PDX vs. Organoid Models: A Comparative Analysis of Predictive Value in Oncology Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of Patient-Derived Xenograft (PDX) and Patient-Derived Organoid (PDO) models, two transformative technologies in preclinical oncology research.

PDX vs. Organoid Models: A Comparative Analysis of Predictive Value in Oncology Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of Patient-Derived Xenograft (PDX) and Patient-Derived Organoid (PDO) models, two transformative technologies in preclinical oncology research. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles, methodological applications, and optimization strategies for both platforms. We critically evaluate their capacity to predict clinical drug response, examining evidence from multiple cancer types including gastrointestinal, ovarian, and prostate cancers. The analysis synthesizes current data on model fidelity, throughput, cost, and clinical correlation, offering a strategic framework for model selection to enhance the predictive power and efficiency of cancer drug discovery and personalized medicine approaches.

Understanding PDX and Organoid Models: Core Principles and Tumor Biology Preservation

Model Fundamentals and Establishment

Patient-Derived Xenograft (PDX) Models are established by implanting fresh fragments of human patient tumors directly into immunocompromised mice [1] [2]. These models serve as in vivo surrogates, allowing the study of tumor behavior within a living organism. The process involves several key steps: tumor tissue is acquired from surgery or biopsy, cut into small pieces, and then implanted into mice, typically subcutaneously, orthotopically (into the corresponding mouse organ), or under the renal capsule [1] [3]. To prevent rejection of the human tissue, highly immunodeficient mouse strains such as NOD-SCID or NSG mice are used [1] [3]. The engrafted tumors are then passaged in mice to expand the model [1].

Organoids, or Patient-Derived Organoids (PDOs), are three-dimensional (3D) in vitro systems grown from stem cells or tumor cells in a lab dish [4] [5]. They are designed to self-organize and recapitulate the structure and function of the original tissue [4]. Establishment involves digesting a patient tumor sample into small fragments or single cells, which are then embedded in an extracellular matrix (like Matrigel) and fed with a specialized culture medium containing growth factors necessary for stem cell survival and proliferation [6] [4]. This process allows the cells to grow and form 3D structures that mimic key aspects of the original tumor [5].

Comparative Strengths and Limitations

The choice between PDX and organoid models is guided by their distinct advantages and drawbacks, which are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Strengths and Limitations of PDX and Organoid Models

| Feature | Patient-Derived Xenograft (PDX) | Patient-Derived Organoid (PDO) |

|---|---|---|

| Physiological Context | In vivo; preserves some tumor-stroma interactions and allows study of systemic drug effects like pharmacokinetics [1] [7]. | In vitro; largely lacks a complete tumor microenvironment (e.g., functional blood vessels, immune system) though co-culture methods are improving this [3] [8]. |

| Predictive Value | High; demonstrates strong correlation with patient clinical responses, making them a gold standard for preclinical drug testing [2] [7]. | High; shows a 68% Positive Predictive Value (PPV) and 78% Negative Predictive Value (NPV) for therapy response in colorectal cancer [6]. |

| Tumor Heterogeneity | Retains the intratumor heterogeneity and spatial architecture of the original patient tumor [1]. | Retains tumor cell heterogeneity but may lose some spatial context and select for certain cell populations over time [4] [8]. |

| Throughput & Scalability | Low to medium; time-consuming (months) and expensive to establish and maintain, limiting high-throughput screening [3]. | High; can be established and expanded in 1-2 weeks, suitable for high-throughput drug screening and biobanking [6] [8]. |

| Technical & Cost Considerations | High cost due to animal maintenance; requires specialized facilities for immunodeficient mice; low engraftment rate for some cancer types [2] [3]. | Cost-effective; more affordable than PDX; technically less demanding but requires optimization of culture media for different cancer types [8]. |

| Human Microenvironment | Lacks a human immune system (unless using humanized mice), and mouse stroma eventually replaces human stroma [1] [3]. | Enables co-culture with patient-specific immune cells to study immunotherapy and reconstruct human tumor-immune interactions [8] [9]. |

Experimental Workflows

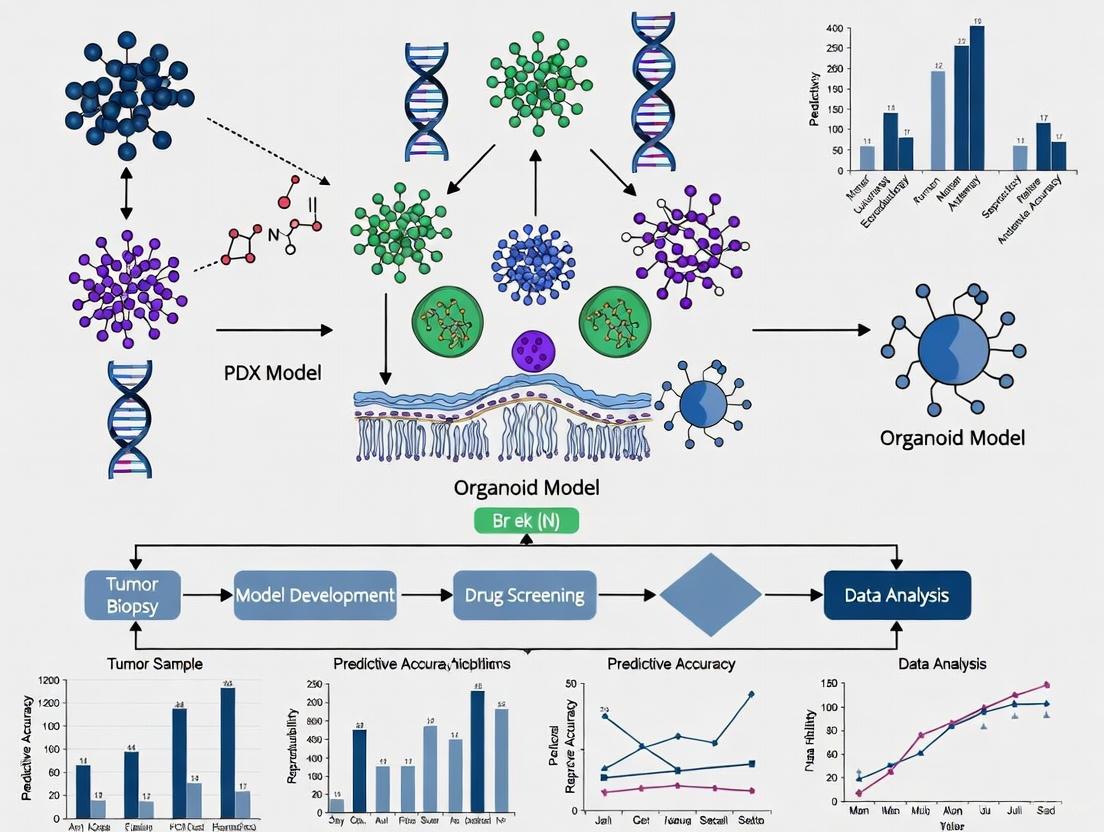

The processes for establishing and utilizing these models differ significantly. The following diagrams outline the core workflows.

