Digital PCR vs. qPCR for ctDNA Detection: A Guide to Precision, Sensitivity, and Clinical Application

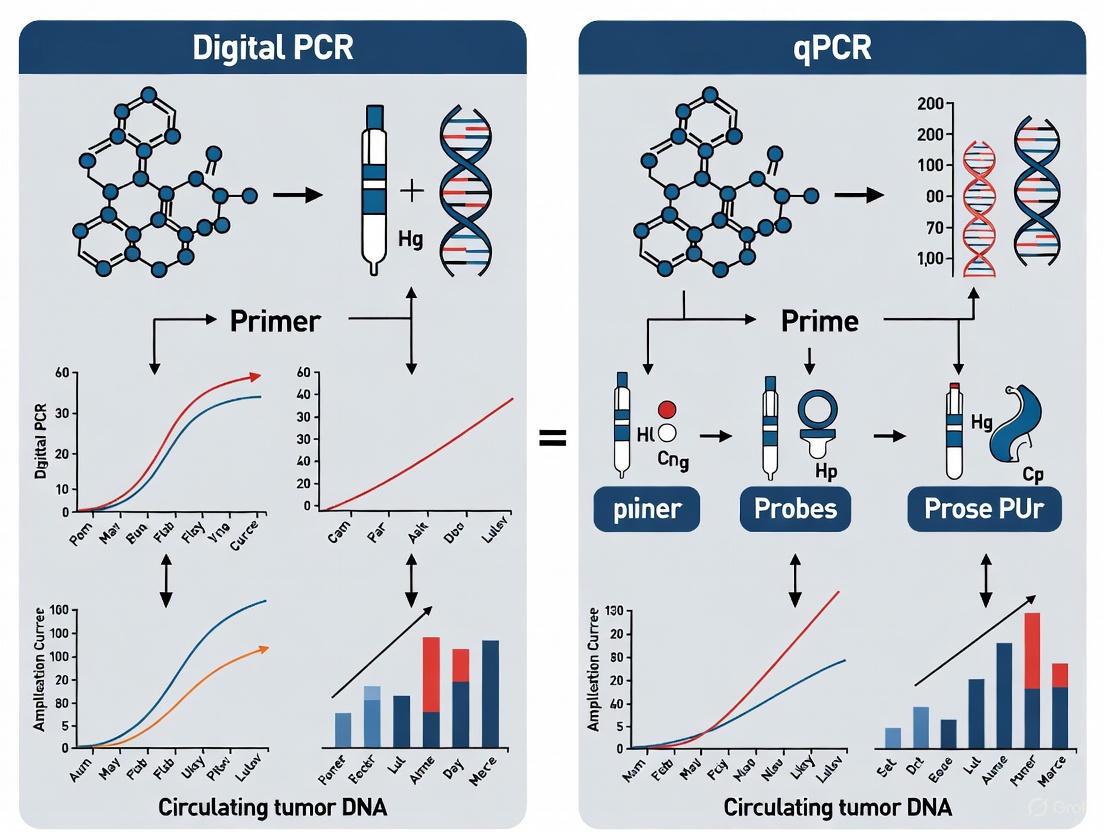

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of Digital PCR (dPCR) and Real-Time PCR (qPCR) for the detection and analysis of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA), a critical biomarker in liquid biopsies.

Digital PCR vs. qPCR for ctDNA Detection: A Guide to Precision, Sensitivity, and Clinical Application

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of Digital PCR (dPCR) and Real-Time PCR (qPCR) for the detection and analysis of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA), a critical biomarker in liquid biopsies. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers foundational principles, methodological workflows, and direct performance comparisons from recent studies. The content explores key applications in treatment monitoring and minimal residual disease (MRD) detection, offers practical troubleshooting advice, and synthesizes validation data to guide technology selection for specific research and clinical objectives in precision oncology.

Understanding ctDNA and PCR Technologies: Core Principles for Liquid Biopsies

Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) refers to small fragments of tumor-derived DNA found in the bloodstream, released through apoptosis or necrosis of cancer cells [1]. These fragments carry tumor-specific characteristics, including somatic mutations, making them valuable, minimally invasive biomarkers for cancer detection, monitoring, and treatment selection [1] [2]. In precision oncology, the analysis of ctDNA via liquid biopsy provides a dynamic snapshot of tumor burden and heterogeneity, enabling real-time monitoring of treatment response and disease progression [1] [3].

The detection and accurate quantification of ctDNA present significant technical challenges due to its low abundance in plasma, especially in early-stage disease, where it can constitute less than 0.1% of total cell-free DNA [4] [1]. This has driven the development of highly sensitive molecular techniques, primarily quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) and digital PCR (dPCR), each with distinct advantages for ctDNA analysis [5] [2]. While qPCR is a well-established, high-throughput method for relative quantification, dPCR offers absolute quantification without the need for standard curves, providing superior sensitivity and precision for detecting low-frequency mutations [6] [5]. This application note details experimental protocols and provides a comparative analysis of these two pivotal technologies in ctDNA research.

Comparative Performance of dPCR and qPCR for ctDNA Analysis

The choice between dPCR and qPCR is critical and depends on the specific application requirements. The table below summarizes their key characteristics relevant to ctDNA detection.

Table 1: Key Technical Comparisons between dPCR and qPCR for ctDNA Analysis

| Parameter | Digital PCR (dPCR) | Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qPCR) |

|---|---|---|

| Principle of Quantification | Absolute, based on direct counting of target molecules [5] | Relative, requires a standard curve [5] |

| Sensitivity for Rare Targets | Excellent; partitions and enriches low-abundance targets [5] | Limited; difficult to detect rare mutations in a high background [5] |

| Precision | High precision, particularly at low concentrations [6] [5] | Good precision, but lower than dPCR for low-abundance targets [6] |

| Dynamic Range | Narrower [5] | Wide (6-7 orders of magnitude) [5] |

| Tolerance to PCR Inhibitors | High; partitioning minimizes inhibitor effects [5] | Sensitive; inhibitors can reduce amplification efficiency [5] |

| Throughput | Lower | High (96- or 384-well formats) [5] |

| Cost Per Reaction | Higher [5] | Lower [5] |

| Ideal ctDNA Application | Detection of low-frequency mutations (<0.5% VAF), MRD, low-shedding tumors [4] [5] | High-throughput screening, monitoring high VAF mutations, gene expression [5] |

The superior sensitivity of dPCR is particularly valuable for detecting minimal residual disease (MRD) and mutations at low variant allele frequencies (VAF). A multi-site evaluation of ctDNA assays found that while mutations above 0.5% VAF were detected with high sensitivity by all leading assays, performance below this limit became unreliable and varied widely, with false negatives being a common challenge [4]. Furthermore, a meta-analysis on circulating tumor HPV DNA (ctHPVDNA) demonstrated that detection sensitivity was greatest with NGS, followed by dPCR (ddPCR), and then qPCR, highlighting dPCR's intermediate position in the sensitivity hierarchy [7].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Blood Collection and Plasma Processing for ctDNA Analysis

Principle: To obtain high-quality, cell-free plasma with maximal yield and integrity of ctDNA, minimizing contamination from genomic DNA of blood cells [8].

Workflow Diagram: Plasma and ctDNA Isolation

Materials & Reagents:

- Blood Collection Tubes: Cell-free DNA BCT tubes (Streck), K2EDTA or K3EDTA tubes [3].

- Centrifuges: Swing-bucket centrifuge capable of 2,000 x g and high-speed microcentrifuge capable of 16,000 x g.

- Pipettes and Sterile Tips.

- Polypropylene Tubes: Low DNA binding, sterile.

- DNA Extraction Kit: QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (Qiagen) or QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid Kit (Qiagen) [6] [3].

- Quantification Instrument: Fluorometer (e.g., Qubit, Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Procedure:

- Blood Draw: Collect venous blood into approved cell-free DNA blood collection tubes. Invert gently 8-10 times. Process within 1-4 hours if using EDTA tubes; specialized BCT tubes can stabilize blood for several days at room temperature.

- First Centrifugation: Centrifuge blood tubes at 1,600-2,000 x g for 10 minutes at 4°C to separate plasma from blood cells.

- Plasma Transfer: Carefully transfer the upper plasma layer to a new microcentrifuge tube using a sterile pipette, avoiding the buffy coat (white cell layer).

- Second Centrifugation: Centrifuge the transferred plasma at 16,000 x g for 10 minutes at 4°C to remove any remaining cellular debris.

- Cleared Plasma Transfer: Transfer the supernatant (cleared plasma) to a new, labeled microcentrifuge tube. Plasma can be stored at -80°C or used immediately for DNA extraction.

- cfDNA Extraction: Extract cfDNA from plasma (typically 1-5 mL) using a commercial kit (e.g., QIAamp DNA Mini kit) according to the manufacturer's instructions [6]. Elute DNA in a small volume (e.g., 20-50 µL) of nuclease-free water or the provided elution buffer.

