Molecular Techniques in Cancer Diagnostics: A Comprehensive Comparison for Precision Oncology

This article provides a systematic comparison of established and emerging molecular techniques for cancer diagnostics, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Molecular Techniques in Cancer Diagnostics: A Comprehensive Comparison for Precision Oncology

Abstract

This article provides a systematic comparison of established and emerging molecular techniques for cancer diagnostics, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of methods from PCR to Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS), details their specific applications in hereditary cancer testing, therapy selection, and minimal residual disease monitoring, and addresses key optimization challenges. A critical validation framework is presented to compare the analytical performance, clinical utility, and cost-effectiveness of these techniques, with an integrated analysis of how artificial intelligence is reshaping molecular diagnostics. The content synthesizes current evidence to guide technology selection, research direction, and clinical translation in the era of precision oncology.

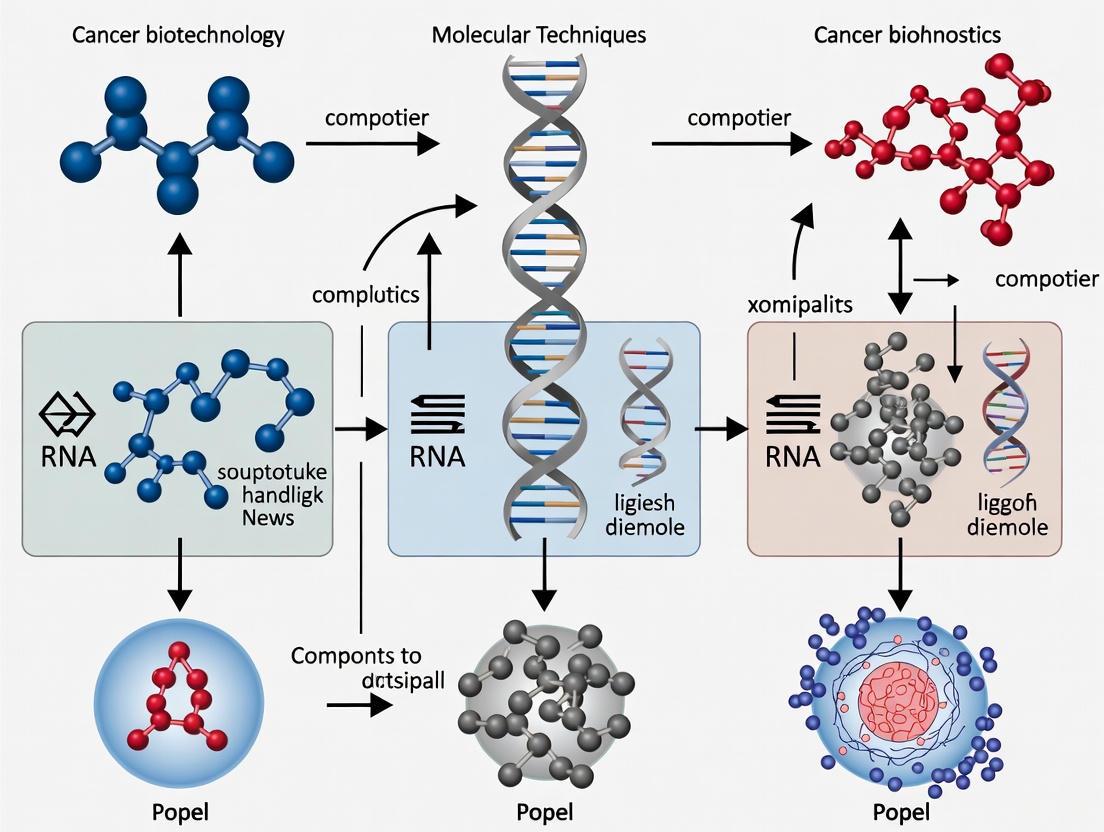

The Molecular Toolkit: Core Principles and Technological Evolution in Cancer Diagnostics

The evolution of molecular diagnostics has fundamentally transformed cancer research and clinical practice, shifting the paradigm from traditional methods to advanced techniques capable of detecting biomarkers at the single-molecule level. This comparison guide objectively evaluates the performance of DNA-based and protein-based detection technologies, providing researchers with critical insights into their applications, limitations, and complementary roles in oncology. As liquid biopsy approaches gain prominence for non-invasive cancer detection, understanding the technical capabilities of these platforms becomes essential for advancing personalized medicine and improving patient outcomes through earlier detection and monitoring.

Performance Comparison of Molecular Detection Techniques

The table below summarizes the key performance characteristics of major molecular diagnostic techniques used in cancer research, highlighting their respective strengths and limitations.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Cancer Diagnostic Techniques

| Technique | Biomarker Type | Sensitivity | Specificity | Variant Detection Limit | Key Applications | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein-based MCED [1] | Proteins/Antibodies | 100% (Overall); 100% (Stage I) | 97% (Overall) | N/A | Multi-cancer early detection, Tissue-of-origin identification | Limited to predefined protein panel; early validation stage |

| Digital PCR [2] | Nucleic Acids (DNA/RNA) | High for abundant mutations | High | 0.1% VAF | Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) detection, rare mutation identification | Limited multiplexing capability; sensitive to inhibitors |

| BEAMing [2] | Nucleic Acids (DNA) | Very High | Very High | 0.01% VAF | Ultra-sensitive ctDNA detection, rare variant quantification | Technically complex; labor-intensive; costly |

| qPCR [3] | Nucleic Acids (DNA/RNA) | Moderate | Moderate | 1-10% VAF | Gene expression analysis, mutation screening | Limited sensitivity for rare variants; requires calibration curves |

| Next-Generation Sequencing [3] | Nucleic Acids (DNA/RNA) | Variable (panel-dependent) | High | 1-5% VAF (standard); lower with deep sequencing | Comprehensive mutation profiling, biomarker discovery | Higher cost; complex data analysis; longer turnaround time |

Table 2: Tissue-of-Origin Accuracy of Protein-Based MCED Test [1]

| Cancer Type | Sample Size | Sensitivity | Specificity | TOO Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast | 61 | 100% | 96.6% | 98% |

| Lung | 43 | 100% | 97% | 98% |

| Colorectal | 13 | 100% | 100% | 98% |

| Ovarian | 13 | 100% | 100% | 98% |

| Pancreatic | 11 | 100% | 100% | 98% |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protein-Based Multi-Cancer Early Detection (MCED) Testing

Sample Preparation and Biomarker Panel [1]

- Sample Collection: Serum samples are procured from established biorepositories with documented informed consent and IRB approval. Samples from cancer patients with confirmed histological diagnosis prior to treatment and healthy controls are selected.

- Biomarker Analysis: A 16-parameter protein biomarker panel is analyzed, including:

- Extracellular Protein Kinase A (xPKA) activity quantified using MESACUP Protein Kinase Assay Kit

- Additional kinase activities measured with analogous assays

- Cancer-associated antibodies (IgG, IgM) quantified using standard ELISA protocols

- xPKA Activity Measurement: 108 μL serum samples are mixed with 12 μL activating buffer and incubated at room temperature for 30 minutes. Activated samples are combined with reaction buffer with/without protein kinase A inhibitor PKI. The mixture is incubated with immobilized peptide substrate for 30 minutes at 25°C with agitation. Peptide phosphorylation is detected using biotinylated phosphoserine antibodies followed by peroxidase-conjugated streptavidin with colorimetric TMB substrate detection.

Data Analysis and Classification [1]

- A supervised, rule-based classification framework is developed for cancer detection and tissue-of-origin assignment

- Initial pattern discovery utilizes quantitative biomarker distribution analysis through box plots and summary statistics

- Optimal threshold values for each biomarker are established where separation between groups is maximized

- Cancer-type-specific conditional rules are developed using if-then logic structures

- Cross-reactivity between cancer types is resolved through incorporation of additional biomarkers or fine-tuning threshold values

- Statistical analysis is performed using SAS Version 9.4 with cross-validation using 80-20 data splitting

Sample Partitioning

- The reaction mixture containing target nucleic acid, primers, and probes is segmented into numerous equally sized partitions

- Two primary methods are employed:

- Droplet Digital PCR: Reaction mixture is emulsified into thousands of water-in-oil droplets

- Microwell Arrays: Reaction mixture is distributed into plates containing tens of thousands of small wells

Amplification and Detection

- PCR amplification is performed within each partition

- Partitions with target DNA are differentiated from those without target based on fluorescence signal

- Target nucleic acid copy number per partition is determined using a Poisson model based on positive partitions and total partition count

- This binary approach (on/off) makes digital PCR more immune to factors affecting amplification efficiency compared to qPCR

Bead-Based Amplification

- Hundreds of millions of water-in-oil droplets are generated, each potentially containing a single target DNA molecule and a single magnetic bead

- Within each droplet, target DNA is amplified using PCR, resulting in thousands of copies attached to each bead

- Beads covered in amplified DNA are extracted from emulsion using magnetic separation techniques

Mutation Detection

- Beads are differentially stained with distinct fluorophores to identify mutant and wild-type DNA molecules

