Navigating Analytical Validation for Cancer Biomarker Assays: A Fit-for-Purpose Roadmap from Bench to Bedside

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the analytical validation of cancer biomarker assays, a critical step for translating discoveries into reliable clinical and research tools.

Navigating Analytical Validation for Cancer Biomarker Assays: A Fit-for-Purpose Roadmap from Bench to Bedside

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the analytical validation of cancer biomarker assays, a critical step for translating discoveries into reliable clinical and research tools. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational principles of validation, explores established and emerging methodological platforms like mass spectrometry and immunoassays, and addresses common troubleshooting challenges. A central theme is the 'fit-for-purpose' approach, which tailors validation stringency to the assay's intended use, from exploratory research to clinical decision-making. The content also synthesizes key performance parameters and regulatory considerations, offering a practical framework for developing robust, reproducible, and clinically impactful biomarker assays.

Laying the Groundwork: Principles and Purpose of Biomarker Validation

Analytical validation serves as the critical bridge between biomarker discovery and clinical application, providing the rigorous evidence that an assay reliably measures what it claims to measure. This comprehensive guide examines the foundational principles, key performance parameters, and experimental protocols that underpin robust analytical validation for cancer biomarker assays. We compare leading technological platforms—including immunoassays, mass spectrometry, and quantitative PCR—through structured data tables and experimental workflows. By establishing standardized frameworks for validation, the scientific community can ensure that biomarker data generated in research settings translates effectively to clinical decision-making, ultimately accelerating the development of precision oncology therapies.

The journey of a biomarker from initial discovery to clinical implementation follows a structured pipeline characterized by progressively increasing evidence requirements. Within this pathway, analytical validation constitutes the essential second phase, following discovery and preceding clinical validation [1]. This stage provides objective evidence that a biomarker assay consistently performs according to its specified technical parameters, establishing a foundation of reliability upon which all subsequent clinical interpretations will be built [2] [3].

The fit-for-purpose approach guides modern analytical validation, recognizing that the extent of validation should align with the biomarker's intended application and stage of development [3]. For biomarkers advancing toward clinical use, validation must demonstrate that the assay method accurately and precisely measures the analyte of interest in biologically relevant matrices [2]. This process stands distinct from clinical validation, which establishes the relationship between the biomarker measurement and clinical endpoints [3] [4]. Without rigorous analytical validation, even the most promising biomarker candidates risk generating irreproducible or misleading data, potentially derailing drug development programs and compromising patient care.

Core Principles and Framework of Analytical Validation

The V3 Framework: Verification, Analytical Validation, and Clinical Validation

A comprehensive framework for evaluating biomarker tests and Biometric Monitoring Technologies (BioMeTs) comprises three distinct but interconnected components: verification, analytical validation, and clinical validation (V3) [4]. Within this structure, analytical validation specifically "occurs at the intersection of engineering and clinical expertize" and focuses on evaluating "data processing algorithms that convert sample-level sensor measurements into physiological metrics" [4]. This stage typically occurs after technical verification of hardware components and before clinical validation in patient populations.

The fundamental question addressed during analytical validation is: "Does the assay accurately and reliably measure the biomarker in the intended biological matrix?" [2]. Answering this question requires systematic assessment of multiple performance characteristics under conditions that closely mimic the intended clinical or research use.

Key Performance Parameters in Analytical Validation

Table 1: Essential Performance Parameters for Analytical Validation

| Parameter | Definition | Experimental Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Precision | The closeness of agreement between independent test results obtained under stipulated conditions [2] | Repeated measurements of the same sample under specified conditions (within-run, between-day, between-laboratory) |

| Trueness | The closeness of agreement between the average value obtained from a large series of test results and an accepted reference value [2] | Comparison of measured values to reference materials or standardized methods |

| Limits of Quantification | The highest and lowest concentrations of analyte that can be reliably measured with acceptable precision and accuracy [2] [5] | Analysis of dilution series to determine the range where linearity, precision, and accuracy are maintained |

| Selectivity | The ability of the bioanalytical method to measure and differentiate the analytes in the presence of components that may be expected to be present [2] | Testing interference from related compounds, metabolites, or matrix components |

| Robustness | The ability of a method to remain unaffected by small variations in method parameters [2] | Deliberate variations in critical parameters (incubation times, temperatures, reagent lots) |

| Sample Stability | The chemical stability of an analyte in a given matrix under specific conditions for given time intervals [2] | Measurement of analyte recovery after exposure to different storage conditions |

The validation process must also establish additional parameters including dilutional linearity (ability to obtain reliable results after sample dilution), parallelism (comparable behavior in calibrators versus biological matrix), and recovery (detector response for analyte added to biological matrix compared to true concentration) [2].

Comparative Analysis of Analytical Platforms

Immunoassay Platforms

Immunoassays, particularly enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs), remain widely used for protein biomarker quantification due to their sensitivity, specificity, and relatively low implementation complexity [2] [6]. However, significant variability exists between commercial immunoassay kits, even when measuring the same analyte in identical samples.

Table 2: Comparison of Commercial ELISA Kits for Corticosterone Measurement

| ELISA Kit | Mean Corticosterone (ng/mL) | Standard Deviation | Significant Differences |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arbor Assays K014-H1 | 357.75 | ± 210.52 | Significantly higher than DRG-5186 and Enzo kits |

| DRG EIA-4164 | 183.48 | ± 108.02 | Significantly higher than DRG-5186 and Enzo kits |

| Enzo ADI-900-097 | 66.27 | ± 51.48 | No significant difference from DRG-5186 |

| DRG EIA-5186 | 40.25 | ± 39.81 | No significant difference from Enzo kit |

A comparative study of four commercial ELISA kits for corticosterone measurement revealed striking differences in absolute quantification, with the Arbor Assays kit reporting values approximately 9-fold higher than the DRG-5186 kit despite analyzing identical serum samples [6]. While correlation between kits remained high, these findings highlight that absolute concentration values cannot be directly compared across different immunoassay platforms without established standardization.

Mass Spectrometry-Based Platforms

Mass spectrometry (MS) offers advantages for biomarker verification and validation through its high specificity, multiplexing capability, and ability to distinguish between closely related molecular species [1] [7]. The transition from discovery to validation in MS-based proteomics typically involves moving from non-targeted "shotgun" approaches to targeted methods like multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) or selected reaction monitoring (SRM) [1].

Key considerations for analytical validation of MS-based biomarker assays include:

- Specificity: Demonstration that the assay measures the intended analyte without interference from isobaric compounds or matrix components [7]

- Dynamic range: The range of analyte concentrations over which the assay provides precise and accurate measurements, typically exceeding 3 orders of magnitude for MRM assays [1]

- Sample preparation robustness: Consistency of results across different sample preparation batches and operators [7]

Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) platforms have demonstrated capability for quantitative measurement of proteins at low picogram per milliliter levels in human plasma/serum, making them suitable for validating candidate biomarkers initially identified in discovery proteomics [7].

Quantitative PCR Platforms

Quantitative PCR (qPCR) represents the gold standard for nucleic acid-based biomarker measurement, with applications including gene expression analysis, mutation detection, and viral load quantification [8] [5]. Analytical validation of qPCR assays requires establishing several key parameters.

Table 3: Essential Validation Parameters for qPCR Assays

| Parameter | Definition | Best Practices |

|---|---|---|

| Limit of Detection | The lowest amount of analyte that can be detected with stated probability [5] | Determined through serial dilution of standard material; distinct from limit of quantification |

| Limit of Quantification | The lowest amount of analyte that can be quantitatively determined with acceptable precision and accuracy [5] | The point at which Ct values maintain linearity with input template concentration |

| Precision | Agreement between independent test results under stipulated conditions [5] | Assessment of both repeatability (intra-assay) and reproducibility (inter-assay) |

| Dynamic Range | The range of template concentrations over which the assay provides reliable quantification | Typically determined through analysis of serial dilutions spanning 6-8 orders of magnitude |

Advanced statistical approaches for qPCR data analysis include weighted linear regression and mixed effects models, which have demonstrated superior performance compared to simple linear regression, particularly when applied to data preprocessed using the "taking-the-difference" approach [8].