Diagram: PDX Establishment and Application Workflow

Diagram: Organoid Establishment and Application Workflow

Quantitative Predictive Performance Data

A critical measure of a model's value is its ability to accurately predict patient responses. The table below summarizes performance data for organoid models from a systematic review in colorectal cancer.

Table 2: Predictive Performance of Colorectal Cancer Organoids in Therapy Response [6]

| Therapy Category | Predictive Metric | Performance Value |

|---|---|---|

| Chemotherapy, Targeted Drugs, & Radiotherapy | Positive Predictive Value (PPV) | 68% |

| Negative Predictive Value (NPV) | 78% | |

| Illustrative Drug: 5-Fluorouracil (5-FU) | Organoid Response predicts Patient Non-response | High Accuracy (Specificity >95% in one study [6]) |

For PDX models, while specific NPV/PPV values are not provided in the search results, multiple studies confirm a high degree of correlation between drug responses in PDX models and the clinical outcomes of the donor patients, solidifying their role in preclinical drug development [2] [7].

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful establishment and experimentation with these models rely on a suite of specialized reagents.

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for PDX and Organoid Research

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Model Application |

|---|---|---|

| Immunodeficient Mice (e.g., NSG, NOG) | Host for human tumor tissue implantation; prevents graft rejection. | PDX |

| Extracellular Matrix (e.g., Matrigel) | Provides a 3D scaffold that supports cell growth, polarization, and organization. | Organoid |

| Specialized Culture Media | Chemically defined medium containing niche factors (e.g., WNT, R-spondin) for stem cell maintenance. | Organoid |

| Tumor Dissociation Kits | Enzymatic blends (e.g., collagenase) for breaking down solid tumor tissue into cells/fragments. | PDX & Organoid |

| Cryopreservation Media | Allows long-term storage and biobanking of established PDX tumors or organoid lines. | PDX & Organoid |

PDX and organoid models are complementary tools that address different research needs. PDX models are the premier in vivo system for studying tumors in a whole-body context, making them indispensable for late-stage preclinical validation of drug efficacy, resistance mechanisms, and metastatic processes [1] [7]. In contrast, organoids are a powerful high-throughput in vitro platform ideal for large-scale drug screening, personalized therapy prediction, and genetic manipulation, all within a clinically relevant timeline [6] [8] [9].

The future of cancer modeling lies in the convergence of these systems. Emerging approaches include using PDX-derived organoids to expand limited PDX material and creating more complex humanized PDX models by engrafting a human immune system to effectively evaluate immunotherapy [3]. As both technologies evolve, they will continue to enhance the predictive power of cancer research and accelerate the development of novel therapeutics.

The Critical Role of Cancer Stem Cells in Maintaining Tumor Heterogeneity

Tumor heterogeneity remains a significant challenge in oncology, driving disease progression, metastasis, and therapeutic resistance. Cancer stem cells (CSCs) are now recognized as pivotal contributors to this heterogeneity through their self-renewal and differentiation capacities. This review examines how patient-derived xenograft (PDX) and organoid models uniquely capture CSC-driven heterogeneity and their predictive value in preclinical research. We provide a comparative analysis of these models' abilities to maintain CSC populations, preserve tumor architecture, and predict clinical drug responses. The integration of these advanced models represents a transformative approach for drug development and personalized cancer therapy, enabling more accurate simulation of patient-specific tumor biology and treatment outcomes.

Tumor heterogeneity presents a fundamental obstacle in cancer treatment, contributing to variable therapeutic responses and eventual treatment failure. This diversity within tumors arises from genetic, epigenetic, and microenvironmental variations, with cancer stem cells (CSCs) serving as key regulators through their capacity for self-renewal and differentiation into multiple cell lineages [10]. CSCs not only initiate and maintain tumors but also drive metastasis and confer resistance to conventional therapies, making them critical targets for therapeutic development.

The emergence of sophisticated preclinical models has revolutionized our ability to study CSC biology and tumor heterogeneity. Patient-derived xenografts (PDXs), established by transplanting human tumor fragments into immunodeficient mice, preserve the original tumor's stromal components and cellular diversity [11] [12]. Conversely, patient-derived organoids (PDOs) are three-dimensional (3D) in vitro cultures that self-organize from stem cells—including CSCs—to recapitulate the structural and functional characteristics of original tumors [13] [10]. Both models offer distinct advantages for investigating CSC maintenance and functionality within heterogeneous tumor populations.

This review provides a comprehensive comparison of PDX and organoid models in their capacity to maintain tumor heterogeneity through CSC preservation. We evaluate their applications in drug screening, personalized medicine, and preclinical validation, highlighting how each model system captures different aspects of CSC biology. Understanding the strengths and limitations of these platforms is essential for advancing cancer research and developing more effective, heterogeneity-informed treatment strategies.

Fundamentals of Cancer Stem Cells and Tumor Heterogeneity

Biological Mechanisms of Cancer Stem Cells

CSCs constitute a small subpopulation within tumors that possess stem cell-like properties, including self-renewal capability, multipotency, and enhanced survival mechanisms. These cells drive tumor initiation, progression, and recurrence by generating diverse daughter cells through asymmetric division [10]. The CSC hypothesis posits that hierarchical organization exists within tumors, with CSCs at the apex maintaining the heterogeneous cellular composition of the malignancy.

CSCs reside in specialized microenvironmental niches that regulate their behavior through complex signaling networks. Key pathways involved in CSC maintenance include Wnt/β-catenin, Notch, Hedgehog, and EGFR-RAS-RAF-MAPK cascades [13] [12]. These pathways not only control CSC self-renewal and differentiation but also contribute to therapeutic resistance mechanisms. CSCs demonstrate enhanced DNA repair capacity, increased expression of drug efflux transporters, and resistance to apoptosis, making them particularly resilient to conventional chemotherapy and radiotherapy [14].

Technical Approaches for CSC Identification and Isolation

Several methodologies enable the identification and isolation of CSCs for experimental study:

- Cell Surface Marker Expression: Specific markers vary by cancer type but commonly include CD44, CD133, CD24, and epithelial-specific antigen (ESA) [10]. These markers facilitate CSC isolation via fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) or magnetic-activated cell sorting for downstream applications.

- Functional Assays: The gold standard for CSC validation includes sphere-forming assays under non-adherent conditions, in vivo limiting dilution transplantation assays, and dye exclusion assays demonstrating side population phenotype via Hoechst 33342 efflux [14].