- Beads are counted using flow cytometry

- This approach achieves a limit of detection of 0.01%, an order of magnitude improvement over conventional digital PCR

Visualization of Molecular Detection Workflows

Protein-Based MCED Test Workflow

Nucleic Acid Detection Techniques Comparison

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Molecular Cancer Diagnostics

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Detection Reagents | MESACUP Protein Kinase Assay Kit [1] | Quantifies extracellular PKA activity in serum samples | Measures net xPKA activity with high reproducibility (3.7% CV) |

| Phosphoserine antibodies [1] | Detection of phosphorylated peptides in kinase assays | Used with peroxidase-conjugated streptavidin for colorimetric detection | |

| TMB substrate [1] | Colorimetric detection in ELISA-based protein assays | 60-minute incubation with acid stop solution; read at 450nm | |

| Nucleic Acid Amplification | PCR primers & probes [3] | Target-specific amplification in qPCR/digital PCR | Design critical for specificity; modified for real-time detection |

| Reverse transcriptase [3] | cDNA synthesis for RNA analysis in RT-PCR | Essential for analyzing gene expression biomarkers | |

| Sample Processing | Protein kinase inhibitors [1] | Specific inhibition in kinase activity assays | PKI inhibitor used at 0.5μM concentration for net activity calculation |

| Magnetic beads [2] | Nucleic acid capture in BEAMing technology | Enable single molecule to single bead conversion for ultra-sensitive detection | |

| Specialized Tools | SCOPE tool [4] | Targeted capture of DNA-binding proteins | Uses guide RNA and special amino acid (AbK) for UV-crosslinking |

| Mass spectrometry reagents [2] | Protein identification in novel tools | Used with SCOPE for identifying captured DNA-binding proteins |

Discussion and Future Perspectives

The comparison of molecular techniques reveals a complementary relationship between nucleic acid and protein-based approaches in cancer diagnostics. While DNA-based methods like digital PCR and BEAMing provide exceptional sensitivity for detecting rare mutations, protein-based MCED tests offer the advantage of direct functional relevance to cancer biology and robust early-stage detection [1] [2].

The emerging trend toward single-molecule detection sensitivity represents a significant advancement in molecular diagnostics [2]. These approaches overcome limitations of conventional techniques by detecting rare biomarkers that might be overlooked by ensemble averaging methods. The development of novel tools like SCOPE, which enables precise identification of DNA-binding proteins at specific genomic locations, further expands the toolkit available for cancer research [4].

For researchers and drug development professionals, the selection of appropriate diagnostic platforms should consider the specific application context. Nucleic acid techniques excel in tracking known mutations and monitoring treatment response, while protein-based approaches show promise in early detection across multiple cancer types where mutation profiles may not be predetermined. The integration of both approaches in complementary diagnostic strategies likely represents the future of comprehensive cancer detection and monitoring.

The invention of the Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) in 1986 revolutionized molecular biology by providing a means to exponentially amplify specific DNA sequences. [5] This foundational technique has since evolved through several generations, each enhancing quantitative capabilities and application scope. Second-generation quantitative PCR (qPCR), also known as real-time PCR, introduced fluorescence monitoring to enable nucleic acid quantification during amplification. [6] [5] Reverse Transcription PCR (RT-PCR) combines reverse transcription of RNA into complementary DNA (cDNA) with amplification, making it crucial for gene expression analysis and RNA virus detection. [6] The third generation, digital PCR (dPCR), provides absolute quantification by partitioning samples into thousands of individual reactions, representing the most significant recent advancement in PCR technology. [5] [7] Within cancer diagnostics, these techniques enable detection of genetic mutations, expression profiling, and monitoring of minimal residual disease through highly sensitive and specific molecular analysis.

Technology Comparison: Principles, Strengths, and Limitations

Core Principles and Workflows

Quantitative PCR (qPCR) monitors DNA amplification in real-time using fluorescent dyes or probes. The cycle at which fluorescence crosses a threshold (Cq or Ct value) is proportional to the initial target amount, quantified against a standard curve. [6] [8] RT-PCR begins with reverse transcription of RNA to cDNA followed by standard qPCR amplification, allowing quantification of RNA transcripts. [6] Digital PCR (dPCR) partitions a PCR reaction into thousands of nanoreactions, performs endpoint amplification, and applies Poisson statistics to the ratio of positive to negative partitions for absolute quantification without standard curves. [6] [5]

Comparative Performance Characteristics

Table 1: Technical comparison of PCR technologies for cancer research applications

| Parameter | qPCR | RT-PCR | dPCR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantification Method | Relative (requires standard curve) | Relative (requires standard curve) | Absolute (Poisson statistics) |

| Precision | ++ | ++ | +++ |

| Sensitivity | Detects down to <0.1% VAF [9] | Similar to qPCR | Superior for rare targets (<0.1%) [6] [8] |

| Dynamic Range | Large (up to 7-8 logs) [6] | Large | Limited by partition count [6] |

| Throughput | High (384-well format) [8] | High | Medium (up to 96 samples) [8] |

| Tolerance to Inhibitors | Moderate | Moderate | High [6] [8] |

| Multiplexing Capability | + | + | +++ [6] |

| Cost Considerations | Lower instrument and per-sample cost [8] | Similar to qPCR | Higher instrument cost, no standard curve needed [6] |

Table 2: Application suitability in cancer diagnostics research

| Application | Recommended Technology | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Gene Expression Profiling | qPCR/RT-PCR | High throughput, well-established protocols [9] |

| Rare Mutation Detection | dPCR | Superior sensitivity for variants <1% [6] [5] |

| Liquid Biopsy Analysis | dPCR | Excellent for low-abundance ctDNA [8] [10] |

| Copy Number Variation | qPCR/dPCR | dPCR offers absolute quantification [6] |

| Treatment Response Monitoring | qPCR/RT-PCR/dPCR | Choice depends on required sensitivity [11] |

| High-Throughput Screening | qPCR/RT-PCR | 384-well format, automation friendly [8] [9] |

Key Advantages and Limitations

qPCR/RT-PCR Advantages: Established gold standard with extensive validated protocols; superior throughput with 384-well formats; lower initial investment and operational costs; broad dynamic range suitable for most applications; capable of detecting fold changes greater than 2-fold. [6] [8] [9]

qPCR/RT-PCR Limitations: Requires standard curves for quantification; relatively lower precision for small fold differences (<2-fold); more susceptible to PCR inhibitors; limited sensitivity for very rare targets (<0.1%). [6] [12]

dPCR Advantages: Absolute quantification without standard curves; higher precision and reproducibility; superior sensitivity for rare targets; enhanced tolerance to inhibitors; better performance for complex samples. [6] [8] [5]

dPCR Limitations: Lower throughput; higher instrument costs; limited dynamic range requiring sample dilution for high concentrations; more expensive consumables. [6] [8] [12]

Experimental Data and Performance Benchmarks in Cancer Research

Sensitivity and Detection Limits

dPCR demonstrates superior sensitivity for low-abundance targets critical in cancer diagnostics. In studies comparing BCR-ABL1 monitoring for chronic myeloid leukemia, dPCR reliably quantified low-level transcript copies but required protocol adaptations to surpass qPCR sensitivity at very low levels (<0.1% BCR-ABL1IS). [11] For liquid biopsy applications, dPCR can detect mutant alleles in circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) at frequencies as low as 0.001%, significantly below qPCR capabilities. [6] [5] This exceptional sensitivity enables earlier detection of residual disease and emerging treatment resistance.

Precision and Reproducibility

dPCR provides significantly improved precision, with much lower coefficients of variation compared to qPCR. [6] This enhanced reproducibility stems from dPCR's binary detection system and resistance to amplification efficiency variations. In copy number variation studies, dPCR can resolve differences below the twofold limit of qPCR, providing tighter confidence intervals with fewer replicates. [6] This precision is particularly valuable for longitudinal monitoring of cancer patients where small changes in biomarker levels have clinical significance.

