical challenge of cross-platform validation. We explore the foundational need for platform-independent models, detail methodological innovations like ratio-based features and rank-based scoring, and present optimization frameworks for troubleshooting batch effects and data integration. Finally, we compare validation strategies and regulatory considerations, synthesizing key takeaways to guide the development of robust, clinically deployable genomic signatures that ensure reliable performance across technologies and institutions.

The Critical Need for Platform-Independent Biomarkers in Precision Medicine

The Problem of Technical Noise and Limited Reproducibility in Omics Signatures

The pursuit of precise and reliable biomarkers in genomics has been consistently challenged by the issues of technical noise and limited reproducibility. High-throughput omics technologies, while powerful, introduce significant technical variations that can obscure true biological signals and compromise the validity of molecular signatures. These challenges are particularly acute in the development of multigene signature assays, where consistency across different technology platforms and research centers is paramount for clinical translation. This guide objectively examines the core challenges and compares data on validation strategies that aim to mitigate these issues, providing a clear framework for evaluating assay performance in cross-platform contexts.

Technical noise and irreproducibility in omics signatures stem from multiple sources and have significant scientific consequences.

Sources of Technical Variance: Batch effects are notoriously common technical variations unrelated to study objectives. They can be introduced at virtually every stage of a high-throughput study, including sample preparation and storage (variations in protocol procedures, reagent lots, storage conditions), data generation (different laboratory conditions, personnel, sequencing machines, or analysis pipelines), and study design itself (non-randomized sample collection or confounded study designs) [1].

Profound Negative Impacts: When unaddressed, these technical variations can:

- Dilute genuine biological signals, reducing statistical power [1].

- Lead to misleading or biased conclusions, especially when batch effects correlate with biological outcomes of interest [1].

- Act as a paramount factor contributing to the reproducibility crisis in scientific research, potentially resulting in retracted articles and invalidated findings [1].

Case Study: Cross-Platform Validation of a LUAD Prognostic Signature

A 2025 multicenter study on Lung Adenocarcinoma (LUAD) exemplifies a systematic approach to developing a reproducible multigene signature. The research established a 14-gene glycolysis metabolism prognostic signature (14GM-PS) and rigorously validated it across different technology platforms [2].

Experimental Protocol and Validation Workflow

The study employed a comprehensive, multi-stage validation protocol:

- Data Collection: Gene expression and clinical data were collected from 1,238 curatively resected LUAD patients across 11 public datasets [2].

- Study Population: Patients had to meet strict inclusion criteria: histologically confirmed LUAD, stage I-IIIA TNM, available survival information, and treatment with curative resection only [2].

- Signature Discovery: A meta-discovery dataset (n=665) from three array-based datasets (GSE68465, GSE31210, GSE50081) was analyzed to extract prognostic genes from a functional perspective, specifically focusing on glycolysis-related genes [2].

- Cross-Platform Validation: The signature was validated in two independent validation datasets using different technologies:

- Validation I (n=299): Combined seven array-based datasets

- Validation II (n=274): Used RNA-Seq data from TCGA (Illumina HiSeq2000) [2]

- Bioinformatic Processing: For microarray datasets, the Robust Multi-array Average algorithm was used for preprocessing with log2-transformation and quantile normalization. For TCGA RNA-Seq data, normalized count values were log2-transformed. Analysis was restricted to 11,718 genes commonly measured across all platforms [2].

- Statistical Analysis: Prognostic performance was assessed using survival analyses (log-rank tests) and multivariate Cox regression, while a nomogram integrated the signature with clinicopathological factors [2].

Performance Results Across Platforms

Table 1: Performance Metrics of the 14GM-PS Signature Across Validation Cohorts

| Validation Cohort | Technology Platform | Sample Size | 5-Year Survival Discrimination | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Validation I | Multiple Affymetrix arrays | 299 | Significant difference | Log-rank P<0.001 |

| Validation II | Illumina HiSeq2000 RNA-Seq | 274 | Significant difference | Log-rank P=0.004 |

The 14GM-PS demonstrated consistent performance across different technology platforms (multiple Affymetrix arrays and Illumina RNA-Seq), with both validation cohorts showing statistically significant differences in 5-year survival rates [2]. Multivariate Cox analysis confirmed the signature as an independent prognostic factor, and the integration into a nomogram with clinical factors further improved prognostic accuracy [2].

Methodological Framework for Robust Signature Development

Computational Integration Strategies

Multi-omics integration employs distinct methodological approaches to combine data across biological layers:

Early Integration (Data-Level Fusion): Combines raw data from different omics platforms before statistical analysis. This approach preserves maximum information but requires careful normalization to handle different data types and scales. Methods include principal component analysis and canonical correlation analysis [3].

Intermediate Integration (Feature-Level Fusion): Identifies important features within each omics layer first, then combines these refined signatures for joint analysis. This balances information retention with computational feasibility and is particularly suitable for large-scale studies [3].

Late Integration (Decision-Level Fusion): Performs separate analyses within each omics layer and combines the resulting predictions using ensemble methods. This provides robustness against noise in individual omics layers and allows for modular analysis workflows [3].

Batch Effect Correction Methodologies

Addressing technical noise requires specific computational approaches:

Normalization Strategies: Sophisticated normalization is required to preserve biological signals while enabling cross-omics comparisons. Methods include quantile normalization, z-score standardization, and rank-based transformations, each with specific advantages for different data types [3].

Batch Effect Correction Algorithms: Tools like ComBat, surrogate variable analysis, and empirical Bayes methods effectively remove technical variation while preserving biological signals. The choice of algorithm depends on the nature of the batch effects and the data structure [1].

Advanced Machine Learning: Regularization techniques like elastic net regression, sparse partial least squares, and group lasso methods help identify robust biomarker signatures while avoiding overfitting in high-dimensional data [3].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Platforms for Reproducible Omics Studies

| Reagent/Platform Type | Specific Examples | Function in Signature Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Gene Expression Platforms | Affymetrix HG-U133A, Affymetrix HG-U133 Plus 2.0, Illumina HiSeq2000 | Enable cross-platform signature validation using different measurement technologies [2] |

| Normalization Algorithms | Robust Multi-array Average, Quantile Normalization, Z-score Standardization | Standardize data distributions across batches and platforms to reduce technical variance [2] [3] |

| Batch Effect Correction Tools | ComBat, Surrogate Variable Analysis, Empirical Bayes Methods | Identify and remove technical variations unrelated to biological signals [3] [1] |

| Multi-Omics Integration Platforms | mixOmics, MOFA, MultiAssayExperiment | Provide standardized frameworks for integrating data across different molecular layers [3] |

