Liquid Biopsy in Cancer Monitoring: Advanced Techniques, Clinical Applications, and Future Directions for Research and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive overview of liquid biopsy technologies for cancer monitoring, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Liquid Biopsy in Cancer Monitoring: Advanced Techniques, Clinical Applications, and Future Directions for Research and Drug Development

Abstract

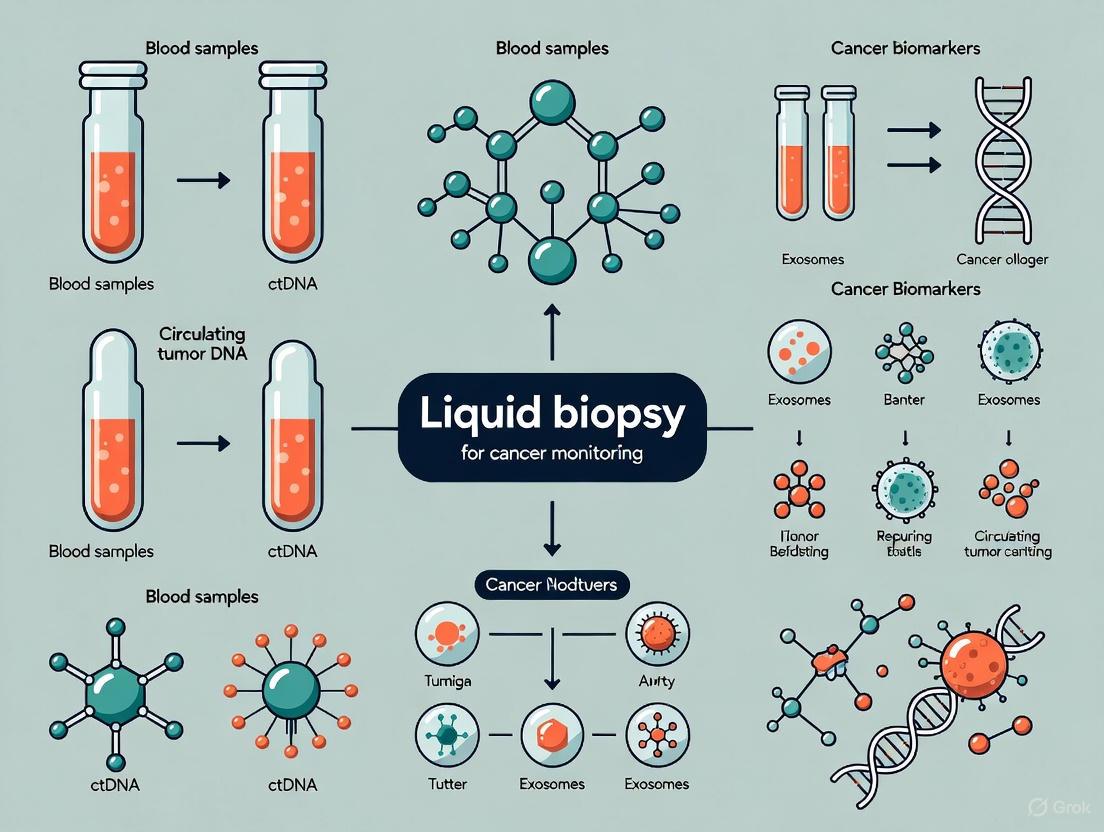

This article provides a comprehensive overview of liquid biopsy technologies for cancer monitoring, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational biology of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA), circulating tumor cells (CTCs), and other biomarkers. The scope encompasses current and emerging methodological approaches—including next-generation sequencing (NGS), digital PCR, and microfluidic isolation—along with their applications in therapy selection, minimal residual disease (MRD) detection, and tracking resistance. The content also addresses key challenges such as assay optimization, confounding factors like clonal hematopoiesis, and the critical validation frameworks necessary for clinical translation and comparative performance assessment against tissue biopsy.

The Foundation of Liquid Biopsy: Core Biomarkers and Biological Principles for Cancer Monitoring

Circulating Tumor DNA (ctDNA)

Core Characteristics and Biological Significance

Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) refers to small fragments of tumor-derived DNA circulating in the bloodstream, representing a subset of total cell-free DNA (cfDNA). These fragments are released into the circulation primarily through apoptosis and necrosis of tumor cells [1] [2]. ctDNA carries tumor-specific genetic and epigenetic alterations, including single nucleotide variants (SNVs), structural variants (SVs), copy number alterations, and methylation changes, providing a comprehensive molecular portrait of the tumor [1] [2]. A key advantage of ctDNA is its short half-life, estimated between 16 minutes to several hours, which enables real-time monitoring of tumor dynamics and treatment response [2]. The fraction of ctDNA in total cfDNA varies significantly with disease burden, ranging from below 0.1% in early-stage cancers to over 90% in advanced metastatic disease, creating substantial detection challenges particularly for minimal residual disease (MRD) assessment [1].

Current Detection Technologies and Methodologies

Advanced technologies have been developed to address the sensitivity challenges in ctDNA detection, particularly for low-frequency variants and MRD monitoring.

Table 1: Key Analytical Platforms for ctDNA Detection

| Technology Platform | Key Principle | Sensitivity Range | Primary Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ddPCR/BEAMing | Partitioning of DNA fragments for absolute quantification | ~0.01% VAF | Tracking known mutations, therapy monitoring | High sensitivity, absolute quantification, rapid turnaround | Limited to small number of pre-defined mutations |

| Structural Variant (SV) Assays | Detection of tumor-specific chromosomal rearrangements | <0.01% VAF (parts-per-million) | MRD, early-stage cancer detection | Ultra-high sensitivity, tumor-specific markers | Requires personalized assay design |

| Targeted NGS (CAPP-Seq, TEC-Seq) | Hybrid capture with error correction | 0.01%-0.1% VAF | Comprehensive mutation profiling, resistance monitoring | Broad genomic coverage, high specificity | Higher cost, complex bioinformatics |

| Magnetic Nano-electrode Systems | Electrochemical sensing with nanoparticle enrichment | Attomolar (10¯¹⁸ M) | Point-of-care applications, rapid detection | Extreme sensitivity, minimal processing | Still in development phase |

| PhasED-Seq | Detection of multiple phased variants on same DNA fragment | Ultra-high sensitivity (<0.0001%) | MRD, ultra-early recurrence | Exceptional sensitivity for very low ctDNA | Complex assay design |

Applications in Cancer Monitoring and Research

ctDNA analysis has transformed multiple aspects of cancer management through non-invasive liquid biopsy approaches. In treatment response monitoring, ctDNA levels provide a dynamic and quantitative measure of tumor burden, often demonstrating changes earlier than radiographic imaging [1] [2]. Studies in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and colorectal cancer have shown that ctDNA decline following therapy initiation accurately predicts radiographic response and improved survival outcomes [1]. For minimal residual disease (MRD) assessment, ctDNA detection after curative-intent surgery or completion of adjuvant therapy identifies patients at high risk of recurrence, often months to years before clinical manifestation [1] [2]. In breast cancer, SV-based ctDNA assays detected molecular recurrence more than one year before clinical evidence of disease [1]. Additionally, ctDNA enables noninvasive genotyping and therapy resistance monitoring, identifying emerging resistance mutations to targeted therapies (e.g., T790M in EGFR-mutant NSCLC) without repeated tissue biopsies [1]. Emerging applications include methylation profiling for tumor agnostic detection and fragmentomics analysis, which leverages ctDNA fragmentation patterns to distinguish tumor-derived DNA from normal cfDNA [1] [2].

Detailed Protocol: Structural Variant-Based ctDNA Detection for MRD

Principle: This tumor-informed approach identifies patient-specific structural variants (translocations, insertions, deletions) through baseline tumor tissue sequencing, then designs personalized hybrid-capture probes or multiplexed PCR panels to detect these rearrangements in plasma with ultra-high sensitivity [1].

Workflow:

- Tumor Tissue Sequencing: Perform whole-genome or whole-exome sequencing on baseline tumor tissue to identify tumor-specific structural variants with breakpoint sequences.

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Identify optimal SV targets (typically 1-16 variants) with unique breakpoint sequences not present in normal germline DNA.

- Panel Design: Design custom hybrid-capture baits or PCR primers flanking each breakpoint.

- Plasma Collection and Processing:

- Collect 10-20 mL blood in cell-free DNA collection tubes (e.g., Streck, PAXgene)

- Process within 6 hours of collection: centrifuge at 1600 × g for 10 min to separate plasma, then 16,000 × g for 10 min to remove residual cells

- Extract cfDNA using silica-membrane columns (QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid Kit)

- Quantify using fluorometry (Qubit dsDNA HS Assay)

- Library Preparation and Sequencing:

- Construct sequencing libraries with unique molecular identifiers (UMIs)

- Enrich for target regions using custom baits/primers

- Sequence to high depth (>100,000X) on Illumina platform

- Variant Calling and Quantification:

- Align sequences to reference genome

- Group reads by UMI to create consensus sequences

- Identify breakpoint-spanning reads

- Calculate variant allele frequency (VAF)

Quality Control:

- Input cfDNA: ≥10 ng recommended

- Spike-in synthetic controls for extraction efficiency monitoring

- Negative controls (healthy donor plasma) for background estimation

- Limit of detection: Establish using dilution series of tumor DNA in normal plasma

Figure 1: SV-based ctDNA MRD Detection Workflow

Circulating Tumor Cells (CTCs)

Core Characteristics and Biological Significance

Circulating tumor cells (CTCs) are intact cancer cells that detach from primary or metastatic tumors and enter the bloodstream, playing a crucial role in cancer metastasis [3] [4]. First identified in 1869, CTCs represent a rare population amidst billions of blood cells, with concentrations as low as 1 CTC per billion hematological cells in early-stage cancer [3]. These cells exhibit remarkable heterogeneity, encompassing epithelial, mesenchymal, and hybrid phenotypes resulting from epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), which enhances their invasive capabilities and metastatic potential [3] [4]. CTCs can circulate as single cells or clusters (circulating tumor microemboli) and often display stem-like characteristics with self-renewal capacity [3]. Unlike ctDNA, CTCs provide comprehensive biological information including genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and functional data from viable tumor cells, offering unique insights into metastatic biology and therapeutic targets [3] [4].