Tolerance to Complex Samples

dPCR demonstrates superior performance with challenging sample types common in cancer research. Partitioning the reaction mixture dilutes inhibitors present in clinical samples like plasma, FFPE tissues, and liquid biopsies, maintaining amplification efficiency where qPCR would be compromised. [6] [8] This robustness makes dPCR particularly valuable for analyzing samples with high background DNA, such as detecting rare mutations in liquid biopsies where wild-type sequences vastly outnumber mutant alleles. [6]

Experimental Protocols for Cancer Research Applications

qPCR Protocol for Gene Expression Analysis in Tumor Tissues

Sample Preparation: Extract total RNA from fresh-frozen or FFPE tumor tissues using silica-membrane columns with DNase treatment. Assess RNA quality and concentration spectrophotometrically. [9]

Reverse Transcription: Convert 500ng-1μg total RNA to cDNA using reverse transcriptase with oligo(dT) and/or random hexamer primers in 20μL reaction volume. [6]

qPCR Setup: Prepare reactions with cDNA template, target-specific primers/probes, and qPCR master mix. Run samples in triplicate alongside standard curves and no-template controls. [6] [9]

Thermal Cycling: Initial denaturation at 95°C for 2 minutes, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 seconds and 60°C for 1 minute on a real-time PCR instrument. [9]

Data Analysis: Calculate relative gene expression using the 2^(-ΔΔCt) method with normalization to reference genes. [6]

dPCR Protocol for Rare Mutation Detection in Liquid Biopsies

Cell-Free DNA Extraction: Isolate ctDNA from plasma using specialized circulating nucleic acid kits. Quantify using fluorometry. [5]

Assay Design: Design primer-probe sets to specifically detect mutant alleles while minimizing wild-type amplification. Include appropriate controls. [6]

Partitioning: Mix dPCR supermix, template DNA, and assays. Load onto dPCR plates for automated partitioning into nanoscale reactions. [8] [5]

Amplification: Perform endpoint PCR amplification with optimized cycling conditions for the partition system. [5]

Reading and Analysis: Count positive and negative partitions using fluorescence detection. Apply Poisson correction for absolute quantification of mutant alleles. [6] [5]

Technology Selection Guide for Cancer Research Applications

Decision Factors for Technology Selection

Choose qPCR/RT-PCR when: Processing large sample numbers requiring high throughput; conducting relative quantification with available standards; working with moderate to high abundance targets; operating with budget constraints; requiring established, validated protocols for regulated environments. [8] [9]

Choose dPCR when: Absolute quantification without standards is essential; detecting rare mutations or low-abundance targets (<1%); working with inhibitor-containing samples; requiring maximum precision and reproducibility; analyzing copy number variations with high precision. [6] [8] [10]

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential research reagents for PCR-based cancer diagnostics

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction | Circulating nucleic acid kits, FFPE RNA/DNA kits, magnetic bead-based systems | Isolation of high-quality nucleic acids from clinical specimens [13] [9] |

| Reverse Transcriptase | Moloney murine leukemia virus (M-MLV), avian myeloblastosis virus (AMV) | cDNA synthesis from RNA templates for RT-PCR [6] |

| PCR Master Mixes | Hot-start polymerases, inhibitor-resistant enzymes, probe-based mixes | Provides core components for amplification with enhanced specificity [9] |

| Fluorescent Probes/Dyes | Hydrolysis probes (TaqMan), molecular beacons, intercalating dyes (SYBR Green) | Detection and quantification of amplified products [6] [5] |

| Reference Standards | Synthetic oligonucleotides, gBlocks, reference genes (GAPDH, ACTB) | Standard curves for qPCR, quality control, normalization [6] |

| Partitioning Reagents | Droplet generation oil, surfactants, nanowell chips | Creation of individual reaction chambers for dPCR [5] |

Future Perspectives and Emerging Trends

PCR technologies continue evolving to address emerging needs in cancer diagnostics. Microfluidic integration is enabling miniaturized dPCR systems with higher partition densities and reduced costs. [5] [7] Multiplexing capabilities are expanding with advanced probe chemistries allowing simultaneous quantification of multiple targets from limited samples. [6] [9] Artificial intelligence and machine vision applications are enhancing data analysis accuracy, particularly for dPCR partition classification. [7] The convergence of PCR with point-of-care testing through isothermal methods and portable systems promises to decentralize cancer molecular diagnostics. [12] [7] As cancer diagnostics increasingly relies on liquid biopsies and minimal residual disease monitoring, dPCR's exceptional sensitivity positions it as a cornerstone technology, while qPCR remains the workhorse for high-throughput applications requiring robust, cost-effective solutions. [6] [5] [9]

Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) represents a paradigm shift in molecular analysis, enabling the simultaneous sequencing of millions to billions of DNA fragments in a single run [14] [15]. This massive parallelism, the core principle of NGS technology, has fundamentally transformed biomedical research and clinical diagnostics by providing unprecedented throughput, speed, and cost-efficiency compared to traditional Sanger sequencing [14] [16]. Often termed massively parallel sequencing, NGS has reduced the cost of genome sequencing by over 96%, making large-scale genomic studies and routine clinical application a practical reality [14]. The technology's versatility allows for comprehensive profiling across multiple molecular layers—including the genome, transcriptome, and epigenome—making it an indispensable tool in the era of precision medicine, particularly in oncology [17] [15].

The following diagram illustrates the core NGS workflow, from sample preparation to data analysis, highlighting the parallel processing of millions of DNA fragments.

Figure 1: The Core NGS Workflow. This process demonstrates the transformation of a biological sample into actionable genetic data through massive parallel sequencing.

NGS Versus Traditional Sequencing Methods

The transition from Sanger sequencing to NGS represents one of the most significant technological advancements in modern biology. While Sanger sequencing, developed in the 1970s, provides high accuracy for reading single DNA fragments, its low throughput makes large-scale projects like whole-genome sequencing prohibitively time-consuming and expensive [14] [16]. The Human Genome Project, which relied on Sanger sequencing, took over a decade and cost nearly $3 billion to complete [14]. In contrast, NGS can sequence an entire genome in days for under $1,000, demonstrating a dramatic improvement in efficiency and accessibility [14].

The table below provides a detailed comparison of these sequencing technologies across critical performance parameters.

Table 1: Performance Comparison: Sanger Sequencing vs. Next-Generation Sequencing

| Feature | Sanger Sequencing | Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) |

|---|---|---|

| Throughput | Low (single fragment per reaction) | Ultra-high (millions to billions of fragments per run) [14] |

| Cost per Genome | High (billions for Human Genome Project) | Significantly lower (96% decrease, under $1,000) [14] |

| Speed | Slow (days for individual genes) | Rapid (whole genomes in days, targeted panels in hours) [14] |

| Accuracy | Very high (gold standard for validation) | High, with deep coverage providing robust variant detection [14] |

| Scalability | Limited to small regions or single genes | Highly scalable, from targeted panels to whole genomes [14] |

| Primary Clinical Utility | Ideal for sequencing single genes or validating specific mutations [16] | Detects a broad spectrum of mutations and structural variants; essential for comprehensive genomic profiling [16] [17] |

This comparative advantage makes NGS uniquely suited for comprehensive genomic profiling (CGP) in oncology, where it can simultaneously analyze hundreds of cancer-related genes to identify targetable mutations, resistance mechanisms, and biomarkers like tumor mutational burden (TMB) from a single, often limited, tissue sample [17] [18].

Experimental Protocols for NGS in Cancer Research

Implementing NGS in a research or diagnostic setting requires a rigorous, multi-stage process to ensure the generation of high-quality, reliable data. The following section details the standard protocols for key NGS applications in cancer genomics.

Protocol for Targeted Gene Panel Sequencing (e.g., for Solid Tumors)

Objective: To identify somatic mutations, copy number variations (CNVs), and gene fusions in a defined set of cancer-related genes from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tumor tissue or liquid biopsy samples [17].

Step-by-Step Workflow:

- Nucleic Acid Extraction: Extract and quantify high-quality DNA from the tumor sample. For FFPE tissue, assess DNA fragmentation and degradation. For liquid biopsy, isolate cell-free DNA (cfDNA) from plasma [17].

- Library Preparation:

- Fragmentation: Use enzymatic or physical methods to shear DNA into fragments of 100-800 base pairs [14].

- Adapter Ligation: Attach platform-specific adapter sequences to both ends of each fragment. These adapters contain molecular barcodes (indexes) to allow for multiplexing—pooling multiple samples in a single sequencing run [14] [16].

- Target Enrichment: Hybridize the library to biotinylated RNA or DNA probes designed to capture exons of several hundred cancer-associated genes. Wash away non-hybridized fragments and elute the enriched target DNA. This step is crucial for focusing sequencing power on relevant genomic regions [14] [17].

- PCR Amplification: Amplify the enriched library to generate enough material for sequencing [14].

- Sequencing: Load the final library onto a sequencer (e.g., Illumina, Ion Torrent). The system performs clonal amplification (e.g., via bridge amplification on a flow cell) and sequencing-by-synthesis, generating millions of short reads [14] [16] [15].

- Data Analysis:

- Primary Analysis: Base calling and quality score (e.g., Q30, indicating 99.9% accuracy) assignment [14].

- Secondary Analysis: Align reads to a reference genome (e.g., GRCh38) and perform variant calling to identify SNPs, indels, and CNVs, generating a Variant Call Format (VCF) file [14].

- Tertiary Analysis & Interpretation: Annotate variants using databases (e.g., dbSNP, ClinVar), filter results, and classify variants according to guidelines (e.g., ACMG) into categories such as Pathogenic, Benign, or Variant of Uncertain Significance (VUS) [14].

Protocol for Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS) for Epigenomics

Objective: To generate a single-base resolution map of DNA methylation (5-methylcytosine, 5mC) across the entire genome [19].

Step-by-Step Workflow:

- DNA Extraction & Quality Control: Isolate genomic DNA and ensure high molecular weight and purity.

- Library Preparation & Bisulfite Conversion:

- Fragment DNA and prepare a standard NGS library with adapters.

- Treat the library with sodium bisulfite. This chemical conversion deaminates unmethylated cytosines to uracils (which are read as thymines during sequencing), while leaving methylated cytosines unchanged [19].

- Sequencing: Perform deep whole-genome sequencing on the converted library. This requires high coverage to confidently call methylation status.