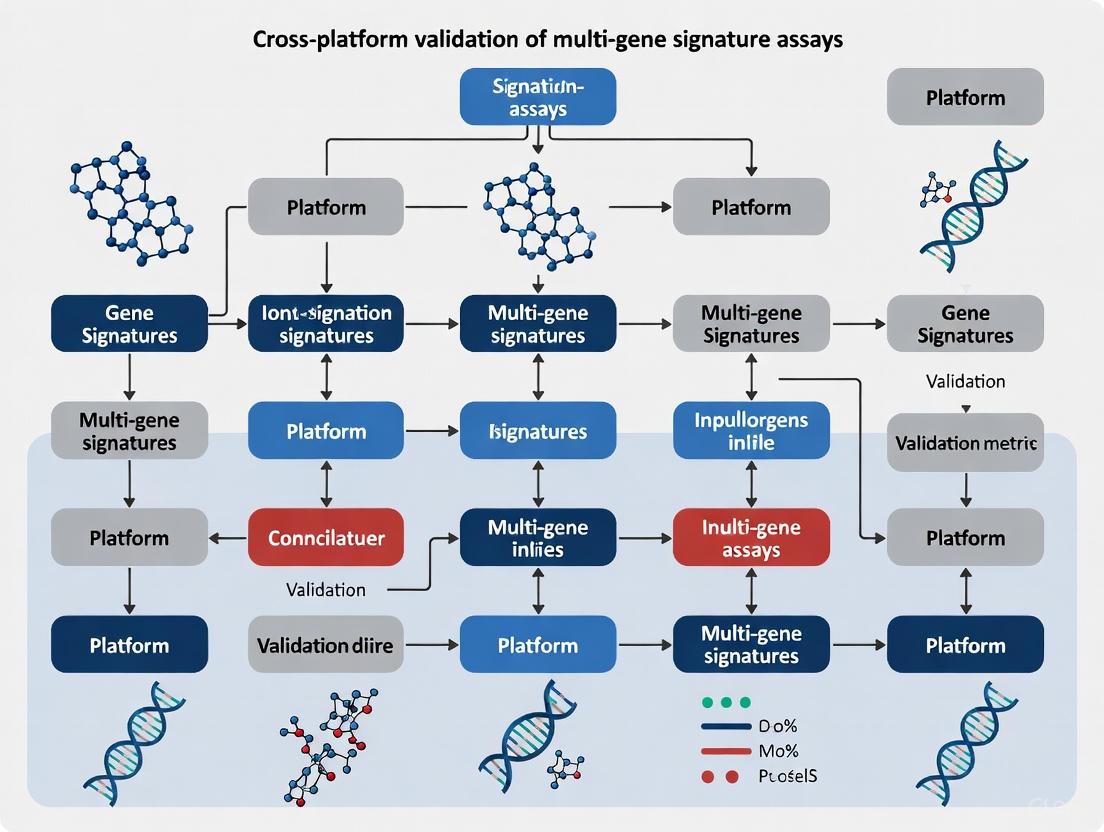

Visualizing the Validation Workflow and Challenge

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive validation workflow for developing robust omics signatures, highlighting critical stages where technical noise may be introduced and addressed.

Cross-Platform Signature Validation Workflow

The diagram above shows the sequential process for robust signature validation, with red dashed lines indicating points vulnerable to technical noise and green dashed lines showing where mitigation strategies are applied.

The challenge of batch effects is further illustrated by their diverse sources throughout the experimental process:

Sources of Technical Noise in Omics Studies

The problem of technical noise and limited reproducibility in omics signatures remains a significant challenge, but methodological advances in cross-platform validation offer promising solutions. The case study of the 14-gene glycolysis signature in LUAD demonstrates that robust, reproducible signatures can be achieved through multicenter study designs, cross-platform validation, and appropriate statistical methods addressing technical variability. As the field progresses, the integration of sophisticated batch correction algorithms, standardized analytical frameworks, and systematic validation across technologies will be essential for developing clinically applicable omics-based assays that reliably inform patient stratification and treatment decisions.

In the evolving field of precision medicine, model transferability refers to the ability of a predictive model to maintain its performance accuracy when applied across different technological platforms, experimental protocols, and patient populations without requiring retraining or significant modification [4] [5]. This capability is particularly crucial for molecular signatures derived from high-throughput omics technologies, which hold great promise for improving disease diagnosis, patient stratification, and treatment prediction in clinical settings [4]. The fundamental challenge in this domain stems from the observation that identical biological samples can yield different RNA quantification results when processed on different platforms, leading to reduced performance of any RNA-based diagnostic metric [4]. Despite considerable technological advancements and decades of research aimed at clinical application, a significant discrepancy persists between the abundance of published signatures and the limited number of validated, commercially available diagnostic tests based on host RNA molecules, attesting to the critical nature of the transferability problem [4].

The concept of platform independence, borrowed from computer science, describes systems that can operate across diverse environments without modification [6]. In computational contexts, platform independence is achieved through abstraction layers, virtual machines, and intermediate representations that separate application logic from underlying hardware specifics [6]. Similarly, in genomic medicine, platform-independent models must overcome technical variations between discovery platforms (e.g., RNA-Sequencing) and implementation platforms (e.g., clinical PCR-based assays) to deliver consistent predictions [4]. The Model-Driven Architecture framework formalizes this approach through transformation of Platform-Independent Models (PIM) to Platform-Specific Models (PSM), enabling adaptation to different technological constraints while preserving core functionality [7].

The Technical Foundations of Transferability Challenges

Fundamental Obstacles in Cross-Platform Implementation

The journey from biomarker discovery to clinical implementation faces several technical hurdles that undermine model transferability. High-throughput technologies like RNA-Sequencing, while instrumental in signature discovery, are unsuitable for routine clinical use due to their cost, turnaround time, and requirement for specialized equipment and personnel [4]. Consequently, measurement of gene expression must transition to more accessible platforms based on targeted nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs), such as real-time PCR (qPCR) or isothermal amplification methods like LAMP [4]. This transition introduces significant technical challenges because accurate quantification using NAATs relies on amplifying specific regions of target mRNA (amplicons) delineated by sequence-specific primers, which must meet rigorous biochemical and thermodynamic criteria including primer melting temperature, amplicon length, GC content, and specificity of primer binding [4].

These constraints may drastically limit the potential for certain transcripts to be included in a NAAT-based diagnostic test. For instance, designing reliable primers for an exon with unusually high GC content—even if it displays highly significant differential expression—can be challenging [4]. Furthermore, different implementation chemistries impose distinct constraints. LAMP assays typically require longer amplicons (200-250 base pairs) and more primers per target compared to PCR-based platforms, presenting different design limitations [4]. Additionally, each platform has its own dynamic range of quantification, affecting measurement precision across different expression levels [4]. Digital PCR generally provides higher quantification precision than qPCR, even for identical nucleic acid targets and molecular assays, further complicating cross-platform consistency [4].

Biological and Computational Complexities

Beyond technical platform differences, biological variability and computational approaches contribute to transferability challenges. Biological factors including genetic differences, disease heterogeneity, microbial interactions, and temporal variations in gene expression influenced by metabolic changes, drugs, and comorbidities all introduce variability that can reduce model performance in external validation studies [4]. From a computational perspective, traditional feature selection processes primarily utilize statistical and machine learning methodologies based on fold-change, p-values, or mean expression values, typically without accounting for constraints associated with cross-platform transfer [4]. This decoupling between signature discovery and implementation requirements represents a critical gap in current approaches [4].

Computational Frameworks for Platform-Independent Prediction

Emerging Computational Strategies

Several innovative computational frameworks have been developed to address transferability challenges in genomic medicine. The Cross-Platform Omics Prediction (CPOP) procedure represents a penalized regression model that uses omics data to predict patient outcomes in a platform-independent manner across time and experiments [5]. CPOP incorporates three distinct innovations: (1) using ratio-based features rather than absolute expression levels, (2) assigning feature weights proportional to between-data stability, and (3) selecting features with consistent effect sizes across multiple datasets in the presence of noise [5]. This approach differs fundamentally from methods that adjust all gene expressions by one or a group of control genes, instead examining all pairs of features to capture relative changes in gene expression systems, thereby reducing between-data variation [5].

The TimeMachine algorithm offers another approach for platform-independent circadian phase estimation from single blood samples [8]. This method introduces two normalization variants—ratio TimeMachine (rTM) and Z-score TimeMachine (zTM)—both requiring gene expression measurements for only 37 genes from a single blood draw and functioning across different assay technologies without constraints [8]. The algorithm identifies genes with robust cycling patterns as candidate phase markers, then applies either pairwise gene ratios or Z-score transformation to normalize data across platforms based on the concept that relative expression of predictor genes, rather than absolute magnitudes, represents the biologically relevant feature better preserved across platforms [8].

Model Adaptation Frameworks

Beyond purpose-built algorithms, generalized frameworks for model adaptation facilitate transferability. Research on Dynamic Bayesian Networks (DBN) demonstrates guidelines for transferring ecological models from generic contexts to specific applications [9]. This approach retains the general model structure while adapting conditional probability tables for nodes characterizing location-specific dynamics, leveraging expert knowledge to complement limited data [9]. Similarly, the Ciclops protocol provides a systematic approach for building models trained on cross-platform transcriptome data for clinical outcome prediction, though technical details are limited in the available reference [10].