Current Detection Technologies and Methodologies

CTC isolation and detection strategies leverage both biological and physical properties to overcome the challenge of extreme rarity in blood samples.

Table 2: CTC Isolation and Detection Platforms

| Technology Category | Specific Platforms/Methods | Isolation Principle | Recovery Efficiency | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biological Properties-Based | CellSearch (FDA-approved) | Immunomagnetic enrichment (EpCAM) | Variable (40-90%) | Clinical validation, standardization | Misses EMT CTCs (EpCAM-negative) |

| MACS | Magnetic cell sorting | Moderate | High purity | Limited by antibody specificity | |

| FACS | Fluorescence-activated sorting | High | Single-cell resolution | Low throughput, equipment cost | |

| Physical Properties-Based | ISET (Rarecells) | Size-based filtration (8μm pores) | High | Marker-independent, preserves cell viability | May miss small CTCs |

| Parsortix | Size and deformability | Moderate | Downstream molecular analysis | Clogging potential | |

| Dean Flow Fractionation | Inertial focusing | High | High throughput | Complex microfluidics | |

| Microfluidic/Chip-Based | CTC-iChip | Inertial sorting + immunomagnetic | High | High recovery, marker-independent | Technical complexity |

| HB-Chip | Hemodynamic sorting | Moderate | Simple operation | Lower purity | |

| Functional Assays | EPISPOT assay | Protein secretion detection | Low | Viable CTC detection | Complex, low throughput |

Applications in Cancer Monitoring and Research

CTC enumeration and characterization provide valuable clinical insights across cancer types. As a prognostic biomarker, CTC counts consistently correlate with clinical outcomes. In metastatic breast, prostate, and colorectal cancers, elevated CTC counts (using CellSearch system) are associated with significantly reduced progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) [3] [4]. For therapy monitoring, dynamic changes in CTC counts during treatment provide early indication of response or resistance, often preceding radiographic assessment [4]. In treatment selection, molecular characterization of CTCs can identify actionable targets and resistance mechanisms through protein expression analysis, fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), and next-generation sequencing [3]. Emerging applications include functional studies through in vitro CTC culture and CTC-derived xenograft (CDX) models, which enable drug sensitivity testing and investigation of metastasis mechanisms [4]. CTC clusters, while less frequent than single CTCs, demonstrate significantly enhanced metastatic potential and are associated with poorer patient outcomes [3].

Detailed Protocol: Integrated Microfluidic CTC Capture and Molecular Analysis

Principle: This protocol combines size-based enrichment with immunoaffinity capture for comprehensive CTC isolation, followed by molecular characterization using single-cell RNA sequencing.

Workflow:

- Blood Collection and Processing:

- Collect 10-15 mL peripheral blood in EDTA or CellSave tubes

- Process within 4-24 hours (depending on preservative)

- Initial centrifugation: 800 × g for 20 min with density gradient (Ficoll-Paque) to separate peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs)

Microfluidic CTC Enrichment:

- Prime microfluidic chip (e.g., CTC-iChip, Herringbone Chip) with PBS + 1% BSA

- Load PBMC fraction at controlled flow rate (1-2 mL/h)

- For immunomagnetic depletion: Incubate with CD45 magnetic beads to remove leukocytes

- Collect CTC-enriched fraction in collection buffer

CTC Identification and Enumeration:

- Cytocentrifugation onto glass slides

- Immunofluorescence staining:

- Epithelial markers: Pan-cytokeratin (CK 8,18,19) - Alexa Fluor 488

- Leukocyte marker: CD45 - Alexa Fluor 647 (exclusion)

- Nuclear stain: DAPI

- Microscopic analysis: Identify CTCs as CK+/DAPI+/CD45- cells

Single-Cell Isolation and Molecular Analysis:

- Manual picking or automated cell sorting (e.g., DEPArray, FACS)

- Single-cell whole transcriptome amplification (Smart-seq2 protocol)

- Library preparation and RNA sequencing (Illumina platform)

- Bioinformatic analysis for gene expression profiling and mutation detection

Alternative Workflow for Culture:

- Resuspend CTC-enriched fraction in CTC culture medium (RPMI-1640 + 10% FBS + growth factors)

- Plate in ultra-low attachment plates

- Monitor for CTC cluster formation and sphere growth

- Expand for drug sensitivity testing or CDX model generation

Quality Control:

- Blood processing: Maintain at room temperature, avoid refrigeration

- Spike-in controls: Add known number of tumor cells (e.g., SKBR3, MCF-7) to healthy donor blood for recovery assessment

- Purity assessment: Calculate ratio of CTCs to contaminating leukocytes

- Viability: >70% for successful culture attempts

Figure 2: Comprehensive CTC Analysis Workflow

Extracellular Vesicles (EVs)

Core Characteristics and Biological Significance

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are heterogeneous, membrane-bound particles secreted by various cell types, playing crucial roles in intercellular communication through transfer of proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids [5]. According to MISEV2018 and MISEV2023 guidelines, EVs are broadly categorized by size and biogenesis into small extracellular vesicles (sEVs; <200 nm, including exosomes) and large extracellular vesicles (>200 nm, including microvesicles and apoptotic bodies) [5]. sEVs form through inward budding of the endosomal membrane, creating intraluminal vesicles within multivesicular bodies that subsequently fuse with the plasma membrane [5]. Microvesicles (200-1000 nm) generate through direct outward budding from the plasma membrane, while apoptotic bodies (1-5 μm) release during programmed cell death [5]. Tumor-derived EVs (tEVs) carry diverse biomolecules reflecting their parent cells, offering valuable insights into tumor presence and progression [5]. Key advantages of EV-based liquid biopsy include their higher concentration in bodily fluids compared to CTCs, exceptional biological stability even within harsh tumor microenvironments, and comprehensive molecular information surpassing circulating DNA [5].

Current Detection Technologies and Methodologies

EV isolation and characterization require specialized approaches to address challenges related to their small size, heterogeneity, and co-isolation with non-vesicular particles.

Table 3: EV Isolation and Analysis Techniques

| Isolation Method | Principle | Purity | Yield | Downstream Applications | Throughput |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ultracentrifugation | Sequential centrifugation forces | Moderate | High | Proteomics, RNA sequencing | Low |

| Size-Exclusion Chromatography | Size-based separation in columns | High | Moderate | Functional studies, biomarker discovery | Medium |

| Precipitation (ExoQuick) | Polymer-based aggregation | Low | High | RNA/protein analysis | High |

| Immunoaffinity Capture | Antibody-based (CD63, CD81, CD9) | High | Low | Subtype characterization, specific marker studies | Low |

| Microfluidic Devices | Immunoaffinity or size-based on chip | High | Moderate | Point-of-care applications | Medium |

| Asymmetric Flow FFF | Field-flow fractionation | High | Moderate | Size characterization, omics studies | Low |

Applications in Cancer Monitoring and Research

EV-based liquid biopsy demonstrates extensive potential applications in disease diagnosis, prognosis evaluation, and treatment monitoring [5]. For cancer diagnostics, EV biomarkers enable early detection across multiple cancer types. In hepatocellular carcinoma, elevated levels of Glypican-3 (GPC3) in circulating EVs serve as reliable indicators for early detection [5]. Microfluidic digital PCR platforms enable accurate quantification of tumor-derived sEVs across various tumor markers with exceptional sensitivity (detection limit: 10 copies) [5]. In therapeutic monitoring, EV cargo analysis provides dynamic insights into treatment response and resistance mechanisms. For disease subtyping, EV molecular profiles help classify cancer subtypes and monitor tumor evolution through serial liquid biopsies [5]. EVs also show promise in autoimmune diseases and infectious diseases through specific biomarker detection [5]. Beyond diagnostic applications, EVs are being explored as therapeutic agents in regenerative medicine and targeted drug delivery systems due to their natural biocompatibility and targeting capabilities [5].

Detailed Protocol: Ultracentrifugation-Based EV Isolation and RNA Profiling

Principle: This gold-standard method uses sequential centrifugation steps to isolate EVs based on size and density, followed by RNA extraction for downstream molecular analysis.