- Quantification and QC: Quantify the extracted cfDNA using a fluorescence-based method (e.g., Qubit dsDNA HS Assay). Assess DNA fragment size distribution using a Bioanalyzer or TapeStation if available.

Protocol: Detection of a Point Mutation via dPCR

Principle: The sample is partitioned into thousands of nanoliter-scale reactions. Following endpoint PCR amplification, each partition is analyzed for fluorescence to absolutely quantify the mutant and wild-type alleles based on Poisson statistics [5].

Workflow Diagram: dPCR Mutation Detection

Materials & Reagents:

- dPCR System: QIAcuity (Qiagen), Bio-Rad QX200 Droplet Digital PCR, or similar.

- dPCR Supermix: QIAcuity Probe PCR Kit (Qiagen) or ddPCR Supermix for Probes (Bio-Rad) [6].

- Primers and Probes: Validated, specific primers and double-quenched hydrolysis probes (e.g., FAM-labeled for mutant allele, HEX/VIC-labeled for wild-type allele) [6].

- Restriction Enzyme: PvuII or similar (optional, to reduce background) [6].

- Nuclease-Free Water.

- Plate or Cartridge: As required by the dPCR instrument (e.g., QIAcuity Nanoplate 26k).

Procedure:

- Reaction Setup: Prepare a 40 µL dPCR reaction mix on ice containing:

- 1x dPCR Supermix

- 900 nM of each primer (final concentration)

- 250 nM of each probe (final concentration)

- 10 µL of extracted cfDNA template

- 0.025 U/µL restriction enzyme (if using)

- Nuclease-free water to volume

- Partitioning: Load the reaction mixture into the dPCR plate or cartridge and perform partitioning according to the manufacturer's protocol (e.g., generating ~20,000 droplets for ddPCR or ~26,000 partitions for the QIAcuity nanoplate system) [6].

- PCR Amplification: Run the PCR with the following optimized cycling conditions:

- Enzyme Activation: 95°C for 2 minutes

- 45 Cycles of:

- Denaturation: 95°C for 15 seconds

- Annealing/Extension: 58-60°C for 1 minute

- Hold: 4°C or 98°C (for seal integrity)

- Fluorescence Reading: After amplification, place the plate/cartridge in the reader to measure the fluorescence in each partition.

- Data Analysis: Use the instrument's software (e.g., QIAcuity Software Suite) to set thresholds and classify partitions as mutant-positive, wild-type-positive, double-positive, or negative. The software will automatically apply Poisson statistics to calculate the absolute concentration (copies/µL) of the mutant and wild-type alleles in the original sample [6]. Calculate the variant allele frequency (VAF) as [Mutant concentration / (Mutant + Wild-type concentration)].

Protocol: Relative Quantification of a Genetic Alteration via qPCR

Principle: Fluorescence accumulation is monitored during each PCR cycle. The cycle threshold (Ct) at which fluorescence crosses a defined threshold is inversely proportional to the starting quantity of the target, which is determined by comparison to a standard curve [5].

Materials & Reagents:

- qPCR Instrument: Any real-time PCR system (e.g., from Applied Biosystems, Bio-Rad, Roche).

- qPCR Master Mix: TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix or equivalent.

- Primers and Probes: As designed for the target mutation and a reference control gene.

- DNA Standards: Serial dilutions of synthetic oligonucleotides or plasmid DNA with known concentrations of the wild-type and mutant sequences.

- Microplate or Strips: 96-well or 384-well optical reaction plates.

Procedure:

- Standard Curve Preparation: Prepare a 5- to 10-fold serial dilution of the standard DNA, spanning the expected concentration range of the target in the samples (e.g., from 10^6 to 10^1 copies/µL).

- Reaction Setup: Prepare a 20 µL qPCR reaction mix per well containing:

- 1x TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix

- 900 nM of each primer

- 250 nM of probe

- 5 µL of cfDNA template (for samples) or standard

- Nuclease-free water to volume

- Amplification: Run the plate in the qPCR instrument with the following standard cycling conditions:

- Enzyme Activation: 50°C for 2 minutes (UDG incubation, if used) and 95°C for 10 minutes

- 40-45 Cycles of:

- Denaturation: 95°C for 15 seconds

- Annealing/Extension: 60°C for 1 minute

- Data Analysis:

- The instrument's software will generate amplification plots and assign Ct values to each reaction.

- Generate a standard curve by plotting the Ct values of the standards against the logarithm of their known concentrations. The efficiency (E) of the PCR can be calculated from the slope of the standard curve: E = 10^(-1/slope) - 1.

- Use the standard curve equation to interpolate the starting quantity of the target in each unknown sample. Results are often reported as relative quantities after normalization to a reference gene.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Kits for ctDNA Detection via dPCR/qPCR

| Reagent/Kits | Primary Function | Example Products & Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Cell-free DNA Blood Collection Tubes | Stabilize blood cells and prevent genomic DNA contamination for up to 14 days. | Streck Cell-Free DNA BCT Tubes, PAXgene Blood cDNA Tubes [3]. |

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits | Isolate and purify cfDNA from plasma or serum. | QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (Qiagen), QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid Kit (Qiagen) [6] [3]. |

| dPCR Master Mixes | Provide optimized buffers, nucleotides, and enzyme for partitioned PCR. | QIAcuity Probe PCR Kit (Qiagen), ddPCR Supermix for Probes (Bio-Rad) [6]. |

| qPCR Master Mixes | Provide optimized components for real-time fluorescent PCR. | TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix (Thermo Fisher). |

| Assay Design Tools | In silico design and validation of primers and probes. | Primer-BLAST (NCBI), Bio-Rad ddPCR Assay Design Tool. |

| Validated Assays | Pre-designed and tested assays for common oncogenic mutations. | Bio-Rad ddPCR Mutation Assays, Thermo Fisher TaqMan Mutation Assays. |

| Fluorometers & Analyzers | Accurately quantify and qualify low-concentration, fragmented DNA. | Qubit Fluorometer (Thermo Fisher), Agilent Bioanalyzer. |

| Synthetic DNA Standards | Serve as positive controls and for generating standard curves in qPCR. | gBlocks Gene Fragments (IDT), custom synthetic oligonucleotides. |

The integration of ctDNA analysis into precision oncology represents a significant advancement in cancer management. Both dPCR and qPCR are powerful tools for ctDNA detection, yet they serve complementary roles. dPCR, with its absolute quantification, superior sensitivity for low-frequency mutations, and robustness to inhibitors, is ideally suited for applications like MRD detection and validating mutations identified by NGS [6] [5]. In contrast, qPCR remains a cost-effective and high-throughput solution for screening known mutations present at higher VAFs or for gene expression studies [5]. The ongoing refinement of these protocols and technologies will continue to enhance the sensitivity and reproducibility of ctDNA measurements, further solidifying its role as a dynamic biomarker in clinical research and therapeutic decision-making.

The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) has undergone a transformative evolution since its inception, moving from qualitative endpoint detection to sophisticated quantitative methodologies. Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) emerged as a revolutionary technology that enabled researchers to monitor amplification as it occurred, providing relative quantification of nucleic acid targets across a wide dynamic range. This technique became the workhorse of molecular biology laboratories, supporting applications from gene expression analysis to pathogen detection. However, its reliance on calibration curves and its susceptibility to amplification inefficiencies revealed inherent limitations, particularly for applications requiring absolute quantification or detection of rare targets [9].

The development of digital PCR (dPCR) represents the latest paradigm shift in nucleic acid quantification. By combining limiting dilution, endpoint PCR, and Poisson statistics, dPCR enables absolute quantification of target molecules without requiring standard curves [10]. This technical advancement has proven particularly valuable for detecting minor genetic variants against a background of wild-type sequences—a common challenge in circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) detection where tumor-derived DNA fragments may represent less than 0.1% of total cell-free DNA [10]. As molecular diagnostics continues to advance toward more precise quantification, understanding the technological evolution from qPCR to dPCR becomes essential for researchers designing next-generation liquid biopsy assays.

Technical Principles: Fundamental Differences Between qPCR and dPCR

qPCR: Relative Quantification Based on Amplification Kinetics

In qPCR, the accumulation of PCR product is monitored in real-time through fluorescent chemistry, with the quantification cycle (Cq) representing the cycle number at which fluorescence exceeds a detection threshold. Target concentration is determined by comparing the Cq values of unknown samples to those of a standard curve with known concentrations [9]. This approach provides relative quantification across a linear dynamic range typically spanning 5-6 orders of magnitude. The technique relies on the assumption that amplification efficiency remains constant between samples and standards, which can be compromised by PCR inhibitors or suboptimal reaction conditions [11].