- Data Analysis:

- Map the bisulfite-converted reads to a reference genome using specialized aligners that account for C-to-T conversions.

- Calculate the methylation percentage at each cytosine position by comparing the number of reads reporting a C (methylated) versus a T (unmethylated) [19].

Key NGS Applications in Cancer Diagnostics and Research

NGS has become the cornerstone of precision oncology, enabling a multi-faceted approach to understanding and treating cancer. Its applications span from comprehensive tissue analysis to non-invasive monitoring.

Comprehensive Genomic Profiling (CGP) in Tissue

CGP utilizes NGS to detect a wide range of alterations—including point mutations, indels, CNVs, gene fusions, and microsatellite instability (MSI)—across a large panel of genes in a single assay [17]. This approach is more efficient than sequential single-gene tests, conserving precious tissue samples and accelerating diagnostic turnaround times. CGP is critical for identifying actionable mutations that can be matched with targeted therapies, such as EGFR inhibitors in lung cancer or PARP inhibitors in BRCA-mutated cancers [16] [17]. It also enables the calculation of tumor mutational burden (TMB), a biomarker for response to immunotherapy [18].

Liquid Biopsy and Circulating Tumor DNA (ctDNA) Analysis

Liquid biopsy involves the sequencing of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA)—fragmented DNA released by tumor cells into the bloodstream [17]. NGS-based liquid biopsy offers a non-invasive method for cancer detection, genotyping, and monitoring treatment response. Key applications include:

- Identifying Actionable Mutations: Detecting targetable mutations from blood, especially when tissue biopsy is unfeasible [17].

- Monitoring Treatment Response: Serial tracking of ctDNA levels and mutation profiles (e.g., variant allele frequency (VAF)) to assess therapy efficacy and detect the emergence of resistance mechanisms earlier than radiographic imaging [17].

- Minimal Residual Disease (MRD) Detection: Identifying molecular evidence of residual cancer after curative-intent treatment, predicting risk of relapse [16] [17].

The following diagram outlines the typical workflow for applying NGS in cancer research, from sample choice to clinical decision-making.

Figure 2: NGS Applications in Cancer Research and Clinical Decision-Making. This workflow shows how different sample types and NGS applications generate specific data types that inform clinical actions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Platforms

Selecting the appropriate reagents and technologies is fundamental to successful NGS experimentation. The table below catalogs key solutions and their functions for NGS-based cancer genomics studies.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for NGS-Based Cancer Genomics

| Category | Item | Function in the NGS Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Library Preparation | Fragmentation Enzymes | Shears DNA into uniformly sized fragments for optimal sequencing [14]. |

| Adapter Oligos & Ligation Kits | Attaches platform-specific sequences to DNA fragments for binding and indexing [14] [16]. | |

| Hybridization Capture Probes | Enriches for target genomic regions (e.g., cancer gene panels) from a whole-genome library [14] [17]. | |

| Methylation-Specific Kits | Contains reagents for bisulfite conversion and library preparation for epigenomic studies [19]. | |

| Sequencing Platforms | Illumina (e.g., NovaSeq) | Uses sequencing-by-synthesis with reversible dye-terminators for high-throughput, accurate short-read sequencing [20] [15]. |

| Ion Torrent (e.g., Genexus) | Employs semiconductor sequencing detecting pH change during nucleotide incorporation; known for rapid turnaround [20] [15]. | |

| PacBio (HiFi) | Provides long-read sequencing with high accuracy (>99.9%), ideal for resolving complex structural variants and phasing [20] [15]. | |

| Oxford Nanopore (e.g., MinION) | Offers real-time, long-read sequencing by measuring electrical current changes as DNA passes through a nanopore [20] [15]. | |

| Bioinformatics Tools | Alignment Software (e.g., BWA) | Maps sequence reads to a reference genome to determine their genomic origin [14]. |

| Variant Callers (e.g., GATK) | Identifies mutations (SNPs, indels) by comparing the aligned sample sequence to the reference [14]. | |

| Annotation Databases (e.g., ClinVar, COSMIC) | Provides biological and clinical context for identified variants to aid interpretation [14] [17]. |

Next-Generation Sequencing has unequivocally established itself as the technological backbone of modern genomic medicine. Its ability to provide comprehensive, high-resolution insights into the genome, transcriptome, and epigenome from minimal sample input has made it particularly transformative for cancer research and diagnostics [14] [17] [18]. By enabling Comprehensive Genomic Profiling and non-invasive liquid biopsy monitoring, NGS guides therapeutic decisions, monitors treatment efficacy, and detects resistance, thereby fulfilling the core promise of precision oncology [16] [17].

While challenges related to data interpretation, standardization, and accessibility remain, ongoing advancements in sequencing chemistry, bioinformatics, and the integration of long-read technologies continue to push the boundaries [17] [15]. The future of NGS lies in its deeper integration with other 'omics' data and its evolution into a more accessible, automated tool that can deliver actionable insights for an ever-broader population of cancer patients, ultimately improving outcomes through molecularly driven care.

The tumor immune microenvironment (TIME) is a complex ecosystem comprising cancer cells, immune cells, stromal cells, and extracellular matrix components that collectively dictate tumor progression, therapeutic response, and patient outcomes [21]. Molecular imaging has emerged as an indispensable tool for visualizing and quantifying these dynamic interactions in vivo, providing non-invasive, real-time, and longitudinal insights that are transforming cancer diagnostics and therapeutic monitoring [22] [21]. By targeting specific biological processes within the TIME, imaging probes enable researchers and clinicians to move beyond anatomical assessment to functional and molecular characterization, paving the way for personalized medicine approaches in oncology [23] [24].

This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of three cornerstone molecular imaging modalities—Positron Emission Tomography (PET), Single-Photon Emission Computed Tomography (SPECT), and Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)—for visualizing the TIME. We objectively evaluate their performance characteristics, present supporting experimental data, and detail methodologies for key applications, equipping researchers with the practical knowledge needed to select appropriate techniques for specific research questions in cancer immunology and drug development.

Comparative Analysis of Imaging Modalities

The following table summarizes the fundamental principles, strengths, and limitations of PET, SPECT, and MRI for probing the tumor immune microenvironment.

Table 1: Technical Comparison of Molecular Imaging Modalities for TIME Analysis

| Feature | PET | SPECT | MRI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Underlying Principle | Detects gamma rays from positron-emitting radiotracers [22] | Detects gamma rays from single-photon emitting radiotracers [21] | Utilizes magnetic fields and radio waves to image proton density/relaxation [22] [21] |

| Sensitivity | High (pM-nM range for tracers) [25] | Moderate (nM range) [25] | Low (μM-mM range) [21] |

| Spatial Resolution | Moderate (4–6 mm) [25] | Low (8–10 mm) [25] | High (μm-mm range) [21] |

| Tissue Penetration | Unlimited | Unlimited | Unlimited |

| Quantification Capability | Excellent (absolute quantification possible) | Good (semi-quantitative) | Variable (semi-quantitative) |

| Molecular Probe Types | Radiotracers (e.g., [¹⁸F], [¹¹C], [⁶⁸Ga]) [23] [26] | Radiotracers (e.g., [⁹⁹mTc], [¹¹¹In]) [21] | Paramagnetic/ superparamagnetic agents (e.g., Gd-, Fe-based) [24] [21] |

| Key Advantage | High sensitivity for tracking immune cell trafficking and receptor expression | Versatility for multi-probe imaging; wider tracer availability | Exceptional soft-tissue contrast and anatomical detail without ionizing radiation [21] |

| Primary Limitation | Limited anatomical context (requires CT/MRI fusion) [21] | Lower resolution and sensitivity vs. PET [21] | Low molecular sensitivity; longer acquisition times [21] |

| Representative Applications in TIME | Immunometabolism ([¹⁸F]FDG), T-cell activation ([⁸⁹Zr]CD8+ mAb) [22] | Imaging macrophage activity, vascular leakage | Visualizing immune cell infiltration via iron oxide nanoparticles [21] |

Targeted Molecular Probes and Their Applications

This section details specific molecular probes for key TIME components, comparing their performance across modalities with supporting experimental data.