Workflow:

- Sample Collection and Pre-processing:

- Collect 10-20 mL blood in EDTA tubes

- Process within 1 hour: centrifuge at 1,600 × g for 15 min to obtain platelet-poor plasma

- Transfer supernatant to new tube, centrifuge at 16,000 × g for 20 min to remove apoptotic bodies and cell debris

- Aliquot and store at -80°C if not processing immediately

EV Isolation by Ultracentrifugation:

- Thaw plasma samples on ice if frozen

- Filter through 0.22 μm syringe filter

- Ultracentrifuge at 100,000 × g for 70 min at 4°C (Type 70 Ti rotor)

- Discard supernatant, resuspend pellet in 10 mL PBS (filtered through 0.22 μm)

- Repeat ultracentrifugation at 100,000 × g for 70 min

- Resuspend final EV pellet in 100-200 μL PBS for immediate use or store at -80°C

EV Characterization:

- Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA): Dilute EV sample 1:1000 in PBS, measure size distribution and concentration (NanoSight NS300)

- Transmission Electron Microscopy: Fix EVs in 2% paraformaldehyde, adsorb to formvar-carbon coated grids, negative stain with 1% uranyl acetate, image at 80 kV

- Western Blot: Detect EV markers (CD63, CD81, CD9, TSG101) and absence of negative markers (calnexin, GM130)

RNA Extraction and Analysis:

- Extract RNA using miRNeasy Micro Kit or equivalent

- Assess RNA quality and quantity using Bioanalyzer RNA Pico Chip

- For small RNA sequencing:

- Library preparation using NEBNext Small RNA Library Prep Kit

- Size selection for 15-50 nt fragments

- Sequence on Illumina platform (single-end 75 bp)

- For qRT-PCR:

- Reverse transcription using TaqMan MicroRNA Reverse Transcription Kit

- Pre-amplification if necessary

- qPCR with EV RNA-specific assays

Quality Control:

- Minimize freeze-thaw cycles to preserve EV integrity

- Include vesicle-free PBS as negative control throughout isolation

- Monitor protein contamination using BCA assay (typical EV preparation: protein/particle ratio ~100-500 fg/particle)

- Validate RNA quality: RIN >7.0 for mRNA analysis

Figure 3: EV Isolation and RNA Analysis Workflow

Cell-Free RNA (cfRNA)

Core Characteristics and Biological Significance

Cell-free RNA (cfRNA) comprises diverse RNA species circulating in bodily fluids, first discovered in plasma and serum in 1972 [6]. cfRNAs exist in multiple forms, including messenger RNA (mRNA), microRNA (miRNA), long non-coding RNA (lncRNA), circular RNA (circRNA), piwi-interacting RNA (piRNA), and small nuclear RNA (snRNA) [6]. These molecules are protected from degradation by RNases through various mechanisms, including encapsulation within extracellular vesicles, association with lipoprotein complexes, or binding to RNA-binding proteins like argonaute 2 (AGO2) [6]. Unlike cfDNA, cfRNA provides dynamic information about gene expression patterns and regulatory processes occurring in tumor cells [6]. A significant advantage of cfRNA is its high tissue specificity, which helps overcome the tissue-of-origin limitation in ctDNA analysis [6]. Studies have shown that cfRNAs in blood are more sensitive than cfDNAs in disease detection, and researchers can identify the tissue source of cfRNAs through bioinformatics algorithms [6].

Current Detection Technologies and Methodologies

cfRNA analysis requires specialized approaches to address challenges related to its instability and low abundance in circulation.

Table 4: cfRNA Detection and Analysis Platforms

| RNA Type | Detection Methods | Sensitivity | Primary Applications | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mRNA | RNA-seq, qRT-PCR | Moderate | Gene expression profiling, fusion detection | Requires rapid processing, RNA stabilization |

| miRNA | miRNA-seq, qRT-PCR arrays | High | Diagnostic signatures, treatment monitoring | Stable in circulation, well-established protocols |

| lncRNA | RNA-seq, targeted panels | Variable | Cancer subtyping, prognostic stratification | Lower abundance, specific assay design |

| circRNA | RNase R treatment + RNA-seq, ddPCR | High | Drug resistance monitoring, stable biomarkers | Resistance to exonuclease degradation |

| piRNA | Small RNA-seq | Low | Germ cell tumors, emerging biomarkers | Limited knowledge of functions |

Applications in Cancer Monitoring and Research

cfRNA biomarkers demonstrate significant utility across multiple cancer applications. For early cancer detection, specific cfRNA signatures enable non-invasive identification of tumors. For instance, the SNORD3B-1 5' region with secondary structure demonstrates stable existence in plasma, with abundance serving as a biomarker for early diagnosis of liver cancer [6]. The S domain of srpRNA RN7SL1 shows reliable performance in hepatocellular carcinoma diagnosis and prognosis [6]. In therapy resistance monitoring, circRNAs have emerged as particularly valuable biomarkers due to their exceptional stability from covalently closed-loop structures [7]. Specific circRNAs including circHIPK3, circFOXO3, and circRNA100290 modulate cancer pathways and affect chemotherapy sensitivity [7]. For example, circRNA102231 is overexpressed in gefitinib-resistant NSCLC, functioning as a sponge for miR-130a-3p [7]. Similarly, circRNA CDR1as correlates with tamoxifen resistance in breast cancer through modulation of the miR-7/EGFR pathway [7]. Beyond oncology, cfRNA applications extend to prenatal screening, infectious diseases, and autoimmune disorders through analysis of expression patterns in plasma, saliva, urine, and other biofluids [6] [8].

Detailed Protocol: CircRNA Enrichment and Detection for Drug Resistance Monitoring

Principle: This protocol leverages circRNA resistance to exonuclease degradation to enrich for circular species, followed by precise quantification using droplet digital PCR for monitoring therapy resistance.

Workflow:

- Blood Collection and Plasma Separation:

- Collect 10 mL blood in PAXgene Blood RNA tubes

- Process within 4 hours: centrifuge at 1900 × g for 10 min at room temperature

- Transfer plasma to new tube, centrifuge at 16,000 × g for 10 min to remove debris

- Aliquot plasma and store at -80°C

RNA Extraction:

- Thaw plasma samples on ice

- Add 1 volume of Denaturing Solution (if needed for miRNA preservation)

- Extract total RNA using miRNeasy Serum/Plasma Kit

- Include MS2 bacteriophage RNA or synthetic spike-ins as extraction controls

- Elute in 14 μL nuclease-free water

- Quantify using Qubit RNA HS Assay

RNase R Treatment for CircRNA Enrichment:

- Set up reaction:

- 8 μL RNA extract

- 1 μL RNase R (20 U/μL)

- 1 μL 10× RNase R Reaction Buffer

- Incubate at 37°C for 15 min

- Purify using RNA Clean & Concentrator-5 kit

- Optional: Include no-RNase R control for comparison

- Set up reaction:

Reverse Transcription:

- Use SuperScript IV Reverse Transcriptase with random hexamers

- Include no-RT controls to assess DNA contamination

- Use circRNA-specific divergent primers for targeted reverse transcription

Droplet Digital PCR Quantification:

- Prepare reaction mix:

- 10 μL 2× ddPCR Supermix for Probes

- 1 μL 20× circRNA-specific assay (divergent primers/TaqMan probe)

- 4 μL cDNA template

- 5 μL nuclease-free water

- Generate droplets using QX200 Droplet Generator

- Perform PCR: 95°C for 10 min, then 40 cycles of 94°C for 30 s and 60°C for 60 s, 98°C for 10 min

- Read droplets using QX200 Droplet Reader

- Analyze using QuantaSoft software

- Prepare reaction mix:

Data Analysis:

- Calculate copies/μL based on Poisson distribution

- Normalize to spike-in controls or reference circRNAs

- Establish threshold for resistance detection based on clinical validation studies

Quality Control:

- RNA integrity: Assess using Bioanalyzer if sufficient material

- RNase R efficiency: Monitor by qPCR comparing linear vs. circular transcripts

- Limit of detection: Establish using synthetic circRNA standards

- Inter-assay variability: Include reference samples across runs

Figure 4: CircRNA Detection Workflow for Drug Resistance

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Table 5: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Circulating Biomarker Analysis

| Reagent/Platform | Supplier Examples | Primary Application | Key Features | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| cfDNA Blood Collection Tubes | Streck, PAXgene, Roche | ctDNA stabilization | Preserves cfDNA for up to 7 days at room temperature | Compatibility with downstream assays |

| CTC Enrichment Kits | Menarini Silicon Biosystems, Miltenyi Biotec | CTC isolation | EpCAM-based or marker-independent | Cell viability preservation |

| EV Isolation Kits | System Biosciences, Thermo Fisher | EV purification | Polymer-based precipitation, antibody-based | Co-precipitation of contaminants |

| RNA Stabilization Reagents | Qiagen, Zymo Research | cfRNA preservation | RNase inhibition, RNA integrity maintenance | Compatibility with extraction methods |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers | Integrated DNA Technologies | NGS library preparation | Error correction, quantitative accuracy | Increased sequencing complexity |

| Digital PCR Systems | Bio-Rad, Thermo Fisher | Absolute quantification | High sensitivity, no standard curves | Limited multiplexing capability |

| Next-Generation Sequencers | Illumina, Pacific Biosciences | Comprehensive profiling | High throughput, multi-analyte capability | Bioinformatics infrastructure needs |

| Microfluidic Platforms | Fluxion Biosciences, BioFluidica | CTC/EV isolation | Integrated processing, automation | Throughput limitations |