In machine learning, the Task Conflict Calibration (TC2) method addresses transferability in self-supervised learning by alleviating task conflict through a factor extraction network that produces causal generative factors for all tasks and a weight extraction network that assigns dedicated weights to each sample [11]. This approach employs data reconstruction, orthogonality, and sparsity constraints to ensure learned features effectively generate causal factors suitable for multiple tasks, calibrated through a two-stage bi-level optimization framework [11].

Table 1: Comparison of Platform-Independent Prediction Frameworks

| Framework | Core Methodology | Key Innovations | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| CPOP [5] | Penalized regression with ratio-based features | Ratio-based features, between-data stability weighting, consistent effect size selection | Maintains prediction scale across platforms; comparable or superior to established signatures |

| TimeMachine [8] | Pairwise gene ratios or Z-score normalization | Single-sample requirement, minimal gene set (37 genes), no retraining needed | Median absolute error of 1.65-2.7 hours across platforms without renormalization |

| DBN Adaptation [9] | Structural retention with parameter adaptation | Expert knowledge integration, conditional probability table modification | Successful transfer of seagrass ecosystem models with limited data |

| TC2 [11] | Task conflict calibration with bi-level optimization | Factor extraction network, weight assignment, orthogonality constraints | Consistent transferability improvement across multiple downstream tasks |

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Transferability

Validation Methodologies for Cross-Platform Performance

Rigorous experimental protocols are essential for validating model transferability. The standard assessment approach involves constructing a model using one dataset (Dataset A) and applying it to a new dataset (Dataset B) to generate cross-data predicted outcomes, then comparing these results to the ideal scenario where a model built from Dataset B is applied to itself (within-data prediction outcome) [5]. A transferable model demonstrates minimal discrepancy between cross-data and within-data predictions, with results clustering around the identity line (y = x) on scatter plots [5].

For molecular signatures, an effective protocol involves developing a clinical-ready molecular assay using platforms like NanoString nCounter, which offers low per-assay cost and wide deployment capability [5]. This process includes constructing a gene set panel consisting of differentially expressed genes most strongly associated with the clinical outcome, plus housekeeping genes for normalization [5]. Direct comparison between data generated from the new platform and previously generated data from the discovery platform (e.g., Illumina cDNA microarray) should demonstrate high correlation of both gene expression values and log-fold-differences between prognostic groups [5].

The TimeMachine protocol employs a structured workflow comprising: (1) identification of predictor genes through JTK_Cycle analysis to select genes with robust cycling patterns; (2) sample-wise normalization using either pairwise gene ratios or Z-score transformation; and (3) application of the trained predictor to independent datasets with distinct experimental protocols and assay platforms without retraining or renormalization [8]. Performance is quantified using median absolute error between predicted and actual values across these independent validations [8].

Implementation Workflow for Cross-Platform Models

The transformation from platform-specific discovery to platform-independent implementation follows a structured workflow that embeds implementation constraints early in the biomarker discovery process [4]. This approach acknowledges that successful clinical translation requires consideration of the target platform during feature selection, not merely as a post-hoc validation step [4]. Key considerations include the maximal number of targets imposed by the chosen multiplexing strategy, biochemical constraints of the implementation chemistry, and the genomic context of identified RNA biomarkers [4].

Table 2: Experimental Protocols for Transferability Assessment

| Protocol Step | Platform-Specific Approach | Platform-Independent Approach | Key Differences |

|---|---|---|---|

| Feature Selection | Statistical significance (p-value, fold-change) | Stability across datasets, implementation constraints | Platform-independent embeds technical feasibility |

| Feature Engineering | Absolute expression values | Ratio-based features, Z-score normalization | Platform-independent uses relative expression |

| Model Training | Single dataset optimization | Multiple dataset integration with consistency weighting | Platform-independent prioritizes cross-dataset reproducibility |

| Validation | Within-dataset cross-validation | Cross-platform, cross-study validation | Platform-independent tests real-world conditions |

| Normalization | Batch correction, quantile normalization | Within-sample ratios, pre-trained transformations | Platform-independent avoids batch-specific adjustments |

Case Studies in Multi-Gene Signature Assays

Established Clinical Assays and Their Transferability Approaches

Several multi-gene expression assays have successfully navigated the path from discovery to clinical implementation, providing valuable insights into transferability strategies. The Oncotype DX breast cancer assay analyzes 21 genes to generate a recurrence score (0-100) that guides adjuvant therapy in early-stage, hormone receptor-positive, HER2-negative breast cancer [12]. This assay demonstrated transferability through validation in large prospective trials like TAILORx, which established that most patients with intermediate recurrence scores (11-25) could safely forego chemotherapy [12].

The MammaPrint 70-gene signature classifies breast cancer patients into low-risk and high-risk groups for distant metastasis across all breast cancer subtypes, regardless of ER, PR, or HER2 status [12]. Its transferability was established through the MINDACT trial, which validated its ability to identify patients with discordant clinical and genomic risk profiles who could safely omit chemotherapy [12]. The Prosigna assay utilizes a 50-gene signature to provide both a risk-of-recurrence score and intrinsic molecular subtype classification, employing novel digital counting technology to enhance reproducibility across settings [12].

These successful clinical assays share common strategies that enhance transferability: they utilize standardized, predefined gene sets; implement controlled measurement technologies; and have undergone validation in large, prospective, multi-center trials that explicitly assess performance across different clinical settings [12].

Comparative Performance in Practical Applications

In comparative studies, platform-independent methods demonstrate distinct advantages in real-world applications. For melanoma prognosis prediction, CPOP showed significantly improved transferable performance compared to traditional Lasso regression [5]. While Lasso exhibited substantial scale differences between cross-platform and within-platform predictions, CPOP produced predicted probabilities essentially identical to desired within-data prediction outcomes, with maintained hazard ratio concordance across independent validation datasets [5].

For circadian phase estimation, TimeMachine achieved median absolute errors of 1.65 to 2.7 hours across four distinct datasets with different microarray and RNA-seq platforms, without requiring renormalization or retraining [8]. This performance was comparable to methods requiring two samples per subject, despite using only a single blood draw [8]. The algorithm's accuracy persisted regardless of systematic differences in experimental protocol and assay platform, enabling flexible application to both new samples and existing data without technology limitations [8].

In lung adenocarcinoma prognosis, an 8-gene signature identified through systems biology approaches demonstrated comparable or superior predictive power to established signatures (Shedden, Soltis, and Song) while using significantly fewer transcripts [13]. The signature employed equal-weight gene ratios with opposing correlations to survival, revealing additive or synergistic predictive value that achieved an average AUC of 75.5% across three timepoints [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful development of platform-independent models requires specialized research reagents and computational tools that facilitate cross-platform validation.

Table 3: Essential Research Resources for Transferability Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function in Transferability Research |

|---|---|---|

| Multi-Platform Profiling Technologies | NanoString nCounter, RNA-Seq, Microarrays | Generate cross-platform data for model development and validation |

| Computational Frameworks | CPOP, TimeMachine, Ciclops | Implement platform-independent algorithms and validation protocols |

| Reference Datasets | TCGA, GEO Accessions (GSE39445, GSE48113) | Provide benchmark data for cross-platform performance assessment |

| Bioinformatic Tools | WGCNA, JTK_Cycle, limma | Enable feature selection, network analysis, and rhythm detection |

| Clinical Validation Resources | Prospective trial data, Independent cohorts | Assess real-world performance across diverse patient populations |

The evolution from platform-specific to platform-independent prediction models represents a critical frontier in precision medicine. Current evidence demonstrates that successful transferability requires embedding implementation constraints early in the discovery process, rather than treating them as validation considerations [4]. Approaches utilizing ratio-based features [5] [8], within-sample normalization [8], and cross-dataset stability weighting [5] have shown promising results in maintaining performance across technological platforms.

