Next-Generation Sequencing in Cancer Genomics: Comprehensive Protocols from Foundational Principles to Clinical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive examination of next-generation sequencing (NGS) protocols and their transformative impact on cancer genomics.

Next-Generation Sequencing in Cancer Genomics: Comprehensive Protocols from Foundational Principles to Clinical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive examination of next-generation sequencing (NGS) protocols and their transformative impact on cancer genomics. Covering foundational principles, methodological approaches, troubleshooting strategies, and validation frameworks, we detail how NGS enables comprehensive genomic profiling for precision oncology. The content explores diverse sequencing platforms, library preparation techniques, and analytical pipelines for detecting somatic mutations, structural variants, and biomarkers relevant to therapeutic decision-making. Special emphasis is placed on practical implementation challenges, including sample quality considerations, bioinformatics requirements, and clinical validation pathways. With insights into emerging trends like liquid biopsies and single-cell sequencing, this resource serves as an essential guide for researchers and drug development professionals advancing molecularly-driven cancer care.

Foundations of NGS in Cancer Genomics: From Historical Context to Core Principles

The evolution of DNA sequencing technologies from the Sanger method to massively parallel sequencing (Next-Generation Sequencing, NGS) represents a transformative shift in biomedical research, particularly in cancer genomics. This technological revolution has enabled researchers to move from analyzing single genes to comprehensively characterizing entire cancer genomes, transcriptomes, and epigenomes with unprecedented speed and resolution. Sanger sequencing, developed in 1977, established the foundational principles of sequencing technology and remains the gold standard for accuracy in validating specific genetic variants [1]. However, the emergence of NGS platforms has addressed the critical limitations of throughput and scalability, making large-scale projects like The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) feasible and revolutionizing our understanding of cancer biology [2] [3].

In clinical oncology, NGS has become indispensable for identifying somatic mutations, fusion genes, copy number alterations, and other molecular features that drive tumorigenesis. These insights facilitate molecular tumor subtyping, prognostication, and selection of targeted therapies. The ability to detect rare cancer-associated variants in complex tumor samples has positioned NGS as a cornerstone of precision oncology, enabling therapeutic decisions based on the unique genetic profile of individual tumors [4]. This article provides a comprehensive technical overview of sequencing technologies, their applications in cancer research, and detailed protocols for implementing these methods in genomic studies.

Technological Principles and Comparison

Sanger Sequencing: The Foundational Method

Sanger sequencing operates on the principle of chain termination using dideoxynucleotide triphosphates (ddNTPs). These modified nucleotides lack the 3'-hydroxyl group necessary for phosphodiester bond formation, causing DNA polymerase to terminate synthesis when incorporated into a growing DNA strand. The process involves four main steps: (1) DNA template preparation, (2) chain termination PCR with fluorescently-labeled ddNTPs, (3) fragment separation by capillary electrophoresis, and (4) detection via laser-induced fluorescence to generate a chromatogram [1].

The key advantage of Sanger sequencing is its exceptional accuracy and long read lengths (up to 1000 bp), making it ideal for confirming mutations identified through NGS and for sequencing small genomic regions. However, its low throughput and limited sensitivity for detecting variants in heterogeneous samples (typically >20% allele frequency) restrict its utility in comprehensive cancer genomic profiling [1].

Massively Parallel Sequencing: High-Throughput Paradigm

NGS technologies employ a fundamentally different approach characterized by parallel sequencing of millions of DNA fragments. While platform-specific implementations vary, all NGS methods share common principles: (1) library preparation through DNA fragmentation and adapter ligation, (2) clonal amplification of fragments (except for single-molecule platforms), (3) cyclic sequencing through synthesis or ligation, and (4) imaging-based detection [5]. This massively parallel approach enables sequencing of entire human genomes in days at a fraction of the cost of Sanger sequencing, with sufficient depth to detect low-frequency somatic mutations in tumor samples.

Comparative Analysis of Sequencing Platforms

Table 1: Technical comparison of sequencing platforms and their applications in cancer genomics

| Characteristic | Sanger Sequencing | Next-Generation Sequencing |

|---|---|---|

| Principle | Chain termination with ddNTPs [1] | Massively parallel sequencing [5] |

| Throughput | Low (single fragment per reaction) [1] | High (millions of fragments simultaneously) [5] |

| Read Length | Long (600-1000 bp) [1] | Short to long (50-300 bp for Illumina; >10 kb for PacBio) |

| Cost per Mb | High for large volumes [1] | Significantly lower [1] |

| Variant Sensitivity | ~20% allele frequency [1] | 1-5% allele frequency with sufficient depth |

| Primary Cancer Applications | Mutation validation, targeted gene sequencing [1] | Whole genome/exome sequencing, transcriptomics, fusion detection, biomarker discovery [5] [4] |

Table 2: NGS enrichment methods for targeted sequencing in cancer research

| Enrichment Method | Principle | Advantages | Limitations | Cancer Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hybridization-Based Capture | Solution-based hybridization with biotinylated probes to target regions [5] | High uniformity, flexible target design, cost-effective for large regions | Requires more input DNA, longer protocol | Comprehensive cancer panels, whole exome sequencing [4] |

| Amplicon-Based (e.g., Microdroplet PCR) | PCR amplification of target regions within water-in-oil emulsions [5] | Fast protocol, low DNA input, robust performance | Limited multiplexing capability, lower uniformity | Targeted mutation profiling, circulating tumor DNA analysis |

Applications in Cancer Genomics

Mutation Detection in Heterogeneous Disorders

NGS has proven particularly valuable for diagnosing genetically heterogeneous cancers where multiple genes can contribute to similar phenotypes. In congenital muscular dystrophy research, which presents diagnostic challenges due to phenotypic variability, targeted NGS panels covering 321 exons across 12 genes demonstrated superior diagnostic yield compared to sequential Sanger sequencing. Both hybridization-based and microdroplet PCR enrichment methods showed excellent sensitivity and specificity for mutation detection, though Sanger sequencing fill-in was still required for regions with high GC content or repetitive sequences [5].

Fusion Gene Detection in Solid Tumors

The detection of oncogenic fusion genes, such as NTRK fusions, exemplifies the clinical importance of NGS in cancer diagnosis and treatment selection. RNA-based hybrid-capture NGS has demonstrated high sensitivity for identifying both known and novel NTRK fusions across diverse tumor types, with a prevalence of 0.35% in a real-world cohort of 19,591 solid tumors. Tumor types with the highest NTRK fusion prevalence included glioblastoma (1.91%), small intestine tumors (1.32%), and head and neck tumors (0.95%) [4]. The comprehensive nature of NGS-based fusion detection directly impacts therapeutic decisions, as NTRK fusions are clinically actionable biomarkers with FDA-approved targeted therapies (larotrectinib, entrectinib, repotrectinib) showing high response rates [4].

NGS Fusion Detection Workflow

Biomarker Discovery and Validation

NGS enables the discovery of novel cancer biomarkers through integrated analysis of multiple molecular datasets. In hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), comprehensive profiling of cleavage and polyadenylation specificity factors (CPSFs) using NGS data from TCGA revealed that CPSF1, CPSF3, CPSF4, and CPSF6 show significant transcriptional upregulation in tumors, with overexpression correlated with advanced disease progression and poor prognosis [3]. Functional validation using reverse transcription-quantitative PCR and cell proliferation assays confirmed the oncogenic roles of CPSF3 and CPSF7, demonstrating how NGS-driven discovery can identify novel therapeutic targets [3].

Similarly, in glioblastoma, integrated CRISPR/Cas9 screens with NGS analysis identified RBBP6 as an essential regulator of glioblastoma stem cells through CPSF3-dependent alternative polyadenylation, revealing a novel therapeutic vulnerability [6]. These examples illustrate how NGS facilitates the transition from biomarker discovery to functional validation and therapeutic development.

Experimental Protocols

DNA Hybrid-Capture Targeted Sequencing for Mutation Detection

Application Note: This protocol is adapted from methods used for congenital muscular dystrophy gene panel sequencing [5] and comprehensive genomic profiling for fusion detection [4], optimized for detecting somatic mutations in cancer samples.

Materials and Reagents:

- Input DNA: 50-200ng from FFPE tissue or fresh frozen tumor samples

- Hybridization capture reagents: Biotinylated oligonucleotide probes targeting cancer-related genes

- Library preparation kit: Fragmentation enzymes, end repair, A-tailing, and ligation reagents

- Sequencing platform: Illumina, Ion Torrent, or similar NGS systems

- Bioinformatics tools: BWA-MEM for alignment, GATK for variant calling, VarScan for somatic mutation detection

Procedure:

- DNA Shearing and Quality Control: Fragment genomic DNA to 150-300bp using acoustic shearing or enzymatic fragmentation. Assess DNA quality and quantity using fluorometric methods.

- Library Preparation: Perform end repair, 3' adenylation, and adapter ligation using dual-indexed adapters to enable sample multiplexing.