Comparative Analysis and Integration Strategies

Table 6: Integrated Comparison of Circulating Biomarkers in Liquid Biopsy

| Parameter | ctDNA | CTCs | Extracellular Vesicles | cfRNA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Analytical Sensitivity | 0.01% VAF (targeted), <0.001% (SV-based) | 1-10 CTCs/mL blood | ~10 EV particles (dPCR) | Variable (miRNA: high, mRNA: moderate) |

| Tumor Representation | Tumor heterogeneity (via fragmentation) | Single-cell resolution, viable cells | Molecular cargo from parent cells | Active gene expression patterns |

| Stability in Circulation | Short half-life (minutes-hours) | Fragile, limited viability | High stability | Protected forms (EVs, protein complexes) |

| Information Content | Genetic and epigenetic alterations | Genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, functional | Proteins, lipids, nucleic acids | Expression profiling, regulatory networks |

| Technical Challenges | Low abundance in early-stage, standardization | Extreme rarity, heterogeneity | Isolation purity, standardization | Instability, low abundance |

| Clinical Readiness | Advanced (FDA-approved assays) | Moderate (CellSearch approved) | Emerging (academic and commercial) | Emerging (growing validation) |

| Ideal Applications | MRD, therapy monitoring, resistance mutations | Prognostic stratification, functional studies, metastasis research | Early detection, subtyping, drug delivery | Therapy response, resistance mechanisms |

| Complementary Approach | Combined with fragmentomics | Combined with single-cell omics | Combined with cargo analysis | Combined with epigenetic profiling |

The future of liquid biopsy lies in integrated multi-analyte approaches that combine the strengths of different circulating biomarkers. Simultaneous analysis of ctDNA, CTCs, EVs, and cfRNA from a single blood sample provides complementary information that offers a more comprehensive understanding of tumor biology than any single analyte alone [2]. For instance, combining ctDNA mutation analysis with CTC functional characterization and EV RNA profiling can provide insights into genetic alterations, cellular phenotypes, and intercellular communication simultaneously. Such integrated approaches are particularly valuable for addressing tumor heterogeneity, monitoring evolving resistance mechanisms, and developing personalized treatment strategies based on a holistic view of the tumor ecosystem.

{=>}

The Biology of Tumor Shedding: Origins, Half-Life, and Dynamics in Circulation

Tumor shedding, the process by which cancerous lesions release cellular material into the circulation, is the fundamental biological principle underpinning liquid biopsy. The analysis of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) and circulating tumor cells (CTCs) has emerged as a powerful, non-invasive approach for cancer monitoring, profiling, and detecting minimal residual disease [2] [9]. The utility of these analytes is dictated by their biology: their origins, the mechanisms of their release, their quantity in circulation, and their rapid clearance. A deep understanding of these dynamics is crucial for researchers and drug development professionals to accurately interpret liquid biopsy data, design effective clinical studies, and develop robust predictive biomarkers. This application note synthesizes current knowledge on the biology of tumor shedding, providing structured quantitative data, experimental protocols, and visual frameworks to guide research in this rapidly advancing field.

Core Biological Principles and Quantitative Parameters

The presence and concentration of tumor-derived material in the blood are governed by a set of biological processes and kinetic parameters. Key release mechanisms include apoptosis, necrosis, and active secretion, while the analyte half-life determines the time window for which it reflects the current tumor state [10]. The following sections and tables summarize the critical quantitative data and biological characteristics of ctDNA and CTCs.

Table 1: Characteristics and Release Mechanisms of Circulating Tumor Nucleic Acids and Cells

| Analyte | Primary Release Mechanisms | Typical Fragment Size/Characteristics | Key Release-Associated Proteins/Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Circulating Tumor DNA (ctDNA) | Apoptosis: Major source. Produces short, nucleosome-bound fragments [10].Necrosis: Results in longer, more random DNA fragments [10].Active secretion via extracellular vesicles (less characterized) [10]. | ~167 bp (DNA wrapped around one nucleosome plus linker), showing a ladder-like pattern on gel electrophoresis [10]. | Caspase-activated DNase (CAD) and other nucleases execute DNA fragmentation during apoptosis [10]. ERp5 protein identified as critical for shedding cell surface proteins like MICA, a potential model for other release mechanisms [11]. |

| Circulating Tumor Cells (CTCs) | Active invasion and intravasation into vasculature [12].Passive release from tumor margins, potentially enhanced by macrovascular infiltration in advanced disease [13]. | Whole, viable cells. Can circulate as single cells or clusters (homotypic or heterotypic with immune cells); clusters are associated with enhanced metastatic potential and can spike near end-of-life [13]. | EpCAM (used for CellSearch enrichment), Vimentin, N-cadherin [9]. |

Table 2: Kinetic and Quantitative Parameters of ctDNA and CTCs

| Parameter | ctDNA | CTCs |

|---|---|---|

| Half-Life in Circulation | ~16 minutes to several hours [2]. | ~1 to 2.5 hours [9]. |

| Represents | A snapshot of tumor cell death [2]. | A snapshot of viable, invasive cells [12]. |

| Shedding Probability (Modeled) | In lung cancer, ~0.014% of a tumor cell's DNA is shed per cell death (qd ≈ 1.4 × 10⁻⁴ haploid genome equivalents per cell death) [14]. | Not quantitatively modeled in the same way; release is stochastic and dynamic [12]. |

| Typical Abundance in Blood | Can range from <0.1% of total cell-free DNA in early-stage cancer to >90% in advanced disease [2]. | Extremely rare; approximately 1 CTC per 1-10 million leukocytes [9]. |

| Key Dynamic Behaviors | Levels correlate with tumor burden and cell turnover; rapid clearance allows for real-time monitoring of treatment response [2]. | Counts do not always correlate with primary tumor size; can show significant temporal fluctuations and perimortem spikes in clusters [12] [13]. |

Diagram 1: The Lifecycle of Tumor-Derived Analytes. This pathway outlines the journey of ctDNA and CTCs from their origin in the tumor, through their release into circulation, to their eventual clearance.

Experimental Protocols for Analyzing Shedding Dynamics

Robust experimental protocols are essential for investigating the dynamics of tumor shedding. Below are detailed methodologies for quantifying ctDNA shedding levels and for monitoring CTCs in vivo, which are critical for preclinical research.

Protocol: Quantifying Lesion-Specific ctDNA Shedding Using the Lesion Shedding Model (LSM)

The LSM is a computational framework that uses sequencing data from multiple lesions and a liquid biopsy to order lesions by their relative ctDNA shedding levels, helping to identify aggressively shedding lesions [15].

1. Sample Preparation and Input:

- Tissue Samples: Obtain whole-exome or genome sequencing (WES/WGS) data from multiple synchronous tumor lesions. Ensure high tumor purity; lesions with poor purity should be excluded [15].

- Liquid Biopsy: Sequence at least one blood plasma cfDNA sample collected most proximally to the lesion biopsies. Data should be formatted into a MAF (Mutation Annotation Format) file containing alteration information, including Variant Allele Frequency (VAF) or Cancer Cell Fraction (CCF) [15].

2. Hypothesis Blood Generation:

- For a given patient, subsample k lesions out of the total n lesions for computational tractability and to model missing lesions.

- For the selected k lesions, generate a "hypothesis blood" (HB) cfDNA profile. This is a mathematical mixture of the alterations from the k lesions, weighted by a hypothesis vector W = (w₁, w₂, ..., wₖ), where w represents the hypothesized relative shedding level for each lesion [15].

3. Target Function Optimization:

- Define a target function (a family of functions F) that measures the goodness-of-fit between the generated hypothesis blood (HB) and the actual observed cfDNA profile.

- Iteratively search for the optimal hypothesis vector W that minimizes the target function, thereby identifying the shedding levels that best explain the actual ctDNA data [15].

4. Consensus Shedding Network:

- Repeat the subsampling and optimization process many times (e.g., 1000 iterations) to ensure robustness.

- Aggregate the top hypothesis vectors from all iterations to calculate a consensus partial ordering of lesions from strongest to poorest shedders and construct a relative shedding level graph [15].

Key Application: This model is particularly useful for understanding which lesions contribute most to the ctDNA pool, which may have implications for targeting lesions responsible for progression or therapeutic resistance [15].

Protocol: In Vivo Monitoring of Circulating Tumor Cell Dynamics

Real-time monitoring of CTCs provides insights into their dynamic and fluctuating release, which is missed by single-time-point blood draws [12].

1. Animal Model Preparation:

- Inoculate immunodeficient mice with human tumor cell lines, preferably expressing fluorescent reporters (e.g., GFP) or luciferase for validation. Orthotopic inoculation (e.g., into the mammary gland for breast cancer) is preferred for modeling the native tumor microenvironment [12].

2. In Vivo Flow Cytometry Setup:

- Photoacoustic Flow Cytometry (PAFC): For detecting intrinsically pigmented cells (e.g., melanoma CTCs). Use a safe laser energy level (e.g., wavelength 1064 nm) focused on a peripheral blood vessel (e.g., mouse ear vessel, 50-250 µm diameter) [12].

- Fluorescence Flow Cytometry (FFC): For detecting fluorescently labeled cells. Use a continuous-wave laser (e.g., 488 nm for GFP) focused on the vessel. Set an amplitude threshold for positive signals (typically mean + 5 standard deviations of the autofluorescence background) [12].