The future trajectory of this field points toward increased integration of multi-omics data, development of novel predictive assays, and expansion of validation in diverse populations [12]. Furthermore, methodological advances from machine learning, particularly techniques addressing task conflict and domain adaptation [11], offer promising avenues for enhancing model transferability. As these approaches mature, they hold the potential to bridge the persistent gap between biomarker discovery and clinical implementation, ultimately fulfilling the promise of precision medicine for broader patient populations.

The advent of multigene signature assays has revolutionized prognostic stratification and treatment guidance in oncology, particularly for complex malignancies like melanoma and breast cancer. These assays quantify the expression levels of specific gene panels to generate scores that predict clinical outcomes such as disease recurrence, survival, and response to therapy. However, the translational pathway from signature discovery to clinical implementation is fraught with a critical challenge: limited cross-platform transferability. When signatures developed on one measurement platform (e.g., microarrays) fail to validate on another (e.g., RT-PCR or RNA-Seq), the clinical consequences can be significant, potentially leading to misinformed treatment decisions.

This guide objectively compares the performance and clinical impact of multigene signatures in melanoma and breast cancer, focusing on the repercussions of their platform dependence. We present experimental data and case studies that underscore the imperative for robust cross-platform validation to ensure that these powerful molecular tools deliver reliable, actionable information in diverse clinical settings.

Comparative Analysis of Signature Performance and Clinical Utility

Table 1: Comparison of Multigene Signature Applications in Melanoma and Breast Cancer

| Feature | Melanoma | Breast Cancer |

|---|---|---|

| Key Signatures | Immune-related prognostic signature [14], anti-PD-1 response model [15], irAE predictive signature [16] | 70-gene, 21-gene Recurrence Score (RS), Genomic Grade Index (GGI), PAM50 [17] |

| Primary Clinical Use | Predicting overall survival, response to immunotherapy (anti-PD-1), risk of immune-related adverse events [14] [15] [16] | Prognostication in older patients (≥70 years), guiding adjuvant chemotherapy decisions [17] |

| Consequence of Non-Transferability | Incorrect risk stratification leading to under-/over-treatment; failure to identify patients likely to benefit from or experience toxicity from ICB [14] [16] [15] | Loss of prognostic power, potentially withholding beneficial therapy or administering unnecessary chemotherapy to older patients [17] |

| Technical Validation Evidence | Immune-related risk model built on TCGA data required normalization against GTEx database [14]; Multi-platform RNA hybridization showed bilinear signal relationship [18] | Research versions of signatures applied across 39 datasets; coverage of 70-gene signature was 91% on non-native platforms [17] |

Table 2: Quantitative Impact of Signature Implementation on Clinical Outcomes

| Cancer Type | Signature Name/Type | Impact on Clinical Outcome | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Melanoma | 91-gene immune-related risk model | High risk score correlated with poorer overall survival and higher AJCC-TNM stages [14] | P < 0.01 |

| Melanoma | Integrative model for anti-PD-1 response | Predicts intrinsic resistance to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy [15] | Validated in independent cohorts |

| Melanoma | Gene signature for irAEs | Predicted occurrence and timing of immune-related adverse events [16] | No events in low-risk signature patients |

| Breast Cancer | 70-gene signature in ER+/LN- patients (≥70 yrs) | Provided significant prognostic information [17] | Log-rank P ≤ 0.05; significant in multivariable analysis |

| Breast Cancer | 21-gene RS in ER+/LN- patients (≥70 yrs) | Prognostic capacity was not retained in multivariable analysis [17] | Not significant in multivariable analysis |

Melanoma Case Study: Immune Signatures and Immunotherapy

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

A 2021 study investigated immune-related signatures and immune cell infiltration in melanoma using the following detailed methodology [14]:

- Data Acquisition: Transcriptome profiling and clinical data for melanoma were downloaded from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), encompassing 471 tumor samples. Matched normal samples were obtained from the Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) database.

- Data Processing: Genome expression data were merged and normalized using the

limmapackage in R. This step is critical for reducing technical variance before comparative analysis. - Gene Identification: Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between tumor and normal samples were screened. These were cross-referenced with an immune-related gene list from the InnateDB database to identify 91 differentially expressed immune-related signatures.

- Functional & Prognostic Analysis: Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analyses were performed. A risk model was constructed using univariate and multivariate Cox regression, along with LASSO analysis, to identify hub genes prognostic for overall survival.

- Immune Infiltration Correlation: The association between the risk score and immune cell infiltration was evaluated using the CIBERSORT algorithm and TIMER database, comparing immune cell densities between high- and low-risk groups.

The workflow for this analysis is summarized in the following diagram:

Clinical Consequences and Research Reagents

The study found that a high-risk score derived from the immune signature was a powerful indicator of poorer overall survival and correlated significantly with higher American Joint Committee on Cancer-TNM stages and advanced pathological stages. Furthermore, the high-risk group exhibited a significantly lower infiltration density of specific immune cells, notably M0 macrophages and activated mast cells [14]. This model, if not properly validated across platforms, could fail to identify these high-risk patients, preventing them from receiving more intensive monitoring or novel therapeutic interventions.

Another critical application in melanoma is predicting response to Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors (ICI) and their associated toxicities. A 2024 study identified a whole-blood gene-expression signature predictive of immune-related adverse events (irAEs) in patients treated with anti-PD-1 inhibitors [16]. The protocol involved:

- Sample Collection: Baseline peripheral blood samples collected prior to ICI treatment.

- RNA Extraction: Using the QIAamp RNA Blood Mini Kit (Qiagen).

- Gene Expression Profiling: Using the NanoString nCounter PanCancer IO 360 panel (770 genes).

- Data Normalization & Analysis: Normalization with nSolver software and identification of predictive signatures via cross-validated sparse partial least squares modeling.

The study found that distinct gene signatures could predict the occurrence and timing of specific irAEs, such as arthralgia and colitis. Crucially, no events were observed in patients classified as "low-risk" by the signature over the follow-up period [16]. A non-transferable signature here could misclassify a patient's risk, leading to inadequate monitoring for severe toxicities or, conversely, excessive caution in patients unlikely to experience irAEs.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Melanoma Signature Analysis

| Reagent/Kit | Specific Function | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| QIAamp RNA Blood Mini Kit (Qiagen) | Extraction of high-quality RNA from whole-blood samples. | Used in studies predicting irAEs to ensure intact RNA for downstream profiling [16]. |

| NanoString nCounter PanCancer IO 360 Panel | Multiplexed digital quantification of 770 immune and cancer-related genes without amplification. | Employed for its high sensitivity with FFPE-derived RNA and ability to work with degraded samples [19] [16]. |

| RNeasy FFPE Kit (Qiagen) | Isolation of RNA from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue blocks. | Key for utilizing archived clinical specimens with variable RNA quality [19]. |

| CIBERSORT Algorithm | Computational deconvolution of immune cell fractions from bulk tumor gene expression data. | Used to correlate gene signature risk scores with the tumor immune microenvironment [14]. |

Breast Cancer Case Study: Prognostication in Older Patients

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

The clinical utility of gene signatures in older breast cancer patients (≥70 years) has been controversial. A comprehensive 2024 study directly addressed this gap by performing a multi-signature comparison [17]. The experimental protocol was as follows:

- Cohort Assembly: Data was extracted from the

MetaGxBreastR package, a database of 39 open-access breast cancer datasets totaling 9,583 patients. After filtering for age ≥70 years, and the presence of ER and survival data, 871 patients remained. - Signature Application: Research versions of six clinically relevant signatures were applied to each dataset: Genomic Grade Index (GGI), 70-gene signature, 21-gene Recurrence Score (RS), Cell Cycle Score (CCS), PAM50 Risk-of-Recurrence Proliferation (ROR-P), and PAM50.

- Cross-Platform Mapping: Probe-to-gene mapping was achieved by merging annotation sources. A major technical consideration was that the 70-gene signature, derived on an Agilent platform, had only ~75% of its genes mappable to the Affymetrix platforms common in the merged datasets. Datasets with less than 75% coverage for any signature were excluded.

- Statistical Analysis: Prognostic capacity was tested using Kaplan-Meier analysis and multivariable Cox-proportional hazard models, adjusting for clinical variables like ER status, lymph node status, tumor grade, and size.