- Hybrid Capture: Denature library DNA and hybridize with biotinylated probes for 16-24 hours. Capture probe-bound fragments using streptavidin-coated magnetic beads.

- Post-Capture Amplification: Perform 10-12 cycles of PCR to amplify captured libraries.

- Sequencing: Pool libraries at equimolar concentrations and sequence on appropriate NGS platform (minimum 150bp paired-end reads, 500x coverage for tumor samples).

- Data Analysis: Align sequences to reference genome, perform quality control metrics, and call variants using validated bioinformatics pipelines.

Quality Control Considerations:

- Minimum sequencing depth: 500x for tumor samples

- Minimum unique molecular coverage: 100x

- Include positive and negative control samples in each run

- Verify detection sensitivity for variants at 5% allele frequency

RNA Sequencing for Fusion Gene Detection

Application Note: This protocol describes RNA-based hybrid-capture sequencing for detecting oncogenic fusions, adapted from the methodology used for NTRK fusion detection [4].

Materials and Reagents:

- Input RNA: 50-100ng total RNA from FFPE tissue (DV200 > 30%)

- RNA library preparation kit: Including rRNA depletion or poly-A selection reagents

- Hybridization capture reagents: Biotinylated probes targeting fusion partners

- TruSight Oncology 500 or similar comprehensive assay

- Bioinformatics tools: STAR for alignment, Arriba, STAR-Fusion, or Manta for fusion detection

Procedure:

- RNA Extraction and QC: Extract total RNA from tumor tissue. Assess RNA integrity using fragment analyzer or similar system.

- rRNA Depletion: Remove ribosomal RNA using sequence-specific probes.

- Library Preparation: Fragment RNA, synthesize cDNA, and add dual-indexed adapters.

- Hybrid Capture: Hybridize with bait set covering known and potential fusion partners (e.g., full coding regions of NTRK1/2/3).

- Sequencing: Sequence libraries with minimum 100M reads per sample (2x100bp).

- Fusion Calling: Identify fusion transcripts using multiple algorithms with manual review of supporting reads.

Validation:

- Confirm novel fusions by orthogonal methods (RT-PCR, FISH)

- Compare with IHC for protein expression when antibodies available

- Assess functional impact of fusions through pathway analysis

Cancer NGS Analysis Pipeline

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential research reagents and computational tools for cancer NGS studies

| Category | Specific Product/Platform | Application in Cancer NGS | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Library Prep Kits | Illumina TruSight Oncology 500 [4] | Comprehensive genomic profiling | Detects SNVs, indels, fusions, TMB, MSI from FFPE |

| Target Enrichment | Hybrid-capture baits (NimbleGen, IDT) [5] | Targeted sequencing | Customizable content, high uniformity |

| Bioinformatics Tools | cBioPortal [3] | Genomic alteration analysis | Interactive exploration of cancer genomics data |

| Bioinformatics Tools | GSCALite [3] | Cancer pathway analysis | Functional analysis of genes in cancer signaling |

| Expression Databases | UALCAN [3] | Gene expression analysis | CPTAC and TCGA data analysis portal |

| Survival Analysis | Kaplan-Meier Plotter [3] | Prognostic biomarker validation | Correlation of gene expression with patient survival |

| Immune Infiltration | TIMER [3] | Tumor immunology | Immune cell infiltration estimation |

| Validation Tools | Sanger Sequencing [1] | NGS variant confirmation | High accuracy for individual variants |

The evolution from Sanger to massively parallel sequencing has fundamentally transformed cancer research and clinical oncology. NGS technologies now enable comprehensive molecular profiling of tumors, revealing the complex genetic alterations that drive cancer progression and treatment resistance. The applications described—from detecting mutations in heterogeneous tumors to identifying actionable gene fusions and novel biomarkers—demonstrate the indispensable role of NGS in advancing precision oncology.

As sequencing technologies continue to evolve, with reductions in cost and improvements in accuracy and throughput, their integration into routine clinical practice will expand. Future developments in single-cell sequencing, long-read technologies, and multi-omics integration will further enhance our ability to decipher cancer complexity, ultimately leading to more effective personalized cancer therapies and improved patient outcomes.

Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) has fundamentally transformed oncology research and clinical practice by enabling comprehensive genomic profiling of tumors at unprecedented resolution and scale [7]. This technology allows researchers to simultaneously sequence millions of DNA fragments, providing unparalleled insights into genetic variations, gene expression patterns, and epigenetic modifications that drive carcinogenesis [8]. In contrast to traditional Sanger sequencing, which processes single DNA fragments sequentially, NGS employs massively parallel sequencing architecture, making it possible to interrogate hundreds to thousands of genes in a single assay [7]. This capability is particularly valuable for deciphering the complex genomic landscape of cancer, a disease characterized by diverse and interacting molecular alterations spanning single nucleotide variations, copy number alterations, chromosomal rearrangements, and gene fusions [9].

The implementation of NGS in cancer research has accelerated the development of precision oncology approaches, where treatments are increasingly tailored to the specific molecular profile of a patient's tumor [7]. The core NGS workflow encompasses multiple interconnected stages, each with critical technical considerations that collectively determine the success and reliability of genomic analyses. This application note provides a detailed examination of these workflow components, with specific emphasis on protocols and methodological considerations essential for cancer genomics research.

Core NGS Workflow: From Sample to Insight

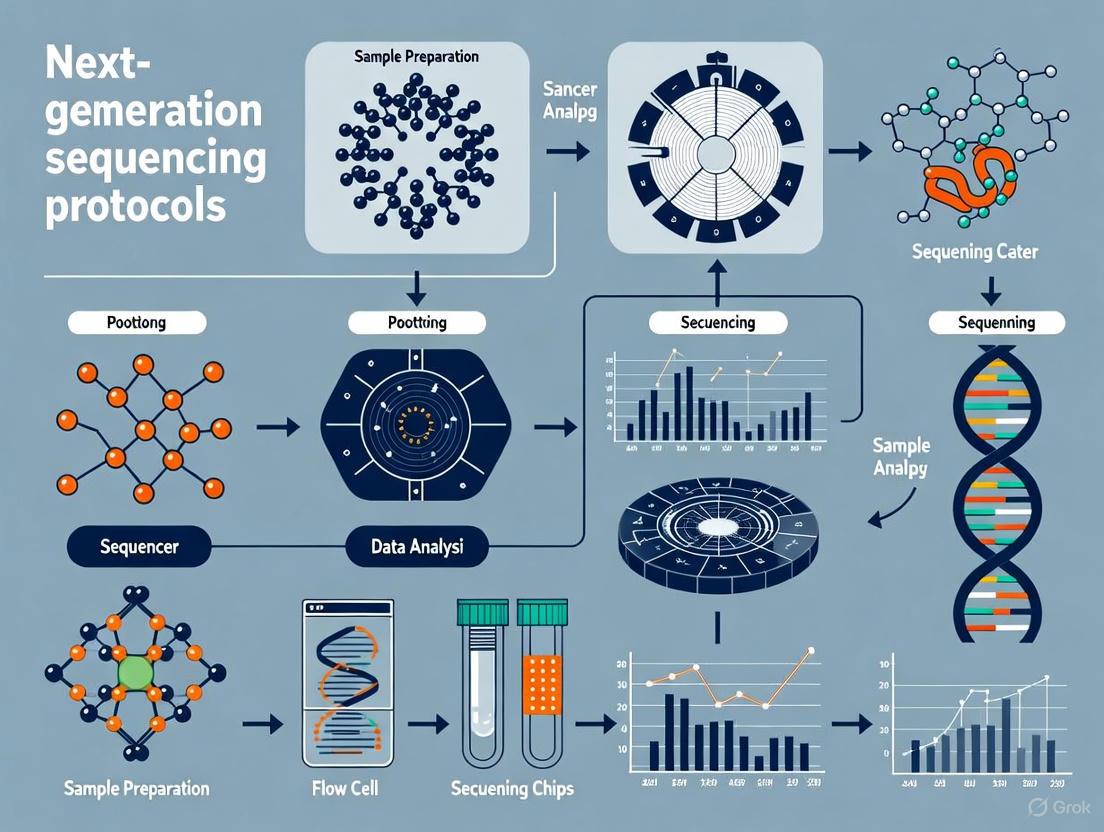

The following diagram illustrates the complete NGS workflow, from sample preparation through final data analysis, highlighting key decision points and processes specific to cancer genomics research.

Sample Preparation: Critical First Steps

Nucleic Acid Extraction and Quality Control

The initial and perhaps most critical phase of the NGS workflow begins with the extraction of high-quality nucleic acids from biological samples [10]. In cancer genomics, sample types range from fresh frozen tissues and cell lines to more challenging specimens like Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded (FFPE) tissue blocks and liquid biopsies [11]. The quality of extracted nucleic acids profoundly influences all subsequent steps, making rigorous quality control (QC) essential.