Experimental Protocols for Key Validation Parameters

Protocol for Precision Assessment

Purpose: To determine the closeness of agreement between independent test results obtained under stipulated conditions [2].

Materials:

- Quality control samples at low, medium, and high concentrations within the assay dynamic range

- Appropriate biological matrix matching intended sample type

- Full complement of reagents, standards, and equipment specified in assay protocol

Procedure:

- Prepare quality control samples in appropriate matrix at three concentrations (low, medium, high)

- For within-run precision: Analyze each QC sample in replicates (n≥5) within a single assay run

- For between-run precision: Analyze each QC sample in duplicate across multiple independent runs (n≥5 runs over different days)

- For between-laboratory precision: Coordinate with collaborating laboratories to analyze identical QC samples using standardized protocols

Calculation: Calculate the mean, standard deviation (SD), and coefficient of variation (CV% = [SD/mean] × 100) for each QC level at each precision level. Acceptable precision is typically defined as CV% <15-20%, though more stringent criteria may apply for biomarkers with narrow therapeutic windows [2].

Protocol for Determination of Limits of Quantification

Purpose: To establish the lowest and highest concentrations of analyte that can be measured with acceptable precision and accuracy [2] [5].

Materials:

- Stock solution of analyte with known concentration

- Appropriate biological matrix (stripped or surrogate if necessary)

- Standard materials for calibration curve

Procedure:

- Prepare serial dilutions of the analyte in appropriate matrix covering the expected range

- Analyze each dilution in multiple replicates (n≥5) across independent runs

- For the lower limit of quantification (LLOQ): Identify the lowest concentration where CV% ≤20% and accuracy is within ±20% of nominal value

- For the upper limit of quantification (ULOQ): Identify the highest concentration where CV% ≤20% and accuracy is within ±20% of nominal value

- Confirm that the calibration curve demonstrates linearity (R² > 0.99) across the range from LLOQ to ULOQ

Documentation: Report the determined LLOQ and ULOQ values, along with supporting precision and accuracy data at these concentration levels. For qPCR assays, the limit of quantification represents "the lowest dilution that maintains linearity" between Ct values and template concentration [5].

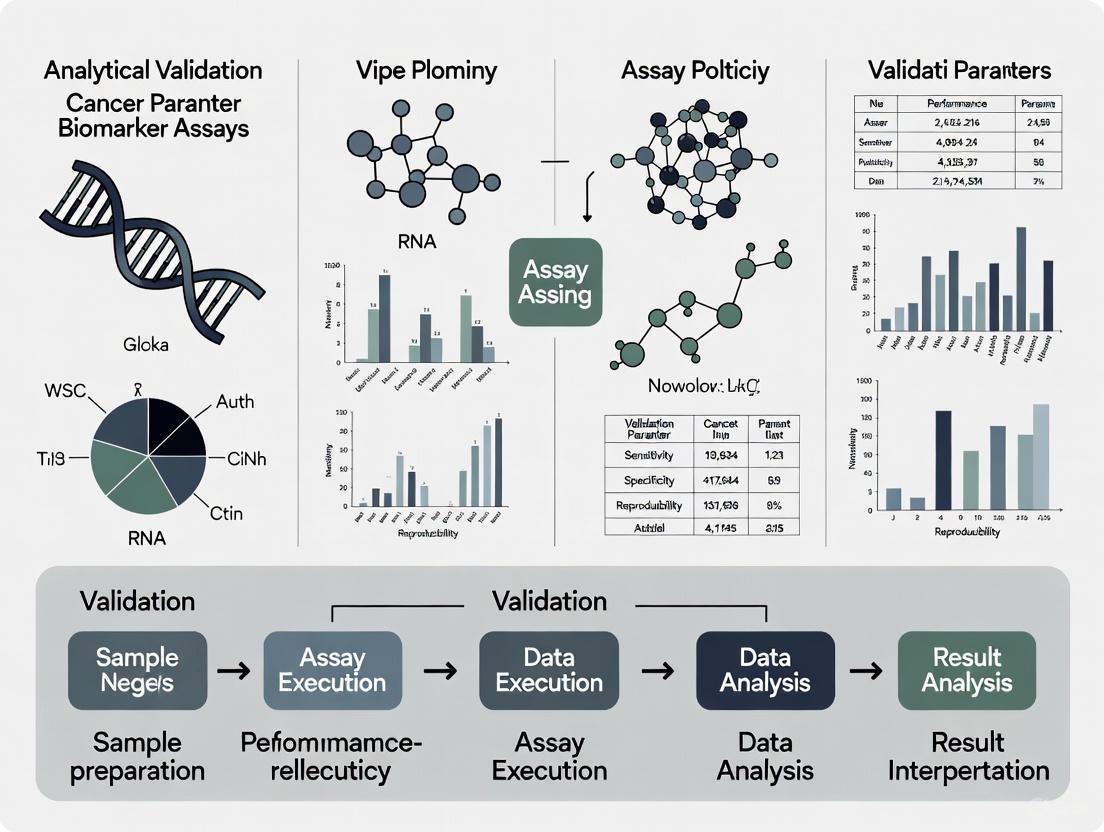

Visualizing the Analytical Validation Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for analytical validation of biomarker assays, integrating multiple performance parameters into a systematic evaluation process:

Analytical Validation Parameter Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Analytical Validation

| Reagent/Material | Function in Validation | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Standards | Provide benchmark for accuracy assessment and calibration | Should be of highest available purity with documented provenance [2] |

| Quality Control Materials | Monitor assay performance across validation experiments | Should include low, medium, and high concentrations in appropriate matrix [6] |

| Biological Matrix | Evaluate assay performance in relevant sample type | Should match intended sample matrix (serum, plasma, tissue homogenate) [2] |

| Assay Diluents | Maintain analyte stability and matrix compatibility | Should be validated for absence of interference with assay performance [2] |

| Interference Compounds | Test assay selectivity against structurally similar compounds | Should include metabolites, related biomarkers, and common medications [2] |

Analytical validation represents the indispensable bridge between biomarker discovery and clinical utility, providing the evidentiary foundation that an assay generates reliable, reproducible data. As demonstrated through comparative analysis of major analytical platforms, each technology presents distinct advantages and validation considerations. Immunoassays offer practical implementation but may show significant inter-kit variability [6]. Mass spectrometry provides exceptional specificity but requires specialized expertise [1] [7]. Quantitative PCR delivers exceptional sensitivity for nucleic acid detection but demands rigorous statistical approaches for data analysis [8] [5].

The experimental protocols and frameworks presented herein provide researchers with practical guidance for implementing comprehensive analytical validation strategies. By adopting a fit-for-purpose approach that aligns validation rigor with intended application, the scientific community can advance robust biomarker assays along the development pipeline. Ultimately, rigorous analytical validation accelerates the translation of promising biomarkers from research discoveries to clinically impactful tools, strengthening the foundation of precision oncology and therapeutic development.

The development and integration of robust cancer biomarkers are fundamental to the advancement of precision oncology. However, the journey from biomarker discovery to clinical implementation is notoriously challenging, with an estimated success rate of only 0.1% for clinical translation [9]. A primary reason for this high attrition rate is not necessarily flawed science, but often poor choice of assay and inadequate method validation [10] [11]. To address this challenge, the fit-for-purpose paradigm has emerged as a practical and rigorous framework for biomarker method validation. This approach stipulates that the level of validation rigor should be commensurate with the intended use of the biomarker data and the associated regulatory requirements [10] [12] [13].

The core principle of fit-for-purpose validation is that the "purpose" or Context of Use (COU) is the primary driver for designing the validation process [12]. The COU defines the specific role of the biomarker in drug development or clinical decision-making, which can range from exploratory research to use as a companion diagnostic that dictates therapeutic choice. This paradigm fosters a flexible yet scientifically sound approach, allowing for iterative validation where the assay can be re-validated with increased rigor if its intended use evolves during the drug development process [12] [13]. Understanding this paradigm is essential for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals aiming to efficiently translate biomarker science into clinically useful tools.