The analysis workflow and key finding are depicted below:

Clinical Consequences and Research Reagents

The study yielded nuanced results with direct clinical implications. In the ER-positive, lymph-node-negative (ER+/LN-) subgroup of older patients, all signatures except the 21-gene Recurrence Score (RS) were significant in Kaplan-Meier analysis. However, in the more rigorous multivariable analysis, only the 70-gene, CCS, ROR-P, and PAM50 signatures retained independent prognostic significance [17]. This highlights a critical consequence of signature performance: a clinician using the RS score in this specific population might find it lacks independent prognostic power, potentially leading to uncertainty in chemotherapy decisions.

The technical hurdle of gene coverage (e.g., 91% for the 70-gene signature on non-native platforms) underscores the transferability problem. If a signature's key genes are not reliably measured on a new platform, its predictive power diminishes, risking the misclassification of a patient's recurrence risk. For older patients, who are often underrepresented in clinical trials and may be more vulnerable to treatment side effects, this could result in either the administration of unnecessary and toxic chemotherapy or the withholding of a potentially curative treatment.

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Breast Cancer Signature Analysis

| Reagent/Resource | Specific Function | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| MetaGxBreast R Package | A manually curated database of breast cancer gene expression datasets with standardized clinical metadata. | Provided the foundational data for large-scale, cross-study validation of signatures in a specific age subgroup [17]. |

| BRB ArrayTools | Integrated software for the comprehensive analysis of microarray gene expression data. | Used for normalizing compiled datasets from multiple sources in cross-platform meta-analyses [20]. |

| Probe-to-Gene Mapping Resources (e.g., Bioconductor) | Bioinformatics tools for accurately matching gene expression probes from different platforms to universal gene identifiers. | Essential for merging and analyzing data from diverse microarray platforms (e.g., Affymetrix, Agilent) [17] [18]. |

Cross-Platform Validation Strategies

The case studies above illustrate the pervasive challenge of platform dependency. Research shows that gene expression readings from different platforms (e.g., Affymetrix vs. Illumina microarrays) are not directly comparable due to differences in probe technology and targeted regions, resulting in a bilinear relationship of signal values [18]. A proposed computational framework aims to address this by embedding cross-platform implementation constraints directly into the signature discovery process. This includes considering the technical limitations of the target clinical platform (e.g., a multiplexed nucleic acid amplification test) during the initial bioinformatic selection of biomarker genes [21].

A successful example from neuroblastoma research demonstrates that a 42-gene prognostic signature, discovered using microarrays, was successfully transferred to the NanoString nCounter platform using RNA from FFPE tissues. This cross-platform validation confirmed the signature's power to stratify high-risk patients into "ultra-high-risk" and lower-risk groups with significantly different overall survival [19]. This validation step is essential for clinical deployment.

Multigene signatures offer tremendous potential for personalizing cancer management in both melanoma and breast cancer. However, their clinical utility is critically dependent on robust performance across the different technology platforms used in discovery versus routine clinical labs. The case studies presented here demonstrate that non-transferable signatures can have direct consequences: inaccurate prognostic stratification, flawed prediction of response to powerful immunotherapies, and an inability to anticipate serious treatment-related toxicities. To ensure that these sophisticated molecular tools benefit all patients, future research must prioritize cross-platform validation as a non-negotiable step in the development pipeline.

The Promise of Cross-Platform Validated Assays for Multi-Center and Prospective Studies

The identification of robust biomarkers and multi-gene signatures represents a cornerstone of modern precision medicine, enabling improved disease diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment selection. However, the transition of these molecular signatures from research discoveries to clinically applicable tools requires rigorous validation across multiple laboratory settings and technology platforms. Cross-platform validation ensures that assay results remain consistent and reproducible regardless of the specific instrumentation, laboratory environment, or technical personnel involved, thereby establishing the reliability necessary for multi-center studies and eventual clinical implementation.

Mounting evidence indicates that variability in performance between technology platforms significantly contributes to the lack of consensus and replicability in the biomarker literature [22]. This is particularly problematic for measurements of low-abundance analytes such as cytokines, which require highly sensitive technologies for accurate detection [22]. Similar challenges affect gene expression signatures developed for cancer classification and prognosis, where differences in sample processing, sequencing platforms, and analytical pipelines can substantially impact results. Consequently, comprehensive cross-platform evaluations are essential for identifying best-in-class technologies that deliver high performance, scalability, and reproducibility for biomarker discovery and development.

Comparative Platform Performance: Quantitative Metrics for Informed Selection

Comprehensive cross-platform comparisons provide critical empirical data to guide researchers in selecting optimal technologies for their specific applications. These evaluations typically assess multiple analytical parameters including sensitivity, precision, dynamic range, and correlation between platforms.

Immunoassay Platform Comparison

A comprehensive evaluation of five leading immunoassay platforms highlights the substantial variability in performance that can significantly impact research findings and their interpretation [22]. The study compared platform performance using serum and plasma samples from healthy controls and clinical populations (post-traumatic stress disorder and Parkinson's disease), focusing on cytokines implicated in both conditions (IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, and IFN-γ) [22].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Leading Immunoassay Platforms for Cytokine Detection

| Platform (Vendor) | Sensitivity (FEAD) | Precision (%CV) | Cross-platform Correlation | Best Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simoa (Quanterix) | Highest across all analytes | <20% across all samples | Strong for IL-6 (r=0.59-0.86) | Low-abundance cytokines |

| MESO V-Plex (Mesoscale Discovery) | Variable | Variable across cytokines | Strong for IL-6 (r=0.59-0.86) | Moderate abundance targets |

| Luminex (R&D Systems) | Variable | Variable across cytokines | Strong for IL-6 (r=0.59-0.86) | Multiplex panels |

| Quantikine ELISA (R&D Systems) | Variable | Variable across cytokines | Strong for IL-6 (r=0.59-0.86) | Single-analyte quantification |

| Luminex xMAP (Myriad) | Low across all analytes | Could not be assessed | Low correlation for other cytokines | Not recommended for low-abundance targets |

The study revealed that the single molecule array (Simoa) ultra-sensitive platform demonstrated superior sensitivity in detecting endogenous analytes across all clinical populations, as reflected by the highest frequency of endogenous analyte detection (FEAD) [22]. Additionally, Simoa showed high precision with less than 20 percent coefficient of variance (%CV) across replicate runs for samples from healthy controls, PTSD patients, and PD patients [22]. In contrast, other platforms exhibited more variable performance both in terms of sensitivity and precision [22].

For cross-platform correlation, IL-6 measurements showed the strongest correlations across all platforms except Myriad's Luminex xMAP, with correlation coefficients ranging from 0.59 to 0.86 [22]. However, for other cytokines including IL-1β, TNF-α, and IFN-γ, there was low to no correlation across platforms, indicating that reported measurements varied substantially depending on the assay used [22].

Genomic Assay Validation

Similar validation approaches are critical for genomic assays, particularly those intended for clinical applications. The Rapid-CNS2 platform for molecular profiling of central nervous system tumors exemplifies a comprehensively validated genomic assay [23]. This adaptive-sampling-based nanopore sequencing workflow was validated in a multicenter setting on 301 archival and prospective samples, including 18 samples sequenced intraoperatively [23].