3. Data Acquisition and Continuous Monitoring:

- Anesthetize the mouse and position it to allow stable laser alignment on the target blood vessel.

- Monitor the signal for extended periods (e.g., 60 minutes). Record the timestamp of every signal peak that crosses the set threshold, corresponding to a CTC or CTC cluster passing the detection point [12].

4. Data Analysis:

- CTC Rate Calculation: Divide the total monitoring time into short, consecutive intervals (e.g., 5 minutes). Calculate the CTC rate (cells per 5 min) for each interval to visualize dynamic fluctuations.

- Temporal Dynamics: Plot the CTC rate over time and correlate with primary tumor size measurements (e.g., caliper) and metastasis development (via bioluminescence imaging) at different time points (e.g., weekly) [12].

Key Finding: This protocol typically reveals that CTC counts are highly variable over time and do not always correlate with primary tumor size, with peaks often occurring during early disease stages [12].

Diagram 2: In Vivo CTC Monitoring Workflow. This protocol visualizes the steps for real-time, continuous monitoring of CTC dynamics in a preclinical model, revealing transient fluctuations.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Tumor Shedding Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Specific Examples/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| CellSearch System | FDA-cleared method for enumerating CTCs from human blood samples. Uses immunomagnetic enrichment based on EpCAM expression [9]. | Standardized for prognostic use in metastatic breast, colorectal, and prostate cancer. Critical for validating novel CTC detection methods [9]. |

| dPCR (digital PCR) | Absolute quantification of mutant allele frequencies in ctDNA without the need for standard curves. High sensitivity for tracking specific mutations [2]. | Ideal for tumor-informed monitoring of known mutations (e.g., in KRAS, EGFR, PIK3CA). Platforms include droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) [2]. |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) Panels | Comprehensive profiling of multiple genes and mutations from ctDNA. Allows for tumor-uninformed analysis and assessment of heterogeneity [2]. | Targeted panels (e.g., CAPP-Seq, TEC-Seq) offer deep sequencing for high sensitivity. Error-correction methods (e.g., Unique Molecular Identifiers - UMIs) are essential for low-frequency variant calling [2]. |

| Fluorescent Reporter Cell Lines | Enables tracking of tumor cells in vitro and in vivo. Essential for protocols involving in vivo flow cytometry and metastasis validation [12]. | Common reporters: GFP (for FFC), luciferase (for bioluminescence imaging of metastases). Allows for isolation and functional study of CTCs [12]. |

| Antibodies for Surface Marker Enrichment | Isolation and characterization of CTCs and CTC clusters based on cell surface antigen expression. | EpCAM: Common epithelial marker [9].CD44, CD24: Used for identifying cancer stem cell (CSC) subpopulations within CTCs [12]. |

| Nuclease Inhibitors | Preserve the integrity of cell-free nucleic acids in blood collection tubes by inhibiting DNases and RNases. | Critical for pre-analytical sample stabilization. Should be added to blood collection tubes or plasma processing reagents immediately after draw [10]. |

The biology of tumor shedding is complex, dynamic, and central to the application of liquid biopsy. Key characteristics such as the distinct origins and short half-lives of ctDNA and CTCs make them powerful, real-time biomarkers. However, challenges remain, including understanding the biological drivers of differential shedding between lesions and the clinical significance of transient CTC dynamics. As research continues to unravel these secrets, the integration of sophisticated mathematical models like the LSM and advanced detection protocols will be crucial for translating the biology of tumor shedding into improved cancer monitoring and drug development strategies.

Liquid biopsy represents a transformative approach in oncology, enabling the detection and analysis of cancer-derived biomarkers from bodily fluids such as blood, urine, or cerebrospinal fluid [16]. Unlike traditional tissue biopsies, which require invasive surgical procedures and provide only a static snapshot of a dynamic disease, liquid biopsy offers a minimally invasive, repeatable method for tracking cancer progression, detecting early-stage cancers, and monitoring therapeutic responses [17]. This technique primarily focuses on analyzing circulating tumor cells (CTCs), circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA), and other cancer-derived genetic materials that provide critical information on tumor heterogeneity, mutation profiles, and emerging drug resistance [9] [16].

The clinical significance of liquid biopsy is particularly evident in its ability to address fundamental limitations of tissue biopsy. Tissue biopsies are invasive, often limited to a single point in space and time, challenging to repeat, and may fail to reflect the full spectrum of tumor heterogeneity due to sampling bias [17]. In contrast, liquid biopsy captures contributions from multiple tumor sites—including primary and metastatic lesions—providing a more comprehensive molecular profile of the patient's disease [18] [19]. This capability is crucial for guiding personalized treatment strategies in advanced cancers where tumor heterogeneity significantly impacts therapeutic outcomes [20].

Key Advantages of Liquid Biopsy

Non-Invasiveness and Clinical Practicality

The minimally invasive nature of liquid biopsy, typically requiring only a blood draw, translates to substantial clinical benefits over conventional tissue biopsies [21]. This characteristic eliminates procedural risks associated with surgical biopsies, reduces patient discomfort, and enables higher compliance for repeated sampling, which is essential for longitudinal disease monitoring [22]. The simplicity of sample collection facilitates integration into routine clinical workflows, potentially allowing for decentralized testing through local phlebotomy services rather than specialized surgical facilities [17].

From a healthcare systems perspective, the non-invasive nature of liquid biopsy may lead to reduced costs associated with invasive procedures, hospital stays, and management of procedure-related complications [17]. Furthermore, the ability to obtain serial samples enables clinicians to monitor disease progression and treatment response more frequently, potentially identifying treatment failure or disease recurrence earlier than standard imaging modalities [9] [22].

Real-Time Monitoring and Dynamic Assessment

Liquid biopsy enables real-time tracking of tumor evolution, providing clinicians with dynamic information about treatment response and emerging resistance mechanisms [7] [16]. Unlike tissue biopsies, which offer a historical snapshot of the tumor genome at a single time point, liquid biopsy reflects the current molecular status of the disease, allowing for timely treatment adjustments [17].

The dynamic monitoring capability of liquid biopsy is particularly valuable for assessing minimal residual disease (MRD) after curative-intent therapy and detecting early recurrence before clinical or radiographic manifestation [16] [22]. Studies in triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) have demonstrated that changes in CTC counts during systemic therapy can predict treatment response, with reductions in CTC levels correlating with improved progression-free survival [22]. Similarly, monitoring ctDNA levels can provide early evidence of therapeutic efficacy, often weeks to months before traditional imaging methods can detect changes in tumor burden [9] [21].

Comprehensive Capture of Tumor Heterogeneity

Tumor heterogeneity—encompassing genetic, epigenetic, and phenotypic diversity among cancer cells—represents a significant challenge in cancer treatment, contributing to mixed therapeutic responses and drug resistance [18] [19]. Liquid biopsy effectively addresses this challenge by capturing tumor-derived material released from multiple metastatic sites simultaneously, providing an integrated representation of the tumor's molecular landscape [18] [17].

Research comparing liquid biopsy with multi-region tissue sampling has demonstrated that liquid biopsy can detect spatial heterogeneity that might be missed by a single tissue biopsy [18]. A study analyzing 56 postmortem tissue samples from eight cancer patients found that liquid biopsy identified mutations across different metastatic sites, with overlapping mutation profiles between liquid and tissue biopsies ranging from 33% to 92% [18]. This comprehensive sampling is particularly important for identifying resistance mutations that may emerge in distinct tumor subclones under selective pressure of targeted therapies [7] [19].

Quantitative Comparison: Liquid Biopsy vs. Tissue Biopsy

Table 1: Comparative analysis of key performance metrics between liquid biopsy and tissue biopsy

| Parameter | Liquid Biopsy | Tissue Biopsy | Clinical Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Invasiveness | Minimally invasive (blood draw) [21] [16] | Invasive surgical procedure [17] [20] | Reduced procedural risks; improved patient compliance [22] |

| Sampling Frequency | High (repeatable at multiple timepoints) [9] [19] | Limited (difficult to repeat) [17] | Enables dynamic monitoring of treatment response [7] |

| Tumor Representation | Captures contributions from multiple tumor sites [18] [17] | Limited to sampled region [18] [19] | Better representation of heterogeneity [18] |

| Turnaround Time | Potentially faster (e.g., 3+ weeks earlier than tissue) [17] | Longer (requires surgical scheduling and processing) [20] | Earlier treatment decisions [17] |

| Detection of Resistance Mutations | Can identify emerging resistance mutations during treatment [7] [18] | May miss resistance mutations in unsampled regions [18] [19] | More adaptive treatment strategies [7] |

Table 2: Clinical performance of liquid biopsy in capturing tumor heterogeneity based on the study by Dissecting Tumor Heterogeneity by Liquid Biopsy [18]

| Patient | Total Mutations Detected in Tissue | Mutations Detected in Liquid Biopsy | Overlap Rate | Mutations Exclusive to Liquid Biopsy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient 1 | 8 | 7 | 75% | 2 |

| Patient 2 | 7 | 6 | 67% | 2 |

| Patient 3 | 4 | 5 | 80% | 2 |

| Patient 4 | 12 | 11 | 58% | 6 |

| Patient 5 | 10 | 9 | 60% | 4 |

| Patient 6 | 5 | 4 | 80% | 0 |

| Patient 7 | 6 | 7 | 67% | 2 |

| Overall | 52 | 49 | 69% (average) | 18 (35% of total) |

Liquid Biopsy Biomarkers and Their Clinical Applications

Circulating Tumor Cells (CTCs)

CTCs are cancer cells shed from primary or metastatic tumors into the bloodstream [9] [22]. These cells provide a comprehensive molecular resource as they contain intact DNA, RNA, proteins, and metabolites that reflect the tumor's biological state [21]. The detection and enumeration of CTCs have established prognostic value in multiple cancers, with higher counts correlating with reduced progression-free and overall survival [9] [22].