The Spectrum of Biomarker Applications and Corresponding Validation Requirements

Classifying Biomarker Assays and Their Context of Use

Biomarkers in oncology serve diverse functions, and their application dictates the necessary level of analytical validation. The American Association of Pharmaceutical Scientists (AAPS) and the US Clinical Ligand Society have identified five general classes of biomarker assays, each with distinct validation requirements [10]. A critical distinction lies between prognostic biomarkers, which provide information about the overall cancer course irrespective of therapy, and predictive biomarkers, which forecast response to a specific therapeutic intervention [14] [15]. Predictive biomarkers, such as EGFR mutations predicting response to gefitinib in lung cancer, are typically identified through an interaction test between treatment and biomarker in a randomized clinical trial [14].

The clinical application of a biomarker spans a wide spectrum. On one end are exploratory biomarkers used for internal decision-making in early research, which require a lower validation stringency. On the opposite end are companion diagnostics used to select patients for specific therapies, which demand the most rigorous validation, often culminating in FDA approval [12] [16]. For instance, the MI Cancer Seek test, an FDA-approved comprehensive molecular profiling assay, underwent extensive validation to achieve over 97% agreement with other FDA-approved diagnostics, a necessity for its role in guiding treatment [16]. The fit-for-purpose paradigm aligns the validation effort with this spectrum of application, ensuring resources are focused where they have the greatest impact on patient care and regulatory success.

A Framework for Fit-for-Purpose Validation

The process of fit-for-purpose biomarker method validation can be envisaged as progressing through discrete, iterative stages [10]. The initial stage involves defining the purpose and selecting the candidate assay, which is arguably the most critical step. Subsequent stages involve assembling reagents, writing the validation plan, the experimental phase of performance verification, and the final evaluation of fitness-for-purpose. The process continues with in-study validation to assess robustness in the clinical context and culminates in routine use with quality control monitoring. This phased approach, driven by continual improvement, ensures that the assay remains reliable for its intended application throughout its lifecycle.

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between a biomarker's clinical application and the corresponding validation rigor within the fit-for-purpose paradigm.

Experimental Protocols and Performance Standards for Biomarker Assays

Technical Validation Parameters Across Assay Categories

The specific performance parameters evaluated during biomarker method validation are directly determined by the assay's classification. Definitive quantitative assays, which use fully characterized reference standards to calculate absolute quantitative values, require the most comprehensive validation. In contrast, qualitative (categorical) assays, which rely on discrete scoring scales, have a different set of requirements [10]. The following table summarizes the consensus position on which key performance parameters should be investigated for each general class of biomarker assay.

Table 1: Key Performance Parameters for Biomarker Assay Validation by Category

| Performance Characteristic | Definitive Quantitative | Relative Quantitative | Quasi-Quantitative | Qualitative |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy / Trueness (Bias) | + | + | ||

| Precision | + | + | + | |

| Reproducibility | + | |||

| Sensitivity | + (LLOQ) | + (LLOQ) | + | + |

| Specificity | + | + | + | + |

| Dilution Linearity | + | + | ||

| Parallelism | + | + | ||

| Assay Range | + (LLOQ–ULOQ) | + (LLOQ–ULOQ) | + |

Abbreviations: LLOQ = lower limit of quantitation; ULOQ = upper limit of quantitation [10].

For definitive quantitative assays (e.g., mass spectrometric analysis), the objective is to determine unknown concentrations as accurately as possible. Performance standards often adopt a default value of 25% for precision and accuracy (30% at the LLOQ), which is more flexible than the 15-20% standard for bioanalysis of small molecules [10]. A modern statistical approach endorsed by the Societe Francaise des Sciences et Techniques Pharmaceutiques (SFSTP) involves constructing an accuracy profile. This profile accounts for total error (bias and intermediate precision) and a pre-set acceptance limit, producing a β-expectation tolerance interval that visually displays the confidence interval for future measurements. This method allows researchers to determine the percentage of future values likely to fall within the pre-defined acceptance limit [10].

Experimental Protocol for a Definitive Quantitative Assay

A typical protocol for validating a definitive quantitative biomarker assay using the accuracy profile method involves the following steps [10]:

- Calibration Standards and Validation Samples (VS): Use 3-5 different concentrations of calibration standards and 3 different concentrations of VS (representing high, medium, and low points on the calibration curve).

- Replication: Run each calibration standard and VS in triplicate on 3 separate days to capture inter-day and intra-day variability.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the bias and intermediate precision for each concentration of the VS.

- Construct Accuracy Profile: Plot the β-expectation tolerance intervals (e.g., 95%) for each concentration level against the pre-defined acceptance limits.

- Evaluation: If the tolerance intervals for all concentrations fall entirely within the acceptance limits, the method is considered valid for its intended use. Parameters such as sensitivity, dynamic range, LLOQ, and ULOQ are derived directly from this profile.

For next-generation sequencing (NGS) assays like liquid biopsies, the experimental validation focuses on different parameters. The Hedera Profiling 2 (HP2) ctDNA test, for example, was validated using reference standards and a cohort of 137 clinical samples pre-characterized by orthogonal methods. In reference standards with variants at 0.5% allele frequency, the assay demonstrated a sensitivity of 96.92% and specificity of 99.67% for single-nucleotide variants and insertions/deletions, and 100% for fusions [17]. This highlights how the validation protocol is adapted to the technology and its intended clinical application.

Comparative Analysis of Validated Biomarker Assays

The fit-for-purpose paradigm is best understood through real-world examples. The following table provides a comparative analysis of several biomarker assays, highlighting how their validation strategies and performance data align with their specific Contexts of Use.

Table 2: Comparative Performance Data of Validated Biomarker Assays

| Assay Name | Technology / Platform | Intended Context of Use (COU) | Key Analytical Performance Data | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hedera Profiling 2 (HP2) | Hybrid capture NGS (Liquid Biopsy) | Detection of somatic alterations in ctDNA for precision oncology | SNVs/Indels (AF 0.5%): Sens: 96.92%, Spec: 99.67%Fusions: Sens: 100%Clinical Concordance: 94% for ESMO Level I variants | [17] |

| MI Cancer Seek | Whole Exome & Whole Transcriptome Sequencing | Comprehensive molecular profiling; FDA-approved companion diagnostic | Overall Concordance: >97% with other FDA-approved CDsMSI detection: Near-perfect accuracy in colorectal/endometrial cancerMinimal Input: 50 ng DNA from FFPE | [16] |

| Definitive Quantitative Assay (Theoretical) | Ligand Binding (e.g., ELISA) or Mass Spectrometry | Accurate concentration measurement for PK/PD or efficacy endpoints | Precision/Accuracy: ±25% (±30% at LLOQ)Validation Approach: Accuracy Profile with β-expectation tolerance intervals | [10] |

| OVA1 | Multi-marker panel (5 protein biomarkers) | Risk stratification for ovarian cancer; adjunct to clinical assessment | Purpose: Aids referral of high-risk women (Not a standalone screening tool) | [18] |

This comparison demonstrates that a decentralized liquid biopsy test (HP2) achieves high sensitivity and specificity for variant detection, suitable for molecular profiling. In contrast, an FDA-approved companion diagnostic (MI Cancer Seek) must demonstrate near-perfect concordance with existing standards. A general-purpose quantitative assay follows statistical validation principles, while a diagnostic aid (OVA1) is validated for a specific clinical triage role rather than standalone screening.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful biomarker development and validation rely on a foundation of critical reagents and materials. The following table details key components of the "Scientist's Toolkit," along with their essential functions and associated challenges.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Biomarker Assay Validation

| Tool / Reagent | Function in Development & Validation | Key Considerations & Challenges |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Standard / Calibrator | Serves as the basis for creating a calibration curve and assigning quantitative values to unknowns. | A major limitation is the lack of true reference standards for many biomarkers. Recombinant protein calibrators may differ from endogenous biomarkers, necessitating the use of endogenous quality controls for stability testing [12]. |

| Quality Control (QC) Samples | Used to monitor assay performance during both validation and routine sample analysis to ensure consistency and reliability. | Endogenous QCs are preferred over recombinant material for stability studies and in-study monitoring. During validation, QC results are evaluated against pre-set acceptance criteria (e.g., the 4:6:15 rule or confidence intervals) [10] [12]. |

| Validated Antibodies / Probes | For immunohistochemistry or ligand-binding assays, these are critical for the specific detection of the target biomarker. | Antibody sensitivity and specificity must be determined in the sample matrix (e.g., FFPE tissues), not just by Western blot. Optimal positive and negative controls (e.g., cell lines with/without target expression) are required for validation [11]. |

| Characterized Biospecimens | Used for assay development, validation, and as positive/negative controls. Include patient samples, cell lines, and synthetic reference standards. | Pre-analytical variables (collection, processing, storage) significantly impact results. Specimens should be well-characterized and relevant to the target population. Using "samples of convenience" is a major source of bias [12] [11] [9]. |

| Orthogonal Assay | A method based on different principles used to verify results from the primary biomarker assay. | Used in clinical validation to establish concordance. For example, the HP2 ctDNA assay was validated against pre-characterized clinical samples and other methods [17]. |