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Rapid-CNS2 Platform for CNS Tumor Profiling

| Parameter | Performance Metric | Clinical Relevance |

|---|---|---|

| Turnaround Time | 30-min intraoperative window; 24h comprehensive profiling | Enables intraoperative decision-making |

| SNV Concordance | 91.67% with matched NGS panel data | Accurate mutation detection |

| IDH1/2 and BRAF Mutation Detection | 97.9% sensitivity, 100% specificity | Therapeutically relevant alterations |

| MGMT Promoter Methylation | 90.4% concordance with established methods | Predictive biomarker for treatment response |

| Copy Number Variation | Complete agreement with methylation array data | Diagnostic and prognostic utility |

| Methylation Family Classification | 92.9% correct assignment (99.6% with MNP-Flex) | WHO-compatible integrated diagnosis |

The validation demonstrated that Rapid-CNS2 accurately called 91.67% of single nucleotide variants identified by next-generation sequencing panel data, with a minimum on-target coverage of 10X required to achieve more than 90% concordance in mutation calls [23]. For therapeutically relevant alterations in IDH1/2 and BRAF, the platform demonstrated 97.9% sensitivity and 100% specificity [23]. The entire pipeline achieved an average turnaround time of 2 days from tissue receipt to complete report compared to an average of 20 days for conventional workflows, with the potential to reduce this to 40 hours after subtracting logistical delays [23].

Experimental Protocols for Cross-Platform Validation

Robust cross-platform validation requires carefully designed experiments that assess multiple performance parameters using clinically relevant samples. The following methodologies represent best practices derived from published validation studies.

Sample Selection and Preparation

Cross-platform comparisons should utilize samples from both healthy controls and relevant clinical populations to assess performance across the intended spectrum of applications [22]. For the immunoassay comparison, researchers used plasma and serum samples from individuals with PTSD (n=13) or Parkinson's Disease (n=14) as well as healthy controls (n=5) [22]. This approach ensures that platform performance is evaluated under conditions that reflect real-world research scenarios, particularly for low-abundance analytes that may be challenging to detect in healthy populations but clinically relevant in disease states.

Each vendor received identical sets of plasma and serum samples that had undergone the same number of freeze-thaw cycles to eliminate pre-analytical variables [22]. This standardized approach ensures that observed differences reflect true platform performance rather than sample handling artifacts.

Assessment of Analytical Parameters

Comprehensive validation should evaluate multiple analytical parameters that collectively determine assay utility:

- Sensitivity/Frequency of Endogenous Analyte Detection (FEAD): The proportion of samples in which the endogenous analyte is detected above the lower limit of quantification [22]. This parameter is particularly important for low-abundance biomarkers.

- Precision: Measured as the coefficient of variance (%CV) across replicate runs for samples from different populations [22]. Precision should be consistent across sample types and concentrations.

- Cross-platform Correlation: Correlation coefficients between measurements obtained from different platforms for the same samples [22]. Strong correlations indicate that different platforms yield comparable results, though systematic biases may still exist.

- Dynamic Range and Linearity: Assessed using serial dilution series to evaluate parallelism in measurement of cytokines or other analytes across different concentrations [22].

- Concordance with Established Methods: For genomic assays, this includes concordance with orthogonal methods such as NGS panels, methylation arrays, and immunohistochemistry for relevant biomarkers [23].

Multicenter Validation Design

Multicenter validation is essential to assess platform performance across different laboratory environments and operators. The Rapid-CNS2 validation was run independently at two centers (University Hospital Heidelberg, Germany and University of Nottingham, United Kingdom) on fresh or cryopreserved tumor tissue [23]. This approach provides critical data on real-world performance and identifies potential center-specific effects that could impact results in broader implementations.

Visualizing Cross-Platform Validation Workflows

The cross-platform validation process involves multiple stages from experimental design to data analysis and interpretation. The following diagram illustrates the key steps in a comprehensive validation workflow:

Cross-Platform Validation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Implementing robust cross-platform validation requires specific reagents, technologies, and computational tools. The following table details key solutions used in the featured validation studies:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Cross-Platform Validation

| Category | Specific Solution | Function in Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Immunoassay Platforms | Simoa, MESO V-Plex, Luminex xMAP, Quantikine ELISA | Quantification of protein biomarkers with varying sensitivity requirements |

| Genomic Profiling | Rapid-CNS2, NanoString nCounter, Methylation Arrays | Nucleic acid analysis, gene expression profiling, methylation classification |

| Reference Materials | Certified Reference Materials, Pooled Control Sera | Standardization across platforms and laboratories |

| Bioinformatics Tools | MNP-Flex Classifier, Eval Package, Custom Scripts | Data analysis, classification, and performance evaluation |

| Quality Control Metrics | Coefficient of Variance (CV), Frequency of Endogenous Analyte Detection (FEAD), Concordance Rates | Standardized assessment of platform performance |

The Lymphoma Expression Analysis (LExA120) 120 gene expression panel developed for the NanoString platform exemplifies a modular approach to assay validation, targeting 95 genes and 25 housekeeping genes to evaluate aggressive B-cell lymphomas [24]. This panel demonstrated high concordance with previously validated methods according to Pearson correlation coefficients of the signature scores, along with high reproducibility in repeated tests and across different clinical laboratories [24].

For methylation-based classification, the development of MNP-Flex, a platform-agnostic methylation classifier encompassing 184 classes, addresses the critical need for standardized classification across different technologies [23]. This classifier achieved 99.6% accuracy for methylation families and 99.2% accuracy for methylation classes with clinically applicable thresholds across a global validation cohort of more than 78,000 frozen and formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded samples spanning five different technologies [23].

Implications for Multi-Center and Prospective Studies

Cross-platform validated assays offer significant advantages for multi-center and prospective studies by ensuring consistency and comparability of data across different research sites and over time. The ability to obtain consistent results regardless of the testing location is fundamental to the success of large-scale collaborative research initiatives and clinical trials.

Validated modular platforms like the LExA120 panel enable rapid, cost-effective molecular classification that can be implemented across multiple laboratory settings without sacrificing accuracy [24]. Similarly, platform-agnostic classifiers like MNP-Flex allow different centers to utilize locally available technologies while still generating comparable results [23]. This flexibility is particularly valuable in global research collaborations where access to specific technologies may vary.

For prospective studies, the reduced turnaround time demonstrated by platforms like Rapid-CNS2 (40 hours compared to several weeks for conventional workflows) enables more rapid clinical decision-making while maintaining diagnostic accuracy [23]. This combination of speed, accuracy, and reproducibility makes cross-platform validated assays particularly valuable for time-sensitive clinical applications and interventional trials.

Cross-platform validation represents an essential step in the translation of biomarker discoveries from research tools to clinically applicable assays. Comprehensive comparisons of leading technologies demonstrate that platform choice significantly impacts reported results, particularly for low-abundance analytes. The emerging generation of validated, platform-agnostic assays and classifiers offers unprecedented opportunities for multi-center collaborations and prospective studies by ensuring consistent performance across different laboratory environments and technologies. By prioritizing cross-platform validation during assay development, researchers can enhance the reproducibility, reliability, and clinical utility of molecular signatures in precision medicine.

Innovative Computational and Statistical Frameworks for Cross-Platform Modeling

In the evolving field of precision medicine, gene expression signatures hold tremendous promise for improving disease diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment selection. However, a significant challenge hindering their clinical implementation is the lack of transferability across different measurement platforms. Cross-platform validation of multi-gene signature assays is essential for transforming research discoveries into clinically applicable tools. The Cross-Platform Omics Prediction (CPOP) procedure emerges as a sophisticated statistical machine learning framework specifically designed to overcome technical variations between platforms, enabling robust prediction models that perform consistently across diverse datasets [5].

CPOP addresses a critical limitation in molecular signature development: the inability of models trained on one platform (e.g., microarrays) to maintain accuracy when applied to data from another platform (e.g., RNA-sequencing or targeted assays). This transferability challenge stems from technical noise, batch effects, and platform-specific variations that create substantial data scale differences [5] [25]. By employing innovative ratio-based features and consensus selection methods, CPOP represents a significant advancement toward reliable biomarker implementation in multi-center and prospective clinical settings.