- Transcriptional Profiling: Detection of stemness-associated transcription factors such as OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, and MYC provides additional confirmation of CSC identity [10].

The successful maintenance of these CSC properties in experimental models is crucial for preserving tumor heterogeneity in preclinical studies.

Comparative Analysis of PDX and Organoid Models

Model Establishment and Technical Specifications

Table 1: Establishment Protocols and Success Rates for PDX and Organoid Models

| Parameter | Patient-Derived Xenografts (PDX) | Patient-Derived Organoids (PDO) |

|---|---|---|

| Source Material | Surgical specimens, biopsy fragments | Surgical specimens, biopsies, malignant effusions, circulating tumor cells |

| Establishment Time | 3-6 months | 2-8 weeks |

| Success Rate | Variable (15-80%, tumor-type dependent) | 70-90% for certain carcinomas [15] |

| Key Culture Components | Immunodeficient mice, Matrigel | Defined medium with growth factors (EGF, Noggin, R-spondin), extracellular matrix (Matrigel) [13] |

| Cost Considerations | High (animal maintenance, personnel) | Moderate (culture reagents, matrix) |

| Throughput Capacity | Low to moderate | High to very high |

Fidelity in Preserving Tumor Heterogeneity

Table 2: Model Performance in Capturing Tumor Heterogeneity and CSC Properties

| Feature | PDX Models | Organoid Models |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic Stability | High fidelity maintained over early passages, potential for mouse stromal replacement over time | High short-term genetic stability, clonal selection possible in long-term culture [13] |

| CSC Maintenance | Preserves native CSC niche and hierarchy | Maintains self-renewing capacity through culture conditions supporting stemness [10] |

| Cellular Heterogeneity | Recapitulates original tumor cellular diversity | Maintains intra-tumoral heterogeneity, though stromal components may be lost [11] |

| Microenvironment | Intact human stroma initially, gradually replaced by mouse stroma | Limited native microenvironment, requires co-culture systems for immune/stromal cells [13] |

| Histopathological Concordance | High architectural similarity to original tumor | Maintains histologic features but may lack organizational context [15] |

PDX models demonstrate superior preservation of the tumor microenvironment, including stromal components and vascular networks, which are crucial for maintaining CSC niches. A comparative study of ovarian clear cell carcinoma models found that PDX and PDTO models were able to recapitulate patient tumor heterogeneity, while cell lines failed to maintain this diversity [11]. This preservation extends to molecular characteristics, with PDXs maintaining genomic stability across passages when carefully managed.

Organoid models excel in maintaining epithelial heterogeneity and CSC functionality through specialized culture conditions. Lung cancer organoids derived from malignant serous effusions have demonstrated success rates exceeding 80% while faithfully reflecting the original sample's pathologic and genomic features [15]. These models can capture spatial and temporal heterogeneity, making them valuable for studying clonal evolution and CSC dynamics in response to therapeutic pressures.

Predictive Value in Drug Development and Personalized Medicine

Table 3: Predictive Performance in Preclinical and Clinical Applications

| Application | PDX Models | Organoid Models |

|---|---|---|

| Drug Screening | Moderate throughput, strong clinical correlation | High throughput, emerging clinical validation [15] [12] |

| Clinical Response Prediction | High concordance (85-90%) for certain cancer types | Promising results (80-90% concordance) in multiple studies [15] [11] |

| Therapeutic Timeline | Too slow for real-time clinical decisions (months) | Potentially clinically actionable timeframe (weeks) [15] |

| Personalized Medicine Applications | Limited by establishment time and cost | Promising for biobanking and individualized therapy testing [13] |

PDX models have established a strong track record in predicting clinical responses, particularly for targeted therapies. Their preservation of tumor-stroma interactions enables more accurate modeling of drug penetration and metabolism. However, the extended timeline for PDX establishment (3-6 months) often precludes their use in guiding first-line therapy decisions for individual patients.

Organoid models offer accelerated testing timelines compatible with clinical decision-making. A landmark study on lung cancer organoids demonstrated that LCO-based drug sensitivity tests (LCO-DSTs) accurately predict clinical response to both chemotherapy and targeted therapy in patients with advanced lung cancer [15]. Similarly, colorectal cancer organoids have shown high concordance with patient responses to standard chemotherapies like 5-FU and FOLFOX [12]. The scalability of organoid platforms enables high-throughput drug screening while maintaining patient-specific heterogeneity.

Experimental Protocols for CSC and Heterogeneity Analysis

Organoid Establishment from Patient Tumors

Sample Processing and Initiation:

- Sample Collection: Obtain tumor tissue via surgical resection, core needle biopsy, or malignant effusion (pleural, ascitic, or pericardial fluid) [15] [14]. Process within 1-2 hours of collection for optimal viability.

- Mechanical Dissociation: Mince tissue into 1-3 mm³ fragments using sterile surgical scissors or scalpels in cold Advanced DMEM/F12 medium.

- Enzymatic Digestion: Incubate tissue fragments with collagenase/hyaluronidase solution (e.g., Tumor Dissociation Kit, Miltenyi Biotec) at 37°C with agitation for 30 minutes to 2 hours based on tissue density [11] [14].

- Cell Separation: Pass digested suspension through 70-100 μm cell strainers to obtain single cells and small clusters. Centrifuge at 300-500 × g for 5 minutes and resuspend in organoid basal medium.

Organoid Culture and Maintenance:

- Matrix Embedding: Mix cell pellet with extracellular matrix (Matrigel, BME, or Geltrex) at appropriate dilution (typically 1:1 to 1:3 ratio). Plate 10-50 μL drops in pre-warmed culture plates and polymerize at 37°C for 20-30 minutes [14].

- Medium Formulation: Overlay with organoid culture medium containing essential supplements:

- Base Medium: Advanced DMEM/F12 with HEPES and GlutaMAX

- Growth Factors: EGF (50 ng/mL), FGF-10 (20 ng/mL), FGF-basic (1-10 ng/mL)

- Pathway Modulators: R-spondin (Wnt agonist), Noggin (BMP inhibitor), A-83-01 (TGF-β inhibitor)

- Additional Supplements: B27, N-Acetylcysteine, Nicotinamide, Prostaglandin E2

- ROCK Inhibitor: Y-27632 (10 μM) for initial 2-3 days to prevent anoikis [11] [14]

- Passaging: Dissociate mature organoids (7-21 days) using mechanical disruption or enzymatic treatment with TrypLE Express. Replate dissociated cells in fresh matrix at appropriate dilution (typically 1:3 to 1:10 split ratio).

PDX Establishment and Propagation

Initial Implantation:

- Sample Preparation: Process fresh tumor tissue within 1 hour of resection. Minimally dissect into 2-4 mm³ fragments in cold, serum-free medium preserving tissue architecture.