Navigating Pre-Analytical Variables and Workflow Considerations

A critical yet often overlooked aspect of biomarker validation is the management of pre-analytical variables. These are factors that affect the sample before it is analyzed and can have a profound impact on the integrity of the biomarker and the reliability of the results [12] [11]. For tissue-based biomarkers, such as those detected by immunohistochemistry, key pre-analytical variables include the time between tissue removal and fixation (warm ischemia), the type of fixative, and the length and conditions of fixation and paraffin-embedding [11]. For liquid biopsies, variables include the type of blood collection tube, time to plasma processing, and storage conditions [12].

These variables can be categorized as controllable or uncontrollable. Controllable variables, such as the matrix, specimen collection, processing, and transport procedures, should be standardized through detailed SOPs. For example, the choice of anticoagulant in blood collection tubes can affect the measurement of certain biomarkers like VEGF [12]. Uncontrollable variables, such as patient gender, age, or co-morbidities, cannot be standardized but must be documented and accounted for during data analysis and study design [12]. The following workflow diagram outlines key pre-analytical and analytical steps where these variables must be managed to ensure data integrity.

The fit-for-purpose paradigm provides a robust, practical, and logical framework for the validation of cancer biomarker assays. By tightly aligning the rigor of analytical validation with the biomarker's Context of Use, from exploratory research to companion diagnostics, this approach ensures scientific integrity while optimizing resource allocation. The successful implementation of this paradigm requires a deep understanding of the clinical and regulatory landscape, meticulous management of pre-analytical variables, and the application of appropriate statistical methods for performance verification. As precision oncology continues to evolve, driven by technologies like NGS and liquid biopsy, adherence to the principles of fit-for-purpose validation will be paramount in translating promising biomarkers from the research bench to the clinical bedside, ultimately improving patient care and outcomes.

The development and validation of biomarker assays are fundamental to advancing precision medicine, particularly in oncology. These assays provide critical data on disease detection, prognosis, and therapeutic response, enabling more personalized treatment approaches. Classification of these assays into definitive quantitative, relative quantitative, quasi-quantitative, and qualitative categories is essential for appropriate application in both research and clinical decision-making. This systematic framework ensures that the analytical performance of an assay aligns with its intended Context of Use (COU), a concise description of a biomarker's specified application in drug development [19].

The validation requirements for biomarker assays differ significantly from those for traditional pharmacokinetic (PK) assays, necessitating a fit-for-purpose approach that considers the specific biological and technical challenges of measuring endogenous biomarkers [19]. Unlike PK assays that measure well-characterized drug compounds, biomarker assays often lack reference materials identical to the endogenous analyte and must account for substantial biological variability and pre-analytical factors that can influence results [20] [19]. This comparison guide examines the performance characteristics, experimental methodologies, and applications of different biomarker assay classes to inform their appropriate selection and validation in cancer research.

Biomarker Assay Classification Framework

Biomarker assays can be categorized based on their quantitative output and the nature of the measurements they provide. This classification system ranges from assays that deliver exact concentration values to those that provide simple categorical results, with each category serving distinct purposes in biomarker development and application.

Categories of Biomarker Assays

Definitive Quantitative Assays: These assays measure the absolute quantity of an analyte using a calibration curve with reference standards that are structurally identical to the endogenous biomarker. They provide exact numerical concentrations in appropriate units (e.g., ng/mL, nM) and require the highest level of analytical validation [19].

Relative Quantitative Assays: These assays measure the quantity of an analyte relative to a reference material that may not be structurally identical to the endogenous biomarker. While they provide numerical results, these values are relative rather than absolute and require careful interpretation within the assay's specific parameters [19].

Quasi-Quantitative Assays: These assays provide approximate numerical estimates based on non-calibrated measurements or indirect relationships. The results are typically reported in arbitrary units rather than absolute concentrations and have more limited precision compared to fully quantitative methods [19].

Qualitative Assays: These assays classify samples into discrete categories (e.g., positive/negative, mutant/wild-type) without providing numerical values. They focus on determining the presence or absence of specific biomarkers or characteristics rather than measuring quantities [19] [21].

Table 1: Biomarker Assay Classification Framework

| Assay Category | Measurement Output | Reference Standard | Data Interpretation | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Definitive Quantitative | Exact concentration with units | Identical to endogenous analyte | Direct quantitative comparison | Pharmacodynamic biomarkers, diagnostic applications |

| Relative Quantitative | Relative numerical value | Similar but not identical to analyte | Relative comparison between samples | Exploratory research, target engagement |

| Quasi-Quantitative | Approximate numerical value | Non-calibrated or indirect reference | Trend analysis within study | Screening assays, prioritization |

| Qualitative | Categorical classification | Qualitative controls | Binary or categorical assessment | Companion diagnostics, patient stratification |

Biomarker Assay Selection Workflow

Experimental Protocols for Biomarker Assay Comparison

Rigorous experimental protocols are essential for comparing biomarker assay performance across different categories. These protocols evaluate analytical parameters such as precision, accuracy, sensitivity, and reproducibility under conditions that mimic real-world applications.

Reference Sample Design for Assay Benchmarking

The experimental design for comparing biomarker assays requires carefully characterized reference materials that represent the biological and technical challenges encountered in actual study samples. A community-wide benchmarking study for DNA methylation assays utilized 32 reference samples including matched tumor/normal tissue pairs, drug-treated cell lines, titration series, and matched fresh-frozen/FFPE sample pairs to simulate diverse clinical scenarios [21]. This approach allows comprehensive evaluation of assay performance across different sample types and conditions relevant to cancer biomarker development.

For quantitative assays, establishing a calibration curve with appropriate reference standards is fundamental. However, for many biomarker assays, particularly those measuring protein biomarkers, reference materials may not be structurally identical to the endogenous analyte, necessitating additional validation steps such as parallelism assessments to demonstrate similarity between calibrators and endogenous analytes [19]. The experimental protocol must also account for pre-analytical variables including sample collection tubes, processing time, centrifugation conditions, and storage duration, as these factors contribute significantly to measurement variability [20].

Protocol for Quantitative Assay Validation

A standardized protocol for validating quantitative biomarker assays should include the following key steps:

Reference Material Characterization: Evaluate the similarity between reference standards and endogenous biomarkers through parallelism experiments where serial dilutions of biological samples are compared to the calibration curve [19].

Precision Profile Assessment: Determine within-run (repeatability) and between-run (intermediate precision) variability using quality control samples at multiple concentrations across different days [20].

Linearity of Dilution: Demonstrate that samples can be diluted to within the assay's quantitative range while maintaining proportional results [19].

Stability Studies: Evaluate analyte stability under various storage conditions (freeze-thaw cycles, benchtop stability, long-term storage) using actual study samples rather than only spiked standards [19].

Specificity and Selectivity: Assess interference from related molecules, matrix components, and common medications using samples from healthy donors and the target population [20].