In breast cancer, particularly TNBC, the presence of ≥5 CTCs per 7.5 mL of blood is associated with significantly worse outcomes, and changes in CTC counts during treatment can predict therapeutic response [22]. Modern CTC isolation technologies, such as the Parsortix system and the CellSearch method (the only FDA-cleared system for CTC enumeration), enable not only counting but also molecular characterization of these cells through downstream analyses like immunofluorescence, FISH, and next-generation sequencing [9] [17].

Circulating Tumor DNA (ctDNA)

ctDNA consists of short DNA fragments (approximately 20-50 base pairs) released into the circulation through apoptosis or necrosis of tumor cells [9] [21]. Although ctDNA typically represents only 0.1-1.0% of total cell-free DNA, its short half-life (approximately 1-2.5 hours) makes it an excellent biomarker for real-time assessment of tumor burden [9].

The clinical utility of ctDNA includes detection of actionable mutations, monitoring of treatment response, identification of emerging resistance mechanisms, and assessment of MRD [9] [16]. In colorectal cancer, monitoring specific mutations (APC, KRAS, TP53, PIK3CA) in ctDNA has been shown to correlate with tumor burden and CEA concentration during therapy [9]. Additionally, ctDNA testing can capture the complete mutational landscape of heterogeneous tumors, overcoming the sampling bias inherent in single-site tissue biopsies [18] [21].

Novel Biomarkers: Circular RNAs and Extracellular Vesicles

Beyond CTCs and ctDNA, liquid biopsy encompasses several emerging biomarkers with significant clinical potential. Circular RNAs (circRNAs) represent a class of stable non-coding RNAs characterized by covalently closed-loop structures that confer resistance to exonuclease degradation [7]. Their remarkable stability in body fluids and association with drug resistance mechanisms—such as miRNA sponging, regulation of apoptosis, and epithelial-mesenchymal transition—make them promising biomarkers for therapeutic monitoring [7].

Extracellular vesicles (EVs), including exosomes, are membrane-bound particles released by cells that contain proteins, nucleic acids, and lipids reflective of their cell of origin [9] [21]. These vesicles play important roles in intercellular communication and tumor microenvironment modulation, carrying tumor-specific molecules that can be exploited for diagnostic and monitoring purposes [9].

Experimental Protocols for Liquid Biopsy Analysis

Protocol for CTC Isolation and Analysis Using the Parsortix System

Principle: CTCs are isolated based on their larger size and deformability compared to blood cells using a microfluidic mechanism [17].

Reagents and Equipment:

- EDTA or citrate blood collection tubes

- Parsortix system (ANGLE plc)

- Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)

- Fixation buffer (4% formaldehyde)

- Permeabilization buffer (0.1% Triton X-100)

- Antibodies for immunofluorescence (e.g., anti-CK, anti-CD45)

- DAPI staining solution

- Microscope slides and mounting medium

Procedure:

- Collect 10-20 mL of peripheral blood into EDTA or citrate tubes.

- Process blood within 4-8 hours of collection; store at room temperature.

- Load blood sample into Parsortix instrument and run the separation program.

- Harvest captured cells onto a glass slide using the instrument's retrieval mechanism.

- Fix cells with 4% formaldehyde for 15 minutes at room temperature.

- Permeabilize with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 10 minutes if intracellular staining is required.

- Perform immunofluorescence staining using cytokeratin antibodies (epithelial marker) and CD45 antibodies (leukocyte marker) with DAPI for nuclear staining.

- Image slides using a fluorescence microscope and enumerate CTCs (CK+/CD45-/DAPI+).

- For molecular analysis, harvest cells into lysis buffer for nucleic acid extraction.

Downstream Applications:

- CTC enumeration for prognostic assessment

- Immunofluorescence for protein expression analysis

- Fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) for gene amplification detection

- Next-generation sequencing for mutation profiling

- Gene expression analysis using RT-PCR [17]

Protocol for ctDNA Analysis Using Next-Generation Sequencing

Principle: ctDNA is extracted from plasma and sequenced to identify tumor-specific mutations, with specialized methods to detect low variant allele frequencies [18].

Reagents and Equipment:

- Streck Cell-Free DNA Blood Collection Tubes or similar

- Plasma preparation tubes (EDTA)

- Centrifuge capable of 1600-3000 × g

- Commercial cfDNA extraction kit (e.g., QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid Kit)

- DNA quantification system (e.g., Qubit fluorometer)

- Library preparation kit for NGS

- Target enrichment system (hybridization-based or PCR-based)

- Next-generation sequencer

- Bioinformatics pipeline for variant calling

Procedure:

- Collect blood in cell-free DNA stabilization tubes (e.g., Streck tubes) to prevent genomic DNA contamination.

- Process samples within 6 hours of collection; centrifuge at 1600-3000 × g for 20 minutes to separate plasma.

- Transfer plasma to a fresh tube without disturbing the buffy coat and perform a second centrifugation at 16,000 × g for 10 minutes to remove remaining cells.

- Extract cfDNA using a commercial kit according to manufacturer's instructions.

- Quantify cfDNA using fluorometric methods; expect yields of 5-50 ng/mL plasma.

- Prepare sequencing libraries using protocols optimized for low-input DNA.

- Enrich for target regions (e.g., cancer gene panels) using hybridization capture or multiplex PCR.

- Sequence on an appropriate NGS platform with sufficient depth (typically >10,000x coverage).

- Analyze sequencing data using a bioinformatics pipeline designed for low-frequency variant detection.

Quality Control Considerations:

- Monitor fragment size distribution (ctDNA typically 160-180 bp)

- Include control samples to assess background error rates

- Set appropriate variant allele frequency thresholds (typically 0.1-0.5%)

- Filter out potential artifacts using duplicate removal and molecular barcode strategies [18]

Protocol for circRNA Detection from Plasma

Principle: circRNAs are isolated from plasma or exosomes and detected using reverse transcription-PCR or RNA sequencing with methods specific to their back-spliced junctions [7].

Reagents and Equipment:

- EDTA blood collection tubes

- RNase-free reagents and plasticware

- Centrifuge capable of 16,000 × g

- Total RNA extraction kit

- RNase R treatment (3-5 U/μg RNA)

- Reverse transcription kit

- PCR reagents or digital PCR system

- RNA sequencing library preparation kit

Procedure:

- Collect blood in EDTA tubes and process within 2 hours.

- Centrifuge at 1600-3000 × g for 20 minutes to separate plasma.

- Transfer plasma to a fresh tube and centrifuge at 16,000 × g for 10 minutes to remove vesicles and debris.

- Extract total RNA using a commercial kit with modifications for small RNAs.

- Treat RNA with RNase R (3-5 U/μg RNA) for 30 minutes at 37°C to degrade linear RNAs while preserving circRNAs.

- Perform reverse transcription using random hexamers or gene-specific primers.

- Detect circRNAs using:

- qRT-PCR: Design divergent primers that amplify across the back-splice junction

- Digital PCR: For absolute quantification of specific circRNAs

- RNA Sequencing: Prepare libraries from RNase R-treated RNA and sequence; identify circRNAs through back-splice junction detection algorithms

- Validate circRNA identity by Sanger sequencing of PCR products.

Applications:

- Detection of circRNAs associated with drug resistance (e.g., circHIPK3, circFOXO3)

- Monitoring of circRNA expression changes during therapy

- Correlation with treatment response and survival outcomes [7]

Visualizing Liquid Biopsy Workflows and Tumor Heterogeneity Capture

Diagram 1: Comprehensive workflow for liquid biopsy analysis from sample collection to clinical application

Diagram 2: Liquid biopsy captures comprehensive tumor heterogeneity compared to limited tissue sampling

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key research reagent solutions for liquid biopsy applications

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell-Free DNA Blood Collection Tubes (e.g., Streck, PAXgene) | Stabilizes nucleated blood cells to prevent genomic DNA contamination | ctDNA analysis, especially when delayed processing is anticipated | Maintains sample integrity for up to 7 days at room temperature [18] |

| CTC Enrichment Systems (e.g., Parsortix, CellSearch) | Isolate rare circulating tumor cells from blood | CTC enumeration, molecular characterization, functional studies | Choice between epitope-dependent (CellSearch) and size-based (Parsortix) methods [9] [17] |

| RNase R | Degrades linear RNAs while preserving circular RNAs | circRNA detection and analysis from plasma or exosomes | Treatment conditions must be optimized for different sample types [7] |

| Next-Generation Sequencing Kits | Library preparation and target enrichment for mutation detection | ctDNA sequencing, CTC whole genome/transcriptome analysis | Ultra-sensitive protocols required for low VAF detection (0.1% or lower) [18] |

| Digital PCR Assays | Absolute quantification of rare mutations | Validation of NGS findings, monitoring specific mutations | Higher sensitivity than qPCR for rare variant detection [7] |

| Exosome Isolation Kits (e.g., precipitation, immunoaffinity-based) | Isolation of extracellular vesicles from biofluids | Exosomal RNA/protein analysis, biomarker discovery | Different methods yield exosomes with varying purity and recovery [9] |

Liquid biopsy represents a paradigm shift in cancer management, offering distinct advantages over traditional tissue biopsy through its non-invasive nature, capacity for real-time monitoring, and comprehensive capture of tumor heterogeneity. The integration of multiple analyte approaches—combining CTCs, ctDNA, and novel biomarkers like circRNAs—provides complementary molecular information that enhances our understanding of tumor dynamics and evolution [17] [20].