- Host Selection: Utilize immunocompromised mouse strains (NSG, NOG, or nude mice) aged 6-8 weeks. Anesthetize animals following institutional guidelines.

- Surgical Implantation: For subcutaneous models, create small dorsal incision and insert single tumor fragment into flank pocket. For orthotopic models, implant directly into corresponding organ of origin [11].

- Post-operative Care: Monitor animals for tumor growth, general health, and potential complications according to ethical guidelines.

Model Propagation and Cryopreservation:

- Passage Timing: Harvest tumors at 1000-1500 mm³ volume (typically 2-6 months post-implantation) to maintain exponential growth phase.

- Fragment Preparation: Aseptically process harvested tumor, removing necrotic areas. Prepare fragments as for initial implantation.

- Serial Passage: Implant prepared fragments into new host animals (typically 3-5 mice per line) to maintain model.

- Biobanking: Cryopreserve early passage fragments in DMSO/FBS solution using controlled-rate freezing for long-term storage in liquid nitrogen [11].

CSC Functional Assays in Model Systems

Sphere Formation Assay:

- Single-Cell Preparation: Dissociate PDX tumors or organoids to single-cell suspension using enzymatic digestion and mechanical disruption.

- Culture Conditions: Plate 500-10,000 viable cells/mL in ultra-low attachment plates with serum-free medium supplemented with EGF, bFGF, and B27.

- Quantification: Count spheres >50 μm after 7-21 days using inverted microscopy. Calculate sphere-forming efficiency as (number of spheres/number of cells seeded) × 100% [14].

In Vivo Limiting Dilution Assay:

- Cell Preparation: Generate single-cell suspensions from PDX or organoid models with confirmed viability >90%.

- Cell Dilutions: Prepare serial dilutions (e.g., 10,000, 1,000, 100, 10 cells) in PBS:Matrigel mixture (1:1).

- Implantation: Inject each dilution subcutaneously into immunocompromised mice (5-10 animals per dilution).

- Tumor Incidence Monitoring: Palpate weekly for 8-16 weeks for tumor formation. Calculate CSC frequency using extreme limiting dilution analysis (ELDA) software [10].

Drug Response Assays:

- Treatment Planning: Plate organoids or PDX-derived cells in 96-well format. Include viability controls and reference compounds.

- Compound Exposure: Add serially diluted therapeutics (typically 5-8 concentrations) after 24-72 hours of culture. Include vehicle controls.

- Endpoint Analysis: Assess viability after 5-7 days using CellTiter-Glo 3D or similar ATP-based assays. Calculate IC₅₀ values and generate dose-response curves [15] [11].

- Heterogeneity Assessment: Analyze single-cell responses via flow cytometry, imaging, or single-cell RNA sequencing to evaluate effects on CSC subpopulations.

Research Reagent Solutions for CSC and Heterogeneity Studies

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for CSC and Tumor Heterogeneity Investigations

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Extracellular Matrices | Matrigel, BME, Cultrex, synthetic PEG hydrogels | 3D structural support for organoid growth and CSC niche maintenance [13] |

| Stem Cell Media Supplements | B27, N2, N-Acetylcysteine, Recombinant EGF, FGF, R-spondin, Noggin | Creation of stem cell-supportive culture conditions for CSC maintenance [13] [14] |

| Cell Dissociation Reagents | Collagenase/Hyaluronidase, TrypLE, Accutase, Dispase | Tissue processing and organoid passaging while preserving cell viability [11] [14] |

| CSC Marker Antibodies | Anti-CD44, Anti-CD133, Anti-CD24, Anti-ESA | Identification and isolation of CSC populations via FACS or immunofluorescence |

| Pathway Inhibitors | Y-27632 (ROCK inhibitor), A-83-01 (TGF-β inhibitor), LGK974 (Porcupine inhibitor) | Modulation of signaling pathways critical for CSC self-renewal and differentiation [11] [14] |

| Viability Assays | CellTiter-Glo 3D, MTS, CCK-8, Live-Dead staining | Assessment of treatment responses and CSC survival in heterogeneous cultures [15] [13] |

Signaling Pathways in Cancer Stem Cell Maintenance

Figure 1: Key signaling pathways regulating cancer stem cell maintenance and function. These pathways represent critical therapeutic targets for eliminating CSCs and overcoming tumor heterogeneity. The Wnt/β-catenin pathway promotes self-renewal and proliferation, while Notch signaling balances self-renewal with differentiation decisions. Hedgehog signaling influences both self-renewal and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), a process linked to metastatic potential. EGFR-RAS signaling drives proliferation and contributes to therapy resistance, while TGF-β-SMAD signaling regulates EMT and therapeutic resistance programs [13] [12] [10]. Successful CSC-targeted therapies must address these interconnected pathways to effectively combat tumor heterogeneity.

Future Perspectives and Concluding Remarks

The integration of PDX and organoid models represents a powerful approach for advancing CSC research and addressing tumor heterogeneity in drug development. While each model offers distinct advantages, their complementary applications provide a more comprehensive understanding of CSC biology. PDX models maintain physiological microenvironmental contexts crucial for CSC regulation, while organoid platforms enable scalable experimentation and rapid clinical translation.

Future directions in this field include the development of more sophisticated microenvironmental reconstitution in organoid systems through co-culture with immune cells, fibroblasts, and vascular components [13]. Additionally, the integration of multi-omics technologies with functional drug testing in these models will enhance our understanding of heterogeneity-driven treatment resistance. The emerging "Organoid Plus and Minus" framework, which combines technological augmentation with culture system refinement, shows promise for improving screening accuracy and physiological relevance [16].

Advanced engineering approaches such as microfluidic organ-on-chip platforms that incorporate fluid flow, mechanical forces, and multi-tissue interfaces offer exciting opportunities to model CSC niches more accurately [12]. These systems can potentially bridge the gap between simplified organoid cultures and complex in vivo PDX models. Furthermore, the application of artificial intelligence and machine learning to analyze heterogeneity patterns and predict drug responses across model systems will accelerate therapeutic discovery [16].

As these technologies evolve, standardization of culture protocols, validation across diverse cancer types, and establishment of large-scale biobanks will be critical for broader implementation. The ongoing refinement of PDX and organoid models promises to enhance their predictive value in clinical translation, ultimately enabling more effective targeting of CSCs and overcoming tumor heterogeneity in cancer treatment.

In conclusion, both PDX and organoid models provide invaluable tools for studying the critical role of CSCs in maintaining tumor heterogeneity. Their continued development and integration into drug discovery pipelines will facilitate the creation of more effective therapeutic strategies that address the fundamental challenges of cancer heterogeneity, moving us closer to personalized medicine approaches that can overcome treatment resistance and improve patient outcomes.