Protocol: DNA Extraction from FFPE Tissue Sections [11] [12]

- Sample Preparation: Cut 2-5 sections of 5-10µm thickness from FFPE blocks containing at least 20% tumor tissue (verified by pathological review).

- Deparaffinization: Incubate sections with xylene or a commercial deparaffinization solution, followed by ethanol washes.

- Proteinase K Digestion: Digest tissue overnight at 56°C with proteinase K in appropriate buffer to reverse formalin cross-links.

- Nucleic Acid Purification: Use silica-column or magnetic bead-based purification systems specifically validated for FFPE samples.

- DNase Treatment: For RNA extraction, include DNase digestion to remove genomic DNA contamination.

- Quantification and QC:

- Quantify DNA using fluorometric methods (Qubit dsDNA HS Assay) rather than spectrophotometry [12].

- Assess DNA integrity via Fragment Analyzer, TapeStation, or Bioanalyzer. For FFPE-derived DNA, a DV200 value >50-70% is generally acceptable [11].

- Verify purity using A260/A280 and A260/A230 ratios (ideal values: 1.8-2.0).

Sample Quality Requirements for NGS [12]

| Sample Type | Minimum Quantity | Quality Metrics | Storage/Shipment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomic DNA (Blood/Tissue) | 100 ng (WGS)50 ng (Targeted) | A260/A280: 1.8-2.0A260/A230: 2.0-2.2DNA Integrity Number (DIN) >7 | -20°C or belowDry ice shipment |

| FFPE DNA | 50-100 ng | DV200 >50%Fragment size: 200-1000 bp | Room temperatureProtect from moisture |

| Total RNA | 100 ng (Standard RNA-seq)1 ng (Ultra-low Input) | RIN >7DV200 >70% for FFPE | -80°CRNase-free conditions |

| Cell-Free DNA | 1-50 ng (depending on panel) | Fragment size: ~160-180 bp | -80°CAvoid freeze-thaw cycles |

Library Preparation: Converting Nucleic Acids to Sequencable Formats

Library preparation transforms extracted nucleic acids into formats compatible with NGS platforms through fragmentation, adapter ligation, and optional indexing steps [10]. The choice of library preparation method depends on the experimental goals, sample type, and available resources.

Protocol: Library Preparation Using Hybridization Capture [11]

DNA Fragmentation:

- Fragment 10-1000 ng genomic DNA to 150-300 bp fragments using acoustic shearing (Covaris) or enzymatic fragmentation (tn5 transposase).

- For FFPE-derived DNA, additional fragmentation may be unnecessary due to inherent degradation.

End Repair and A-Tailing:

- Convert fragmented DNA to blunt ends using end repair enzyme mix (30 minutes at 20-25°C).

- Add adenine nucleotide to 3' ends using A-tailing enzyme (30 minutes at 37°C).

Adapter Ligation:

- Ligate platform-specific adapters containing sequencing motifs and dual-index barcodes to enable sample multiplexing (15-60 minutes at 20-25°C).

- Clean up ligation reactions using magnetic beads to remove excess adapters.

Library Amplification:

Target Enrichment:

- Hybridize amplified libraries with biotinylated oligonucleotide probes targeting specific genomic regions (16-24 hours at 65°C).

- Capture probe-bound fragments using streptavidin-coated magnetic beads.

- Wash to remove non-specific binding and perform post-capture amplification (4-10 PCR cycles).

Final Library QC:

- Quantify using fluorometric methods (Qubit).

- Assess size distribution using Fragment Analyzer, TapeStation, or Bioanalyzer.

- Validate library molarity via qPCR using library quantification kits.

Comparison of Target Enrichment Methods [11]

| Parameter | Amplicon-Based | Hybridization Capture |

|---|---|---|

| Input DNA | 1-100 ng | 10-1000 ng |

| Workflow Duration | 6-8 hours | 2-3 days |

| On-Target Rate | >90% | 50-80% |

| Uniformity | Lower (amplicon-specific bias) | Higher (Fold-80 penalty: 1.5-3) |

| Target Region Flexibility | Limited to predefined amplicons | Flexible; suitable for large targets |

| Ability to Detect CNVs | Limited | Good |

| Cost | Lower | Higher |

| Optimal Use Cases | Hotspot mutation screening, small panels | Whole exome sequencing, large panels |

Sequencing Platforms and Data Generation

The selection of an appropriate sequencing platform represents a critical decision point in experimental design, with significant implications for data quality, throughput, and analytical approaches [7].

Comparative Analysis of NGS Platforms [14] [7]

| Platform | Technology | Read Length | Throughput per Run | Error Profile | Optimal Cancer Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina NovaSeq | Fluorescent reversible terminators | 50-300 bp (paired-end) | 8000 Gb | Substitution errors (0.1-0.5%) | Whole genome sequencing, large cohort studies |

| Illumina MiSeq | Fluorescent reversible terminators | 25-300 bp (paired-end) | 15 Gb | Substitution errors (0.1-0.5%) | Targeted panels, validation studies |

| Ion Torrent PGM | Semiconductor sequencing | 200-400 bp | 2 Gb | Homopolymer errors | Rapid mutation profiling, small panels |

| PacBio Revio | Single Molecule Real-Time (SMRT) | 10-50 kb | 360 Gb | Random errors (~5-15%) | Structural variant detection, fusion genes |

| Oxford Nanopore | Nanopore sensing | Up to 4 Mb | 100-200 Gb | Random errors (~5-20%) | Real-time sequencing, isoform detection |

Data Analysis: From Raw Sequences to Biological Insights

The transformation of raw sequencing data into biologically meaningful information requires a multi-stage analytical approach with specialized computational tools at each step [8].

Quality Control Metrics for Targeted Sequencing

Rigorous quality assessment at multiple stages of the analytical pipeline is essential for generating reliable, interpretable results [13].

Key NGS Quality Metrics and Interpretation [13]

| Metric | Definition | Optimal Range | Clinical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Depth of Coverage | Number of times a base is sequenced | >100X for somatic variants>500X for liquid biopsies | Ensures detection sensitivity for low-frequency variants |

| On-Target Rate | Percentage of reads mapping to target regions | 50-80% (hybridization capture)>90% (amplicon) | Measures enrichment efficiency; impacts cost and sensitivity |

| Uniformity | Evenness of coverage across targets (Fold-80 penalty) | 1.5-3.0 | Affects ability to detect variants in poorly covered regions |

| Duplicate Rate | Percentage of PCR/optical duplicates | <10-20% (depending on application) | High rates indicate limited library complexity or over-amplification |

| GC Bias | Deviation from expected GC distribution | <10% deviation | Impacts detection in GC-rich or AT-rich regions |

Protocol: Somatic Variant Calling from Tumor-Normal Pairs

Data Preprocessing:

- Quality control: Run FastQC on raw FASTQ files to assess per-base quality scores, GC content, and adapter contamination.

- Adapter trimming: Use Trimmomatic or Cutadapt to remove adapter sequences and low-quality bases.

Alignment to Reference Genome:

- Align trimmed reads to reference genome (GRCh38) using BWA-MEM or STAR (for RNA-seq).

- Convert SAM to BAM format, sort by coordinate, and mark duplicates using Picard Tools.

Variant Calling:

- For DNA sequencing: Use MuTect2 (GATK) for SNVs/indels, Control-FREEC for CNVs, and Manta for structural variants.

- For RNA sequencing: Use STAR-Fusion for gene fusions and RSEM for expression quantification.

Variant Annotation and Prioritization:

- Annotate variants using ANNOVAR or VEP with databases including COSMIC, ClinVar, gnomAD, and dbNSFP.

- Filter variants based on population frequency (<1% in control populations), functional impact (missense, nonsense, splice-site), and clinical relevance (OncoKB, CIViC).

Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful implementation of NGS workflows requires carefully selected reagents and materials optimized for each procedural step.

Essential Research Reagents for NGS in Cancer Genomics

| Reagent Category | Specific Products | Function | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction | QIAamp DNA FFPE Kit, AllPrep DNA/RNA Kit, Qubit dsDNA HS Assay | Isolation and quantification of nucleic acids from various sample types | FFPE-specific kits address cross-linking; fluorometric quantification preferred over spectrophotometry [11] [12] |

| Library Preparation | KAPA HyperPlus Kit, Illumina Nextera Flex, IDT xGen cfDNA Library Prep | Fragmentation, adapter ligation, and amplification for sequencing | PCR cycles should be minimized to reduce duplicates and bias; molecular barcodes enable duplicate removal [11] [13] |

| Target Enrichment | Illumina AmpliSeq Cancer Hotspot Panel, IDT xGen Pan-Cancer Panel, Roche NimbleGen SeqCap EZ | Selection of genomic regions of interest | Amplicon-based: rapid, low input; Hybridization capture: better uniformity, larger targets [11] |

| Sequencing Reagents | Illumina SBS Chemistry, Ion Torrent Semiconductor Sequencing Kits, PacBio SMRTbell | Nucleotide incorporation and signal detection during sequencing | Platform-specific; determine read length, error profiles, and throughput capabilities [14] [7] |

| Bioinformatics Tools | BWA, GATK, ANNOVAR, Franklin by Genoox, TumorSecTM | Data analysis, variant calling, and interpretation | Automated pipelines (TumorSecTM) standardize analysis; population-specific databases improve accuracy [8] [11] |

The comprehensive NGS workflow outlined in this application note provides a robust framework for implementing next-generation sequencing in cancer genomics research. Each component—from sample preparation through data analysis—requires careful consideration and optimization to generate clinically actionable insights. As NGS technologies continue to evolve, with emerging approaches including single-cell sequencing, spatial transcriptomics, and artificial intelligence-enhanced analysis, the fundamental workflow principles described here will remain essential for generating reliable, reproducible genomic data to advance precision oncology [7]. The integration of standardized protocols, rigorous quality control measures, and appropriate bioinformatics approaches enables researchers to fully leverage the transformative potential of NGS in deciphering the molecular complexity of cancer.