Table 2: Comparison of Molecular Probes for Targeting TIME Components

| TIME Target / Process | Probe Name | Imaging Modality | Target / Mechanism | Key Experimental Findings & Performance Data |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T-cell Infiltration | [⁸⁹Zr]CD8+ mAb | PET/CT | Binds to CD8+ T-cell surface markers | Non-invasive assessment of CD8+ tumor infiltration levels in patients undergoing immunotherapy for solid tumors [22]. |

| Immunometabolism | [¹⁸F]FDG | PET/CT | Marker of glucose metabolism (glycolysis) | High prognostic value in lymphoma; used with Deauville criteria [23]. AUCs >0.85 reported for predicting response to ICIs in HCC [25]. |

| Oxidative Stress | [¹⁸F]FSPG | PET | Substrate for system xc- (cystine-glutamate antiporter) | In animal models, changes in uptake preceded glycolytic changes ([¹⁸F]FDG) and tumor volume changes on CT [23]. |

| Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts (CAFs) | [⁶⁸Ga]FAPI-46 | PET/CT | Inhibits Fibroblast Activation Protein (FAP) on CAFs | Predictor of short overall survival in solid tumours [23]. In breast cancer NAC, uptake changes after 2 cycles predicted pathological complete response [23]. |

| Receptor Tyrosine Kinases (HER2) | [⁸⁹Zr]Trastuzumab | PET/CT | Binds to HER2 receptor | In the ZEPHIR trial (HER2+ breast cancer), HER2 PET/CT combined with early [¹⁸F]FDG metabolic response predicted T-DM1 treatment success [23]. |

| Extracellular Matrix (Collagen) | [⁶⁸Ga]Ga-CBP8 | PET/MRI | Binds to collagen deposits | Strong correlation between tumour collagen deposition and probe uptake in PDAC mice and patients, showing potential for monitoring chemotherapy response [21]. |

| Extracellular Matrix (Collagen) | EP-3533 | MRI | Gadolinium-based collagen-binding probe | Enhanced MRI signals indicating collagen deposition in LNCaP prostate tumors, validated histologically [21]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Applications

Protocol 1: Assessing Treatment Response with [⁶⁸Ga]FAPI PET/CT in Breast Cancer

- Tracer: [⁶⁸Ga]FAPI-46 [23].

- Imaging Schedule: Baseline PET/CT scan prior to neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC), followed by a second scan after two cycles of NAC [23].

- Image Analysis: Quantify tracer uptake in tumors using standardized uptake values (SUVmax or SUVmean). Calculate the percentage change in SUV between baseline and follow-up scans.

- Outcome Correlation: A significant decrease in [⁶⁸Ga]FAPI uptake after two cycles was found to be predictive of achieving a pathological complete response (pCR) at surgery, allowing for early identification of responders [23].

Protocol 2: Visualizing Collagen Remodeling in the TME with [⁶⁸Ga]Ga-CBP8 PET/MRI

- Tracer: [⁶⁸Ga]Ga-CBP8, a collagen-binding peptide [21].

- Imaging Procedure: Perform simultaneous PET/MRI imaging. The MRI component provides high-resolution anatomical localization of the pancreas/tumor.

- Quantification: Draw volumes of interest (VOIs) around the tumor on fused PET/MRI images. Measure mean standardized uptake values (SUVmean) within the VOI.

- Validation: In murine models of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), a strong positive correlation was observed between PET signal and ex vivo histological quantification of collagen deposition (e.g., via Picrosirius Red staining). This protocol successfully detected FOLFIRINOX chemotherapy-induced collagen accumulation in a PDAC patient [21].

Protocol 3: Imaging CD8+ T-cell Infiltration with [⁸⁹Zr]CD8+ mAb PET/CT

- Tracer: [⁸⁹Zr]-labeled anti-CD8+ monoclonal antibody [22].

- Subject Preparation: Patients undergoing immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy for solid tumors.

- Image Acquisition: Whole-body PET/CT scans are acquired at a predetermined time point (e.g., 24-48 hours) post-injection to allow for tracer biodistribution and target binding.

- Data Analysis: The level of CD8+ T-cell infiltration is assessed non-invasively by quantifying tracer uptake in tumors and, potentially, in lymphoid organs. This data provides crucial insights for predicting and monitoring immunotherapy response [22].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for TIME Molecular Imaging

| Item / Reagent | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Radiolabeled Precursors | Foundation for synthesizing PET and SPECT tracers (e.g., [¹⁸F]fluoride, [⁶⁸Ga]GaCl₃) [24]. |

| Chelators | Chemically link radioactive metals to targeting biomolecules (e.g., DOTA, NOTA for [⁶⁸Ga]) [24]. |

| Targeting Ligands | Provide specificity to molecular probes. Includes antibodies, peptides, aptamers, and small molecules [24]. |

| Contrast Agents | Enhance signal for MRI (e.g., Gadolinium-based) [24]. |

| Cell Tracking Agents | Label immune cells ex vivo for subsequent in vivo tracking (e.g., [⁸⁹Zr]Oxine, FeO nanoparticles) [21]. |

| Ex Vivo Validation Kits | Confirm imaging findings via IHC/IF staining for CD8, CD4, FoxP3, FAP, PD-L1, and collagen. |

Visualizing Experimental Workflows and Biological Pathways

The following diagrams illustrate a generalized workflow for probe development and a key immunometabolic pathway, respectively.

Diagram 1: Probe Development Workflow

Diagram 2: Key Immunometabolic Imaging Targets

Liquid biopsy represents a transformative approach in oncology, enabling the minimally invasive detection and monitoring of cancer through the analysis of tumor-derived components in bodily fluids [27]. Unlike traditional tissue biopsies, which can be invasive, difficult to repeat, and fail to capture tumor heterogeneity, liquid biopsies offer a dynamic snapshot of the tumor's genetic landscape through a simple blood draw [27] [28]. The concept centers on analyzing circulating biomarkers, with circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) emerging as the most promising analyte due to technological advances in DNA analysis [28].

ctDNA consists of short DNA fragments shed into the bloodstream by tumor cells through apoptosis or necrosis [29]. It circulates as part of cell-free DNA (cfDNA) but constitutes only a small fraction (approximately 0.1% to 1.0%) of the total cfDNA in cancer patients, presenting significant detection challenges [27] [30]. The half-life of ctDNA is relatively short (approximately 1-2.5 hours), making it a dynamic biomarker capable of providing real-time information on tumor burden and treatment response [27]. The detection of tumor-specific alterations in ctDNA—including somatic mutations, copy number variations, epigenetic changes, and fragmentation patterns—enables cancer detection, molecular profiling, and monitoring [28] [29].

Molecular Techniques for ctDNA Analysis

Comparison of Detection Platforms

The analysis of ctDNA requires highly sensitive methods due to its low concentration in blood. Currently, two main technological approaches dominate the field: PCR-based methods and next-generation sequencing (NGS). Each offers distinct advantages and limitations for different clinical and research applications [28].

Table 1: Comparison of Major ctDNA Detection Platforms

| Technology | Key Variants | Sensitivity | Multiplexing Capacity | Primary Applications | Cost & Turnaround Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCR-Based | ddPCR, BEAMing | VAF 0.01%-0.1% | Low (1-few mutations) | Treatment monitoring, MRD detection | Lower cost, Rapid (hours-days) |

| NGS | Targeted Panels, WGS, WES | VAF 0.1%-1% (varies) | High (dozens-hundreds of genes) | Comprehensive profiling, biomarker discovery | Higher cost, Longer (days-weeks) |

| Emerging Methods | Methylation Analysis, Fragmentomics | Varies | Moderate to High | Early detection, cancer origin determination | Research phase, costs varying |

PCR-based platforms, particularly droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) and BEAMing (beads, emulsion, amplification, magnetics), provide exceptional sensitivity for detecting low-frequency mutations (as low as 0.01% variant allele frequency, VAF) [28]. These methods are ideal for tracking known mutations during treatment or monitoring for minimal residual disease (MRD) [30]. However, their utility is limited to assessing a small number of predefined mutations, restricting comprehensive genomic profiling [28].

NGS-based approaches enable broad genomic profiling through targeted panels, whole-exome sequencing (WES), or whole-genome sequencing (WGS) [28]. These methods can simultaneously assess hundreds of cancer-associated genes, capturing single nucleotide variants (SNVs), insertions/deletions (Indels), copy number variations (CNVs), and structural variants (SVs) [29]. While traditional NGS struggles with very low VAFs (<0.1%), advanced error-suppression techniques and unique molecular identifiers have significantly improved sensitivity [29].

Recent technological innovations include methylation analysis, which examines DNA methylation patterns to distinguish cancer-derived DNA, and fragmentomics, which leverages the observation that ctDNA fragments exhibit different size distributions and end motifs compared to non-cancer cfDNA [28]. Machine learning approaches integrating multiple analytical methods (genomic, epigenomic, fragmentomic) have demonstrated enhanced sensitivity for early cancer detection [28].

Workflow Diagrams for ctDNA Analysis

Figure 1: Overall Workflow for ctDNA Analysis

Figure 2: ddPCR Workflow for Targeted Mutation Detection

Figure 3: NGS Workflow for Comprehensive Genomic Profiling

Performance Comparison: Experimental Data and Protocols

Analytical Sensitivity Across Platforms

Recent comparative studies have systematically evaluated the performance of different ctDNA detection platforms. A 2024 comprehensive evaluation of nine ctDNA assays revealed significant variations in sensitivity, specificity, and reproducibility, particularly at lower DNA inputs and variant allele frequencies [29].