Table 2: Key Experimental Parameters for Biomarker Assay Validation

| Validation Parameter | Definitive Quantitative | Relative Quantitative | Quasi-Quantitative | Qualitative |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy/Recovery | 85-115% with spike-recovery | Relative accuracy assessment | Not required | Not applicable |

| Precision (CV) | <15-20% total CV | <20-25% total CV | <30% total CV | Positive/negative agreement |

| Calibration Curve | Required with authentic standard | Required with similar standard | Optional | Not applicable |

| Parallelism Assessment | Critical for endogenous analyte | Critical for endogenous analyte | Recommended | Not applicable |

| Stability | Comprehensive evaluation | Limited evaluation | Minimal evaluation | Sample integrity only |

| Reference Range | Established with population data | Study-specific controls | Not required | Cut-off determination |

Performance Comparison of Biomarker Assay Categories

Direct comparison of different assay categories reveals distinct performance characteristics that influence their suitability for specific applications in cancer biomarker research.

Quantitative Performance Metrics

In a comprehensive comparison of DNA methylation technologies, quantitative assays including amplicon bisulfite sequencing (AmpliconBS) and bisulfite pyrosequencing (Pyroseq) demonstrated superior all-around performance for biomarker development, providing precise measurements across the dynamic range with single-CpG resolution [21]. These methods showed high sensitivity in detecting methylation differences in low-input samples and effectively discriminated between cell types, making them suitable for both discovery and clinical applications.

A study comparing quantitative and qualitative MRI metrics in primary sclerosing cholangitis found that quantitative measurements of liver stiffness (determined by magnetic resonance elastography) and spleen volume had perfect and near-perfect agreement (intraclass correlation coefficients of 1.00 and 0.9996, respectively), while qualitative ANALI scores determined by radiologists showed only moderate inter-rater agreement (kappa = 0.42-0.57) [22]. Furthermore, as a continuous variable, liver stiffness was the single best predictor of hepatic decompensation (concordance score = 0.90), demonstrating the prognostic advantage of quantitative measurements in clinical applications.

Reproducibility Across Assay Categories

Reproducibility varies significantly across assay categories, with definitive quantitative assays generally demonstrating the highest inter-laboratory consistency when properly validated. In the DNA methylation benchmarking study, most quantitative assays showed good agreement across different laboratories, though some technology-specific differences were observed [21]. The study highlighted that assay sensitivity can be influenced by CpG density and genomic context, with some methods performing better in specific genomic regions.

For qualitative assays, performance is typically measured by positive and negative agreement rather than traditional precision metrics. These assays often demonstrate high reproducibility for categorical calls but may lack the granularity needed for monitoring subtle changes in biomarker levels over time [21]. The implementation of standardized protocols, automated procedures, and appropriate quality controls can significantly improve reproducibility across all assay categories [20].

Technical Considerations for Biomarker Assay Implementation

Successful implementation of biomarker assays in cancer research requires careful attention to technical factors that influence data quality and interpretation.

Pre-analytical Variables

Pre-analytical factors represent a significant source of variability in biomarker measurements, potentially accounting for up to 75% of errors in laboratory testing [20]. These factors include sample collection methods, choice of collection tubes, processing time, centrifugation conditions, and storage parameters. For example, the type of blood collection tube and its components (including gel activators) can markedly affect results, as can inadequate fill volume compromising sample-to-anticoagulant ratios [20].

Biological variability must also be considered during assay implementation. Factors such as age, sex, diet, time of day, comorbidities, medications, and menstrual cycle stage can all influence biomarker levels [20]. Understanding these sources of variability is essential for establishing appropriate reference ranges and interpreting results in the context of individual patient factors.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Biomarker Assay Development

| Reagent/Material | Function | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Standards | Calibration and quality control | May differ from endogenous analyte in structure, folding, glycosylation [19] |

| Quality Control Materials | Monitoring assay performance | Should mimic study samples; may use pooled patient samples [20] |

| Collection Tubes | Sample acquisition and stabilization | Tube type and additives can affect results; consistency is critical [20] |

| Assay Antibodies | Detection and capture reagents | Specificity must be demonstrated; up to 50% of commercial antibodies may fail [20] |

| Matrix Materials | Diluent and background assessment | Should match study sample matrix; assess interference [19] |

| Enzymes and Conversion Reagents | Sample processing and modification | Batch-to-batch variability must be monitored [21] |

Regulatory and Validation Considerations

The fit-for-purpose approach to biomarker assay validation recognizes that the extent of validation should be appropriate for the intended context of use [19]. The 2025 FDA Bioanalytical Method Validation for Biomarkers guidance acknowledges that biomarker assays differ fundamentally from PK assays and require different validation strategies [19]. Unlike PK assays that typically use a fully characterized reference standard identical to the drug analyte, biomarker assays often rely on reference materials that may differ from the endogenous analyte in critical characteristics such as molecular structure, folding, truncation, and post-translational modifications [19].

This fundamental difference means that validation parameters for biomarker assays must focus on demonstrating performance with endogenous analytes rather than solely through spike-recovery experiments. Key assessments should include parallelism testing to evaluate similarity between calibrators and endogenous biomarkers, and use of endogenous quality controls that more adequately characterize assay performance with actual study samples [19].

The classification of biomarker assays into definitive quantitative, relative quantitative, quasi-quantitative, and qualitative categories provides a critical framework for selecting appropriate methodologies for specific research and clinical applications in oncology. Quantitative assays generally offer superior performance for monitoring disease progression and treatment response, while qualitative assays provide practical solutions for patient stratification and companion diagnostics. The emerging regulatory consensus emphasizes a fit-for-purpose validation approach that addresses the unique challenges of biomarker measurements, particularly the frequent lack of reference materials identical to endogenous analytes. As cancer biomarker research continues to evolve, this classification system and the associated validation strategies will support the development of robust, reproducible assays that generate reliable data for precision medicine applications.

Regulatory Landscape and Key Guidelines for Clinical Trial Assays

The regulatory landscape for clinical trial assays is dynamic, with recent updates emphasizing fit-for-purpose validation, the integration of advanced technologies like artificial intelligence (AI), and flexible approaches for novel biomarker development. These assays, which are critical for measuring biomarkers in drug development, are subject to guidance from various global health authorities, including the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the European Medicines Agency (EMA), and the International Council for Harmonisation (ICH). A foundational understanding of Context of Use (COU) is paramount, as it defines the specific purpose an assay is intended to serve in the drug development process and directly dictates the extent and nature of its validation [19]. Unlike pharmacokinetic (PK) assays that measure drug concentrations, biomarker assays present unique challenges, often lacking a fully characterized reference standard identical to the endogenous analyte, which necessitates different validation strategies [19].

Recent regulatory activity has been significant. The FDA's finalization of the ICH E6(R3) guideline for Good Clinical Practice introduces more flexible, risk-based approaches to clinical trial conduct [23]. Furthermore, the start of 2025 saw the FDA release the Bioanalytical Method Validation for Biomarkers (BMVB) guidance, a pivotal document that officially recognizes the distinct nature of biomarker assay validation while creating some ambiguity by referencing ICH M10, a guideline developed for PK assays [24] [19]. Concurrently, professional societies are stepping forward to provide specialized guidance, such as the European Society for Medical Oncology's (ESMO) first framework for AI-based biomarkers in cancer, which categorizes these novel tools based on risk and required evidence levels [25]. These developments collectively shape the requirements for robust analytical validation of clinical trial assays, particularly in complex fields like cancer biomarker research.

Major Global Regulatory Guidelines

Navigating the requirements of various regulatory bodies is essential for the successful development and validation of clinical trial assays. The following table summarizes the key recent guidelines and their implications for assay development.