Comparative Analysis: CPOP Versus Alternative Approaches

Methodological Comparison

Table 1: Key methodological differences between CPOP and alternative approaches

| Feature | CPOP | Traditional Gene-Based Models | Rank-Based Methods (singscore) | Platform-Specific Signatures |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feature Type | Ratio-based (pairwise differences) | Absolute gene expression values | Gene rank positions | Absolute gene expression values |

| Platform Independence | High - Designed for cross-platform use | Low - Platform-specific normalization needed | Moderate - Rank preserved but information loss | None - Tied to specific platform |

| Normalization Requirements | Minimal - No re-normalization of new data required | Extensive - Requires batch correction and scale adjustment | Moderate - Requires consistent gene sets | Extensive - Platform-specific protocols |

| Data Requirements | Preferably two training datasets from different sources | Single training dataset | Single sample or cohort | Single platform data |

| Feature Selection | Considers effect size consistency across datasets | Within-dataset performance only | Pre-defined gene sets | Within-platform performance |

Performance Comparison

Table 2: Experimental performance comparisons across methodologies

| Method | Prediction Consistency | Melanoma Validation (Hazard Ratio Concordance) | Implementation Complexity | Clinical Translation Potential |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPOP | High - Stable across platforms [5] | High correlation between cross-data and within-data predictions [5] | Moderate - Requires specialized statistical implementation | High - Designed for clinical deployment |

| Lasso Regression | Low - Significant scale differences between platforms [5] | Poor transferability with scale discrepancies [5] | Low - Standard implementation | Low - Platform-specific retraining needed |

| nCounter with Correlation | Moderate - Platform transfer possible with same genes [19] | Not specifically reported | Low - Commercial system with built-in analysis | Moderate - FDA-cleared platform available |

| singscore | Moderate - Rank-based approach preserves order [26] | High correlation for immune signatures (Spearman IQR: 0.88-0.92) [26] | Low - Straightforward rank calculation | Moderate - Limited by pre-defined gene sets |

Core CPOP Methodology and Experimental Protocols

The CPOP Workflow

The CPOP procedure employs a sophisticated multi-step workflow that transforms traditional predictive modeling through ratio-based feature engineering and cross-dataset validation.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Feature Construction Protocol

The foundational innovation of CPOP lies in its ratio-based feature construction, which converts absolute gene expression values into stable relative measures:

Input Requirements: CPOP requires two training datasets (x1, x2) with corresponding response variables (y1, y2), preferably from different platforms or sources [25] [27]. The gene expression data should already be logarithmically transformed to handle large magnitude differences.

Pairwise Difference Calculation: For each dataset, CPOP computes all pairwise differences between genes using the

pairwise_col_difffunction. Mathematically, this is represented as:z1 = x1_i - x1_jfor all i ≠ j, which corresponds tolog(A/B)in the original scale [27]. This transformation captures relative gene expression changes rather than absolute values.Feature Matrix Generation: The output is a new matrix where columns represent gene-gene ratios (e.g., "GeneA--GeneB") rather than individual genes. This creates a substantially larger feature space but with enhanced cross-platform stability.

Feature Selection and Model Building Protocol

CPOP implements a specialized regularized regression framework that prioritizes cross-dataset consistency:

Stability-Weighted Selection: The

cpop_modelfunction applies Elastic Net regularization (withalphaparameter controlling Lasso vs. Ridge balance) while incorporating weights proportional to each feature's between-dataset stability [5] [27].Iterative Feature Reduction: The procedure iteratively selects features based on model fit until reaching a pre-determined number of features (

n_featuresparameter). At each iteration, features are evaluated for predictive performance across both datasets.Effect Size Consistency Filtering: Candidate features are further filtered to retain only those with consistent effect sizes (coefficient signs and magnitudes) across both training datasets. This critical step ensures biological reproducibility beyond statistical association [5].

Validation and Performance Assessment Protocol

Comprehensive validation is essential for demonstrating cross-platform utility:

Cross-Data Prediction Assessment: Researchers apply the CPOP model trained on dataset A to dataset B, comparing these "cross-data predicted outcomes" to ideal "within-data predictions" where models are trained and tested on the same dataset [5].

Hazard Ratio Concordance: For survival outcomes, hazard ratios from cross-data predictions are compared to within-data hazard ratios. A transferable model demonstrates high correlation between these estimates.

Independent Cohort Validation: Final validation should include application to completely independent datasets not involved in model development, assessing real-world performance without any retraining or renormalization.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key research reagents and computational tools for CPOP implementation

| Category | Specific Items | Function in CPOP Research | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wet-Lab Platforms | NanoString nCounter Platform | Targeted gene expression quantification for clinical assay development [5] [19] | Enables FFPE-compatible clinical-ready assays with 100-200 gene panels |

| Illumina Microarrays | Genome-wide expression profiling for discovery phase | Provides comprehensive discovery data but with platform-specific biases | |

| RNA-Sequencing | Whole transcriptome analysis for signature discovery | Requires careful probe mapping for cross-platform application | |

| Computational Tools | R Statistical Environment | Primary implementation platform for CPOP methodology | Essential for statistical analysis and model building |

| CPOP R Package | Dedicated implementation of CPOP algorithm [27] | Provides cpop_model, pairwise_col_diff, and visualization functions |

|

| glmnet Package | Elastic Net regularization implementation | Backend for CPOP's regularized regression | |

| Sample Types | FFPE Tumor Samples | Clinically relevant sample source for validation [19] [26] | Requires specialized RNA isolation kits (e.g., Qiagen RNeasy FFPE) |

| Fresh Frozen Tissue | Higher quality RNA for discovery phases | Enables more comprehensive transcriptomic profiling | |

| Reference Materials | Housekeeping Genes | Normalization controls (e.g., GAPDH, ACTB) [19] | Critical for technical variation adjustment in targeted assays |

Conceptual Framework for Cross-Platform Prediction

The theoretical foundation of CPOP addresses fundamental challenges in omics data integration, particularly the systematic technical variations that confound biological signals.

Application Evidence and Validation Studies

Melanoma Prognosis Prediction

The original CPOP demonstration focused on stage III melanoma prognosis using transcriptomics data. Researchers developed a clinical-ready 186-gene panel on the NanoString platform, validating against previous microarray data from the same cohort [5]. The CPOP model achieved stable prediction performance across MIA-Microarray, MIA-NanoString, TCGA, and Sweden datasets, with significantly improved transferability compared to standard Lasso regression [5].

Radiation Dosimetry Reconstruction

In radiation biology, CPOP principles were applied to develop a mouse blood gene signature for quantitative radiation dose reconstruction. Researchers identified 30 radiation-responsive genes from microarray datasets, then validated a refined 7-transcript signature using qRT-PCR in an independent mouse cohort [20]. The cross-platform implementation achieved dose reconstruction with root mean square error of ±1.1 Gy, demonstrating quantitative prediction transferability.

Immunotherapy Response Prediction

A rank-based scoring approach (singscore) demonstrated complementary cross-platform utility in advanced melanoma patients treated with immunotherapy. Researchers achieved highly correlated signature scores (Spearman correlation IQR 0.88-0.92) between NanoString and whole transcriptome sequencing platforms [26]. This validation across targeted and comprehensive transcriptomic platforms highlights the broader ecosystem of cross-platform methodologies.

Implementation Considerations and Limitations

While CPOP offers significant advantages for cross-platform prediction, researchers should consider several practical aspects:

Dimensionality Management: CPOP is not intended for full-scale RNA-Sequencing data with >1,000 features. Optimal application requires pre-selection of candidate biomarkers to 100-200 genes, typically through univariate screening or literature curation [25].

Data Requirements: The method optimally performs with two training datasets from different sources, which may not always be available. With single dataset training, some benefits of cross-dataset consistency filtering are lost.

Computational Intensity: The pairwise difference calculation creates O(p²) features from p original genes, increasing computational requirements. For 200 genes, this generates approximately 20,000 ratio features.

Biological Interpretation: Ratio-based features (GeneA--GeneB) require different interpretation approaches than individual gene features, though network visualization tools in the CPOP package help address this challenge [27].

The CPOP procedure represents a significant methodological advancement in cross-platform validation of multi-gene signature assays. By leveraging ratio-based features, stability-weighted selection, and effect size consistency filtering, CPOP directly addresses the fundamental transferability challenge that has hindered clinical implementation of omics-based predictors.