Table 2: Performance Metrics of ctDNA Detection Platforms Across Studies

| Study & Context | Technology | Sensitivity | Specificity | Key Findings | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rectal Cancer (2025) [30] | ddPCR | 58.5% (pre-therapy) | High (not specified) | Higher detection in advanced stages; superior to NGS for localized cancer | Postoperative detection failed before most recurrences |

| NGS | 36.6% (pre-therapy) | High (not specified) | Lower detection rate vs. ddPCR (p=0.00075) | Less sensitive for MRD detection | |

| Melanoma Meta-analysis (2022) [31] | Various ctDNA assays | Pooled: 73% | Pooled: 94% | AUC 0.93 (92.87% accuracy vs. gold standard) | Sensitivity varied by country, sample source, method |

| 9-Assay Evaluation (2024) [29] | Multiple NGS assays | VAF 0.5%: ~95% (most assays) | Generally high (assay-dependent) | Sensitivity dropped substantially at VAF 0.1%; input amount critical | Inter-assay variability, especially at low VAF |

| Lung Adenocarcinoma (2021) [32] | Tissue NGS (benchmark) | 94.8% | Not specified | Detected significantly more clinically relevant alterations | Invasive procedure required |

| Plasma NGS | 52.6% (p<0.001) | Not specified | Useful when tissue unavailable | Low sensitivity limits standalone use |

A direct comparison between ddPCR and NGS in localized rectal cancer demonstrated that ddPCR detected ctDNA in 58.5% of pre-therapy plasma samples compared to 36.6% with NGS (p = 0.00075) [30]. This performance advantage was particularly evident in patients with higher clinical tumor stage and lymph node positivity [30]. The study employed a tumor-informed approach where mutations identified in tumor tissue NGS were subsequently tracked in plasma using custom ddPCR assays [30].

The 2024 multi-assay evaluation highlighted that most ctDNA assays achieved approximately 95% sensitivity for SNV detection at VAF ≥0.5% with adequate DNA input (>20ng) [29]. However, sensitivity substantially decreased at VAF 0.1%, with significant variability between platforms [29]. Assays with larger panel sizes (>1Mb) generally demonstrated lower sensitivity for low-frequency variants but provided more comprehensive genomic information [29].

Methodological Protocols

Sample Collection and Processing

Proper sample collection and processing are critical for reliable ctDNA analysis. The following protocols are adapted from recent studies [30] [29]:

- Blood Collection: 3 × 9 mL of blood collected into Streck Cell-Free DNA BCT or similar cfDNA preservation tubes [30]

- Processing: Plasma separation within 2-6 hours of collection by double centrifugation (e.g., 800 × g for 10 minutes, then 14,000 × g for 10 minutes) [29]

- Storage: Plasma stored at -80°C until cfDNA extraction [30]

- cfDNA Extraction: Automated extraction systems (e.g., QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid Kit, MagMax Cell-Free DNA Isolation Kit) following manufacturer protocols [29]

- Quality Control: cfDNA quantified using fluorometric methods (e.g., Qubit dsDNA HS Assay); fragment size distribution assessed (e.g., Bioanalyzer, TapeStation) [29]

- Input: 2-9 μL extracted cfDNA (approximately 10-50 ng total)

- Partitioning: Generation of approximately 20,000 droplets using droplet generator

- PCR Amplification: Endpoint PCR with mutation-specific probes (FAM-labeled) and reference probes (HEX/VIC-labeled)

- Thermal Cycling: 95°C for 10 minutes; 40 cycles of 94°C for 30 seconds and 55-60°C (assay-specific) for 60 seconds; 98°C for 10 minutes

- Detection: Droplet reading using droplet flow cytometer

- Analysis: Quantification of positive and negative droplets using vendor software; calculation of mutant copies/mL and variant allele frequency

- Input: 10-50 ng cfDNA (minimum recommended >20 ng)

- Library Preparation: End-repair, A-tailing, adapter ligation using commercial kits (e.g., Ion AmpliSeq Library Kit)

- Target Enrichment: Hybridization capture or amplicon-based (e.g., Ion AmpliSeq Cancer Hotspot Panel v2)

- Sequencing: NGS platform-specific (e.g., Illumina, Ion Torrent) to achieve minimum 5,000× deduplicated mean depth

- Variant Calling: Bioinformatic pipeline with unique molecular identifiers for error suppression; variant calling threshold typically 0.1-0.5% VAF

- Quality Metrics: On-target rate >50%, uniformity >80%, minimum coverage requirements met

Clinical Applications and Regulatory Status

Current Clinical Implementation

Liquid biopsy and ctDNA analysis have gained regulatory approval for specific clinical applications, particularly in therapy selection for advanced cancers. The FoundationOne Liquid CDx test received FDA approval as a companion diagnostic for multiple biomarkers, including:

- BRCA1/BRCA2 mutations in ovarian cancer for rucaparib treatment [33]

- ALK rearrangements in NSCLC for alectinib treatment [33]

- PIK3CA mutations in breast cancer for alpelisib treatment [33]

- BRCA1/BRCA2/ATM mutations in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer for olaparib treatment [33]

The FDA specifies that if these alterations are not detected in blood, tumor tissue testing should be performed to confirm negative results [33]. This reflects the recognized lower sensitivity of plasma-based testing compared to tissue analysis [32].

Beyond therapy selection, ctDNA analysis shows significant promise in multiple clinical domains:

- Minimal Residual Disease (MRD) Detection: Post-treatment ctDNA presence strongly predicts recurrence risk in colorectal cancer (up to 80-100% recurrence risk if ctDNA-positive) [30] [28]

- Treatment Response Monitoring: Dynamic changes in ctDNA levels often precede radiographic evidence of response or progression [27] [28]

- Early Cancer Detection: Multi-cancer early detection tests utilizing fragmentomics and methylation patterns are under investigation [28] [34]

Performance Across Cancer Types

The clinical utility of ctDNA analysis varies significantly by cancer type and stage. A meta-analysis of melanoma demonstrated 73% pooled sensitivity and 94% pooled specificity for ctDNA detection of BRAF mutations compared to tissue testing [31]. The area under the SROC curve was 0.93, indicating high diagnostic accuracy [31].

In lung adenocarcinoma, tissue-based NGS detected significantly more clinically relevant mutations (94.8% sensitivity) compared to plasma-based NGS (52.6% sensitivity, p<0.001) [32]. This performance gap was consistent across newly diagnosed and previously treated patients, suggesting tissue remains the preferred specimen when available [32].

Challenges and Research Gaps

Despite rapid advancement, ctDNA analysis faces several significant challenges that limit its widespread clinical implementation:

- Sensitivity Limitations: Current technologies struggle to detect very low VAFs (<0.1%), particularly in early-stage disease or low-shedding tumors [29]

- Preanalytical Variability: Differences in sample collection, processing, and storage significantly impact results [29]

- Inter-assay Discordance: Substantial variability exists between different ctDNA assays, especially for low-frequency variants [29] [32]

- Clonal Hematopoiesis: Age-related mutations in blood cells can confound ctDNA interpretation [29]

- Standardization Gaps: Lack of uniform protocols for sample processing, analysis, and interpretation [28] [29]

- Cost and Accessibility: NGS-based approaches remain expensive and technically demanding, limiting availability in resource-limited settings [28]

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for ctDNA Analysis

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blood Collection Tubes | Streck Cell-Free DNA BCT, CellSave Preservative Tubes | Preserves cfDNA integrity during transport/storage | Critical for preventing leukocyte lysis and background DNA release |

| cfDNA Extraction Kits | QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid Kit, MagMax Cell-Free DNA Isolation Kit | Isolation of high-quality cfDNA from plasma | Automated systems preferred for reproducibility |

| DNA Quantification | Qubit dsDNA HS Assay, Bioanalyzer High Sensitivity DNA Kit | Accurate quantification and quality assessment | Fluorometric methods superior to spectrophotometry for cfDNA |

| ddPCR Reagents | Bio-Rad ddPCR Supermix, PrimePCR ddPCR Mutation Assays | Ultrasensitive detection of known mutations | Custom probes needed for rare mutations increase costs |

| NGS Library Prep | Illumina DNA Prep, Ion AmpliSeq Library Kit, KAPA HyperPrep | Preparation of sequencing libraries | Choice impacts coverage uniformity and GC bias |

| Target Enrichment | IDT xGen Pan-Cancer Panel, Thermo Fisher Oncomine Panels | Enrichment of cancer-relevant genomic regions | Hybridization capture vs. amplicon-based approaches |

| Bioinformatics Tools | GATK, MuTect2, VarScan, Conpair | Variant calling, quality control, contamination detection | Computational methods critical for low-VAF variant detection |

Liquid biopsy analysis of ctDNA represents a paradigm shift in cancer diagnostics, offering a minimally invasive approach to tumor genotyping, treatment monitoring, and recurrence detection. The comparative data clearly demonstrates a performance trade-off between PCR-based methods (higher sensitivity for known mutations) and NGS-based approaches (broader genomic coverage). As technological advancements continue to improve sensitivity and reduce costs, ctDNA analysis is poised to become increasingly integrated into routine cancer management. However, standardization of preanalytical procedures, validation of clinical utility across cancer types and stages, and resolution of bioinformatic challenges remain essential for widespread implementation. The ongoing development of multimodal approaches combining genomic, epigenomic, and fragmentomic analyses holds particular promise for enhancing the sensitivity and specificity of liquid biopsy applications in oncology.