Table 1: Key Global Regulatory Guidelines for Clinical Trial Assays (2024-2025)

| Health Authority | Guideline Name | Status & Date | Key Focus & Impact on Assays |

|---|---|---|---|

| FDA (U.S.) | ICH E6(R3): Good Clinical Practice | Final (Sep 2025) [23] | Introduces flexible, risk-based approaches for trial conduct, impacting how assays are integrated and monitored within clinical trials. |

| FDA (U.S.) | Bioanalytical Method Validation for Biomarkers (BMVB) | Final (Jan 2025) [24] [19] | Recognizes differences from PK assays; recommends a fit-for-purpose approach and ICH M10 as a starting point, but requires justification for deviations. |

| EMA (EU) | Reflection Paper on Patient Experience Data | Draft (Sep 2025) [23] | Encourages inclusion of patient-reported data in medicine development, which may influence the development of companion diagnostics. |

| ESMO | Basic Requirements for AI-based Biomarkers in Oncology (EBAI) | Published (Nov 2025) [25] | Provides a validation framework for AI biomarkers, categorizing them by risk (Classes A-C) and defining required evidence for clinical use. |

| Friends of Cancer Research | Analysis on CDx for Rare Biomarkers | Published (2025) [26] | Characterizes regulatory flexibilities, such as use of alternative sample sources, for validating companion diagnostics for rare cancer biomarkers. |

Detailed Analysis of FDA Biomarker Guidance (BMVB)

The FDA's BMVB guidance, finalized in January 2025, marks a critical step by formally distinguishing biomarker validation from PK assay validation [19]. This guidance officially retires the relevant section of the 2018 FDA BMV guidance and establishes that a "fit-for-purpose" approach should be used to determine the appropriate extent of method validation [24] [19]. However, it has also sparked discussion within the bioanalytical community because it directs sponsors to ICH M10 as a starting point, despite ICH M10 explicitly stating it does not apply to biomarkers [24].

This creates a nuanced position for sponsors: while the principles of ICH M10 (e.g., assessing accuracy, precision, sensitivity) are relevant, the techniques to evaluate them must be adapted. For instance, unlike PK assays that use a well-defined drug reference standard, biomarker assays often rely on surrogate materials (e.g., recombinant proteins) that may not perfectly match the endogenous analyte's structure or modifications [19]. Therefore, key validation parameters like accuracy and parallelism must be assessed using samples containing the endogenous biomarker, rather than solely through spike-recovery of the reference standard [19]. The guidance ultimately requires sponsors to scientifically justify their chosen validation approach, particularly when it differs from the ICH M10 framework, in their method validation reports [19].

Emerging Guidance for AI-Based Biomarkers

The ESMO EBAI framework addresses the growing field of AI-based biomarkers, which use complex algorithms to analyze multidimensional data (e.g., histology slides) to predict disease features or treatment response [25]. This guidance establishes three risk-based categories:

- Class A (Low Risk): Automates tedious tasks (e.g., cell counting).

- Class B (Medium Risk): Acts as a surrogate biomarker for screening or enrichment within a population. It requires strong evidence of high sensitivity and specificity.

- Class C (High Risk): Comprises novel biomarkers without an established counterpart. This class is subdivided into C1 (prognostic) and C2 (predictive), with C2 requiring the highest level of evidence, ideally from randomized clinical trials [25].

For all classes, the framework emphasizes clarity on the ground truth (the gold standard for comparison), transparent reporting of performance against that standard, and demonstration of generalisability across different clinical settings and data sources [25].

Experimental Protocols and Validation Parameters

A robust analytical validation is the cornerstone of any clinical trial assay, ensuring the data generated is reliable and fit for its intended purpose. The specific protocols and acceptance criteria are driven by the assay's Context of Use (COU).

Core Validation Parameters and Methodologies

The following table outlines standard experimental protocols for key analytical validation parameters, drawing from established clinical and laboratory standards.

Table 2: Key Analytical Validation Parameters and Experimental Protocols

| Validation Parameter | Experimental Protocol Summary | Key Acceptance Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Limit of Blank (LoB) & Limit of Detection (LoD) | Follows CLSI EP17-A2. Test blank and low-concentration samples over multiple days (e.g., 30 measurements each) to determine the lowest analyte level distinguishable from blank and reliably detected, respectively [27]. | LoD is typically set at a concentration where the signal-to-noise ratio is significantly distinguished. |

| Limit of Quantitation (LoQ) | Follows CLSI EP17-A2. Test serially diluted samples to find the lowest concentration measurable with defined precision (e.g., ≤20% coefficient of variation) [27]. | CV ≤ 20% at the LoQ concentration [27]. |

| Precision | Analyze multiple replicates of quality control samples at various concentrations (low, medium, high) within and across multiple runs/days [27]. | Pre-defined CV targets based on COU (e.g., <10% CV for high-sensitivity troponin at the 99th percentile URL) [27]. |

| Analytical Measurement Range (AMR) | Follows CLSI EP6-A. Perform linearity testing by serially diluting a high-concentration sample and plotting measured vs. expected values [27]. | High coefficient of determination (R²) demonstrating linearity across the claimed range. |

| Parallelism | Assessed by serially diluting patient samples containing the endogenous biomarker and comparing the dose-response curve to that of the calibrator [19]. | Demonstration that the diluted patient samples behave similarly to the standard curve, indicating no matrix interference. |

The workflow below illustrates the logical relationship and sequence of these key validation experiments.

Assessing Clinical Performance

Once analytical validation is established, clinical performance must be assessed. This involves determining the assay's diagnostic sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values in a relevant patient population. A study on high-sensitivity troponin I (hs-cTnI) assays provides a template for such an evaluation, comparing strategies like the Limit of Detection (LoD) strategy (offering 100% sensitivity but low positive predictive value) and the more balanced 0/2-hour algorithm [27]. For companion diagnostics, especially for rare biomarkers, regulatory flexibilities may be employed. A recent analysis of CDx for non-small cell lung cancer highlighted the use of alternative sample sources and bridging studies with smaller sample sizes to overcome the challenge of limited clinical specimens for the rarest biomarkers [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The successful development and validation of a clinical trial assay rely on a suite of critical reagents and materials. The selection and characterization of these components are vital for ensuring assay robustness and reproducibility.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Biomarker Assay Development

| Tool / Reagent | Function & Importance |

|---|---|

| Reference Standard / Calibrator | Used to create the standard curve for quantitation. A major challenge is that these are often recombinant proteins or synthetic peptides that may not be identical to the endogenous biomarker, necessitating parallelism testing [19]. |

| Quality Control (QC) Samples | Materials with known analyte concentrations (often in a surrogate matrix) used to monitor assay precision and accuracy within and across runs [27]. |

| Characterized Biobanked Samples | Well-annotated clinical samples from patients and healthy donors. Crucial for determining clinical cut-offs, assessing specificity, and performing parallelism experiments with the endogenous biomarker [19] [27]. |

| Surrogate Matrix | A modified or artificial matrix (e.g., buffer, stripped serum) used to prepare calibrators and QCs when the native biological matrix interferes with the assay. Performance must be bridged to the native matrix [19]. |

| Critical Assay Reagents | Antibodies, primers, probes, enzymes, and other core components that define the assay's specificity and sensitivity. These require rigorous lot-to-lot testing [27]. |

Regulatory Pathways and Strategic Considerations

Navigating the regulatory landscape requires a strategic approach from assay developers and sponsors. The following diagram outlines a high-level decision-making pathway for validating a clinical trial assay, incorporating key regulatory considerations.

Key Strategic Implications

- Early Regulatory Interaction is Critical: For assays where the data will support a regulatory decision for drug approval or labeling, early consultation with agencies is strongly recommended. This is especially important for novel technologies or when validation presents unique challenges [19].

- Embrace Fit-for-Purpose and Flexibility: The

fit-for-purposeprinciple is now enshrined in FDA guidance [19]. Furthermore, regulatory flexibilities exist for challenging situations, such as developing companion diagnostics for rare biomarkers, where alternative sample types and smaller bridging studies may be acceptable [26]. - Discontinue "Qualification" in Favor of "Validation": To align with FDA terminology and avoid confusion with the separate process of "biomarker qualification," the term

"fit-for-purpose validation"or simply"validation"should be used for assays, discontinuing the use of "qualification" in this context [19].

The regulatory landscape for clinical trial assays in 2025 is characterized by a welcome recognition of their unique challenges, as seen in the FDA's new BMVB guidance and ESMO's framework for AI-based biomarkers. The core principles of fit-for-purpose validation, context of use, and scientific justification are more critical than ever. Success in this environment depends on a deep understanding of both the technical requirements for robust analytical validation and the strategic regulatory pathways available. As the field advances with more complex biomarkers and AI-driven tools, ongoing dialogue between industry and regulators will be essential to maintain scientific rigor while fostering innovation that ultimately benefits patient care.