Cancer is fundamentally a genetic disease driven by the accumulation of molecular alterations that disrupt normal cellular functions, leading to uncontrolled proliferation and metastasis. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized our ability to detect and characterize these alterations with unprecedented resolution and scale, moving beyond single-gene analyses to comprehensive genomic profiling [9] [15]. The complex genomic landscape of cancer is primarily shaped by four key types of genetic alterations: single nucleotide variants (SNVs), copy number variations (CNVs), gene fusions, and various biomarkers that predict therapy response [16] [17]. These alterations activate oncogenic pathways, inactivate tumor suppressors, and create dependencies that can be therapeutically targeted, forming the foundation of precision oncology.

The clinical utility of comprehensive genomic profiling lies in its ability to identify targetable mutations across diverse cancer types simultaneously, providing a more efficient and tissue-saving approach compared to serial single-gene tests [17]. Large-scale genomic studies of advanced solid tumors have demonstrated that over 90% of patients harbor therapeutically actionable alterations, with approximately 29% possessing biomarkers linked to FDA-approved therapies and another 28% having alterations eligible for off-label targeted treatments [16]. This wealth of genomic information, when interpreted through structured frameworks like the Association for Molecular Pathology (AMP) variant classification system, enables clinicians to match patients with appropriate targeted therapies and immunotherapies based on the molecular characteristics of their tumors rather than solely on histology [18].

Characterization of Major Genetic Alterations

Single Nucleotide Variants (SNVs) and Small Insertions/Deletions (Indels)

Single nucleotide variants (SNVs) represent the most frequent class of somatic mutations in cancer, occurring when a single nucleotide base is substituted for another [16]. Small insertions or deletions (indels), typically involving fewer than 50 base pairs, constitute another common mutation type [17]. These alterations can have profound functional consequences depending on their location and nature. Missense mutations result in amino acid substitutions that may alter protein function, nonsense mutations create premature stop codons leading to truncated proteins, and splice site variants can disrupt normal RNA processing [9]. Frameshift mutations caused by indels that alter the reading frame often produce completely aberrant protein products.

Oncogenic SNVs frequently occur in critical signaling pathways that regulate cell growth, differentiation, and survival. For example, mutations in the KRAS gene are found in approximately 10.7% of solid tumors and drive constitutive activation of the MAPK signaling pathway, promoting uncontrolled cellular proliferation [18]. Similarly, EGFR mutations in lung cancer and BRAF V600E mutations in melanoma and other cancers serve as oncogenic drivers that can be targeted with specific kinase inhibitors [9] [15]. Other clinically significant SNVs include PIK3CA mutations in breast and endometrial cancers, IDH1/2 mutations in gliomas and acute myeloid leukemia, and TP53 mutations across numerous cancer types [17].

The clinical detection of SNVs and indels requires sensitive methods capable of identifying low-frequency variants in heterogeneous tumor samples. NGS technologies can reliably detect variants with variant allele frequencies (VAF) as low as 2-5%, with some optimized assays pushing detection limits below 1% [18] [16]. This sensitivity is crucial for identifying subclonal populations that may drive therapy resistance and for analyzing samples with low tumor purity.

Copy Number Variations (CNVs)

Copy number variations (CNVs) are genomic alterations that result in an abnormal number of copies of a particular DNA segment, ranging from small regions to entire chromosomes [16]. In cancer, CNVs primarily manifest as amplifications of oncogenes or deletions of tumor suppressor genes. Gene amplifications can lead to protein overexpression and constitutive activation of oncogenic signaling pathways, while homozygous deletions often result in complete loss of tumor suppressor function [17].

Therapeutically significant CNVs include HER2 (ERBB2) amplifications in breast and gastric cancers, which predict response to HER2-targeted therapies like trastuzumab and ado-trastuzumab emtansine [19]. MYC amplifications occur in various aggressive malignancies including Burkitt lymphoma and neuroblastoma, while MDM2 amplifications are found in sarcomas and other solid tumors and can be targeted with MDM2 inhibitors [16]. CDKN2A deletions, which remove a critical cell cycle regulator, are common in glioblastoma, pancreatic cancer, and melanoma [17].

CNV detection by NGS relies on measuring sequencing depth relative to a reference genome, with specialized bioinformatics tools like CNVkit used to identify regions with statistically significant deviations from normal copy number [18]. The threshold for defining amplifications varies by laboratory but typically requires an average copy number ≥5, while homozygous deletions are identified by complete absence of coverage in tumor samples despite adequate overall sequencing depth [18].

Gene Fusions and Structural Variants

Gene fusions are hybrid genes created by structural chromosomal rearrangements such as translocations, inversions, or deletions that bring together portions of two separate genes [16]. These events can produce chimeric proteins with novel oncogenic functions or place proto-oncogenes under the control of strong promoter elements, leading to their constitutive expression [9]. NGS technologies, particularly RNA sequencing, have dramatically improved the detection of known and novel gene fusions compared to traditional methods like fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) [17].

Therapeutically targetable fusions include EML4-ALK in non-small cell lung cancer, FGFR2 and FGFR3 fusions in various solid tumors, and NTRK fusions across multiple cancer types, which respond to specific TRK inhibitors [16] [17]. In prostate cancer, gene fusions are particularly common, with TMPRSS2-ERG fusions occurring in approximately 42% of cases [16]. Other clinically significant fusions include ROS1 fusions in lung cancer and RET fusions in thyroid and lung cancers, both of which have approved targeted therapies [17].

Detection methods for gene fusions have evolved significantly with NGS. DNA-based sequencing can identify breakpoints at the genomic level, while RNA sequencing provides direct evidence of expressed fusion transcripts and can detect fusions regardless of the specific genomic breakpoint location [16]. Various computational tools like LUMPY are employed to identify structural variants from sequencing data, with read counts ≥3 typically interpreted as positive results for structure variation detection [18].

Emerging Biomarkers for Therapy Selection

Beyond specific mutations, several genomic biomarkers provide crucial information for therapy selection, particularly for immunotherapy. Tumor Mutational Burden (TMB) measures the total number of mutations per megabase of DNA and serves as a proxy for neoantigen load, with high TMB (TMB-H) predicting improved response to immune checkpoint inhibitors across multiple cancer types [16] [17]. Microsatellite Instability (MSI) results from defective DNA mismatch repair and creates a hypermutated phenotype that is highly responsive to immunotherapy [18]. PD-L1 expression, while often measured by immunohistochemistry, can also be assessed genomically through PD-L1 (CD274) amplifications, which are enriched in metastatic triple-negative breast cancer and associated with immunotherapy response [20].

Additional emerging biomarkers include HRD (Homologous Recombination Deficiency) scores, which predict sensitivity to PARP inhibitors and platinum-based chemotherapy in ovarian, breast, and prostate cancers [17]. Alterations in DNA damage response (DDR) genes including BRCA1, BRCA2, ATM, and ATRX are also associated with treatment response and prognosis [20]. The comprehensive assessment of these biomarkers through NGS panels enables a more complete understanding of tumor immunobiology and therapeutic vulnerabilities.

Table 1: Key Genetic Alterations in Cancer and Their Clinical Applications

| Alteration Type | Key Examples | Primary Detection Methods | Therapeutic Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| SNVs/Indels | KRAS (10.7%), EGFR (2.7%), BRAF (1.7%) [18] | NGS, Sanger sequencing | EGFR inhibitors (e.g., osimertinib), BRAF inhibitors (e.g., vemurafenib) |

| CNVs | HER2 amplification, CDKN2A deletion [17] | NGS, FISH, microarray | HER2-targeted therapies (e.g., trastuzumab), CDK4/6 inhibitors |

| Gene Fusions | EML4-ALK, TMPRSS2-ERG (42% in prostate cancer) [16] | RNA-seq, DNA-seq, FISH | ALK inhibitors (e.g., crizotinib), NTRK inhibitors (e.g., larotrectinib) |

| Immunotherapy Biomarkers | TMB-H, MSI-H, PD-L1 amplification [17] [20] | NGS, immunohistochemistry | Immune checkpoint inhibitors (e.g., pembrolizumab) |

Experimental Protocols for Genetic Alteration Detection

Sample Preparation and Quality Control

Robust sample preparation is foundational to successful NGS-based detection of genetic alterations in cancer. The process begins with formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tumor specimens, which are the most common sample type in clinical oncology, though fresh frozen tissues and liquid biopsy samples are also suitable [18]. Pathological review of hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained slides is essential to assess tumor content, with specimens containing ≥25% tumor nuclei generally recommended for optimal performance [17]. Areas of viable tumor are marked for manual macrodissection or microdissection to enrich tumor content and minimize contamination from normal stromal cells.