From Bench to Bedside: Application-Driven Selection of Molecular Diagnostics in Clinical and Research Workflows

Hereditary cancer syndromes, such as those caused by pathogenic variants in the BRCA1/2 genes or the DNA mismatch repair (MMR) genes associated with Lynch syndrome (LS), account for a significant portion of cancer predisposition. Identifying these syndromes is crucial for implementing targeted cancer surveillance, risk-reducing strategies, and therapeutic interventions. Advances in molecular techniques have revolutionized diagnostic pathways, moving beyond family history-based models to incorporate tumor sequencing and multigene panels. This guide compares the current molecular techniques for diagnosing BRCA-related cancers and Lynch syndrome, focusing on their application in clinical and research settings. We provide a structured comparison of testing methodologies, their performance, and integrated clinical workflows to inform researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Molecular Basis and Clinical Significance

BRCA1 and BRCA2 Syndromes

BRCA1 (BReast CAncer gene 1) and BRCA2 (BReast CAncer gene 2) are tumor suppressor genes that produce proteins critical for repairing damaged DNA. Harmful changes in these genes—pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants (PV)—significantly increase the lifetime risk of several cancers [35]. While traditionally associated with female breast and ovarian cancers, these mutations also confer markedly increased risks for male breast cancer, prostate cancer, and pancreatic cancer in carriers [36]. Notably, males represent half of all BRCA1/2 PV carriers, yet they undergo genetic testing at one-tenth the frequency of females, highlighting a significant gap in clinical identification [36].

Lynch Syndrome (Hereditary Non-Polyposis Colorectal Cancer)

Lynch syndrome is an autosomal dominant condition and the most frequent hereditary colorectal cancer (CRC) syndrome, accounting for 1–7% of all CRC cases [37] [38]. It is caused by germline mutations in MMR genes, primarily MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2, and EPCAM deletions. These mutations lead to microsatellite instability (MSI) and defective DNA repair, resulting in increased lifetime risks for colorectal, endometrial, gastric, ovarian, and other cancers [37] [38]. Timely molecular diagnosis is crucial for guiding endoscopic surveillance and risk-reducing interventions [38].

Comparative Analysis of Molecular Testing Techniques

Molecular diagnostics for hereditary cancer rely on various technologies, each with distinct strengths, limitations, and applications in research and clinical practice. The following table summarizes the primary techniques used for BRCA and Lynch syndrome identification.

Table 1: Comparison of Molecular Techniques for Hereditary Cancer Syndrome Identification

| Technique | Primary Application | Key Metrics/Performance | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) Multigene Panels [38] | Simultaneous analysis of multiple high- and moderate-penetrance cancer genes. | High sensitivity for point/small variants; Custom panels can cover 99% of target sequences [38]. | Cost-effective for multiple genes; higher sequencing depth than WES/WGS; focused analysis reduces incidental findings. | May not detect large copy number variations (CNVs) or large EPCAM deletions without specific design [38]. |

| Sanger Sequencing | Traditional method for single-gene testing. | High accuracy for confirming specific variants. | Low cost for a single gene; considered the gold standard. | Low throughput; not practical for analyzing multiple genes or large genes. |

| Tumor Analysis: Immunohistochemistry (IHC) [39] | Detects loss of MMR protein expression (MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2) in tumor tissue. | High negative predictive value; AUC ~0.82 for identifying MMR mutation carriers [39]. | Inexpensive; readily available in most pathology labs; pinpoints affected protein. | Does not identify the specific genetic alteration; can yield ambiguous results. |

| Tumor Analysis: Microsatellite Instability (MSI) Testing [39] | Detects hypermutability in microsatellite regions due to dMMR. | AUC ~0.77 for identifying MMR mutation carriers [39]. | Functional assay for dMMR; key biomarker for immunotherapy. | Requires paired normal tissue for optimal accuracy; does not identify the mutated gene. |

| Founder Mutation Panels [40] | Targeted testing for specific high-frequency variants in defined populations. | In Ashkenazi Jewish populations, 3 founder mutations account for most BRCA1/2 PVs [35]. | Fast and cost-effective for high-risk populations. | Will miss rare or population-specific variants; not for general population screening. |

Integrated Diagnostic Pathways and Prediction Models

Combining molecular tests with clinical criteria enhances the identification of mutation carriers. For Lynch syndrome, the integration of clinical prediction models with tumor testing has been systematically evaluated.

Table 2: Performance of Lynch Syndrome Identification Strategies [39]

| Identification Strategy | Area Under the Curve (AUC) | Clinical Utility |

|---|---|---|

| PREMM~1,2,6~ Model (Clinical/Family History Only) | 0.90 | Effective for initial risk stratification based on personal/family history. |

| Microsatellite Instability (MSI) Testing Alone | 0.77 | Good for functional assessment of dMMR but less discriminative alone. |

| Immunohistochemistry (IHC) Alone | 0.82 | Pinpoints protein loss; better performance than MSI alone. |

| PREMM~1,2,6~ + IHC | 0.94 | Excellent combined performance; recommended for integrated screening. |

| PREMM~1,2,6~ + MSI | 0.93 | Very good combined performance. |

| PREMM~1,2,6~ + IHC + MSI | 0.94 | No significant improvement over PREMM~1,2,6~ + IHC. |

For BRCA, testing indications have expanded beyond strong family history to include a personal history of specific cancers, such as male breast cancer, pancreatic cancer, and high-risk prostate cancer, as well as the presence of specific somatic tumor findings [36].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

This protocol outlines the targeted sequencing of a 9-gene panel for Lynch syndrome in a Uruguayan cohort, demonstrating a scalable in-house application.

- Step 1: Patient Selection and DNA Extraction: Recruit patients meeting clinical criteria for LS (e.g., Amsterdam II/Bethesda guidelines). Collect whole blood samples and extract genomic DNA using a commercial kit (e.g., QIAamp DNA Mini Kit). Verify DNA quality via 260/280 nm ratio and quantify using a fluorometric method (e.g., Qubit dsDNA HS Assay).

- Step 2: Custom Panel Design and Library Preparation: Design a custom AmpliSeq panel (e.g., using Ion AmpliSeq Designer) covering the coding sequences, splice junctions, and UTRs of target genes (

MLH1,MSH2,MSH6,PMS2,EPCAM,APC,MUTYH). For each patient, amplify 10 ng of genomic DNA via PCR using the custom primer pools. Construct barcoded libraries using a kit (e.g., Ion AmpliSeq Library Kit 2.0). - Step 3: Templating and Sequencing: Prepare sequencing templates using an ion emulsion PCR system (e.g., Ion Chef System). Sequence the libraries on a benchtop sequencer (e.g., Ion Torrent S5 System).

- Step 4: Data Analysis and Variant Interpretation: Map sequences to the human reference genome (e.g., hg19). Call and annotate variants. Prioritize variants based on allele frequency, in silico prediction tools (e.g., SIFT, PolyPhen), and existing pathogenicity databases. Classify variants according to the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) guidelines.

This large-scale functional study used CRISPR/Cas9 to reclassify BRCA2 variants of uncertain significance (VUS), a major challenge in clinical genetics.

- Step 1: Variant Saturation: Use CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing to introduce approximately 7,000 different variants into a specific functional domain of the BRCA2 gene in a controlled cell line model.

- Step 2: Functional Selection: Subject the pools of variant-carrying cells to a growth-based assay that selects for cells with impaired BRCA2 function. Cells with pathogenic BRCA2 variants will survive this selection, while those with benign variants will not.

- Step 3: Sequencing and Enrichment Scoring: Extract genomic DNA from the selected cell populations and sequence the targeted BRCA2 region. Calculate a functional score for each variant based on its relative abundance before and after selection.

- Step 4: Variant Reclassification: Classify variants as "pathogenic/likely pathogenic" (low functional score) or "benign/likely benign" (high functional score). Submit validated data to expert panels (e.g., NIH's ClinVar) for official reclassification, impacting clinical care.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Hereditary Cancer Genomics

| Reagent/Material Solution | Function | Example Product/Catalog Number |

|---|---|---|

| High-Quality DNA Extraction Kit | To obtain pure, high-molecular-weight genomic DNA from patient samples (blood, saliva). | QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (#51304) [38] |

| Targeted NGS Library Prep Kit | To amplify target genes and attach sequencing adapters and barcodes for multiplexing. | Ion AmpliSeq Library Kit 2.0 (#4475345) [38] |

| Ion Xpress Barcode Adapters | To individually index (barcode) each sample library for pooled sequencing. | Ion Xpress Barcode Adapters (#4474517) [38] |

| NGS Quantification Assay | To accurately quantify library concentration before sequencing. | Qubit 1X dsDNA HS Assay Kit (#Q33230) [38] |

| CRISPR/Cas9 System | For precise gene editing in functional studies of VUS. | CRISPR/Cas9 plasmids and reagents [41] |

Emerging Technologies and Future Directions

The field of hereditary cancer diagnostics is rapidly evolving. The development of cell-free RNA (cfRNA) blood tests shows promise for non-invasive detection of cancers and mechanisms of treatment resistance by analyzing messenger RNA signals from multiple tissues [42]. Furthermore, the distinction between precision cancer medicine (often genomics-guided stratified medicine) and true personalized cancer medicine (integrating multi-omics, pharmacogenomics, and patient-specific factors) is shaping clinical trial design and future biomarker discovery [43]. Efforts to reclassify variants of uncertain significance (VUS), as demonstrated by the BRCA2 functional study, are critical for reducing uncertainty in clinical management and disparities, particularly among understudied populations like Black women who have a higher frequency of VUS [41].