Patient-derived xenograft (PDX) and patient-derived organoid (PDO) models are foundational tools in precision oncology, enabling the study of tumor biology and the prediction of patient responses to therapy. A model's utility in both basic research and clinical decision-making hinges on its ability to faithfully recapitulate the histopathological and genomic complexity of the original patient tumor. This guide provides an objective, data-driven comparison of PDX and PDO models, evaluating their performance in retaining key tumor characteristics and their application in predictive drug response studies. The analysis is framed within the context of a broader thesis comparing the predictive value of these avatar models, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a clear overview of their respective strengths and limitations.

At a Glance: Comparing PDX and PDO Model Fidelity

The following table summarizes the core characteristics of PDX and PDO models, providing a high-level comparison of their performance in retaining original tumor features.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of PDX and PDO Models

| Characteristic | Patient-Derived Xenografts (PDX) | Patient-Derived Organoids (PDO) |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Principle | Implantation of human tumor tissue into immunocompromised mice [17] [7] | 3D in vitro culture of patient tumor cells in defined matrices [17] [18] |

| Histopathological Architecture | Retains original histological architecture and stromal components [7] [19] | Recapitulates key architectural and molecular features [20] [18] |

| Cellular Heterogeneity | Preserves clonal diversity and tumor heterogeneity [21] [22] | Maintains cellular heterogeneity of the original tumor [20] [23] |

| Tumor Microenvironment (TME) | Retains human tumor stroma and interacts with mouse host components; lacks human adaptive immune system [17] [21] | Lacks native vascular and complex stromal complexity; can be co-cultured with immune cells [17] [18] |

| Ethical & Financial Burden | High (extensive animal use, time-consuming, costly) [17] [24] | Lower (in vitro culture, amenable to high-throughput screening) [17] [24] |

| Key Limitation | Mouse-specific evolution and genetic drift over passages [17] [22] | Inability to model tumor-stroma and immune interactions natively [17] [18] |

Quantitative Fidelity Assessment: A Meta-Analysis Perspective

A recent systematic review and meta-analysis directly compared the performance of PDX and PDO models in predicting patient responses to anti-cancer therapy. The study analyzed 411 patient-model pairs (267 PDX, 144 PDO) from solid tumors. The quantitative findings are summarized below.

Table 2: Predictive Performance of PDX and PDO Models from Meta-Analysis

| Performance Metric | PDX Models | PDO Models | Overall Concordance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Response Concordance | No significant difference from PDO | No significant difference from PDX | 70% [17] [24] |

| Sensitivity & Specificity | Comparable to PDO [24] | Comparable to PDX [24] | Not Specified |

| Predictive Value (PPV/NPV) | Comparable to PDO [24] | Comparable to PDX [24] | Not Specified |

| Association with Patient PFS | Association found only in low bias-risk pairs [17] | Patients with responding PDOs had prolonged PFS [17] | Not Applicable |

This comprehensive analysis suggests that PDOs perform similarly to PDX models in predicting matched-patient treatment response, while offering advantages in scalability and reduced ethical burden [17] [24].

Experimental Protocols for Model Establishment and Validation

To critically assess the data generated from these models, it is essential to understand their establishment and the rigorous validation processes required to confirm their fidelity.

Protocol for PDX Model Establishment

The following workflow outlines the typical process for creating and validating a PDX model, as demonstrated in studies on breast and pediatric solid tumors [19] [22].

Key Experimental Steps [19] [22]:

- Sample Collection & Preparation: Fresh tumor specimens are obtained from patients with informed consent. The tissue is transported in storage solution on ice, rinsed, and minced into small fragments (∼3–4 mm) under sterile conditions.

- Implantation: Tumor fragments are surgically implanted into immunocompromised mice (e.g., NOD-SCID or NSG strains). Implantation can be orthotopic (e.g., mammary fat pad for breast cancer) or subcutaneous.

- Monitoring and Passaging: Mice are monitored for tumor engraftment and growth. Upon reaching a predefined volume (e.g., 1000-1500 mm³), the tumor is harvested. A portion is cryopreserved for biobanking, and other fragments are serially passaged into new mice to expand the model, creating subsequent generations (G1, G2, etc.).

- Validation: Critical steps to confirm model fidelity include:

- Histopathology (H&E staining): To confirm retention of the original tumor's histological architecture.

- Immunohistochemistry (IHC): To validate the expression of key biomarkers (e.g., ER, PR, HER2 for breast cancer).

- Short Tandem Repeat (STR) Profiling: A DNA fingerprinting technique to genetically match the PDX tumor to the patient's original sample. Concordance rates are typically high, reported at 81.1%–100% in recent studies [19] [22].

- RNA Sequencing / RT-PCR: To confirm the presence of driver genetic alterations, such as fusion genes, with high fidelity (e.g., 92.6% retention in sarcoma PDXs) [22].

Protocol for PDO Model Establishment

The establishment of PDOs, particularly for challenging cancers like renal cell carcinoma (RCC) and brain tumors, involves a distinct in vitro process [20] [18].

Key Experimental Steps [20] [18]:

- Tissue Processing: Patient tumor samples are processed rapidly to maintain viability. The tissue is dissociated mechanically and/or enzymatically to create a cell suspension or small cell clusters.

- 3D Culture: The dissociated cells are embedded in an extracellular matrix substitute (e.g., Matrigel, Geltrex), which provides a scaffold for 3D growth.

- Defined Culture Media: The embedded cells are cultured in a specialized, defined medium. The composition of this medium is critical and often needs to be optimized for specific cancer subtypes to support the growth of tumor cells while suppressing the outgrowth of normal cells. For example, RCC organoids may require specific growth factor combinations [18].

- Expansion and Maintenance: Organoids are allowed to grow and are periodically passaged by mechanically breaking them up and re-embedding the fragments into new matrix.

- Validation: Similar to PDX, PDOs are rigorously validated using:

- Histology and IHC: To demonstrate recapitulation of tumor morphology and protein marker expression.