Nucleic acid extraction typically utilizes the QIAamp DNA FFPE Tissue Kit (Qiagen) or similar systems designed to handle cross-linked, fragmented DNA from archival specimens [18]. For fusion detection, RNA extraction is performed using systems like the ReliaPrep FFPE gDNA Miniprep System (Promega) [20]. DNA and RNA concentration and quality are assessed using fluorometric methods (Qubit dsDNA HS Assay) and spectrophotometry (NanoDrop), with additional fragment size analysis performed via bioanalyzer systems (Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer) [18] [20]. Minimum quality thresholds typically include DNA quantity ≥20 ng, A260/A280 ratio between 1.7-2.2, and DNA fragment size >250 bp for FFPE samples [18].

For liquid biopsy applications, cell-free DNA (cfDNA) is extracted from plasma samples using specialized kits that efficiently recover short, fragmented DNA. The fraction of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) can be estimated through various methods, with higher fractions generally correlating with improved detection sensitivity for somatic mutations [19].

Library Preparation and Target Enrichment

Library preparation converts extracted nucleic acids into sequencing-compatible formats by fragmenting DNA (if not already fragmented), repairing ends, phosphorylating 5' ends, adding A-tails to 3' ends, and ligating platform-specific adapters [9]. For FFPE-derived DNA, additional steps may be required to repair damage caused by formalin fixation, such as deamination of cytosine bases. Adapter-ligated libraries are then amplified using PCR with primers complementary to the adapter sequences [9].

Target enrichment is crucial for focused cancer panels and can be achieved through either hybrid capture or amplicon-based approaches. Hybrid capture methods using kits such as the Agilent SureSelectXT Target Enrichment System employ biotinylated oligonucleotide baits complementary to targeted genomic regions to pull down sequences of interest from the whole-genome library [18]. This approach provides uniform coverage, handles degraded samples effectively, and enables the inclusion of large genomic regions for assessing TMB and CNVs. Amplicon-based methods use PCR primers designed to flank target regions and are highly efficient for small genomic intervals but may struggle with GC-rich regions and typically require higher DNA input [15].

For comprehensive genomic profiling, integrated DNA and RNA sequencing approaches are increasingly employed. The TruSight Oncology 500 assay (Illumina) simultaneously profiles 523 cancer-related genes from both DNA and RNA in a single workflow, detecting SNVs, indels, CNVs, fusions, and immunotherapy biomarkers like TMB and MSI [17]. Similarly, the OncoExTra assay provides whole exome and whole transcriptome data from tumor-normal pairs, offering exceptionally broad coverage for discovery applications [16].

Sequencing and Data Analysis

Sequencing is typically performed on Illumina platforms (NextSeq 550Dx, NovaSeq X) using sequencing-by-synthesis chemistry, though Ion Torrent, Pacific Biosciences, and Oxford Nanopore technologies are also used in specific contexts [18] [21]. The required sequencing depth varies by application, with targeted panels often sequenced to 500-1000x mean coverage to ensure adequate sensitivity for low-frequency variants, while whole exome sequencing typically achieves 100-200x coverage [18] [16]. For the SNUBH Pan-Cancer v2.0 Panel, an average mean depth of 677.8x is maintained, with at least 80% of targeted bases required to reach 100x coverage for a sample to pass quality thresholds [18].

Bioinformatic analysis begins with base calling and demultiplexing, followed by alignment to the reference genome (GRCh37/hg19 or GRCh38/hg38) using tools like BWA (Burrows-Wheeler Aligner) [20]. Variant calling employs specialized algorithms: Mutect2 is commonly used for SNV and indel detection, CNVkit for copy number analysis, and LUMPY for structural variant identification [18]. For tumor-normal paired samples, additional steps distinguish somatic from germline variants. Variant annotation using tools like SnpEff provides functional predictions and databases like ClinVar and COSMIC help prioritize clinically relevant mutations [18].

Variant filtering and prioritization are critical steps that consider variant allele frequency (with thresholds typically ≥2% for SNVs/indels), functional impact (prioritizing nonsense, splice-site, and missense mutations in cancer genes), and presence in population databases (excluding common polymorphisms) [18]. The final step involves clinical interpretation and classification according to guidelines from the Association for Molecular Pathology (AMP), which categorizes variants into four tiers: Tier I (strong clinical significance), Tier II (potential clinical significance), Tier III (unknown significance), and Tier IV (benign or likely benign) [18].

Table 2: Comparison of NGS Approaches for Detecting Genetic Alterations in Cancer

| Parameter | Targeted Panels | Whole Exome Sequencing | Whole Transcriptome Sequencing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomic Coverage | 50-500 genes | ~20,000 genes (exons) | All expressed genes |

| Primary Applications | Routine clinical testing, therapy selection | Discovery research, novel gene identification | Fusion detection, expression profiling, immune context |

| SNV/Indel Detection | Excellent for targeted regions | Comprehensive across exomes | Limited to expressed variants |

| CNV Detection | Good for known cancer genes | Comprehensive but requires specialized analysis | Indirect via expression levels |

| Fusion Detection | Limited without RNA component | Limited | Excellent for known and novel fusions |

| TMB Assessment | Possible with sufficient gene content | Gold standard | Not applicable |

| Turnaround Time | 1-2 weeks | 2-4 weeks | 2-3 weeks |

| Cost | $$ | $$$ | $$ |

Clinical Applications and Therapeutic Implications

Matching Genetic Alterations to Targeted Therapies

The primary clinical application of comprehensive genomic profiling is to identify targetable genetic alterations that can be matched with specific therapies. Real-world data from tertiary hospitals demonstrates that approximately 13.7% of patients with Tier I variants (strong clinical significance) receive NGS-informed therapy, with response rates varying by cancer type [18]. In one study of 32 patients with measurable lesions who received NGS-based therapy, 12 (37.5%) achieved partial response and 11 (34.4%) achieved stable disease, with a median treatment duration of 6.4 months [18].

Therapeutic matching follows established guidelines such as the AMP tier system and ESCAT (ESMO Scale for Clinical Actionability of Molecular Targets) framework [18]. Level I alterations have validated clinical utility supported by professional guidelines or FDA approval, such as EGFR mutations in NSCLC treated with osimertinib, BRAF V600E mutations treated with vemurafenib/dabrafenib, and NTRK fusions treated with larotrectinib or entrectinib [16] [15]. Level II alterations show promising efficacy in clinical trials or off-label use, such as HER2 amplifications in colorectal cancer treated with HER2-targeted therapies or MET exon 14 skipping mutations treated with MET inhibitors [16].

The therapeutic actionability rate of genomic alterations is remarkably high. Comprehensive genomic profiling of over 10,000 advanced solid tumors revealed that 92.0% of samples harbored therapeutically actionable alterations, with 29.2% containing biomarkers associated with on-label FDA-approved therapies and 28.0% having alterations eligible for off-label targeted treatments [16]. Similarly, a study of 1,000 Indian cancer patients found that 80% had genetic alterations with therapeutic implications, with CGP revealing a greater number of druggable genes (47%) than did small panels (14%) [17].

Biomarkers for Immunotherapy Response

Genomic biomarkers play an increasingly important role in predicting response to immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs). Tumor mutational burden (TMB) has emerged as a quantitative biomarker that measures the total number of mutations per megabase of DNA, with high TMB (TMB-H) generally defined as ≥10 mutations/Mb [17]. TMB-H tumors are thought to generate more neoantigens that make them visible to the immune system, thus increasing the likelihood of response to ICIs [16]. In one cohort, TMB-H was observed in 16% of patients, leading to immunotherapy initiation [17].

Microsatellite instability (MSI) results from defective DNA mismatch repair and creates a hypermutated phenotype that is highly immunogenic [18]. MSI-high (MSI-H) status, detected in approximately 3-5% of all solid tumors, is a pan-cancer biomarker for pembrolizumab approval regardless of tumor origin [16]. MSI status can be determined through multiple methods, including fragment analysis of five mononucleotide repeat markers (BAT-26, BAT-25, D5S346, D17S250, and D2S123) according to the Revised Bethesda Guidelines or through NGS-based approaches that compare microsatellite regions in tumor versus normal DNA [18].