As liquid biopsy technologies continue to advance with improvements in sensitivity, standardization, and bioinformatics analysis, their role in clinical oncology is expected to expand significantly. Future applications may include population-based cancer screening, ultra-sensitive residual disease detection, and longitudinal adaptation of therapy based on evolving molecular profiles [7] [17]. The ongoing development of standardized protocols and analytical frameworks will be essential for realizing the full potential of liquid biopsy in precision oncology and improving outcomes for cancer patients across the disease spectrum.

Liquid biopsy is transforming oncology by providing a minimally invasive window into tumor biology. While blood plasma is the most common source, biofluids in closer anatomical proximity to tumors often contain higher concentrations of tumor-derived material, offering enhanced sensitivity for detecting cancer biomarkers [23] [24]. These "local" liquid biopsy sources—including urine, saliva, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and pleural effusions—enable more precise genomic analysis, early detection, and therapy monitoring while overcoming limitations of traditional tissue biopsies [25] [26]. The selection of an appropriate biofluid is critical and depends on the tumor location, the biomarker of interest, and the specific clinical application, ranging from early detection to monitoring minimal residual disease (MRD) [27]. This article provides a detailed overview of the applications, performance metrics, and standardized protocols for utilizing these alternative biofluids in cancer research and drug development.

The table below summarizes the key characteristics, dominant biomarkers, and clinical applications of the four primary non-blood biofluids.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Non-Blood Biofluid Sources for Liquid Biopsy

| Biofluid | Primary Cancer Applications | Key Biomarkers | Advantages | Limitations & Pre-analytical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urine | Urological (Bladder, Prostate, Renal), also non-urological [24] | ctDNA, cfRNA, EVs [27] [28] | Fully non-invasive collection; Ideal for high-compliance repeated sampling; Low biological risk [24]. | Subject to variable dilution; Requires rapid stabilization to prevent enzymatic degradation of biomarkers; First-void urine often has highest biomarker concentration [23] [24]. |

| Saliva | Oral, Head and Neck, Lung, Pancreatic [29] [30] | Salivary cfDNA (ScfDNA), miRNAs, Proteins, EVs [23] [30] | 85% accuracy for non-oral cancers per meta-analysis [29]; Extremely low-cost and simple collection [29] [30]. | Rapid protein degradation requires additives; Composition varies with stimulation method; Contamination from oral microbes and food particles [29] [30]. |

| Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) | Brain Tumors, Leptomeningeal Carcinomatosis [23] [26] | ctDNA, CTCs [23] | Direct window to CNS; High tumor DNA fraction despite low total volume; Critical for assessing intrathecal therapy [23] [24]. | Invasive collection via lumbar puncture; Low total volume and biomarker concentration demands highly sensitive assays [23]. |

| Pleural Effusion | Lung, Breast, Thoracic Cancers [25] [26] | ctDNA, CTCs, miRNAs, EVs [25] | Very high ctDNA concentration & mutant allelic fraction; Outperforms plasma and cell blocks in genotyping sensitivity; Useful for targeted therapy selection [25] [26]. | Requires diagnostic thoracentesis; Distinguishing malignant from benign effusion is crucial; Sample processing must include centrifugation to remove cells and debris [25]. |

Biofluid-Specific Experimental Protocols

Urine Collection and cfDNA Analysis for Urological Cancers

Application: Non-invasive detection of TERT promoter mutations in bladder cancer [24].

Protocol:

- Collection: Collect 50-100 mL of first-void morning urine into a sterile container with an appropriate preservative (e.g., EDTA, proprietary nucleic acid stabilizers) to prevent degradation [23].

- Processing: Centrifuge at 2,000 × g for 10 minutes to pellet cells. Transfer the supernatant to a fresh tube and centrifuge at 16,000 × g for 20 minutes to remove residual debris and vesicles.

- cfDNA Isolation: Extract cfDNA from the clarified supernatant using a silica-membrane or magnetic bead-based kit optimized for low-abundance DNA from urine. Elute in a low volume (e.g., 20-50 µL) of Tris-EDTA buffer.

- Mutation Detection:

- For known variants (e.g., TERT C228T): Use highly sensitive methods like Droplet Digital PCR (ddPCR). Prepare a reaction mix with fluorescent probes for wild-type and mutant alleles, generate droplets, and perform PCR. Analyze on a droplet reader to determine the mutant allele concentration (copies/µL) [27].

- For unknown variants or comprehensive profiling: Use Targeted Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS). Prepare libraries from isolated cfDNA using a panel targeting cancer-associated genes (e.g., Uro-Amplicon Panel). Sequence on a platform like Illumina MiSeq and analyze data with bioinformatics tools (e.g., GATK, VarScan) for variant calling [23].

Saliva Collection and Biomarker Analysis for Oral Cancer Screening

Application: Early detection and monitoring of Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma (OSCC) via multi-omics analysis [30] [28].

Protocol:

- Collection: Instruct donors not to eat, drink, or smoke for at least 90 minutes prior. Collect unstimulated whole saliva (5-10 mL) by passive drooling into a 50 mL conical tube placed on ice. For standardized collection, use the "Lashley Cup" for gland-specific saliva [30].

- Stabilization and Processing: Immediately add a protease inhibitor cocktail to the sample. Centrifuge at 2,600 × g for 15 minutes at 4°C to remove cells and debris. Aliquot the supernatant and store at -80°C.

- Biomarker Isolation and Analysis:

- DNA Methylation Analysis: Isolate salivary cell-free DNA (ScfDNA) using a commercial kit. Treat DNA with sodium bisulfite to convert unmethylated cytosines to uracils. Analyze using quantitative PCR (qPCR) or pyrosequencing for specific gene promoters (e.g., DAPK, MGMT) or employ a methylation-specific NGS panel [24] [28].

- miRNA Profiling: Extract total RNA, including small RNAs, from 200 µL of processed saliva. Synthesize cDNA and perform RT-qPCR using TaqMan assays for miRNAs of interest (e.g., miR-21, miR-184) [30]. For discovery, use miRNA sequencing.

- Proteomic Analysis: Concentrate proteins from saliva using centrifugal filters. Digest proteins with trypsin and analyze by LC-MS/MS (Liquid Chromatography with Tandem Mass Spectrometry) to identify and quantify cancer-associated proteins (e.g., CD44, IL-8) [31] [30].

Pleural Effusion Processing for ctDNA Genotyping in Lung Cancer

Application: Sensitive detection of EGFR mutations in cytology-negative Malignant Pleural Effusions (MPE) from NSCLC patients [25] [26].

Protocol:

- Collection: Collect pleural fluid during standard therapeutic thoracentesis in EDTA tubes to prevent clotting.

- Processing: Centrifuge the sample at 2,000 × g for 10 minutes to generate a cell pellet (for cytology/cell block) and cell-free supernatant. Transfer the supernatant to a new tube and perform a second, high-speed centrifugation at 16,000 × g for 20 minutes to remove any remaining cellular debris and platelets.

- cfDNA Isolation: Extract cfDNA from the double-centrifuged supernatant using a high-volume plasma cfDNA kit, given the typically high DNA yield. Quantify DNA using a fluorometer.

- Genotyping:

- For routine EGFR mutation testing: Use ddPCR with assays for common mutations (e.g., exon 19 deletions, L858R, T790M). This method offers high sensitivity and absolute quantification of mutant allelic frequency [27] [26].

- For comprehensive genomic profiling: Use NGS with a targeted amplicon-based lung cancer panel (e.g., covering EGFR, KRAS, ALK, etc.). Due to the high tumor fraction in MPE-cfDNA, NGS can reliably detect mutations and resistance mechanisms with high concordance to tissue [25] [26].