The MIQE guidelines were established to standardize qPCR experiments and publications, emphasizing the need for detailed reporting of experimental conditions, including nucleic acid extraction methods, target information, amplification efficiency, and normalization strategies [12]. Despite these guidelines, compliance remains inconsistent, leading to concerns about reproducibility in the literature. Common limitations include inadequate validation of reference genes, unreported PCR efficiency calculations, and inappropriate statistical justification [12].

dPCR: Absolute Quantification Through Sample Partitioning

Digital PCR takes a fundamentally different approach by dividing a PCR reaction into thousands to millions of separate partitions, effectively creating a matrix of individual PCR reactions. After endpoint amplification, each partition is analyzed as positive or negative for target amplification, with the ratio of positive to total partitions enabling absolute quantification of the target molecule based on Poisson statistics [13] [10].

This partitioning approach provides several distinctive advantages. First, it eliminates the dependency on external standards and amplification efficiency, as quantification depends solely on binary endpoint detection. Second, it significantly enhances resistance to PCR inhibitors, as the effect is diluted across partitions rather than affecting the bulk reaction. Third, it dramatically improves precision and sensitivity for rare allele detection, enabling identification of mutant alleles present at frequencies as low as 0.001% in a background of wild-type sequences [10].

Table 1: Core Technical Differences Between qPCR and dPCR

| Parameter | qPCR | dPCR |

|---|---|---|

| Quantification Type | Relative (requires standard curve) | Absolute (no standard curve needed) |

| Detection Principle | Real-time fluorescence monitoring | Endpoint binary detection (positive/negative partitions) |

| Dynamic Range | 5-6 logs | 4-5 logs |

| Precision | Distinguishes ~1.5-fold changes | Distinguishes ~1.2-fold changes |

| Susceptibility to Inhibitors | Moderate to high | Low |

| Multiplexing Capability | High (with spectral resolution) | Moderate (limited by partition number) |

| Throughput | High | Moderate |

| Cost per Sample | Low | High |

Comparative Performance: Analytical Validation Across Applications

Sensitivity and Precision

Multiple studies have demonstrated the superior sensitivity and precision of dPCR, particularly at target concentrations where qPCR begins to lose linearity. In viral load testing, dPCR has shown less variability at higher concentrations for WHO international standards compared to qPCR [11]. A 2025 study comparing respiratory virus detection reported that dPCR demonstrated "superior accuracy, particularly for high viral loads of influenza A, influenza B, and SARS-CoV-2, and for medium loads of RSV" with "greater consistency and precision than Real-Time RT-PCR" [14].

The enhanced precision of dPCR enables more reliable detection of small-fold changes, with studies reporting the ability to distinguish 1.2-fold differences in target concentration compared to 1.5-fold changes typically detectable by qPCR [10]. This heightened sensitivity is particularly valuable in ctDNA monitoring, where small changes in mutant allele frequency may indicate early treatment response or emerging resistance.

Limits of Detection and Quantification

The limit of detection (LOD) and limit of quantification (LOQ) represent critical performance parameters for ctDNA analysis. In a comparative study of dPCR platforms, the LOD for nanoplate-based dPCR was approximately 0.39 copies/μL input, while droplet-based dPCR showed an LOD of 0.17 copies/μL input [13]. The LOQ was determined to be 1.35 copies/μL input for the nanoplate system and 4.26 copies/μL input for the droplet system [13].

For SARS-CoV-2 detection, studies have demonstrated that dPCR provides enhanced sensitivity compared to qPCR, particularly in samples with low viral load where it detected additional positive cases missed by qPCR [15]. This improved detection capability directly translates to ctDNA applications, where tumor-derived DNA fragments often exist at extremely low concentrations amidst abundant wild-type DNA.

Table 2: Performance Comparison Across PCR Platforms in Recent Studies

| Study | Target | qPCR Performance | dPCR Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Suo et al. 2022 [15] | SARS-CoV-2 | 89/130 positive samples | 93/130 positive samples |

| Zhang et al. 2025 [14] | Respiratory viruses | Variable quantification across viral load ranges | Superior accuracy for high viral loads |

| Platform Comparison 2025 [13] | Synthetic oligonucleotides | Not tested | R²adj = 0.98-0.99, CV: 6-13% |

| Hayden et al. 2013 [11] | Cytomegalovirus | LOD: 3 log₁₀ copies/mL | LOD: 4 log₁₀ copies/mL |

Application to ctDNA Detection: Technical Considerations and Protocols

Sample Preparation and Pre-Analytical Variables

For ctDNA analysis, proper sample handling is critical. Blood collection should utilize specialized tubes that stabilize nucleated blood cells and prevent genomic DNA contamination. Plasma separation should occur within 2-6 hours of collection, followed by double centrifugation to remove residual cells. DNA extraction should employ optimized kits specifically designed for low-abundance cell-free DNA, with careful attention to elution volume to maximize concentration [14] [15].

The quality and integrity of extracted nucleic acids should be thoroughly assessed using appropriate methods. The MIQE 2.0 guidelines emphasize that "nucleic acid quality and integrity are not properly assessed" in many studies, representing a fundamental methodological failure that can compromise ctDNA detection [12].

dPCR Assay Design and Optimization for Rare Allele Detection

Effective ctDNA detection requires careful assay design to maximize specificity and sensitivity. Assays should be designed with short amplicon lengths (60-100 bp) to accommodate the fragmented nature of cell-free DNA. Probes should be positioned to cover the mutation of interest, with stringent bioinformatic analysis to ensure specificity.

Restriction enzyme selection can significantly impact assay performance, especially for targets with potential tandem repeats. A 2025 study demonstrated that "CVs were higher for ddPCR compared to ndPCR for all cell numbers except 100 cells for the assay using EcoRI," while "using HaeIII as a restriction enzyme, the overall precision was increased for ddPCR with all CVs lower than 5%" [13]. This highlights the importance of enzyme selection during assay optimization.

Detailed dPCR Protocol for ctDNA Detection

Protocol: Rare Mutation Detection in Cell-Free DNA Using dPCR

Reagents and Equipment:

- QIAcuity One digital PCR system (QIAGEN) or QX200 Droplet Digital PCR System (Bio-Rad)

- dPCR Master Mix (probe-based)

- Mutation-specific FAM-labeled probe and wild-type HEX-labeled probe

- Restriction enzyme (HaeIII or alternative optimized for target)

- Nuclease-free water

- PCR plates or cartridges compatible with platform

Procedure:

- Reaction Mixture Preparation:

- Prepare master mix containing 11 μL dPCR supermix, 1.1 μL of each primer (900 nM final concentration), 0.5 μL of each probe (250 nM final concentration), 1 U restriction enzyme, and 5 μL template DNA in a total volume of 20-25 μL depending on platform specifications.

- Include negative controls (nuclease-free water) and positive controls (synthetic oligonucleotides with known mutation frequency).

Partitioning:

- For nanoplate systems: Load entire reaction volume into appropriate well(s).

- For droplet systems: Generate droplets according to manufacturer's protocol using droplet generation oil and cartridges.

PCR Amplification:

- Perform endpoint PCR with the following cycling conditions:

- Enzyme activation: 95°C for 10 minutes

- 40-45 cycles of:

- Denaturation: 95°C for 30 seconds

- Annealing/Extension: 55-60°C for 60 seconds

- Enzyme deactivation: 98°C for 10 minutes

- Hold: 4-12°C

- Perform endpoint PCR with the following cycling conditions:

Signal Detection and Analysis:

- For nanoplate systems: Image each well using integrated imaging system.

- For droplet systems: Read droplets using droplet reader.

- Analyze using manufacturer's software with appropriate threshold settings.

- Apply Poisson correction to calculate absolute copy numbers.

Data Interpretation:

- Calculate mutant allele frequency as (mutant copies / total copies) × 100.

- Report confidence intervals based on Poisson statistics.

- For longitudinal monitoring, calculate fold-change relative to baseline.

Research Reagent Solutions for ctDNA Analysis

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Kits for dPCR-based ctDNA Detection

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in ctDNA Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Blood Collection Tubes | Cell-Free DNA Blood Collection Tubes (Roche, Streck) | Preserves blood sample integrity and prevents background DNA release |

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits | MagMax Viral/Pathogen Kit, QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid Kit | Isolates low-abundance cell-free DNA with high efficiency and reproducibility |

| dPCR Master Mixes | ddPCR Supermix for Probes (Bio-Rad), QIAcuity PCR Master Mix (QIAGEN) | Provides optimized reaction components for partition-based amplification |

| Mutation Detection Assays | Custom TaqMan SNP Genotyping Assays, PrimePCR dPCR Mutation Assays | Enables specific detection of tumor-specific mutations against wild-type background |

| Reference Assays | Copy Number Reference Assays, Reference Gene Assays | Normalizes for technical variation in DNA input and partitioning efficiency |

| Quantification Standards | Synthetic Oligonucleotides, gBlocks Gene Fragments | Validates assay performance and establishes limits of detection |

Implementation Workflows and Data Analysis

Experimental Workflow for ctDNA Analysis

The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow for ctDNA analysis using dPCR, highlighting critical decision points from sample collection through data interpretation:

Data Analysis Framework

Proper data analysis is essential for accurate ctDNA quantification. The application of Poisson statistics corrects for the probability of multiple target molecules occupying a single partition. Quality thresholds should be established to exclude partitions with ambiguous signals, and replicate testing should be implemented for clinical applications.