Additional genomic features influencing immunotherapy response include PD-L1 (CD274) amplifications, which are enriched in metastatic triple-negative breast cancer and associated with improved ICI response [20]. Alterations in DNA damage response (DDR) pathways, particularly in homologous recombination repair genes like BRCA1, BRCA2, and ATM, are associated with increased TMB and enhanced immunogenicity [20]. Interestingly, specific mutational signatures such as the APOBEC mutation signature have also been correlated with improved immunotherapy outcomes in certain cancer types [20].

Monitoring Treatment Resistance and Disease Evolution

NGS technologies enable dynamic monitoring of cancer genomes throughout treatment, revealing mechanisms of resistance and disease evolution. Liquid biopsy approaches that sequence circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) from blood samples provide a non-invasive method for monitoring treatment response, detecting minimal residual disease (MRD), and identifying emerging resistance mutations [19]. For example, in EGFR-mutant lung cancer treated with EGFR inhibitors, serial ctDNA analysis can detect the emergence of resistance mutations such as T790M, C797S, and MET amplifications weeks to months before radiographic progression [15].

The fragmentomic analysis of cell-free DNA has emerged as a promising approach to overcome the limitation of low ctDNA concentration in early-stage cancers [19]. This method exploits differences in DNA fragmentation patterns between tumor-derived and normal cell-free DNA, providing an orthogonal approach to mutation-based liquid biopsy. Studies have demonstrated that fragmentomic features can significantly enhance the sensitivity of liquid biopsy for early cancer detection, particularly when combined with mutation analysis [19].

Longitudinal genomic profiling also reveals clonal evolution patterns under therapeutic pressure. Multi-region sequencing of primary and metastatic tumors has demonstrated substantial spatial heterogeneity, while sequential sampling reveals temporal heterogeneity as treatment-resistant subclones expand under selective pressure [17]. Understanding these evolutionary trajectories is crucial for designing combination therapies that prevent or overcome resistance by simultaneously targeting multiple vulnerabilities.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Cancer Genomics Studies

| Reagent/Material | Manufacturer/Provider | Function in Experimental Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| QIAamp DNA FFPE Tissue Kit | Qiagen | Extraction of high-quality DNA from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue specimens |

| ReliaPrep FFPE gDNA Miniprep System | Promega | Extraction of DNA from challenging FFPE samples with improved yield |

| Agilent SureSelectXT Target Enrichment System | Agilent Technologies | Hybrid capture-based enrichment of target genomic regions for sequencing |

| TruSight Oncology 500 Assay | Illumina | Comprehensive genomic profiling of 523 cancer-related genes from DNA and RNA |

| NEBNext Ultra DNA Library Prep Kit | New England Biolabs | Preparation of sequencing libraries with high efficiency and low bias |

| Illumina NextSeq 550Dx System | Illumina | High-throughput sequencing platform for clinical genomic applications |

| Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer | Agilent Technologies | Quality control and fragment size analysis of nucleic acids and libraries |

| Integrated DNA Technologies Pan-Cancer Panel | IDT | Customizable hybrid capture panel targeting 1,021 cancer-related genes |

Visualizing Genetic Alterations and Their Clinical Translation Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the pathway from genetic alteration detection to clinical application, highlighting key decision points in therapeutic matching:

Detection to Therapy Pathway

The NGS experimental workflow encompasses multiple coordinated wet-lab and computational steps as shown below:

NGS Experimental Workflow

Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) has fundamentally transformed the landscape of cancer research and clinical oncology by enabling comprehensive genomic profiling of tumors. This technology facilitates a paradigm shift from traditional histopathology-based classification to molecularly-driven personalized cancer care [7]. By simultaneously interrogating millions of DNA fragments, NGS provides unprecedented insights into the genetic alterations driving tumorigenesis, enabling researchers and clinicians to identify actionable mutations, guide targeted therapy selection, and monitor treatment response [9]. The integration of NGS into oncology research has been accelerated by a deepening understanding of cancer genomics and a growing arsenal of targeted therapeutics, making it an indispensable tool for advancing precision oncology initiatives [22].

NGS technologies have displaced traditional Sanger sequencing due to their massively parallel sequencing architecture, which provides significantly higher throughput, greater sensitivity for detecting low-frequency variants, and the ability to comprehensively detect diverse genomic alterations including single nucleotide variants (SNVs), insertions/deletions (indels), copy number variations (CNVs), gene fusions, and structural variants from a single assay [7]. The continued evolution of NGS platforms and analytical approaches has positioned this technology as the foundation for modern cancer genomics research and clinical applications, from basic discovery to translational research and clinical trials [23].

NGS Methodologies and Technical Approaches

Core NGS Workflow and Platform Selection

The NGS workflow comprises three major components: sample preparation, sequencing, and data analysis [24]. The process begins with extracting genomic DNA from patient samples, followed by library generation that creates random DNA fragments of a specific size range with platform-specific adapters [24]. For targeted approaches, an enrichment step isolates genes or regions of interest through multiplexed PCR-based methods or oligonucleotide hybridization-based methods [24]. The sequenced samples undergo massive parallel sequencing, after which the resulting sequence reads are processed through computational pipelines for base calling, read alignment, variant calling, and variant annotation [24].

Selecting an appropriate NGS method depends on the research objectives, desired genomic information, and available sample types [23]. The major NGS approaches include:

Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS): Provides the most comprehensive analysis of entire genomes, valuable for discovering novel genomic alterations and characterizing novel tumor types [23]. However, WGS requires high sample input, generates complex data, and may not be practical for limited or degraded samples [23].

Exome Sequencing: Focuses on the protein-coding regions of the genome (approximately 1-2%), where most known disease-causing mutations reside [24]. This approach generates data at higher coverage depth than WGS, providing more confidence in detecting low allele frequency somatic variants [23].

Targeted Sequencing Panels: Interrogate predefined sets of genes, variants, or biomarkers relevant to cancer pathways [23]. This is the most widely used NGS method in oncology research due to lower input requirements, compatibility with compromised samples like FFPE tissue, higher sequencing depth, and more manageable data analysis [24] [23].

RNA Sequencing: Facilitates transcriptome analysis to detect gene expression changes, fusion transcripts, and alternative splicing events [9] [23].

Table 1: Comparison of Major NGS Approaches in Cancer Research

| NGS Method | Genomic Coverage | Recommended Applications | Sample Requirements | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole Genome Sequencing | Entire genome | Discovery research, novel alteration identification, comprehensive profiling | High-quality, high-molecular weight DNA (typically 1μg) [23] | Most comprehensive, detects all variant types across genome | High cost, large data storage, complex analysis, not suitable for degraded samples |

| Exome Sequencing | Protein-coding regions (1-2% of genome) | Identifying coding variants, focused discovery | Moderate input requirements (typically 500 ng) [23] | Balances comprehensiveness with practicality, higher depth than WGS | Misses non-coding variants, uneven coverage, not recommended for FFPE [23] |

| Targeted Sequencing Panels | Selected genes/regions | Routine research, clinical trials, biomarker validation | Low input (minimum 10 ng), compatible with FFPE and degraded samples [23] | High depth, cost-effective, manageable data, ideal for limited samples | Limited to predefined targets, cannot discover novel genes outside panel |

| RNA Sequencing | Transcriptome | Gene expression, fusion detection, splicing analysis | Total RNA (500 ng–2 μg for whole transcriptome) [23] | Detects expressed variants, fusion transcripts, expression levels | RNA stability challenges, complex data normalization |

Sample Considerations for Optimal NGS Results

Sample quality and preparation critically impact NGS success. Different sample types present unique challenges and requirements for optimal sequencing results:

FFPE Tissue: The most common sample type in oncology research, but fixation causes cross-linking, strand breaks, and nucleic acid fragmentation [23]. DNA from FFPE is typically low molecular weight with fragments <300 bp, resulting in variable library yields and potential reduced data accuracy without proper methods [23]. Targeted amplicon sequencing is most reliable for FFPE due to compatibility with short fragments [23].

Fresh-Frozen Tissue: Provides the highest quality nucleic acids compatible with all NGS methods [23].

Liquid Biopsies: Utilize cell-free DNA (cfDNA) from blood or other fluids, with tumor DNA representing only a small fraction of total cfDNA [23]. This requires specialized ultra-deep targeted sequencing to sufficiently cover tumor DNA [23]. cfDNA consists of very short fragments that degrade rapidly, necessitating optimized collection, processing, and storage conditions [23].

Fine-Needle Aspirates and Core-Needle Biopsies: Limited samples best analyzed with targeted sequencing due to low input requirements [23]. Quality depends on cytopreparation method, with fresh or frozen samples preferred over formalin-fixed [23].

Tumor content is another critical consideration, with typical minimum requirements of 10-20% to avoid false-negative results [23]. Tumor enrichment techniques include macrodissection or pathologist-guided selection of cancer cell-rich areas [23].

Diagram 1: Comprehensive NGS Workflow for Cancer Research. This diagram illustrates the key steps in the NGS process, from sample collection through interpretation, highlighting critical decision points and methodology options.