Technology in Practice: Platforms and Workflows for Biomarker Quantification

Targeted proteomics represents a cornerstone of modern precision oncology, providing the quantitative accuracy and reproducibility essential for analytical validation of cancer biomarker assays. Unlike discovery-oriented "shotgun" approaches, targeted proteomics employs mass spectrometry to precisely monitor a pre-defined set of peptides, enabling highly sensitive and specific quantification of protein biomarkers. This focused strategy is indispensable for verifying biomarker candidates in complex biological matrices, a critical step in translating potential markers from research into clinical applications. The workflow's robustness hinges on a meticulously optimized sequence of steps—from sample digestion to liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) analysis—each requiring stringent control to ensure data quality and reproducibility for drug development and clinical research [28].

This guide objectively compares the core methodologies and technological alternatives within the targeted proteomics workflow, framing them within the context of analytical validation for cancer biomarkers. We present supporting experimental data and detailed protocols to help researchers and scientists select the optimal strategies for their specific biomarker validation challenges.

Core Workflow of Targeted Proteomics

The foundational workflow of targeted proteomics is designed to transform complex protein samples into analytically tractable peptide measurements with high precision. The following diagram illustrates the logical sequence and key decision points in this multi-stage process.

Sample Preparation and Protein Digestion

The initial phase of sample preparation is critical, as it directly impacts the quality and reproducibility of all downstream data. Efficient sample preparation begins with protein extraction and solubilization from biological materials (e.g., cell cultures, tissue biopsies, or biofluids) using denaturing buffers, often containing urea or RIPA buffer, to ensure full protein accessibility [28]. For formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues—a common clinical resource—novel AFA (Adaptive Focused Acoustics) technology has been shown to improve protein extraction efficiency and reproducibility compared to traditional bead-beating methods, mitigating issues related to variable yield and sample degradation [29].

Following extraction, proteins undergo reduction to cleave disulfide bonds (typically using dithiothreitol - DTT) and alkylation (e.g., with iodoacetamide) to prevent reformation, linearizing the proteins for enzymatic cleavage [28]. The core of sample preparation is protein digestion, most commonly using the serine protease trypsin, which cleaves peptide bonds C-terminal to lysine and arginine residues. This specificity yields peptides with predictable masses and charge states, simplifying subsequent LC-MS/MS analysis. Digestion protocols must be optimized to balance completeness (to avoid missed cleavages) with preventing over-digestion artifacts, often using controlled temperature and reaction time [28]. For complex or membrane protein samples, alternative enzymes like Lys-C may be employed to improve digestion efficiency [28].

Liquid Chromatography (LC) Separation

Following digestion, the complex peptide mixture must be separated before mass spectrometry analysis to reduce sample complexity and mitigate ion suppression effects. Liquid Chromatography is the workhorse for this separation, with reversed-phase chromatography being the most prevalent mode. Peptides are separated based on their hydrophobicity as an organic solvent gradient (typically acetonitrile) elutes them from a C18-coated column [28].

The choice of chromatographic scale involves a critical trade-off between sensitivity, throughput, and robustness, directly impacting assay performance in validation settings. The table below compares the performance characteristics of different LC flow rates, based on empirical benchmarking studies [30].

Table 1: Comparison of LC Flow Rates for Proteomic Analysis

| Flow Rate Scale | Typical Flow Rate | Column i.d. | Key Strengths | Ideal Application in Biomarker Validation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nanoflow (nLC) | < 1 µL/min | 75-100 µm | Exceptional sensitivity, low sample consumption | Verification from sample-limited sources (e.g., microdissected tissue) |

| Capillary (capLC) | 1.5-5 µL/min | 150-300 µm | High sensitivity, excellent robustness & throughput | High-throughput candidate verification in large cohorts |

| Microflow (μLC) | 50-200 µL/min | 1-2.1 mm | High throughput & extreme robustness | Robust, reproducible quantification in clinical cohorts |

Recent studies demonstrate that capillary-flow LC (capLC) operating around 1.5 µL/min provides a robust and sensitive alternative, identifying approximately 2,600 proteins in 30-minute gradients and offering an optimal balance for high-throughput clinical samples [30]. Conversely, microflow LC (μLC) systems, running at higher flow rates (e.g., 50-200 µL/min), excel in throughput and robustness, making them suitable for analyzing large patient cohorts where thousands of samples must be processed with minimal downtime [30].

Mass Spectrometry Analysis: SRM and PRM

The mass spectrometry component is where targeted quantification occurs. In a typical LC-MS/MS experiment, peptides eluting from the LC column are ionized via electrospray ionization (ESI) and introduced into the mass spectrometer [28]. The instrument first performs a survey scan (MS1) to measure the mass-to-charge (m/z) ratios of intact peptide ions [28].

For targeted proteomics, two primary data acquisition techniques are employed:

- Selected Reaction Monitoring (SRM): This gold-standard method, often performed on triple quadrupole instruments, specifically monitors predefined precursor ion → fragment ion transitions for each target peptide. It offers exceptional sensitivity, dynamic range, and precision for quantifying a limited set of targets.

- Parallel Reaction Monitoring (PRM): A high-resolution targeted method performed on Orbitrap or time-of-flight (TOF) instruments. PRM acquires all fragment ions of a selected precursor simultaneously, providing high specificity and allowing retrospective data analysis without pre-defining specific transitions [28].

Both SRM and PRM provide superior quantitative accuracy for validating candidate biomarkers compared to discovery-oriented methods, as they focus the instrument's duty cycle on the most relevant ions, resulting in improved sensitivity, lower limits of quantification, and higher reproducibility.

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The successful implementation of a targeted proteomics workflow depends on a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The following table details key components and their functions within the experimental pipeline.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Targeted Proteomics

| Item/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Digestion Enzyme | Trypsin, Lys-C | Site-specific protein cleavage into analyzable peptides [28]. |

| Denaturant | Urea, RIPA Buffer | Unfolds proteins to make cleavage sites accessible [28]. |

| Reducing Agent | Dithiothreitol (DTT), Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP) | Breaks disulfide bonds to linearize proteins [28]. |

| Alkylating Agent | Iodoacetamide (IAA), Chloroacetamide (CAA) | Caps free thiols to prevent reformation of disulfide bonds [28]. |

| LC Column | C18 reversed-phase columns (varying i.d.) | Separates peptides based on hydrophobicity prior to MS injection [30]. |

| Internal Standards | Stable Isotope-Labeled Standard (SIS) Peptides | Enables precise quantification by correcting for variability in sample prep and MS ionization [31]. |

| Solid-Phase Extraction | C18 cartridges or tips | Desalts and concentrates peptide samples post-digestion [28]. |

Among these, stable isotope-labeled standard (SIS) peptides are particularly crucial for analytical validation. These synthetic peptides, identical to target peptides but with a heavy isotope label, are spiked into the sample at a known concentration before digestion. They correct for sample preparation losses and ionization variability, enabling highly accurate and precise quantification—a non-negotiable requirement for biomarker assay validation [31].

Analytical Validation in Cancer Biomarker Research

For a cancer biomarker assay to achieve clinical utility, it must undergo rigorous analytical validation to establish its performance characteristics. This process, guided by frameworks from organizations like the FDA and the NCI's Diagnostics Evaluation Branch (DEB), assesses key metrics including sensitivity, specificity, precision, and reproducibility [15]. The targeted proteomics workflow is uniquely positioned to meet these demands.

Validation begins with defining the assay's intended use and then systematically testing its performance. Key parameters include:

- Sensitivity and Specificity: Determining the lowest concentration of the biomarker that can be reliably detected (Limit of Detection, LOD) and quantified (Limit of Quantification, LOQ) with high specificity against a complex background [32].

- Precision and Reproducibility: Evaluating the assay's coefficient of variation (CV) across repeated measurements within runs (intra-assay) and between different runs, operators, and laboratories (inter-assay) [32].

- Linearity and Dynamic Range: Establishing that the quantitative response is linear across the expected physiological range of the biomarker [30].