For longitudinal monitoring, statistical significance should be established based on the confidence intervals provided by dPCR analysis rather than simple fold-change calculations. The MIQE 2.0 guidelines emphasize that "fold-changes of 1.2- or 1.5-fold are routinely reported as biologically meaningful, even at low expression levels, without any assessment of measurement uncertainty or technical variance" [12], highlighting the importance of appropriate statistical treatment.

The evolution from qPCR to dPCR represents a significant advancement in nucleic acid quantification technology, with particular relevance for ctDNA detection in oncology. While qPCR remains a cost-effective solution for high-throughput applications with moderate sensitivity requirements, dPCR offers distinct advantages for absolute quantification, rare allele detection, and analysis of samples with potential inhibitors.

The higher cost and lower throughput of dPCR currently limit its implementation in routine screening, but its superior precision and sensitivity make it ideally suited for monitoring minimal residual disease and treatment response in cancer patients [9] [14]. As the technology continues to evolve with increased automation and reduced costs, dPCR is poised to become an increasingly essential tool in the liquid biopsy arsenal, potentially enabling earlier cancer detection and more personalized treatment approaches.

For researchers implementing dPCR for ctDNA applications, adherence to the dMIQE guidelines ensures methodological rigor, while careful attention to pre-analytical variables and assay optimization maximizes the technology's considerable potential for transforming cancer diagnostics and monitoring.

Quantitative PCR (qPCR), also known as real-time PCR, represents a fundamental advancement in molecular biology by enabling precise quantification of nucleic acids throughout the amplification process rather than just at the end. This technique relies on detecting fluorescent signals that increase proportionally to the amount of PCR product generated in each cycle. For research on circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA)—where detecting minute genetic changes in a complex background is critical—qPCR offers a balance of sensitivity, throughput, and accessibility.

The fluorescence detection system in qPCR consists of four essential components: (1) an excitation light source, (2) a fluorescent reporter dye, (3) wavelength-specific filters to separate emission photons from excitation photons, and (4) a detector that records the emission signal [16]. This configuration takes advantage of the fundamental fluorescence process where light energy at a specific wavelength is absorbed by a fluorophore, creating an excited electronic state, followed by emission of light at a longer wavelength as the fluorophore returns to its ground state. The difference between excitation and emission wavelengths, known as the Stokes shift, is crucial for sensitive detection as it enables separation of the signal from background noise [16].

In ctDNA research, this sensitive detection capability allows researchers to identify and quantify specific tumor-derived mutations present at low frequencies in patient blood samples, providing a non-invasive method for monitoring cancer progression and treatment response.

Principles of Fluorescence Detection in qPCR

Fluorescence Chemistry and Detection Systems

The core principle of qPCR detection relies on measuring fluorescence intensity that correlates directly with accumulated PCR product. Two primary fluorescence detection chemistries are employed in qPCR:

DNA-Binding Dyes: SYBR Green is the most common example, which fluoresces brightly when bound to double-stranded DNA. As PCR product accumulates with each cycle, more dye molecules bind and the fluorescent signal increases proportionally. While cost-effective and flexible, these dyes bind non-specifically to any double-stranded DNA, including primer-dimers, potentially leading to overestimated target concentration.

Sequence-Specific Probes: The 5' nuclease assay (TaqMan) uses dual-labeled probes containing a 5' fluorophore and a 3' quencher. When intact, the proximity of quencher to fluorophore prevents fluorescence detection through fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET). During PCR amplification, the DNA polymerase's 5'→3' exonuclease activity cleaves the probe, separating the fluorophore from the quencher and generating a fluorescent signal [17]. This mechanism ensures that fluorescence increase specifically indicates amplification of the target sequence, making it particularly valuable for detecting specific mutations in ctDNA analysis.

Instrumentation and Signal Processing

qPCR instruments must precisely control temperature cycling while simultaneously exciting fluorophores and detecting emission signals across multiple wavelengths. Modern instruments typically include several detection channels, allowing simultaneous measurement of different fluorophores in multiplex reactions—a critical capability for detecting multiple mutations or normalizing to reference genes in ctDNA studies.

Proper signal processing requires careful setup of two key parameters that significantly impact data quality and quantification accuracy. The baseline fluorescence represents background signal during initial PCR cycles before detectable product accumulation, while the threshold is set within the exponential phase where reaction efficiency is optimal [18]. The cycle at which each sample's amplification curve crosses this threshold (Cq or Ct value) forms the basis for quantification.

Table 1: Critical Fluorescence Detection Parameters in qPCR

| Parameter | Definition | Optimal Setup | Impact on Quantification |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Background fluorescence during initial cycles | Set from cycles where fluorescence is stable but above background | Incorrect setting distorts Cq values and curve shape |

| Threshold | Fluorescence level above background in exponential phase | Set within parallel, logarithmic phase of all amplifications | Affects absolute Cq but not ΔCq if amplifications are parallel |

| Cq (Quantification Cycle) | Cycle number at which fluorescence crosses threshold | Automatically or manually determined after baseline/threshold setup | Lower Cq indicates higher initial template concentration |

Relative Quantification Strategies in qPCR

Fundamentals of Relative Quantification

Relative quantification determines changes in gene expression by comparing the amount of target gene between test and reference samples, with normalization to one or more stably expressed reference genes. Unlike absolute quantification—which calculates exact copy numbers using a standard curve—relative quantification expresses results as fold-differences, making it particularly suitable for studying expression changes in response to experimental conditions or disease states [19].

In ctDNA research, relative quantification can be employed to assess ratio changes between mutant and wild-type alleles or to normalize ctDNA levels to reference genes, though absolute quantification is often preferred for precise mutation load assessment. The relative quantification framework consists of several key components:

- Target Gene: The sequence of interest (e.g., a tumor-specific mutation)

- Reference Gene(s): Stably expressed endogenous controls used for normalization (e.g., ACTB, GAPDH, HPRT)

- Calibrator Sample: A reference point for comparison (e.g., a control sample or pre-treatment time point)

- Experimental Samples: Test specimens compared against the calibrator

Mathematical Models for Relative Quantification

Two primary mathematical approaches dominate relative quantification in qPCR, each with specific applications and requirements.

Comparative Cq (ΔΔCq) Method: This approach assumes that amplification efficiencies of target and reference genes are approximately equal and close to 100% (meaning the PCR product doubles each cycle) [20]. The method involves:

- Calculating ΔCq for each sample: Cq(target) - Cq(reference)

- Calculating ΔΔCq: ΔCq(test sample) - ΔCq(calibrator sample)

- Determining fold-change: 2^(-ΔΔCq)

This method's simplicity makes it widely popular, but its accuracy depends heavily on the efficiency assumption [21]. Efficiency can be verified by ensuring the absolute value of the slope of ΔCq plotted against log input cDNA dilution is less than 0.1 [22].

Pfaffl (Efficiency-Corrected) Method: When amplification efficiencies of target and reference genes differ significantly (typically >5%), the Pfaffl method incorporates actual efficiency values into the calculation [20]:

[ \text{Fold Change} = \frac{(E{\text{target}})^{\Delta Cq{\text{target}}}}{(E{\text{reference}})^{\Delta Cq{\text{reference}}}} ]

Where E represents the amplification efficiency (1.0-2.0) calculated from standard curves, and ΔCq represents the difference in Cq values between calibrator and test samples for each gene [21]. This method provides more accurate results when efficiency differences exist but requires additional validation experiments.

Table 2: Comparison of Relative Quantification Methods

| Characteristic | Comparative Cq (ΔΔCq) Method | Pfaffl (Efficiency-Corrected) Method |

|---|---|---|

| Efficiency Assumption | Equal, near-perfect efficiencies for target and reference genes | Accommodates different efficiencies between genes |

| Standard Curve Requirement | Not required | Required for efficiency determination |

| Calculation Complexity | Simple calculation | More complex, efficiency-dependent formula |

| Accuracy Conditions | High accuracy when efficiency assumption valid | Superior accuracy when efficiencies differ |

| Validation Requirement | Must demonstrate similar efficiencies | Must determine precise efficiency values |

| Throughput | Higher - no standard curve wells needed | Lower - requires standard curve on each plate |

Experimental Protocol for Relative Quantification

Assay Design and Validation

Primer and Probe Design: Effective qPCR begins with careful assay design. For 5' nuclease assays, primers should have Tm values of approximately 60-62°C, length of 18-30 bases, and GC content of 35-65% without runs of more than 4 consecutive G bases [17]. The probe should have a Tm 5-10°C higher than primers, be ≤30 bases for optimal quenching, and avoid G at the 5' end which can quench common fluorophores like FAM [17]. For gene expression studies, design primers to span exon-exon junctions to prevent genomic DNA amplification.