- Genomic/Transcriptomic Analysis: Whole-exome sequencing, RNA sequencing, and single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) are used to confirm that organoids retain the molecular features, heterogeneity, and gene expression profiles of the parent tumor [20] [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The successful establishment and application of PDX and PDO models rely on a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The following table details key solutions used in the featured experiments.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for PDX and PDO Research

| Research Reagent | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Immunocompromised Mice (e.g., NOD-SCID, NSG) | In vivo hosts that allow engraftment and growth of human tumor tissue without immune rejection. | PDX Model Establishment [19] [22] |

| Extracellular Matrix (e.g., Matrigel, Geltrex) | Provides a 3D scaffold that supports cell polarization, self-organization, and survival of organoids. | PDO Model Establishment [20] [18] |

| Defined Culture Media & Growth Factors | A chemically defined cocktail of nutrients, hormones, and growth factors that selectively supports the growth of tumor epithelial cells. | PDO Model Establishment & Maintenance [18] |

| Short Tandem Repeat (STR) Profiling Kit | A molecular biology tool that amplifies specific genomic loci to create a DNA "fingerprint" for authenticating human origin and matching models to patient samples. | PDX & PDO Model Validation [19] [22] |

| EnVision FLEX Mini Kit (Dako) | A standardized immunohistochemistry (IHC) detection system used to visualize specific protein biomarkers (e.g., ER, HER2) in formalin-fixed tumor sections. | Histopathological Validation [19] |

Analysis of Histopathological and Genomic Retention

Performance Across Tumor Types

The success and fidelity of these models can vary significantly depending on the cancer type and subtype.

- PDX Engraftment Efficiency: A study establishing a pediatric solid tumor PDX biobank reported an overall success rate of 44.35% across 124 samples. Engraftment was notably higher for sarcomas (e.g., osteosarcoma, Ewing sarcoma) at >55%, while central nervous system (CNS) tumors had lower success rates, reflecting their unique microenvironmental requirements [22]. For treatment-resistant HR+/HER2- breast cancer, the median time for a palpable G0 PDX was 100 days, highlighting the slow growth of some subtypes [19].

- PDO Culture Success and Challenges: The establishment efficiency of PDOs is highly subtype-dependent. While protocols for cancers like colorectal and breast have been optimized, modeling renal cell carcinoma (RCC) presents specific hurdles. Clear cell RCC (ccRCC) organoids are more readily established, whereas papillary and particularly chromophobe RCC (chRCC) prove much more difficult due to molecular features that impair proliferative capacity and structural integrity in vitro [18].

Limitations and Drift

A critical consideration for both platforms is their potential deviation from the original tumor over time.

- Genetic Drift in PDX: While PDX models show high initial concordance, serial passaging can lead to changes. Second-generation PDX tumors often show faster growth, suggesting a selective adaptation to the murine host [22]. Sporadic discrepancies, such as the emergence of new fusion genes or the outgrowth of murine lymphoproliferative cells, have been observed, underscoring the necessity for ongoing molecular validation [19] [22].

- Phenotypic Instability in PDO: PDOs can experience "phenotypic drift" in long-term culture, where the cellular composition and molecular characteristics may gradually shift away from the original tumor. Furthermore, the absence of a native tumor microenvironment (TME)—including blood vessels, cancer-associated fibroblasts, and immune cells—remains a fundamental limitation for studying therapies that target these components, such as immunotherapies and anti-angiogenic drugs [17] [18]. Advanced co-culture systems are being developed to bridge this gap.

Overcoming the Limitations of Traditional 2D Cell Lines and CDX Models

For decades, cancer research has relied on traditional two-dimensional (2D) cell cultures and cell line-derived xenograft (CDX) models for drug discovery. However, their limited clinical predictive power has constrained progress. This guide compares two advanced, patient-derived models—Patient-Derived Xenografts (PDX) and Patient-Derived Organoids (PDO)—that are overcoming these limitations by better preserving the biological complexity of human tumors.

The table below provides a high-level comparison of the key characteristics of 2D, CDX, PDX, and PDO models to help researchers select the appropriate tool for their investigations [25] [26].

| Feature | Traditional 2D Cell Lines / CDX | Patient-Derived Xenografts (PDX) | Patient-Derived Organoids (PDO) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basis of Model | Immortalized, clonal cell lines [27] | Tumor tissue implanted directly into mice [1] | Tumor cells cultured as 3D structures in vitro [25] |

| Tumor Microenvironment | Poor; lacks stromal and immune components [1] | High; retains human stroma initially, replaced by mouse cells over time [1] | Moderate; can include some epithelial components, but lacks vascular and immune systems [17] |

| Intratumor Heterogeneity | Low (clonal) [28] | High (preserves patient tumor heterogeneity) [28] | Moderate to High (preserves cellular heterogeneity) [25] |

| Clinical Predictive Value | Low; high attrition rates in drug development [1] | High; demonstrated significant concordance with patient responses [17] [1] | High; performance similar to PDX in predicting patient response [17] |

| Throughput & Scalability | High (for 2D); Moderate (for CDX) | Low; time-consuming and resource-intensive [25] | High; amenable to high-throughput drug screening [17] [26] |

| Timeline & Cost | Low cost, rapid results | Long timeline (months), high cost [25] | Moderate timeline (weeks), lower cost than PDX [17] [25] |

| Key Advantages | Cost-effective, scalable, standardized | Retains in vivo biology and tumor architecture, gold standard for preclinical studies [1] | Cost-effective, high-throughput, retains patient-specific genetics, ethical advantages [17] |

| Primary Limitations | Genomically simplified, poor clinical translation [27] [1] | Low engraftment rates for some cancers, use of immunocompromised hosts, ethical concerns [25] | Lacks full tumor microenvironment, cannot model immune therapies or pharmacokinetics [17] |

Quantitative Predictive Performance Data

A systematic review and meta-analysis directly comparing the predictive accuracy of PDX and PDO models provides critical performance metrics. The analysis, which included 411 patient-model pairs (267 PDX, 144 PDO) from solid tumors, found that the overall concordance in treatment response between patients and matched models was 70%, with no significant differences in performance between PDX and PDO models [17].

The table below summarizes the detailed performance characteristics [17]:

| Metric | PDX Performance | PDO Performance | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Concordance | ~70% | ~70% | No statistically significant difference found between models [17]. |

| Sensitivity & Specificity | Comparable to PDO | Comparable to PDX | Values were comparable between the two model types [17]. |

| Positive Predictive Value (PPV) | Comparable to PDO | Comparable to PDX | PPV for organoid-informed treatment in colorectal cancer was 68% [29]. |

| Negative Predictive Value (NPV) | Comparable to PDO | Comparable to PDX | NPV for organoid-informed treatment in colorectal cancer was 78% [29]. |

| Association with Patient Survival | Significant | Significant | Patients whose matched PDOs responded to therapy had prolonged progression-free survival (PFS). For PDX, this association was strong in studies with low risk of bias [17]. |

Experimental Workflows and Protocols

PDX Model Establishment and Drug Trials

The following diagram illustrates the multi-generational process of establishing and utilizing PDX models for drug testing.

Key Methodological Steps for PDX Models [1]:

- Sample Acquisition and Implantation: Fresh tumor tissues from surgical resections or biopsies are collected and cut into small fragments (approx. 2-3 mm³). These fragments are implanted into immunocompromised mice (e.g., NOD-SCID, NSG) via subcutaneous, orthotopic, or renal capsule routes.