Key Research Applications in Precision Oncology

Comprehensive Genomic Profiling for Actionable Alterations

NGS enables comprehensive genomic profiling that identifies actionable mutations across multiple cancer types, facilitating personalized treatment approaches. Research demonstrates that approximately 62.3% of tumor samples harbor actionable biomarkers identifiable through NGS, with tissue-agnostic biomarkers present in 8.4% of cases across diverse cancer types [25]. The clinical actionability of these findings is substantial, with real-world studies showing that 26.0% of patients harbor Tier I variants (strong clinical significance) and 86.8% carry Tier II variants (potential clinical significance) according to Association for Molecular Pathology classification [18].

In clinical implementation studies, NGS-based therapy led to measurable benefits, with 37.5% of patients achieving partial response and 34.4% achieving stable disease [18]. The median treatment duration was 6.4 months, demonstrating the meaningful clinical impact of NGS-guided treatment selection [18]. The prevalence of actionable alterations varies by cancer type, with highest rates observed in central nervous system tumors (83.6%), lung cancer (81.2%), and breast cancer (79.0%) [25].

Table 2: Prevalence of Actionable Biomarkers Across Major Cancer Types

| Cancer Type | Prevalence of Actionable Alterations | Most Common Actionable Alterations | Tumor-Agnostic Biomarker Prevalence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Central Nervous System Tumors | 83.6% [25] | IDH1/2, BRAF V600E, TERT promoter [22] | 8.4% across 26 cancer types [25] |

| Lung Cancer | 81.2% [25] | EGFR, ALK, ROS1, RET, KRAS [26] | 16.8% [25] |

| Breast Cancer | 79.0% [25] | PIK3CA, BRCA1/2, ERBB2, AKT/PTEN pathway [26] | Information not specified in search results |

| Colorectal Cancer | Information not specified in search results | KRAS, NRAS, BRAF, MSI-H [25] | 8.4% across 26 cancer types [25] |

| Prostate Cancer | Information not specified in search results | BRCA1/2, HRD, PTEN [25] | 8.4% across 26 cancer types [25] |

| Ovarian Cancer | Information not specified in search results | BRCA1/2, HRD [25] | 8.4% across 26 cancer types [25] |

Tumor-Agnostic Biomarker Discovery

NGS has been instrumental in identifying and validating tumor-agnostic biomarkers that enable treatment decisions based on molecular characteristics rather than tissue of origin [22]. Key tissue-agnostic biomarkers include:

NTRK Fusions: Occur in diverse cancer types including gastrointestinal cancers, gynecological, thyroid, lung, and pediatric malignancies [22]. First-generation TRK inhibitors like Larotrectinib demonstrate impressive efficacy with overall response rates of 79% across multiple trials [22].

RET Fusions: Present in less than 5% of all cancer patients, found in thyroid, lung, and breast cancers [22]. Selective RET inhibitors like Selpercatinib and Pralsetinib show pan-cancer efficacy with response rates of 43.9-57% in non-NSCLC or thyroid carcinomas [22].

Microsatellite Instability-High (MSI-H): Found in multiple cancer types including endometrial (5.9%), gastric (4.7%), and cancer of unknown primary (4%) [25]. MSI-H tumors show significantly higher tumor mutational burden compared to microsatellite stable tumors (median TMB 23.0 vs 5.15) [25].

High Tumor Mutational Burden (TMB-H): Defined as ≥10 mutations/megabase, found in 6.6% of samples across cancer types, with highest proportions in lung (15.4%), endometrial (11.8%), and esophageal (11.1%) cancers [25].

Homologous Recombination Deficiency (HRD): Observed in 34.9% of samples across cancer types, present in approximately 50% of breast, colon, lung, ovarian, and gastric tumors [25]. HRD-positive tumors exhibit significantly higher TMB compared to HRD-negative tumors [25].

Diagram 2: Tumor-Agnostic Biomarkers and Matched Therapies. This diagram illustrates key tissue-agnostic biomarkers detectable by NGS and their corresponding targeted therapeutic approaches.

Experimental Protocols for NGS Implementation

DNA Extraction and Library Preparation Protocol

Sample Requirements and Quality Control:

- Obtain FFPE tissue sections, fresh-frozen tissue, or liquid biopsy samples [23] [18]

- For FFPE samples: Use a sufficient number of slides (typically 5-10 sections of 5-10μm thickness) to meet input requirements [23]

- Ensure tumor content ≥20% through macro-dissection or pathologist review [23]

- Extract DNA using specialized kits (e.g., QIAamp DNA FFPE Tissue kit for FFPE samples) [18]

- Quantify DNA concentration using fluorescence-based methods (e.g., Qubit dsDNA HS Assay) rather than UV absorbance [23]

- Assess DNA purity (A260/A280 ratio between 1.7-2.2) and fragment size [18]

- Minimum input: 20 ng DNA for hybrid capture methods; 10 ng for targeted amplicon sequencing [23] [18]

Library Preparation Steps:

- Fragmentation: Fragment genomic DNA to 300 bp using physical, enzymatic, or chemical methods [9]

- Adapter Ligation: Attach platform-specific adapters to both ends of DNA fragments [9] [24]

- Barcoding: Add unique molecular barcodes to enable sample multiplexing [24]

- Library Amplification: Amplify library using PCR with adapter-specific primers [24]

- Quality Control: Assess library quantity and quality using quantitative PCR and fragment analysis (e.g., Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer) [9] [18]

- Target Enrichment: For targeted panels, use hybridization capture (e.g., Agilent SureSelectXT) or multiplex PCR approaches to enrich for genes of interest [24] [18]

Sequencing and Data Analysis Protocol

Sequencing Execution:

- Select appropriate sequencing platform based on required read length, throughput, and application [7]

- For targeted panels, sequence on platforms such as Illumina NextSeq 550Dx with recommended coverage >500x for somatic variant detection [18]

- Include both positive and negative controls in each sequencing run [27]

Bioinformatic Analysis Pipeline:

- Base Calling: Convert raw signal data to nucleotide sequences using platform-specific software [24]

- Read Alignment: Map sequence reads to reference genome (e.g., hg19) using aligners like BWA [7]

- Variant Calling:

- Variant Annotation: Annotate variants using SnpEff and filter against population databases (e.g., gnomAD) [18]

- Specialized Biomarker Analysis:

Quality Assurance Measures:

- Implement quality control at each analysis step, monitoring metrics including coverage uniformity, mapping rates, and duplicate reads [27]

- Validate variant calls using orthogonal methods when necessary [24]

- Classify variants according to established guidelines (e.g., AMP/ASCO/CAP standards) [18]

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for NGS in Cancer Genomics

| Reagent/Material | Function | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits | Isolation of high-quality DNA from various sample types | QIAamp DNA FFPE Tissue kit, specialized kits for different sample matrices [18] |

| Library Preparation Kits | Fragment processing, adapter ligation, library amplification | Illumina library prep kits, Agilent SureSelectXT for hybrid capture [18] |

| Target Enrichment Systems | Selection of genomic regions of interest | Multiplex PCR approaches, hybridization capture baits (e.g., for 544-gene panels) [18] |

| Sequencing Platforms | Massive parallel sequencing of prepared libraries | Illumina NextSeq 550Dx, platform-specific flow cells and reagents [18] |

| Quality Control Tools | Assessment of nucleic acid and library quality | Qubit dsDNA HS Assay, Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer, quantitative PCR [23] [18] |

| Bioinformatics Software | Data analysis, variant calling, interpretation | BWA alignment, Mutect2 variant calling, CNVkit, SnpEff annotation [18] |

| Reference Standards | Process validation and quality assurance | Cell line-derived controls, synthetic spike-in controls for variant detection [27] |

NGS technologies have become the cornerstone of precision oncology research, providing comprehensive genomic profiling that enables personalized cancer treatment strategies. The applications span from basic cancer biology research to clinical trial design and implementation, with demonstrated utility in identifying actionable alterations, guiding targeted therapy, and discovering novel biomarkers. The continued refinement of NGS methodologies, analytical pipelines, and quality management systems will further enhance the capabilities of cancer researchers and clinicians to deliver on the promise of precision oncology.

As NGS technologies evolve and integrate with emerging approaches like single-cell sequencing, spatial transcriptomics, and artificial intelligence, their transformative impact on cancer research and patient care will continue to accelerate. The standardized protocols and analytical frameworks presented here provide a foundation for rigorous implementation of NGS in precision oncology research initiatives.

The comprehensive molecular characterization of human cancers has been revolutionized by large-scale, collaborative genomics initiatives. The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and the International Cancer Genome Consortium (ICGC) represent two landmark programs that have systematically cataloged genomic alterations across thousands of tumors, creating foundational resources for cancer research [28] [29]. These initiatives emerged in the mid-2000s, leveraging advances in next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies to generate multi-dimensional datasets encompassing genomic, epigenomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic data [30] [31]. The primary objective of these programs was to create a comprehensive map of cancer genomic abnormalities, enabling researchers to identify novel cancer drivers, understand molecular subtypes, and discover potential therapeutic targets.