Amplification Efficiency Determination: Before relative quantification, determine amplification efficiency for each primer pair:

- Prepare a 5-point, 10-fold serial dilution of cDNA pool

- Run qPCR with all dilutions in duplicate

- Plot Cq values against log template dilution

- Calculate slope and efficiency: E = 10^(-1/slope)

- Convert to percentage: % Efficiency = (E-1) × 100

Ideal reactions display efficiency of 90-110% (slope of -3.6 to -3.1) [20]. Efficiency outside this range typically requires primer redesign.

Experimental Setup and Controls

Reference Gene Selection: Reference genes must show stable expression across all experimental conditions. Validate candidate reference genes using algorithms like geNorm or NormFinder [20]. For ctDNA studies, select reference genes unaffected by the disease state or treatment.

Essential Experimental Controls:

- No-template controls (NTC): Identify contamination

- No-reverse-transcription controls (-RT): Detect genomic DNA contamination

- Inter-plate calibrators: Enable normalization across multiple runs

- Technical replicates: Minimum of three replicates per sample

qPCR Reaction Setup:

- Keep total reaction volume consistent across all wells

- Do not exceed 1/10 of total reaction volume with cDNA mixture

- Use validated master mix according to manufacturer's cycling conditions

- Include standard curve dilutions on each plate for efficiency-corrected methods

Application in Circulating Tumor DNA Research

qPCR for ctDNA Analysis

In ctDNA research, qPCR enables non-invasive "liquid biopsy" approaches for cancer monitoring, treatment selection, and recurrence detection. Specific applications include:

Mutation Detection: Target tumor-specific mutations (e.g., KRAS, EGFR, PIK3CA) using allele-specific qPCR assays. These assays typically use specialized primer/probe designs that preferentially amplify mutant alleles while suppressing wild-type amplification, enabling detection of mutant alleles at frequencies as low as 0.1-1% [23].

Expression Profiling: Quantify expression levels of cancer-associated genes (e.g., DNA methylation markers) in circulating nucleic acids. This requires careful normalization to reference genes that are stably expressed in blood and unaffected by the disease process.

Treatment Monitoring: Track mutation levels over time to assess therapeutic response. Decreasing mutant allele frequency typically indicates positive treatment response, while increasing levels may signal resistance or recurrence.

Comparison with Digital PCR for ctDNA Analysis

While qPCR provides a robust platform for ctDNA analysis, digital PCR (dPCR) offers complementary advantages for certain applications. dPCR partitions samples into thousands of individual reactions, enabling absolute quantification without standard curves and improved detection of rare variants [19]. Recent studies directly comparing these technologies found that droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) detected ctDNA in 58.5% of baseline plasma samples from rectal cancer patients compared to 36.6% with next-generation sequencing panels, demonstrating its high sensitivity for low-abundance targets [23].

For longitudinal monitoring, dPCR's precision enables detection of molecular recurrence months before clinical relapse, particularly valuable for monitoring minimal residual disease [24]. However, qPCR maintains advantages in throughput, multiplexing capability, and established workflows, making it suitable for screening applications or when absolute quantification is not required.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for qPCR Relative Quantification

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorescence Chemistries | SYBR Green, FAM/TAMRA probes, Molecular Beacons | Detect PCR product accumulation through fluorescence emission |

| Reverse Transcriptase | M-MLV, SuperScript IV | Convert RNA to cDNA for gene expression studies |

| qPCR Master Mix | TaqMan Fast Advanced, PowerUp SYBR Green | Provide optimized buffer, enzymes, dNTPs for efficient amplification |

| Reference Genes | ACTB, GAPDH, HPRT, 18S rRNA | Normalize for sample input variation in relative quantification |

| Nuclease-Free Water | Ambion Nuclease-Free Water | Prevent RNA/DNA degradation during reaction setup |

| Positive Controls | Synthetic DNA/RNA standards, Control plasmids | Verify assay performance and enable absolute quantification |

| Inhibition Relief Agents | BSA, T4 Gene 32 Protein | Counteract PCR inhibitors in complex biological samples |

Troubleshooting and Quality Control

Data Quality Assessment

Implement rigorous quality control measures to ensure reliable relative quantification results:

Amplification Curve Analysis: Check that all curves display characteristic sigmoidal shape with clear exponential phases. Irregular curves may indicate inhibition, poor primer design, or pipetting errors.

Amplification Efficiency: Confirm efficiencies between 90-110% for all assays. Significantly higher efficiencies may indicate primer-dimer formation, while lower efficiencies suggest inhibition or suboptimal reaction conditions.

Reference Gene Stability: Verify stable expression of reference genes across experimental conditions using algorithms like geNorm or NormFinder. Instability requires selection of alternative reference genes or use of multiple genes for normalization.

Reproducibility: Technical replicates should show minimal variation (Cq standard deviation < 0.5 cycles). Higher variation indicates technical issues with pipetting, mixing, or template quality.

Common Issues and Solutions

- High Background Fluorescence: Optimize probe concentration, ensure proper quenching, and check instrument calibration

- Poor Amplification Efficiency: Re-optimize primer concentrations, check for SNPs in binding sites, and verify template quality

- Inconsistent Replicates: Improve pipetting technique, ensure complete mixing of reactions, and check for evaporation

- Reference Gene Instability: Test additional reference genes and use geometric mean of multiple stable genes for normalization

Adherence to the MIQE (Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments) guidelines ensures experimental rigor and reproducibility by providing a comprehensive framework for reporting qPCR experiments [25].

Core Principle of Absolute Quantification

Digital PCR (dPCR), including its droplet-based format (ddPCR), enables the absolute quantification of nucleic acid targets without the need for a standard curve. This method relies on sample partitioning, end-point PCR, and Poisson statistical analysis to count individual DNA molecules [26].

The fundamental process involves dividing a PCR reaction into thousands of nano-sized partitions, effectively creating individual microreactors. After amplification, each partition is analyzed for fluorescence. Partitions containing the target sequence (positive) are counted against those without it (negative). The ratio of positive to total partitions allows for calculation of the absolute target concentration in the original sample using Poisson distribution statistics [26].

Table 1: Key Differences between qPCR and dPCR/ddPCR

| Feature | Quantitative PCR (qPCR) | Digital/Droplet Digital PCR (dPCR/ddPCR) |

|---|---|---|

| Quantification Basis | Relative to standard curve | Absolute counting of molecules |

| Calibration Requirement | Requires external standards & calibration curve | No standard curve needed |

| Signal Measurement | Real-time during exponential phase | End-point detection |

| Data Output | Cycle threshold (Ct) value | Number of positive and negative partitions |

| Statistical Foundation | Comparative Ct quantification | Poisson distribution |

| Tolerance to Inhibitors | Moderate | High [26] |

| Sensitivity for Rare Mutations | Limited | High due to partitioning [26] |

The Partitioning Process and Statistical Foundation

Partitioning and Poisson Distribution

The partitioning step is critical for the absolute quantification of dPCR. The sample is randomly distributed across many partitions, with each partition containing zero, one, or a few target molecules [26]. This random distribution follows a Poisson distribution, which is described by the equation:

P(k) = (e^(-λ) * λ^k) / k!

Where:

- P(k) = Probability that a partition contains k target molecules

- λ = Average number of target molecules per partition (the concentration to be determined)

- k = Actual number of target molecules in a specific partition

- e = Base of the natural logarithm (~2.71828) [26]

The probability (p) that a partition contains at least one target molecule is the complement of the probability that it is empty: p = 1 - e^(-λ). After amplification and reading, the ratio of positive partitions (k/n) is used to calculate λ using the rearranged equation: λ = -ln(1 - k/n) [26].

Quantification Accuracy and Optimal Partition Loading

The accuracy of dPCR quantification is statistically defined and depends heavily on the number of partitions and their loading efficiency. Intuitively, confidence in estimating target concentration is lowest when most partitions are either empty or full [26].

The optimal precision for quantification is achieved at a λ value of approximately 1.6, which corresponds to about 20% of partitions being negative (empty). This loading provides the optimal balance for statistical confidence in the concentration calculation [26]. The precision of the estimation scales with the inverse square root of the number of partitions, making higher partition counts statistically advantageous [26].

Figure 1: dPCR/ddPCR Workflow - From sample partitioning to absolute quantification.

Experimental Protocol: dPCR/ddPCR for ctDNA Detection

Pre-Analytical Phase: Sample Collection and Preparation

- Blood Collection: Collect 3 × 9 mL of patient blood into Streck Cell Free DNA BCT vacuum tubes or similar cell-free DNA blood collection tubes to prevent cell lysis and preserve ctDNA [27].

- Plasma Separation: Centrifuge blood tubes within 2 hours of collection using a two-step centrifugation protocol (e.g., 1,600 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C, followed by 16,000 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C) to obtain platelet-poor plasma.

- cfDNA Extraction: Extract cell-free DNA (cfDNA) from plasma using commercially available kits (e.g., QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid Kit). Elute in a low-EDTA TE buffer or the kit's elution buffer. Quantify cfDNA using fluorometric methods suitable for low-concentration samples.