- Engraftment and Passage: Engrafted tumors are grown to a volume of 1-2 cm³, constituting the first generation (P0 or F1). The tumor is then harvested, divided, and re-implanted into new mice to create subsequent generations (P1, P2, etc.). The time for establishment varies from weeks to months.

- Characterization: PDX models must be validated to confirm they retain the histological architecture and molecular features (e.g., via DNA/RNA sequencing, IHC) of the original patient tumor.

- Drug Efficacy Studies: cohorts of mice bearing specific PDX models are treated with vehicle control or the investigational drug(s). Drug response is typically monitored by measuring tumor volume over time. A key advantage is the ability to create "Mouse Clinical Trials" or "Patient-Derived Clinical Trials" by testing a single drug across a large panel of different PDX models to mimic population-level response variability [1].

PDO Culture and High-Throughput Screening

The workflow for establishing and using PDOs for drug screening is outlined below.

Key Methodological Steps for PDO Models [25] [10]:

- Tissue Processing: Patient tumor samples are minced and digested with enzymes (e.g., collagenase) to create a single-cell suspension or small cell clusters.

- 3D Culture Setup: The cell suspension is mixed with a basement membrane extract (BME) like Matrigel, which provides a 3D scaffold. This mixture is plated and allowed to solidify.

- Defined Culture Medium: Organoids are cultured in a specialized, defined medium that varies by tumor type. Key additives often include:

- Growth Factors: EGF (Epidermal Growth Factor) to promote proliferation.

- Wnt Agonists: R-spondin to support stem cell function.

- BMP Inhibitors: Noggin to prevent differentiation.

- Other Pathway Modulators: such as A83-01 (a TGF-β inhibitor).

- Drug Screening: Expanded organoids are dissociated and re-plated in 384-well plates for high-throughput screening. After treatment with compound libraries, viability is measured using assays like ATP-based CellTiter-Glo. A sensitivity threshold (e.g., IC50) is applied to classify tumors as sensitive or resistant [29].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The table below details key reagents and their functions essential for establishing and maintaining PDX and PDO models.

| Reagent / Material | Function in PDX Models | Function in PDO Models |

|---|---|---|

| Immunocompromised Mice (e.g., NOD-SCID, NSG) | Essential in vivo host; prevents rejection of human tumor implant [1]. | Not Applicable |

| Basement Membrane Extract (BME/Matrigel) | Not typically used for initial implantation. | Critical 3D scaffold that provides structural support and mimics the extracellular matrix [25]. |

| R-spondin | Not a standard reagent. | Key growth factor in culture medium; agonist of Wnt signaling crucial for stem cell maintenance [10]. |

| Noggin | Not a standard reagent. | Key growth factor; inhibits BMP signaling to prevent differentiation of stem/progenitor cells [10]. |

| EGF (Epidermal Growth Factor) | Not a standard reagent. | Promotes cell proliferation and survival in the organoid culture medium [10]. |

| A83-01 (TGF-β Inhibitor) | Not a standard reagent. | Added to culture medium to inhibit TGF-β signaling, which can otherwise suppress growth and induce differentiation [25]. |

PDX and PDO models have moved beyond the limitations of traditional 2D and CDX systems, offering a more physiologically relevant and clinically predictive platform for oncology research. The choice between them is not a matter of which is universally better, but which is more appropriate for the specific research question.

- PDX models are the preferred choice for studying complex in vivo interactions, including tumor-stroma crosstalk, metastasis, and pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics (PK/PD), and for the final, most clinically relevant validation of therapeutic efficacy prior to human trials [1] [26].

- PDO models excel in applications requiring scale and speed, such as high-throughput drug screening, personalized medicine approaches, and genetic manipulation, offering a more ethical and cost-effective system [17] [30].

An integrated approach, using PDOs for large-scale initial screening followed by validation of top hits in PDX models, leverages the strengths of both platforms and represents a powerful strategy for accelerating the development of novel cancer therapeutics.

Patient-derived models have revolutionized cancer research by providing more physiologically relevant tools for studying tumor biology and treatment response. The two most prominent models in modern oncology are patient-derived xenografts (PDX), which involve transplanting human tumor tissue into immunocompromised mice, and patient-derived organoids (PDO), which are three-dimensional in vitro cultures derived from patient tumors [17] [11]. Both models have significantly advanced beyond traditional two-dimensional cell lines, which lack the structural architecture and cellular diversity of human tumors [31] [32]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of PDX and PDO models across the research spectrum, from fundamental biological investigation to clinical treatment personalization, empowering researchers to select the optimal model for their specific applications.

Model Foundations and Technical Specifications

Fundamental Characteristics and Working Principles

Patient-Derived Xenografts (PDX) are established by directly implanting fresh human tumor fragments into immunocompromised mouse hosts. These models maintain much of the original tumor's histological architecture and cellular heterogeneity while interacting with mouse stromal components [17]. PDX models require extensive use of animals, typically employing highly immunocompromised strains like NOD-SCID-IL2Rγnull (NSG) mice to improve engraftment rates [33]. The in vivo environment allows for preservation of some tumor-stroma interactions and provides a system for studying metastasis and systemic drug effects [7] [34].

Patient-Derived Organoids (PDO) are generated by embedding dissociated tumor cells in a basement membrane matrix and culturing them in specialized media containing growth factors and signaling pathway inhibitors [11] [8]. This approach recapitulates key architectural and molecular features of the original tumor in a three-dimensional in vitro system that can be rapidly expanded and maintained long-term [8]. However, PDO models typically lack the vascular and stromal complexity of in vivo systems, limiting their application for studying tumor-microenvironment interactions unless co-culture systems are implemented [17] [35].

Comparative Technical Specifications

Table 1: Technical comparison between PDX and PDO models

| Parameter | Patient-Derived Xenografts (PDX) | Patient-Derived Organoids (PDO) |

|---|---|---|

| Foundation | In vivo implantation in immunocompromised mice | 3D in vitro culture in extracellular matrix |

| Time to Establishment | 3-6 months | 2-8 weeks |

| Success Rates | Variable (10-80%) depending on cancer type | Generally higher across tumor types |

| Cost Considerations | High (animal maintenance, ethical costs) | Moderate (specialized media, matrices) |

| Scalability | Low to moderate | High (amenable to HTS) |

| Throughput | Low | High |

| Genetic Stability | Maintained over early passages | Generally high with defined protocols |

| Tumor Microenvironment | Partial (mouse stroma, human tumor) | Limited (can be enhanced with co-cultures) |

| Key Advantages | Preserves tumor architecture, in vivo context | Scalable, cost-effective, high clinical predictivity |

| Primary Limitations | Time-consuming, expensive, ethical considerations | Limited microenvironment, may miss systemic effects |

Predictive Performance and Validation

Concordance with Clinical Responses

Recent meta-analyses have systematically evaluated the predictive accuracy of both models. A comprehensive assessment of 411 patient-model pairs (267 PDX, 144 PDO) across solid tumors demonstrated 70% overall concordance in treatment response between patients and matched models, with no statistically significant differences between PDX and PDO models [17]. Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value were all comparable between the two platforms, suggesting similar capability for predicting both responsive and non-responsive clinical scenarios.