Diagram: Universal workflow for biofluid processing in liquid biopsy

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Kits for Biofluid Analysis

| Reagent/Kits | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| cfDNA Isolation Kits (e.g., QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid Kit) | Isolation of high-quality, short-fragment cfDNA from biofluid supernatants. | Critical for removing PCR inhibitors; Kits optimized for plasma are generally applicable to urine, CSF, and pleural fluid supernatants. |

| RNA Stabilization Reagents (e.g., RNAlater) | Preservation of RNA integrity in saliva and urine during collection and storage. | Prevents degradation of labile miRNA and other RNA species by RNases; must be added immediately after sample collection. |

| Droplet Digital PCR (ddPCR) Supermixes | Absolute quantification of low-abundance mutations (e.g., EGFR, TERT) without standard curves. | Offers superior sensitivity and precision for detecting rare mutants in a high background of wild-type DNA; ideal for urine and pleural fluid. |

| Targeted NGS Panels (e.g., Illumina TSO 500 ctDNA) | Comprehensive profiling of cancer-associated genes from low-input cfDNA. | Enables detection of single nucleotide variants, indels, and fusions; requires library preparation kits compatible with fragmented DNA. |

| Protease Inhibitor Cocktails | Inhibition of proteases in saliva to prevent protein biomarker degradation. | Essential additive during saliva collection to maintain the integrity of the proteome for subsequent MS or immunoassay analysis. |

| Bisulfite Conversion Kits (e.g., EZ DNA Methylation Kit) | Chemical treatment of DNA for methylation analysis, converting unmethylated C to U. | Key first step for analyzing DNA methylation biomarkers in salivary or urinary cfDNA via PCR or NGS. |

Urine, saliva, CSF, and pleural effusions are powerful biofluid sources that complement and, in some contexts, surpass blood-based liquid biopsies. Their proximity to the tumor site results in higher biomarker concentrations, enabling more sensitive detection of driver mutations, therapy-resistant clones, and minimal residual disease [24] [26]. The ongoing standardization of collection protocols and analytical methods, as outlined in this article, is crucial for integrating these biofluids into robust and reproducible research workflows and clinical trials. As multi-omics approaches and sequencing technologies continue to advance, the strategic use of these localized liquid biopsies will undoubtedly accelerate the development of personalized cancer diagnostics and therapeutics.

Methodologies and Clinical Translation: From Isolation Technologies to Oncology Applications

Liquid biopsy has emerged as a transformative approach in oncology, enabling non-invasive cancer detection, prognosis, and therapy monitoring through the analysis of tumor-derived biomarkers in bodily fluids. Among these biomarkers, circulating tumor cells (CTCs) provide a complete molecular profile of the tumor, including DNA, RNA, and protein information [9]. However, CTCs are exceptionally rare, with approximately 1-10 CTCs present among millions of white blood cells and billions of red blood cells in just 1 milliliter of blood [32]. This extreme rarity presents a significant technological challenge, making efficient isolation and enrichment the critical first step for any subsequent analysis.

This Application Note provides a detailed technical overview of three principal methodologies for CTC isolation and enrichment: immunomagnetic capture, microfluidics, and size-based filtration. We focus on practical protocols, performance metrics, and reagent solutions to support researchers in implementing these techniques within the broader context of liquid biopsy for cancer monitoring.

Technical Comparison of Core Technologies

The table below summarizes the fundamental principles, advantages, and limitations of the three primary CTC isolation techniques.

Table 1: Comparison of Core CTC Isolation and Enrichment Techniques

| Technique | Fundamental Principle | Key Advantages | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Immunomagnetic Capture | Uses antibody-coated magnetic beads targeting surface antigens (e.g., EpCAM) on CTCs [32]. | High purity and specificity; amenability to automation (e.g., CellSearch system) [32] [9]. | Bias towards CTCs expressing the target antigen; potential loss of phenotypically heterogeneous or EpCAM-low CTCs [32]. |

| Microfluidics | Leverages microscale fluid dynamics and device structures to separate CTCs based on physical or affinity properties [33]. | High recovery rates and cell viability; low reagent consumption; integration with downstream analysis [33]. | Throughput limitations for processing large blood volumes; potential for channel clogging [34] [33]. |

| Size-Based Filtration | Separates CTCs from smaller hematological cells using physical filters with precise pore sizes (e.g., 5-10 μm) [33]. | Label-free, antigen-agnostic approach; preserves cell viability; simple and cost-effective [33]. | Reduced purity due to retained leukocytes of similar size; may miss CTCs that are small or highly deformable [33]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Immunomagnetic Negative Enrichment of CTCs

This protocol describes a negative selection method to isolate CTCs without relying on tumor-specific surface markers, thereby capturing a more heterogeneous population, including those undergoing epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) [35].

Workflow Overview:

Materials & Reagents:

- Blood Sample: 7.5-10 mL of peripheral blood collected in EDTA or citrate tubes.

- Density Gradient Medium: Ficoll-Paque PREMIUM.

- Biotinylated Antibodies: Anti-CD45 (pan-leukocyte), anti-CD66b (granulocyte), anti-CD16 (monocyte) [35].

- Magnetic Beads: Streptavidin-coated magnetic beads.

- Enrichment Buffer: A specially formulated buffer that functions as a density gradient medium and a solvent for cell coating, enhancing the efficiency of immunomagnetic separation [35].

- Magnetic Separation Stand.

Procedure:

- PBMC Isolation:

- Layer 10 mL of blood carefully over 5 mL of density gradient medium in a 15 mL centrifuge tube.

- Centrifuge at 400 × g for 30-40 minutes at room temperature with the brake disengaged.

- Aspirate and transfer the peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) layer (a distinct buffy coat) to a new 15 mL tube.

Antibody Incubation and Magnetic Labeling:

- Wash the PBMCs twice with 10 mL of PBS containing 2% FBS.

- Resuspend the cell pellet in 1 mL of enrichment buffer.

- Add a cocktail of biotinylated antibodies (anti-CD45, anti-CD66b, anti-CD16) to the cell suspension. Incubate for 30 minutes on a rotator at 4°C.

- Wash the cells twice with 10 mL of enrichment buffer to remove unbound antibodies.

- Resuspend the cell pellet in 1 mL of enrichment buffer. Add streptavidin-coated magnetic beads and incubate for 15 minutes on a rotator at 4°C.

Magnetic Separation:

- Place the tube in a magnetic separation stand for 5-10 minutes.

- Carefully transfer the supernatant, which contains the unlabeled, enriched CTC population, to a new tube.

- Centrifuge the supernatant to collect the CTC pellet for downstream analysis.

Protocol: High-Throughput Microfluidic Enrichment via LPCTC-iChip

This advanced protocol processes large blood volumes from leukapheresis products (leukopaks) to achieve unprecedented CTC yields, enabling deep molecular profiling [34].

Workflow Overview:

Materials & Reagents:

- Leukopak: 100-150 mL diagnostic leukapheresis product.

- LPCTC-iChip System: Comprising a debulking chip and a MAGLENS (magnetic lens) chip [34].

- Biotinylated Antibodies: Anti-CD45, anti-CD66b, anti-CD16.

- Streptavidin Magnetic Beads.

- Peristaltic Pump capable of high-flow rates.

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation:

- Obtain a leukopak, which contains a mean of 5.3 ± 2.3 billion WBCs, from approximately 5.83 liters of processed patient blood [34].

- Filter the leukopak through a 42 µm filter to remove large aggregates and clots.

Antibody Incubation:

- Incubate the entire leukopak sample with a cocktail of biotinylated antibodies against CD45, CD66b, and CD16 for 30 minutes at room temperature.

Microfluidic Processing:

- Debulking Stage: Pump the sample through the inertial separation array (debulking chip) at a high flow rate (e.g., 10-20 mL/min) to remove red blood cells, platelets, and plasma.

- Magnetic Depletion Stage: Direct the nucleated cell output to the MAGLENS chip. This chip uses force-amplifying magnetic lenses to apply a strong magnetic field, deflecting and trapping antibody- and bead-labeled WBCs. The untagged CTCs flow through the device and are collected.

- The LPCTC-iChip technology can process an entire leukopak in hours, achieving a WBC depletion of >10,000-fold and yielding thousands of CTCs per patient [34].

Protocol: Size-Based Filtration Using Microsieves

This protocol offers a straightforward, label-free method for CTC enrichment based on the larger size and lower deformability of most tumor cells compared to blood cells [33].

Materials & Reagents:

- Blood Sample: 7.5-10 mL of peripheral blood.

- Microsieve Device: Silicon or polymer membrane with uniform pores (diameter 5-10 µm).

- Lysis Buffer: For optional red blood cell (RBC) lysis.

- Fixative: 4% Paraformaldehyde (PFA) for cell fixation.

- Permeabilization Buffer: 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS.

- Staining Antibodies: Anti-cytokeratin (CK), anti-CD45, and DAPI.

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation (Optional):

- Lyse red blood cells using a commercial lysis buffer to reduce sample volume and cellular debris. Alternatively, use whole blood directly.

Filtration:

- Load the prepared blood sample onto the microsieve device.

- Apply a gentle vacuum or positive pressure to drive the sample through the membrane. CTCs and large leukocytes are retained on the membrane, while smaller blood cells pass through.

- Wash the membrane with PBS to remove non-specifically bound cells.

On-Device Staining and Analysis:

- Fix the cells on the membrane with 4% PFA for 15 minutes.

- Permeabilize the cells with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 10 minutes.

- Stain with anti-CK (for epithelial CTCs), anti-CD45 (to identify contaminating leukocytes), and DAPI (to label nuclei) for 1 hour.

- Image the membrane using fluorescence microscopy. CTCs are typically identified as CK+/CD45-/DAPI+ cells.

Performance Metrics and Data Analysis

Evaluating the performance of an isolation technique is crucial. The table below defines and summarizes target values for key performance metrics.

Table 2: Key Performance Metrics for CTC Enrichment Technologies

| Performance Metric | Definition & Calculation | Reported Performance Ranges |

|---|---|---|