Experimental validations across multiple disease contexts—including melanoma prognosis, radiation dosimetry, and immunotherapy response—demonstrate CPOP's ability to maintain predictive performance across measurement platforms without requiring data renormalization. While alternative approaches like rank-based methods offer complementary strengths, CPOP's integrated framework provides a comprehensive solution for developing clinically implementable molecular signatures.

As precision medicine continues to evolve, methodologies like CPOP will be essential for translating high-throughput omics discoveries into robust clinical tools that perform reliably across diverse healthcare settings and measurement platforms.

Subtype Correlation (subC) and Mechanism-of-Action (MOA) Modeling for Predictive Signatures

Predictive gene expression signatures are powerful tools in precision oncology, enabling the stratification of patients based on their likely response to specific therapies. Unlike purely prognostic signatures, which predict outcome under a single treatment regimen, predictive signatures estimate differential survival outcomes between different drug regimens, providing a critical criterion for treatment optimization [28]. Two advanced methodological frameworks for constructing such predictive signatures are Subtype Correlation (subC) and Mechanism-of-Action (MOA) modeling. The subC approach leverages a priori knowledge of molecular subtypes to transform complex gene expression data into a continuous feature space of lower dimensionality [28]. In contrast, MOA modeling restricts gene selection to those involved in the presumed biological pathway of a drug, creating a focused signature grounded in known pharmacology [28]. This guide objectively compares the performance, experimental protocols, and applications of these two methodologies within the critical framework of cross-platform validation.

Methodological Foundations and Experimental Protocols

The derivation of predictive signatures for two-arm clinical trials, where patients are randomized to different treatment arms, relies on multivariate Cox proportional hazard models. These models express the statistical dependence of patient survival time on both gene expression and treatment arm assignment [28]. The core statistical framework is described by the equation: $$ \log \left(\frac{\lambda \left(t|z,\mathbf{x}\right)}{\lambda0(t)}\right)={\beta}T\ast z+{\beta}G\ast X+\beta{TG}\ast z\ast X $$ Here, ( \lambda \left(t|z,\mathbf{x}\right) ) is the hazard at time ( t ) for a patient with gene expression vector ( X ) and treatment indicator ( z ) (e.g., 0 for control, 1 for investigational drug). The coefficient ( \beta_{TG} ) is particularly crucial as it captures the interaction between treatment and gene expression, forming the basis for a predictive signature [28].

Subtype Correlation (subC) Workflow

The subC methodology is built upon the established paradigm of intrinsic molecular subtypes in cancer [29] [28]. The workflow involves:

- Molecular Subtyping: Tumors are first classified into intrinsic subtypes (e.g., Luminal A, Luminal B, HER2-enriched, Basal-like) using a standardized method such as the PAM50 assay or a similar classifier [29] [28]. These subtypes serve as a major biological framework, each associated with specific clinical behaviors and therapeutic responses [29].

- Feature Space Transformation: Instead of using raw gene expression values, the expression profile of a new tumor is transformed into a continuous "subtype correlation" feature space. This is typically achieved by calculating the correlation between the tumor's expression profile and the prototypical expression profiles of each intrinsic subtype.

- Signature Derivation: These continuous correlation values, which represent the similarity of a tumor to each molecular subtype, are used as the input features for the multivariate Cox model to derive the final predictive signature [28].

Mechanism-of-Action (MOA) Workflow

The MOA modeling approach takes a more targeted path by incorporating prior biological knowledge:

- Gene Space Restriction: The initial pool of genes for analysis is restricted to those involved in the presumed mechanism of action of the drug under investigation. For example, when analyzing a drug like iniparib, an inducer of oxidative stress, the gene set would be limited to those involved in oxidative stress response pathways [28].

- Signature Derivation: This refined, biologically focused gene set is then used as input for the multivariate Cox model. This forces the resulting signature to be directly informed by the pharmacological target of the therapy, potentially enhancing its biological interpretability [28].

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflows and key differences between these two approaches.

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

The performance of subC and MOA modeling has been empirically tested in specific cancer indications, demonstrating their utility in patient stratification.

Quantitative Performance in Clinical Cohorts

Table 1: Comparative Performance of subC and MOA Modeling in Clinical Trials

| Cancer Indication | Modeling Approach | Therapy Context | Performance Outcome | Reference Cohort |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metastatic Colorectal Cancer (CRC) | subC | Aflibercept + FOLFIRI vs. FOLFIRI alone | Signature stratified patients into "sensitive" and "relatively-resistant" groups with a >2-fold difference in hazard ratios between groups. [28] | AFLAME trial (n=209) [28] |

| Triple-Negative Breast Cancer (TNBC) | MOA | Iniparib (induces oxidative stress) | Gene signature enabled stratification of patients with quantifiably different progression-free survival. [28] | Two-arm clinical trial (Specific cohort size not provided) [28] |

In the CRC use case, the subC approach successfully identified a patient population that derived significant benefit from the anti-angiogenic agent aflibercept. The resulting signature demonstrated a high probability of generalizability to similar CRC datasets upon cross-validation and resampling [28].

Cross-Platform Validation and Technical Considerations

A critical step in the development of any gene signature is its validation across different measurement platforms (e.g., microarrays, RNA-seq, qRT-PCR). Research shows that with careful probe mapping, gene expression signatures can maintain predictive power across platforms. One study demonstrated that by mapping probes between Affymetrix and Illumina microarrays as "mutual best matches" (probes targeting genomic regions <1000 base pairs apart), the resulting signatures used highly similar sets of genes and generated strongly correlated predictions of pathway activation [18].

Furthermore, the transition from microarray to RNA-seq data is feasible. Tools like the voom function can transform RNA-seq count data into continuous values that approximate a normal distribution, allowing statistical methods developed for microarrays to be applied directly. This facilitates the testing of a signature trained on one platform (e.g., microarray) on data generated from another (e.g., RNA-seq) [30].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Signature Development and Validation

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Signature Workflow | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| NanoString nCounter [29] [19] | Multiplexed digital quantification of mRNA transcripts without amplification; works with FFPE RNA. | Validation of a 42-gene neuroblastoma signature from microarray data in FFPE samples. [19] |

| PAM50 Classifier [29] | Standardized 50-gene set for intrinsic subtype classification of breast cancer. | Foundational classifier for defining subtypes in the subC approach. [29] [28] |

| Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA) [13] | R package for constructing co-expression networks and identifying modules of highly correlated genes. | Identification of gene modules correlated with survival and staging in lung adenocarcinoma. [13] |

| Frozen Robust Multiarray Analysis (fRMA) [30] | Algorithm for normalizing microarray data, allowing for the normalization of individual arrays against a frozen reference. | Pre-processing of multiple microarray datasets for meta-analysis to identify prognostic gene signatures. [30] |

| ComBat (Batch Correction) [28] | Algorithm for adjusting for batch effects in gene expression data, which is crucial when combining datasets. | Removal of batch effects in RNA-seq data from a clinical trial prior to signature construction. [28] |

Both subC and MOA modeling provide robust, data-driven frameworks for developing predictive gene signatures that can guide therapeutic decisions. The subC approach leverages the broad, unsupervised classification of intrinsic subtypes, making it particularly powerful when a well-established molecular taxonomy exists for the cancer type. The MOA approach offers high biological interpretability by tethering the signature directly to a drug's known pharmacological pathway. The choice between them may depend on the available biological knowledge and the clinical question at hand. Ultimately, the translational utility of any signature is contingent upon its rigorous validation, not just in independent cohorts, but also across the diverse technological platforms used in modern molecular pathology, a challenge that can be met with the reagents and methods detailed herein.

Multi-gene signature assays have revolutionized precision oncology by providing molecular insights that complement traditional clinicopathological factors for cancer prognosis and treatment prediction [31]. These assays analyze the expression levels of multiple genes simultaneously to generate a molecular portrait of tumors, enabling more refined prognostic and predictive information [29] [31]. However, the transition from research discoveries to clinically applicable tests requires rigorous validation across diverse datasets and technology platforms—a process heavily dependent on standardized computational workflows from data pre-processing to model training.