- Sample Storage: Store extracted cfDNA at -80°C if not used immediately. Avoid multiple freeze-thaw cycles.

dPCR/ddPCR Assay Setup and Execution

- Assay Design: Design specific primers and probes (FAM/HEX) for target mutations identified through prior tumor sequencing [27]. For rare mutation detection, ensure probe specificity is validated against wild-type sequences.

- Reaction Mixture: Prepare 20-40 μL reaction volumes containing:

- 2-9 μL of extracted cfDNA template

- 1× ddPCR Supermix

- 900 nM of each primer

- 250 nM of each probe

- Partitioning: Generate 20,000 droplets using a droplet generator according to manufacturer's instructions. For ddPCR, the oil:water emulsion creates ~20,000 nanodroplets per sample [27].

- PCR Amplification: Transfer droplets to a 96-well PCR plate, seal, and run on a thermal cycler with the following typical conditions:

- Enzyme activation: 95°C for 10 minutes

- 40-45 cycles of: Denaturation: 94°C for 30 seconds; Annealing/Extension: 55-60°C for 60 seconds

- Enzyme deactivation: 98°C for 10 minutes

- Hold at 4°C

- Signal Reading: Transfer the PCR plate to a droplet reader which counts each droplet individually for fluorescence detection in each channel.

Data Analysis and Interpretation

- Threshold Setting: Set fluorescence thresholds for positive/negative droplets clearly between populations using the manufacturer's software. Optimize to minimize "rain" (droplets with intermediate fluorescence) [28].

- Quality Control: Apply the dMIQE guidelines to ensure publication-quality data [28]. Report the number of accepted droplets, template concentration, and confidence intervals.

- Concentration Calculation: Use the Poisson-corrected fraction of positive droplets to calculate the absolute concentration of the target (copies/μL) in the original sample:

- Target Concentration = -ln(1 - p) × (Total Droplets / Volume Analyzed)

- Where p is the fraction of positive droplets

- Variant Allele Frequency (VAF): For mutant detection, calculate VAF as:

- VAF = (Mutant Concentration / (Mutant + Wild-type Concentration)) × 100

Figure 2: Statistical Principles of dPCR - Poisson distribution and key factors affecting quantification accuracy.

Application in ctDNA Research: Protocol and Data

Tumor-Informed ctDNA Detection Protocol

This protocol is adapted from the rectal cancer study comparing ddPCR and NGS for ctDNA detection [27]:

- Tumor Sequencing: First, perform NGS sequencing of tumor tissue (e.g., using Ion AmpliSeq Cancer Hotspot Panel v2) to identify patient-specific mutations [27].

- Assay Selection: Based on tumor sequencing results, select 1-2 mutations with the highest variant allele frequencies for ddPCR assay design [27].

- Custom Probe Design: Design specific ddPCR assays using custom TaqMan probes for the identified mutations.

- Baseline Plasma Testing: Test baseline plasma samples collected before therapy initiation using the customized ddPCR assays.

- Longitudinal Monitoring: Collect follow-up plasma samples at defined timepoints (e.g., post-surgery, during adjuvant therapy) and analyze with the same ddPCR assays.

- Result Interpretation: Classify samples as ctDNA-positive if any detectable ctDNA is present (even one oncogenic mutation), and ctDNA-negative if no ctDNA is detected [27].

Performance Comparison in ctDNA Detection

| Parameter | ddPCR | NGS Panel | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Detection Rate (Development Group) | 24/41 (58.5%) | 15/41 (36.6%) | p = 0.00075 |

| Detection Rate (Validation Group) | 21/26 (80.8%) | Not reported | Not applicable |

| Association with Clinical Factors | Higher clinical tumor stage, lymph node positivity | Similar associations | Clinically relevant |

| Postoperative Detection | Limited detection before recurrences | Not reported | Needs optimization |

| Operational Costs | 5–8.5-fold lower than NGS [27] | Higher | Cost-effective |

Advantages for ctDNA Analysis

- High Sensitivity: ddPCR detects somatic alterations at low frequencies down to 0.01% variant allele frequency (VAF) [27], making it suitable for ctDNA detection where tumor DNA represents a small fraction of total cell-free DNA.

- Cost-Effectiveness: The operational costs of ctDNA detection with ddPCR are 5–8.5-fold lower than with NGS [27].

- Absolute Quantification: Provides direct measurement of mutant allele concentration without reference standards, enabling precise monitoring of treatment response.

- Tolerance to Inhibitors: Sample partitioning reduces the effect of PCR inhibitors present in clinical samples, improving reliability [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Materials for dPCR/ddPCR ctDNA Research

| Item | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Cell-Free DNA Blood Collection Tubes | Preserves blood sample integrity, prevents cell lysis during transport/storage | Streck Cell-Free DNA BCT tubes [27] |

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits | Isolation of high-quality cfDNA from plasma samples | QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid Kit |

| dPCR/ddPCR Supermix | Optimized reaction buffer for partitioning and amplification | ddPCR Supermix for Probes |

| Custom TaqMan Assays | Mutation-specific detection with fluorescent probes | Primer/probe sets for target mutations |

| Droplet Generation Oil | Creates stable water-in-oil emulsion for partitioning | Droplet Generation Oil for Probes |

| dPCR Plates and Sealers | Reaction containment during thermal cycling | 96-well dPCR plates, pierceable foil seals |

| Quantitative Reference Standards | Assay validation and quality control | Synthetic DNA standards with known mutations |

| Bioinformatic Analysis Software | Data analysis, threshold setting, concentration calculation | Manufacturer-specific analysis packages |

The detection and measurement of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) is a cornerstone of modern liquid biopsy applications, from monitoring treatment response to detecting minimal residual disease (MRD). The choice between quantitative PCR (qPCR) and digital PCR (dPCR) fundamentally shapes experimental design and data interpretation, revolving around a core methodological distinction: relative versus absolute quantification.

Relative quantification, employed by qPCR, measures target amount relative to a standard curve or control gene. In contrast, absolute quantification, achieved through dPCR, provides an exact count of target molecules without external calibration [29]. This technical distinction profoundly impacts assay sensitivity, precision, and utility in clinical cancer research, particularly for detecting rare ctDNA molecules against a background of wild-type DNA.

Core Principles: qPCR and dPCR Operational Mechanisms

Quantitative PCR (qPCR) and Relative Quantification

qPCR operates by monitoring PCR amplification in real-time, measuring the cycle threshold (Ct) at which fluorescence crosses a detection threshold. The Ct value is inversely proportional to the starting quantity of the target nucleic acid [29].

- Relative Quantification Framework: qPCR results are expressed relative to a standard curve constructed from samples with known concentrations, or normalized to an endogenous control gene. This provides a relative measure of change (e.g., fold-difference) rather than an absolute molecule count [29].

- Measurement Phase: Data collection occurs during the exponential amplification phase where the amount of PCR product approximately doubles each cycle, providing the most accurate correlation between Ct and starting quantity [29].

Digital PCR (dPCR) and Absolute Quantification

dPCR takes a fundamentally different approach by partitioning a sample into thousands of individual reactions. After endpoint amplification, the ratio of positive to negative partitions is counted [30].

- Absolute Quantification Framework: Using Poisson statistics, this ratio directly calculates the absolute number of target molecules in the original sample without requiring a standard curve [29] [30].

- Partitioning Technology: Current commercial platforms achieve partitioning via microchips (e.g., QuantStudio 12K Flex, BioMark HD) or water-in-oil droplets (e.g., QX200 from Bio-Rad) [30].

The table below summarizes the key technical distinctions between these approaches:

Table 1: Fundamental Operational Differences Between qPCR and dPCR

| Parameter | Quantitative PCR (qPCR) | Digital PCR (dPCR) |

|---|---|---|

| Quantification Type | Relative | Absolute |

| Calibration Requirement | Requires standard curve | No standard curve needed |

| Measurement Principle | Cycle threshold (Ct) during exponential phase | Positive/Negative partition count at endpoint |

| Data Output | Relative quantity or fold-change | Exact copy number per input volume |

| Impact of Amplification Efficiency | Highly sensitive to efficiency variations | Less affected by efficiency variations |

| Ideal Application Scope | Gene expression, pathogen load with abundant targets | Rare allele detection, liquid biopsy, viral load at low concentrations |

Visualizing the Workflow Divergence

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental procedural differences between the two quantification methodologies:

Performance Comparison in ctDNA Analysis

Sensitivity and Precision for Low Abundance Targets

ctDNA analysis presents a singular challenge: detecting extremely rare mutant alleles within a vast background of wild-type cell-free DNA. In this context, dPCR's absolute quantification provides decisive advantages:

- Superior Sensitivity for Rare Alleles: dPCR's partitioning effectively enriches low-frequency targets, enabling detection of variants at variant allele frequencies (VAF) as low as 0.01% under optimal conditions [27] [31]. This is crucial for MRD detection where ctDNA levels can be minuscule.