The scale of these projects is unprecedented in biomedical research. TCGA molecularly characterized over 20,000 primary cancer and matched normal samples spanning 33 cancer types, generating over 2.5 petabytes of publicly available data [28]. Similarly, the ICGC originally aimed to define the genomes of 25,000 primary untreated cancers, with subsequent initiatives expanding this scope [29]. These programs have transitioned cancer research from a single-gene to a systems biology approach, facilitating the discovery of complex molecular interactions and networks that drive oncogenesis. The lasting impact of these resources continues to grow as researchers worldwide utilize these datasets to address fundamental questions in cancer biology and therapeutic development.

The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) Program

The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) was launched in 2006 as a joint effort between the National Cancer Institute (NCI) and the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) [28]. This landmark program employed a coordinated team science approach to comprehensively characterize the molecular landscape of tumors through multiple analytical platforms. TCGA began with a three-year pilot project focusing on glioblastoma multiforme (GBM), lung squamous cell carcinoma (LUSC), and ovarian serous cystadenocarcinoma (OV), which demonstrated the feasibility and value of large-scale cancer genomics [30]. The success of this pilot phase led to the full-scale project from 2009 to 2015, ultimately encompassing 33 different cancer types from 11,160 patients [30].

A key innovation of TCGA was its systematic approach to sample acquisition and data generation. The program established standardized protocols for sample collection, nucleic acid extraction, and molecular analysis to ensure data consistency across participating institutions [28]. Each tumor underwent comprehensive molecular profiling, including whole-exome sequencing, DNA methylation analysis, transcriptomic sequencing (RNA-seq), and in some cases, whole-genome sequencing and proteomic analysis. This multi-platform approach enabled researchers to examine multiple layers of molecular regulation and their interactions in cancer development and progression.

To maximize the research utility of TCGA data, significant efforts were made to curate high-quality clinical information alongside molecular profiles. The TCGA Pan-Cancer Clinical Data Resource (TCGA-CDR) was developed to provide standardized clinical outcome endpoints across all TCGA cancer types [30]. This resource includes four major clinical outcome endpoints: overall survival (OS), disease-specific survival (DSS), disease-free interval (DFI), and progression-free interval (PFI). The TCGA-CDR addresses challenges in clinical data integration arising from the democratized nature of original data collection, providing researchers with carefully curated clinical correlates for genomic findings.

The clinical utility of TCGA data is enhanced through the Genomic Data Commons (GDC), which serves as a unified repository for these datasets [32]. Launched in 2016 and recently upgraded to GDC 2.0, this platform provides researchers with web-based tools for data analysis and visualization directly within the portal, eliminating the need for extensive bioinformatics expertise or specialized analysis tools [32]. The GDC represents a critical evolution in data sharing, making TCGA data accessible to a broader research community and enabling real-time exploration of complex genomic datasets.

Table 1: Key Molecular Data Types in TCGA

| Data Type | Description | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Whole-Exome Sequencing | Sequencing of protein-coding regions | Identification of somatic mutations in genes |

| RNA Sequencing | Transcriptome profiling | Gene expression analysis, fusion gene detection |

| DNA Methylation Array | Epigenomic profiling | Analysis of promoter methylation and gene silencing |

| Copy Number Variation | Genomic copy number analysis | Identification of amplifications and deletions |

| Clinical Data | Patient outcomes and treatment history | Clinical-genomic correlation studies |

Analytical Methods and Computational Tools

TCGA employed sophisticated computational pipelines for data processing and variant calling. For mutation detection, multiple algorithms were utilized including VarScan and SomaticSniper for somatic single nucleotide variants (SNVs), Pindel for insertion/deletion detection, and specialized tools for copy number alteration (CNA) and structural variation (SV) identification [33]. The alignment of sequencing data to reference genomes and subsequent variant calling followed stringent quality control measures to ensure data reliability.

The analytical approaches developed for TCGA data addressed several unique challenges in cancer genomics. Normalization procedures were implemented to correct for GC content bias and mapping biases inherent in NGS data [33]. For copy number analysis, methods such as GC-based coverage normalization and correction for mapping bias were applied to unique read depth calculations [33]. The integration of multiple data types required specialized statistical methods and visualization tools, leading to the development of resources like the Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV) for exploring large genomic datasets [33].

International Cancer Genome Consortium (ICGC)

Consortium Structure and Global Collaboration

The International Cancer Genome Consortium (ICGC) was established in 2008 as a global initiative to coordinate large-scale cancer genome studies across multiple countries and institutions [29] [31]. Unlike TCGA's primarily U.S.-focused effort, ICGC was designed as a federated network of research programs following common standards for data generation and sharing. This international approach enabled the characterization of cancer genomes across diverse populations and healthcare systems, capturing a broader spectrum of genomic variation and cancer subtypes.

The original ICGC initiative, known as the 25k Project, aimed to comprehensively analyze 25,000 primary untreated cancers across 50 different cancer types [29]. To date, this effort has produced more than 20,000 tumor genomes for 26 cancer types, with participating countries including Canada, United Kingdom, Germany, Japan, China, and Australia, among others [29]. The distributed nature of ICGC required sophisticated informatics infrastructure for data harmonization, with central portals facilitating data access while raw data remained stored at contributing institutions. This model demonstrated the feasibility of international collaboration in big data cancer research while respecting national data governance policies.

Key Initiatives: PCAWG and ARGO

The Pan-Cancer Analysis of Whole Genomes (PCAWG) project represents a landmark achievement of the ICGC. Commencing in 2013, this international collaboration analyzed more than 2,600 whole-cancer genomes from ICGC and TCGA [29] [31]. Unlike previous efforts focused primarily on protein-coding regions, PCAWG comprehensively explored somatic and germline variations in both coding and non-coding regions, with specific emphasis on cis-regulatory sites, non-coding RNAs, and large-scale structural alterations. The project published a suite of 23 papers in Nature and affiliated journals in February 2020, reporting major advances in understanding cancer driver mutations, structural variations, and mutational processes [31].

Building on these achievements, ICGC has evolved into its next phase known as ICGC ARGO (Accelerating Research in Genomic Oncology) [34]. This initiative aims to analyze specimens from 100,000 cancer patients with high-quality clinical data to address outstanding questions in cancer genomics and treatment. As of recent data releases, ICGC ARGO has reached significant milestones with over 5,500 donors available in the data platform and more than 63,000 committed donors representing 20 tumor types [34]. The ARGO platform emphasizes uniform analysis of specimens with comprehensive clinical annotation, enabling researchers to correlate genomic findings with detailed treatment responses and patient outcomes.

Table 2: ICGC Initiative Overview

| Initiative | Primary Focus | Key Achievements |

|---|---|---|

| 25k Project | Comprehensive analysis of 25,000 primary untreated cancers | >20,000 tumor genomes for 26 cancer types [29] |

| PCAWG | Whole-genome analysis of 2,600+ cancers | 23 companion papers; non-coding driver mutations [31] |

| ICGC ARGO | Clinical translation with 100,000 cancer patients | 5,528 donors in current release; 20 tumor types [34] |

Data Generation and Harmonization

ICGC implemented rigorous technical standards for data generation across participating centers. The PCAWG project alone collected genome data from 2,834 donors, with 2,658 passing stringent quality assurance measures [31]. Mean read coverage was approximately 39× for normal samples and bimodal (38×/60×) for tumor samples, ensuring sufficient depth for variant detection [31]. To address computational challenges in processing nearly 5,800 whole genomes, the consortium utilized cloud computing to distribute alignment and variant calling across 13 data centers on 3 continents [31].

Variant calling in ICGC employed multiple complementary approaches to maximize sensitivity and specificity. For the PCAWG project, three established pipelines were used to call somatic single-nucleotide variations (SNVs), small insertions and deletions (indels), copy-number alterations (CNAs), and structural variants (SVs) [31]. The consensus approach significantly improved calling accuracy, particularly for variants with low allele fractions originating from tumor subclones. Benchmarking against validation datasets demonstrated 95% sensitivity and 95% precision for SNVs, with lower but substantial accuracy for more challenging variant types like indels (60% sensitivity, 91% precision) [31].

Next-Generation Sequencing Methodologies

Core NGS Technologies and Platform Comparisons

Next-generation sequencing technologies form the methodological foundation for modern cancer genomics initiatives. NGS represents a revolutionary leap from traditional Sanger sequencing, enabling massive parallel sequencing of millions of DNA fragments simultaneously [9]. This technological advancement has dramatically reduced the time and cost associated with comprehensive genomic analysis, making large-scale projects like TCGA and ICGC feasible. The core principle of NGS involves fragmenting genomic DNA, attaching universal adapters, amplifying individual fragments, and simultaneously sequencing millions of these clusters through cyclic synthesis with fluorescently labeled nucleotides.