Companion diagnostics (CDx) are essential tools in modern oncology, providing the critical link between a specific therapeutic product and a patient's unique biomarker status. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) defines these in vitro diagnostic devices as providing information that is critical for the safe and effective use of corresponding targeted therapies [44]. Their primary functions include identifying patients most likely to benefit from a particular treatment, identifying those at increased risk for serious side effects, and monitoring treatment response [44]. The success of this drug-diagnostic co-development model was established in 1998 with the parallel approval of trastuzumab (Herceptin) and the HercepTest for HER2-positive breast cancer, without which the targeted therapy might have been discarded due to insufficient activity in an unselected patient population [44]. This model has since become the standard for precision medicine, with the FDA having approved more than 78 drug/CDx combinations by early 2025 [45].

The molecular heterogeneity of cancer, particularly non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), necessitates precise biomarker testing to guide therapy selection. Biomarkers such as EGFR, ALK, BRAF, PD-L1, and MSI-H represent distinct molecular subtypes that predict response to specific targeted therapies and immunotherapies. The consistent upward trend in FDA approvals of new molecular entities linked to CDx assays—increasing from a mean of 3.5 annually (1998-2010) to 12.2 annually (2011-2024)—underscores the rapidly expanding role of companion diagnostics in oncology [45]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of CDx approaches for these five critical biomarkers, offering researchers and drug development professionals detailed experimental protocols, performance data, and technical insights to inform diagnostic development and clinical research strategies.

The following biomarkers guide treatment decisions across multiple cancer types, with particular significance in NSCLC:

- EGFR: Mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) gene, particularly exon 19 deletions and L858R substitutions, drive a subset of NSCLC and are targeted by EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) [46].

- ALK: Gene rearrangements (fusions) involving the anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) gene occur in approximately 3-5% of NSCLC patients and confer sensitivity to ALK inhibitors [47] [48]. ALK-positive patients often have a distinct clinical profile, frequently being younger, never-smokers or light smokers, and at higher risk of developing brain metastases [48].

- BRAF: The BRAF V600E mutation is a rare biomarker (1-2% prevalence in NSCLC) that results in constitutive activation of the MAPK pathway and is targeted by BRAF/MEK inhibitor combinations [46].

- PD-L1: Protein expression of programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) on tumor and/or immune cells is used to predict response to immune checkpoint inhibitors, with cutoff values (e.g., ≥1%, ≥50%) varying by specific therapeutic agent and cancer type [49].

- MSI-H: Microsatellite instability-high (MSI-H) status, resulting from deficient DNA mismatch repair (dMMR), is a pan-cancer biomarker predicting response to immunotherapy across multiple solid tumor types, including colorectal cancer [50].

Table 1: Clinical Significance of Key Biomarkers in Targeted Therapy and Immunotherapy

| Biomarker | Alteration Type | Primary Cancer Types | Prevalence in NSCLC | Targeted Therapies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EGFR | Mutation | NSCLC, CRC | 24-60% (for specific EGFR alterations) [46] | Osimertinib, Gefitinib, Erlotinib |

| ALK | Rearrangement/Fusion | NSCLC | 3-13% [46] | Alectinib, Crizotinib, Lorlatinib |

| BRAF | V600E Mutation | NSCLC, Melanoma, CRC | 1-2% [46] | Dabrafenib + Trametinib, Vemurafenib |

| PD-L1 | Protein Expression | NSCLC, Melanoma, Urothelial Carcinoma | Varies by cutoff | Pembrolizumab, Atezolizumab, Durvalumab |

| MSI-H | Genomic Instability | CRC, Endometrial, Pan-Cancer | <5% (across all cancer types) | Pembrolizumab, Nivolumab ± Ipilimumab |

Comparison of Diagnostic Methodologies and Platforms

Multiple technology platforms are utilized for companion diagnostic testing, each with distinct advantages, limitations, and appropriate clinical contexts. The evolution of CDx technologies has progressed from predominantly immunohistochemistry (IHC) and in situ hybridization (ISH) methods to include polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based platforms, which now represent the largest proportion of assays, and next-generation sequencing (NGS) [44].

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) detects protein expression using antibody-based staining and is widely used for PD-L1 and ALK testing. The Dako PD-L1 IHC 22C3 pharmDx (Agilent) is a prominent example, dominating the market with an estimated 50.4% share in 2025, largely due to its role as a companion diagnostic for pembrolizumab [51]. IHC offers the advantage of visualizing protein expression in the context of tissue architecture but is semi-quantitative and subject to interpretive variability.

Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) enables massive parallel sequencing of DNA or RNA, allowing comprehensive genomic profiling of multiple genes simultaneously from limited tissue samples. NGS is particularly valuable for detecting a wide range of alterations, including mutations, fusions, and insertions/deletions. Foundation Medicine's CDx assays represent this category, with some approved as group CDx for multiple therapies [44].

PCR-based methods detect specific DNA sequences with high sensitivity and are commonly used for EGFR and BRAF mutation testing. The Idylla CDx MSI Test (Biocartis) exemplifies a fully automated, cartridge-based "sample-to-result" PCR system that can deliver results in less than 3 hours with minimal hands-on time [50].

Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (FISH) detects gene rearrangements and amplifications using fluorescently labeled DNA probes and was historically the gold standard for ALK fusion detection, though it has largely been supplemented by IHC and NGS in many settings [47].

Table 2: Comparison of Companion Diagnostic Platforms and Technologies

| Technology Platform | Detects | Biomarker Examples | Key CDx Examples | Turnaround Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immunohistochemistry (IHC) | Protein Expression | PD-L1, ALK | Dako PD-L1 IHC 22C3 pharmDx, VENTANA PD-L1 (SP142) Assay [51] | 1-2 days |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) | Mutations, Fusions, CNAs, TMB | EGFR, ALK, BRAF, MSI-H | FoundationOne CDx, Guardant360 CDx | 7-14 days |

| PCR-based Methods | Mutations, MSI-H | EGFR, BRAF, MSI-H | Idylla CDx MSI Test [50], cobas EGFR Mutation Test v2 | 1-3 days |

| Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (FISH) | Gene Rearrangements, Amplifications | ALK, ROS1 | Vysis ALK Break Apart FISH Probe | 3-5 days |

Analytical and Clinical Performance Data

Companion diagnostic validation requires robust demonstration of both analytical and clinical performance. For rare biomarkers, limited sample availability poses unique challenges, often necessitating regulatory flexibility in validation strategies. A review of FDA approvals for NSCLC CDx revealed that alternative sample sources (archival specimens, retrospective samples, commercially acquired specimens) were frequently used when clinical trial samples were limited—particularly for the rarest biomarkers (100% for biomarkers with 1-2% prevalence vs. 40% for more common biomarkers) [46].

Diagnostic Performance for Rare Biomarkers

Bridging studies are critical for CDx validation, especially when the pivotal clinical trial used different assays for patient selection. Analysis of these studies shows that sample sizes vary significantly based on biomarker prevalence. For the rarest biomarkers (ROS1, BRAF V600E), bridging studies included a median of only 67 positive samples (range: 25-167) and 119 negative samples (range: 114-135), whereas more common biomarkers (EGFR mutations, PD-L1) utilized substantially larger sample sizes (median 182.5 positive samples, range: 72-282) [46].

Recent advances in deep learning approaches show promise for improving rare biomarker detection. One study utilizing vision transformer models on H&E-stained whole slide images achieved ROC AUCs of 0.85 for ROS1 and 0.84 for ALK fusion prediction in NSCLC, despite limited positive sample sizes (306 ROS1-positive and 697 ALK-positive cases out of 33,014 patients) [47]. To address the challenge of limited ROS1-positive cases, researchers implemented a two-stage training strategy: first training the model to detect a composite biomarker (ROS1, ALK, and NTRK fusions), then fine-tuning it specifically for ROS1 prediction, which enhanced performance compared to direct training (ROC AUC of 0.86 vs. 0.83) [47].

Clinical Trial Data and Survival Outcomes

The critical importance of companion diagnostics is demonstrated by clinical trial data linking biomarker status to therapeutic outcomes:

ALK Testing and Alectinib: In the phase 3 ALEX trial, first-line alectinib demonstrated a clinically meaningful overall survival benefit compared to crizotinib in advanced ALK-positive NSCLC, with 50% of patients alive at 5 years—one of the longest survival rates reported for stage IV NSCLC [52]. For patients with CNS metastases who had received prior brain radiation, the median OS was 92.0 months with alectinib versus 39.5 months with crizotinib (HR, 0.62) [52].

MSI-H Testing and Immunotherapy: The CheckMate 8HW trial established the efficacy of nivolumab plus ipilimumab in patients with MSI-H/dMMR metastatic colorectal cancer, leading to FDA approval of the Idylla CDx MSI Test as a companion diagnostic [50]. This fully automated, cartridge-based test detects a panel of 7 monomorphic biomarkers indicative of MSI and delivers results in less than 3 hours with minimal hands-on time [50].