- Enhanced Precision at Low Concentrations: dPCR demonstrates significantly improved precision for quantifying low-copy number targets, a critical factor for reliable ctDNA monitoring [30]. This precision is maintained even with suboptimal amplification efficiency, whereas qPCR quantification accuracy depends heavily on high, consistent efficiency [30].

- Direct Comparison Evidence: A 2025 performance comparison in rectal cancer patients demonstrated that ddPCR detected ctDNA in 58.5% (24/41) of baseline plasma samples, significantly outperforming an NGS panel which detected ctDNA in only 36.6% (15/41) of the same samples (p=0.00075) [27].

Tolerance to Sample Inhibitors and PCR Efficiency

Complex biological samples like plasma often contain substances that can inhibit PCR amplification, potentially compromising results:

- Robustness Against Inhibitors: dPCR has demonstrated greater tolerance to PCR inhibitors present in clinical samples because endpoint detection is less affected than the reaction kinetics measured in qPCR [30].

- Efficiency Independence: qPCR quantification assumes near-perfect amplification efficiency (接近 100%), which is not always achievable. dPCR, relying on binary endpoint detection, provides accurate absolute quantification even with reduced amplification efficiency [30].

Table 2: Analytical Performance Comparison for ctDNA Detection

| Performance Characteristic | qPCR | dPCR | Implication for ctDNA Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Limit of Detection (VAF) | ~1-5% | ~0.01%-0.1% | dPCR enables MRD and early-stage cancer detection |

| Precision (Low Target) | Moderate | High | More reliable tracking of molecular response |

| Impact of Inhibitors | Significant | Reduced | More robust with difficult sample matrices |

| Dependence on Amplification Efficiency | Critical | Minimal | More accurate quantification with suboptimal reactions |

| Multiplexing Capability | High (4-6 colors) | Limited (typically 2 colors) | qPCR advantageous for multi-gate panels |

| Dynamic Range | Wide (6-8 logs) | Moderate (due to partition count) | qPCR better for quantifying high-concentration targets |

Experimental Protocols for ctDNA Quantification

Protocol: Tumor-Informed ctDNA Detection via ddPCR

This protocol outlines a tumor-informed approach where mutations identified in tumor tissue are tracked in plasma using mutation-specific ddPCR assays [27] [32].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Kit | Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Streck Cell-Free DNA BCT Tubes | Blood collection for plasma stabilization | Preserves cfDNA by inhibiting nuclease activity and cell lysis [27] |

| QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid Kit | cfDNA extraction from plasma | High-sensitivity recovery of short-fragment cfDNA [33] |

| ddPCR Supermix for Probes (Bio-Rad) | PCR reaction mixture for droplet generation | Optimized for water-in-oil droplet formation and stability |

| Mutation-Specific TaqMan Assays | Target-specific probe and primer sets | Custom-designed for patient-specific mutations; FAM/HEX labeled |

| Droplet Generation Oil | Creation of water-in-oil emulsion | Critical for partition formation in QX200 systems |

| dgDNA/UDG Enzyme Treatment | Prevention of carryover contamination | Degrades contaminating amplicons from previous PCR runs |

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Sample Collection and Processing: Collect patient blood in Streck Cell-Free DNA BCT tubes (e.g., 3 × 9 mL tubes) [27]. Centrifuge within 96 hours to isolate plasma. Perform a second high-speed centrifugation (e.g., 12,000 × g for 10 min) to remove residual cells [33].

- cfDNA Extraction: Extract cfDNA from 2-4 mL of plasma using the QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid Kit or equivalent. Elute in a low volume (e.g., 30-50 µL) of TE buffer or nuclease-free water. Quantify using a fluorescence-based assay (e.g., Qubit dsDNA HS Assay) [33].

- Assay Design: For tumor-informed detection, identify somatic mutations (e.g., SNVs, Indels) from primary tumor sequencing (e.g., using an Ion AmpliSeq Cancer Hotspot Panel v2) [27]. Design and validate custom TaqMan ddPCR assays for 1-2 mutations with the highest variant allele frequency in the tumor.

- ddPCR Reaction Setup: Prepare a 20-22 µL reaction mixture containing:

- 10-20 ng of extracted cfDNA (or equivalent volume if low yield)

- 1× ddPCR Supermix for Probes

- 900 nM of each primer

- 250 nM of each FAM/HEX-labeled probe

- Droplet Generation: Load the reaction mixture into a DG8 Cartridge of a QX200 Droplet Generator along with Droplet Generation Oil. This creates approximately 20,000 nanodroplets per sample [27].

- PCR Amplification: Transfer the generated droplets to a 96-well plate. Seal the plate and perform PCR amplification on a thermal cycler using optimized cycling conditions (e.g., 95°C for 10 min, 40 cycles of 94°C for 30 sec and 55-60°C for 60 sec, 98°C for 10 min, 4°C hold).

- Droplet Reading and Analysis: Read the plate on a QX200 Droplet Reader. Analyze the data using QuantaSoft software. Set thresholds to distinguish positive and negative droplets for each channel. The software uses Poisson statistics to calculate the absolute concentration (copies/µL) of the target mutation in the original reaction [29].

- Result Interpretation: A sample is deemed ctDNA-positive if any detectable target mutation is present above a pre-defined threshold (e.g., ≥ 2 positive droplets for the mutant allele) [27]. Report mutant copies per mL of plasma for clinical correlation.

Protocol: Tumor-Agnostic ctDNA Detection via qPCR-based NGS Panel

This protocol uses a tumor-agnostic NGS panel with qPCR-based library quantification, suitable for detecting a defined set of mutations without prior tumor sequencing [33].

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Sample Collection and cfDNA Extraction: Follow identical steps as in the ddPCR protocol (Steps 1-2) to obtain purified cfDNA.

- Library Preparation: Use a targeted NGS panel (e.g., Oncomine Breast cfDNA Assay covering 150 hotspots in 10 genes) with 10-20 ng input cfDNA [33]. Prepare sequencing libraries per manufacturer's instructions, incorporating barcodes for sample multiplexing.

- Library Quantification via qPCR: Quantify the final library concentration using a qPCR-based method (e.g., Kapa Library Quantification Kit). This step is critical for determining optimal loading concentration for sequencing and inherently relies on relative quantification against a DNA standard curve.

- Next-Generation Sequencing: Pool libraries and sequence on an appropriate platform (e.g., Ion GeneStudio S5 or Illumina MiSeq/NextSeq) to achieve high sequencing depth (e.g., median >20,000× coverage) [33].

- Bioinformatic Analysis and Variant Calling: Align sequences to the reference genome. Call variants using the panel's specific bioinformatics pipeline. A variant is typically called positive if its VAF is above the assay's limit of detection (LOD), which must be empirically determined for each variant type [34].

Application Contexts: Guiding Method Selection

The choice between qPCR and dPCR is dictated by the specific research question and context:

- Minimal Residual Disease (MRD) and Early Recurrence: dPCR is the preferred method due to its superior sensitivity for detecting very low VAF ctDNA (<0.1%) [31]. In melanoma, baseline ctDNA detection by ddPCR was a powerful prognostic biomarker, identifying patients with high recurrence risk [32].

- Treatment Response Monitoring: Both technologies can track dynamic changes. dPCR offers superior precision for small fold-changes, while qPCR-NGS panels can monitor multiple mutations simultaneously, providing a broader view of clonal evolution [31].

- Genotyping in Advanced Disease: For characterizing known actionable mutations at higher VAF, qPCR-based NGS panels offer a cost-effective solution for screening multiple genomic regions simultaneously [34].

The distinction between relative (qPCR) and absolute (dPCR) quantification is more than technical—it defines the boundaries of possible research and clinical applications in ctDNA analysis. dPCR provides the sensitivity, precision, and absolute quantification necessary for the most challenging applications like MRD detection and early intervention studies. Conversely, qPCR and its NGS derivatives offer a broader, more efficient screening platform for genotyping and monitoring higher VAF targets. The informed researcher must align their quantification choice with their biological question, leveraging the strengths of each platform to advance the paradigm of liquid biopsy in oncology.

Methodology in Action: Implementing dPCR and qPCR for ctDNA Analysis

The analysis of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) has emerged as a powerful, minimally invasive tool in oncology, enabling applications from early cancer detection to therapeutic monitoring [35]. ctDNA consists of short, fragmented DNA molecules shed by tumors into the bloodstream, which typically represent only a small fraction (0.1% to over 10%) of the total cell-free DNA (cfDNA) in cancer patients [36] [35]. Detecting these rare mutations requires highly sensitive and robust molecular techniques. This application note provides a detailed comparison of two primary technologies used for ctDNA analysis: Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qPCR) and Digital PCR (dPCR), framing their workflows from initial sample collection through final data analysis. The focus is placed on their application within clinical research settings for drug development and cancer management.

Digital PCR (dPCR) works by partitioning a PCR reaction into thousands of individual nanoreactions. After endpoint amplification, each partition is analyzed as positive or negative for the target, allowing for absolute quantification of the target molecule without the need for a standard curve [37] [5]. This partitioning enhances sensitivity and resistance to PCR inhibitors, making dPCR particularly suited for detecting rare mutations and targets present at low concentrations [36] [5].

Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qPCR) monitors the amplification of a target DNA sequence in real-time using fluorescent reporters. The cycle threshold (Cq) at which fluorescence crosses a defined level is used for relative quantification, typically with the aid of a standard curve [37] [5]. While qPCR is a versatile and high-throughput method, its sensitivity for detecting very rare mutant alleles in a high background of wild-type DNA can be limited [38] [5].

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of both platforms in the context of ctDNA analysis:

Table 1: Performance Comparison of dPCR and qPCR for ctDNA Detection

| Feature | Digital PCR (dPCR) | Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qPCR) |

|---|---|---|

| Principle of Quantification | Absolute, by direct counting of molecules [5] | Relative, requires a standard curve [5] |

| Sensitivity for Rare Mutations | High; can detect mutant allele frequencies as low as 0.1% [36] | Lower; sensitive to background noise from wild-type DNA [38] |

| Dynamic Range | Narrower [5] | Wide (6-7 orders of magnitude) [5] |

| Throughput | Lower [5] | High (compatible with 384-well plates) [5] |

| Cost per Reaction | Higher [5] | Lower [5] |

| Robustness to PCR Inhibitors | High (partitioning dilutes inhibitors) [5] | Sensitive [5] |

| Ideal Application in ctDNA Research | Rare mutation detection, low-abundance target quantification, liquid biopsy [36] [35] | High-throughput screening, gene expression, pathogen detection [5] |

Experimental Protocols

Pre-Analytical Sample Processing

The pre-analytical phase is critical for obtaining high-quality, reliable ctDNA data, as cfDNA is present in low concentrations and can be easily contaminated or degraded.

- Sample Collection: Blood should be collected in tubes containing stabilizers that prevent the lysis of white blood cells and preserve the cfDNA profile, such as cell-free DNA BCT tubes or ACD tubes [39]. The sample should be inverted gently several times to ensure proper mixing with the preservative.

- Plasma Separation: Plasma must be separated within a strict timeframe to ensure sample integrity, typically within 1 to 4 hours of collection if using standard EDTA tubes, or up to several days if using specialized cfDNA BCT tubes [39]. A two-step centrifugation protocol is recommended:

- First Spin: A low-speed centrifugation (e.g., 800-1,600 × g for 10-20 minutes at room temperature) to separate plasma from whole blood cells.

- Second Spin: The transferred plasma is subjected to a high-speed centrifugation (e.g., 16,000 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C) to remove any remaining cellular debris and platelets [39].

- cfDNA Extraction: The clarified plasma is then used for cfDNA extraction. Magnetic bead-based methods are widely adopted due to their high recovery rates, automation compatibility, and ability to produce high-quality cfDNA with a characteristic mononucleosomal size peak of ~167 base pairs [39]. The extraction should be performed according to the manufacturer's protocol, and the final eluate should be stored at -20°C or -80°C until analysis.

- Quality Control (QC): Extracted cfDNA should be quantified and assessed for quality. Fluorometric methods (e.g., Qubit) are preferred over spectrophotometry for accurate concentration measurement. Fragment analyzers (e.g., Agilent TapeStation) can confirm the size distribution of cfDNA and check for contamination with high molecular weight genomic DNA, which can interfere with downstream assays [39] [40].

Protocol A: Detection of KRAS Mutations via PNB-qPCR

This protocol, derived from a published study, describes a highly sensitive nested qPCR approach with wild-type blocking to detect low-frequency KRAS mutations [38].

- Step 1: First-Round PCR with WT Blocking

- Objective: To selectively enrich mutant KRAS alleles from a background of wild-type DNA.

- Reaction Setup: Prepare a PCR mix containing the extracted cfDNA template, primers specific for the KRAS exon 2 region, and wild-type (WT) specific blocking primers. These blocking primers, which can be peptide nucleic acid (PNA) or locked nucleic acid (LNA) clamps, hybridize preferentially to the wild-type sequence and suppress its amplification during the PCR, thereby enriching the mutant targets [38].

- Thermal Cycling: Perform a standard PCR amplification protocol.

- Step 2: Product Pooling

- To reduce variance and improve quantification accuracy, the protocol recommends setting up five separate first-round PCR reactions for each sample. After amplification, the products of these five reactions are pooled together [38].

- Step 3: Second-Round Quantitative PCR

- Objective: To specifically detect and quantify the enriched mutant alleles.

- Reaction Setup: Use the pooled first-round product as a template for a qPCR reaction. The qPCR employs mutation-specific ARMS (Amplification Refractory Mutation System) primers and short LNA probes to ensure high specificity for the seven most frequent KRAS point mutations in exon 2 [38].

- Data Analysis: The cycle of quantification (Cq) is determined. A standard curve, generated using synthetic DNA standards with known mutations, is used for absolute quantification. The PNB-qPCR method has demonstrated a limit of quantification (LOQ) as low as 6.25 copies and can detect a mutant allele frequency of 0.003% (1 mutant in 30,000 WT copies) [38].

Protocol B: Absolute Quantification of ctDNA using Digital PCR

This protocol outlines a standard dPCR workflow for the absolute quantification of known somatic mutations in ctDNA, such as those in the PIK3CA or ESR1 genes in breast cancer [36] [35].

- Step 1: Assay Preparation

- Assay Selection: For known mutations, use pre-validated, sequence-specific assays, such as TaqMan probe-based assays [36]. These are available as pre-formulated kits (e.g., Absolute Q Liquid Biopsy dPCR assays) or can be custom-designed.

- Reaction Setup: Prepare a dPCR reaction mix containing the master mix, fluorescently labeled probes (e.g., FAM for mutant, VIC for wild-type), and the extracted cfDNA sample.

- Step 2: Partitioning

- Step 3: Endpoint PCR Amplification

- The partitioned plate or cartridge is placed in a thermal cycler and run through a standard PCR protocol to endpoint amplification.

- Step 4: Data Acquisition and Analysis

- Reading: The dPCR instrument scans each partition for fluorescence signals.

- Analysis: Software is used to count the positive and negative partitions for each fluorescent channel. The concentration of the target mutant and wild-type DNA in the original sample (in copies/µL) is calculated using Poisson statistics. The variant allele frequency (VAF) is then determined as (mutant concentration / total DNA concentration) × 100%. Platforms like the QuantStudio Absolute Q system can detect VAFs as low as 0.1% [36].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the core procedural differences between the qPCR and dPCR workflows for ctDNA analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit

The table below lists key reagents and materials essential for conducting ctDNA analysis, as referenced in the protocols above.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for ctDNA Analysis

| Item | Function / Application | Examples / Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| cfDNA Blood Collection Tubes | Stabilizes nucleated blood cells to prevent genomic DNA contamination and preserve cfDNA profile for longer periods before processing. | Cell-free DNA BCT tubes (e.g., from Streck) [39] |

| Magnetic Bead-based cfDNA Kits | High-efficiency extraction of short, low-concentration cfDNA fragments from plasma; automatable. | Kits from various manufacturers (e.g., nRichDx, QIAamp) [39] |

| dPCR Master Mix & Assays | Optimized reagents and pre-designed probes for sensitive and specific mutation detection on dPCR platforms. | Absolute Q Liquid Biopsy dPCR Assays, TaqMan dPCR Master Mix [36] |

| Reference Standards | Controls for assay validation, determining recovery rates, limit of detection, and quantification accuracy. | Seraseq ctDNA, AcroMetrix ctDNA plasma controls [39] |

| Fragment Analyzer | Quality control instrument to assess cfDNA size profile and check for high molecular weight gDNA contamination. | Agilent TapeStation system [39] |

| LNA/PNA Clamping Oligos | Synthetic nucleic acids used in qPCR to suppress wild-type DNA amplification, enriching for mutant sequences. | Used in PNB-qPCR and similar methods [38] |

Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) consists of small fragments of DNA released by tumor cells into the bloodstream and other bodily fluids. As a minimally invasive real-time biomarker, ctDNA reflects overall tumor burden and molecular heterogeneity, offering significant advantages over traditional tissue biopsies [41]. The short half-life of ctDNA (estimated between 16 minutes to several hours) enables dynamic monitoring of treatment response and disease progression, enabling near real-time assessment of tumor dynamics [1]. These characteristics make ctDNA particularly valuable for two critical applications in oncology: monitoring treatment response and detecting minimal residual disease (MRD) – the presence of microscopic disease after curative-intent therapy that precedes clinical recurrence [42] [1].

The detection and analysis of ctDNA require highly sensitive molecular techniques due to its typically low concentration in circulation, especially in early-stage cancers and MRD settings where tumor DNA may constitute less than 0.1% of total cell-free DNA [42] [1]. This technical note examines the application of ctDNA analysis in treatment monitoring and MRD detection, with particular emphasis on the comparative performance of digital PCR (dPCR) and quantitative PCR (qPCR) methodologies.