The NCI's DEB supports this process through initiatives like the UH2/UH3 cooperative agreements, which fund projects focused on the analytical and clinical validation of biomarkers and assays for use in NCI-supported cancer trials [15]. This underscores the critical role of standardized, validated assays in translating proteomic discoveries into tools that can guide treatment decisions, such as companion diagnostics that link specific protein biomarkers to FDA-approved targeted therapies [32].

Mass spectrometry-based targeted proteomics, with its robust workflows from digestion to LC-MS/MS analysis, provides an indispensable platform for the analytical validation of cancer biomarker assays. The strategic selection of methodologies—from sample preparation techniques to the choice between LC flow rates and MS acquisition modes—directly impacts the sensitivity, throughput, and ultimate success of biomarker verification.

As the field advances, the integration of more robust capillary-flow LC systems, highly specific PRM acquisitions, and the mandatory use of stable isotope standards is setting a new standard for precision and reproducibility. By adhering to these rigorously validated workflows, researchers and drug development professionals can confidently generate the high-quality data necessary to bridge the gap between promising biomarker candidates and clinically actionable diagnostic tools, ultimately advancing the goals of precision oncology.

The analytical validation of cancer biomarker assays represents a critical frontier in molecular pathology and diagnostic research. For researchers and drug development professionals, selecting the appropriate immunoassay platform is not merely a technical choice but a fundamental decision that directly impacts data reliability, clinical translation, and therapeutic development. Immunoassay technologies have evolved substantially from their origins in radioimmunoassay to encompass a diverse toolkit for protein detection and quantification [33]. Within cancer biomarker research, the validation of assays requires careful consideration of multiple performance parameters including sensitivity, specificity, reproducibility, and analytical context.

This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of three major immunoassay platforms—ELISA, Immunohistochemistry (IHC), and emerging techniques—focusing on their technical principles, experimental methodologies, performance characteristics, and applications in cancer biomarker validation. Understanding the comparative strengths and limitations of each platform enables researchers to make informed decisions that align with their specific experimental requirements, whether for biomarker discovery, clinical validation, or therapeutic monitoring.

Technical Principles and Methodologies

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

ELISA operates on the principle of detecting antigen-antibody interactions through enzyme-linked conjugates and chromogenic substrates that generate measurable color changes [34]. The core components include a solid-phase matrix (typically 96-well microplates), enzyme-labeled antibodies (conjugates), specific substrates, and wash buffers to remove unbound components [34]. The most common enzymes used for labeling are horseradish peroxidase (HRP) and alkaline phosphatase (AP), which react with substrates like tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) to produce quantifiable color signals measured spectrophotometrically at 450nm [34].

Several ELISA formats have been developed for different applications:

- Direct ELISA: Uses a single enzyme-linked antibody directly binding the antigen, offering simplicity but potentially lower sensitivity [33].

- Indirect ELISA: Employs an unlabeled primary antibody followed by an enzyme-linked secondary antibody, enhancing sensitivity through signal amplification [34].

- Sandwich ELISA: Requires two antibodies binding to different epitopes of the target antigen, offering high specificity and sensitivity, though it requires larger antigens with multiple epitopes [33].

- Competitive ELISA: Based on competition between sample antigens and labeled analogs for limited antibody binding sites, making it ideal for detecting small molecules or low-abundance targets [33].

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

IHC combines immunological, histological, and biochemical principles to detect specific antigens within tissue sections while preserving morphological context [35]. The technique relies on monoclonal or polyclonal antibodies tagged with labels such as fluorescent compounds or enzymes that selectively bind to target antigens in biological tissues [35]. IHC can be performed through direct methods (labeled primary antibodies) or indirect methods (unlabeled primary antibodies with labeled secondary antibodies), with the latter providing enhanced sensitivity through signal amplification [35].

The critical distinction of IHC lies in its ability to provide spatial information about protein expression and distribution within the tissue architecture, allowing researchers to correlate biomarker expression with specific cell types, subcellular localization, and pathological features [36]. This spatial context is particularly valuable in cancer research for understanding tumor heterogeneity, tumor-microenvironment interactions, and compartment-specific biomarker expression.

Emerging and Hybrid Techniques

Innovative approaches are continually expanding the immunoassay toolbox:

- Histo-ELISA: This hybrid technique combines elements of conventional ELISA and standard ABC immunostaining to enable both quantification of target proteins and observation of related morphological changes concurrently [37]. It substitutes DAB with TMB peroxidase substrate and uses ELISA reader evaluation while maintaining tissue structure visualization.

- Digital ELISA: Emerging digital ELISA platforms offer significantly enhanced sensitivity, achieving up to 50-fold improvement over conventional ELISA through single-molecule detection methods [33].

- Bead-Based Immunoassays: These utilize antibody-coated beads distinguished by color, fluorescence, or size, enabling robust multiplexing capabilities for detecting multiple analytes within a single sample while maintaining high sensitivity and dynamic range [33].

- Novel Applications: Research continues to develop specialized assays such as simultaneous detection of p16 and Ki-67 biomarkers for cervical cancer screening, demonstrating the adaptability of ELISA platforms to specific clinical needs [38].

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

Direct Performance Comparison

Table 1: Direct Comparison of Immunoassay Platforms for Cancer Biomarker Analysis

| Parameter | ELISA | IHC | Bead-Based Assays | Histo-ELISA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantification Capability | Fully quantitative [33] | Semi-quantitative at best [37] | Fully quantitative [33] | Fully quantitative with spatial context [37] |

| Sensitivity | High (picogram range) [36] | Medium [36] | High to ultra-high [33] | High, comparable to ELISA [37] |

| Multiplexing Capacity | Singleplex (typically) [33] | Limited multiplexing (up to 4 targets with fluorescence) [36] | High multiplexing (dozens of targets) [33] | Singleplex [37] |

| Spatial Context | No tissue morphology [37] | Preserves tissue morphology and spatial distribution [35] [36] | No tissue morphology | Preserves tissue morphology [37] |

| Throughput | High [36] | Low to medium | High [33] | Medium [37] |

| Reproducibility | Medium to high [33] | Medium (subject to interpretation variability) [35] | High [33] | High (low coefficient of variation) [37] |

| Dynamic Range | Medium (2-3 orders of magnitude) [33] | Limited | High (3-5 orders of magnitude) [33] | Comparable to ELISA [37] |

| Sample Requirements | Cell lysates, biological fluids (serum, plasma) [34] [36] | Tissue sections [35] | Small sample volumes (25-150μL) [33] | Tissue sections [37] |

Experimental Correlation Studies

Direct comparative studies between ELISA and IHC demonstrate complex relationships between these platforms. A 1999 study comparing ELISA and IHC for components of the plasminogen activation system in cancer lesions revealed Spearman correlation coefficients ranging from 0.41 to 0.78 across different biomarkers [39]. While higher IHC score categories consistently associated with increased median ELISA values, significant overlap of ELISA values between different IHC scoring classes indicated that these techniques are not directly interchangeable [39].

The correlation performance varied by cancer type, with stronger correlations observed in breast carcinoma lesions compared to melanoma lesions, highlighting the influence of tissue and biomarker characteristics on platform agreement [39]. This underscores the importance of context-specific validation when comparing data across different immunoassay platforms.

Application-Specific Performance

Table 2: Platform Selection Guide for Specific Research Applications

| Research Application | Recommended Platform | Key Advantages | Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biomarker Quantification in Biofluids | ELISA or Bead-Based Assays | High sensitivity, fully quantitative, high throughput | Detects and quantifies peptides, proteins, and hormones in biological fluids [34] [33] |

| Tumor Tissue Biomarker Localization | IHC | Spatial context, cell-specific information, correlation with histopathology | Visualizes marker distribution in tissues and tumor heterogeneity [35] [40] |

| Multiplex Biomarker Panels | Bead-Based Immunoassays | Simultaneous quantification of multiple analytes, conserved sample volume | Quantifies multiple protein biomarkers in one run [33] |

| Quantitative Tissue Biomarker Analysis | Histo-ELISA | Combines quantification with morphological preservation | Quantifies target proteins while observing morphological changes [37] |