Evidence from specific cancer types reinforces these findings. In ovarian clear cell carcinoma, both PDX and PDO models accurately recapitulated the patient's clinical resistance to carboplatin, doxorubicin, and gemcitabine, while traditional 2D cell lines showed sensitivity to these same agents [11]. Similarly, in prostate cancer, PDX models and their derived organoids maintained transcriptomic and genomic similarity to primary tumors and demonstrated differential drug sensitivities that aligned with clinical expectations [34].

Survival Correlation and Clinical Relevance

The association between model responses and patient outcomes provides critical validation for both platforms. Patients whose matched PDOs responded to therapy showed significantly prolonged progression-free survival in clinical follow-up [17]. For PDX models, this association held true only when analyses were restricted to patient-model pairs with low risk of bias after rigorous quality assessment, highlighting the importance of methodological standardization in predictive modeling.

Table 2: Predictive performance metrics across cancer types

| Cancer Type | Model | Concordance with Patient Response | Key Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multiple Solid Tumors | PDX | 70% overall | Predictive accuracy similar between platforms | [17] |

| Multiple Solid Tumors | PDO | 70% overall | Association with patient PFS established | [17] |

| Ovarian Clear Cell | PDX | High | Recapitulated clinical resistance to carboplatin/doxorubicin/gemcitabine | [11] |

| Ovarian Clear Cell | PDO | High | Identified HDAC inhibitor belinostat as potentially effective | [11] |

| Prostate Cancer | PDX | High | Androgen-dependent responses mirrored clinical behavior | [34] |

| Gastric Cancer | Both | High | Models informed personalized treatment strategies | [33] |

Experimental Workflows and Methodologies

Model Establishment and Validation Protocols

PDX Establishment Protocol:

- Tumor Processing: Fresh tumor tissue is collected sterilely and cut into 3-5 mm³ fragments in cold preservation medium

- Implantation: Fragments are implanted subcutaneously (typically scapular region) or orthotopically into anesthetized immunocompromised mice

- Monitoring: Tumor growth is measured twice weekly until reaching 800-1000 mm³

- Passaging: Tumors are harvested, with portions used for analysis and serial transplantation into new mouse cohorts

- Validation: Histological comparison (H&E staining), genomic verification (DNA fingerprinting), and molecular characterization confirm fidelity to original tumor [11] [34]

PDO Establishment Protocol:

- Tissue Dissociation: Tumor tissue is dissociated using enzymatic kits (e.g., Tumor Dissociation Kit, Miltenyi Biotec) and mechanical disruption

- Matrix Embedding: Cells are resuspended in basement membrane extract (e.g., Matrigel) and plated as domes

- Specialized Media Culture: Cultures are maintained in organoid basal medium supplemented with niche factors (B27, N-acetylcysteine, EGF, FGF, ROCK inhibitor Y27632)

- Expansion: Organoids are passaged every 1-3 weeks through mechanical/ enzymatic dissociation and re-embedding

- Validation: Morphological assessment, lineage markers by immunofluorescence, and genomic profiling verify representation of original tumor [11] [8]

Drug Screening Methodologies

PDX Drug Testing Workflow:

- Cohort Design: Mice bearing passage 3-5 PDX tumors are randomized into treatment groups when tumors reach 150-200 mm³

- Dosing Regimen: Compounds are administered via clinically relevant routes (oral gavage, intraperitoneal injection) at mouse-equivalent doses of human treatments

- Response Monitoring: Tumor volumes and mouse weights are tracked 2-3 times weekly

- Endpoint Analysis: Tumors are harvested for molecular and histological analysis when control tumors reach endpoint volume [34] [33]

PDO Drug Screening Workflow:

- Platform Preparation: Organoids are dissociated into single cells or small clusters and seeded in 384-well plates

- Compound Exposure: Libraries of FDA-approved or investigational compounds are transferred via automated liquid handling

- Viability Assessment: Cell viability is quantified after 5-7 days using ATP-based, resazurin, or imaging-based assays

- Dose-Response Analysis: Multi-concentration testing generates IC₅₀ values and response classifications [11] [35]

Research Applications Across the Discovery-Clinical Spectrum

Basic Cancer Biology Applications

Both PDX and PDO models have become indispensable tools for investigating fundamental cancer processes. PDX models excel in studying tumor-stroma interactions, metastatic cascades, and systemic signaling due to their preserved tissue architecture and in vivo context [7] [34]. The mouse microenvironment, while not human, provides physiological cues that influence tumor behavior and evolution. Researchers have leveraged PDX models to map clonal evolution during treatment and identify microenvironment-driven resistance mechanisms.

PDO platforms offer distinct advantages for deconstructing tumor-intrinsic signaling pathways, mapping heterogeneity, and performing genetic screens [8]. The tractability of organoid systems enables precise manipulation of signaling pathways through media supplementation with growth factors and small molecule inhibitors. PDO biobanks representing molecularly annotated tumors have proven valuable for associating genetic alterations with phenotypic behaviors and identifying subtype-specific vulnerabilities.

Preclinical Drug Development Applications

In drug discovery, PDX models serve as the gold standard for in vivo efficacy assessment prior to clinical trials [7] [33]. Their conservation of tumor heterogeneity and pathophysiology provides critical insights into compound pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and therapeutic indices. PDX trials—where cohorts of models representing molecular subtypes are treated with investigational agents—help stratify patient populations most likely to respond and identify potential resistance mechanisms.

PDO systems enable unprecedented scalability in drug screening, with platforms routinely testing hundreds of compounds across large organoid panels [8] [35]. This high-throughput capacity is particularly valuable for combination therapy discovery, where testing thousands of drug pairs would be prohibitively expensive in vivo. PDO screens have successfully identified novel therapeutic candidates, including a bispecific antibody triggering EGFR degradation specifically in LGR5+ cancer stem cells, later validated in matched PDX models [35].

Functional Precision Medicine Applications

The most transformative application of both platforms lies in functional precision medicine, where models guide individual patient treatment decisions. Multiple studies have demonstrated that ex vivo drug sensitivity testing in PDOs can predict clinical response with high accuracy [11] [36]. The faster turnaround time of PDO screens (2-4 weeks versus 3-6 months for PDX) makes them more feasible for clinical decision support, particularly in advanced disease where treatment choices are time-sensitive.

PDX models still play important roles in addressing specific clinical questions, particularly for immunotherapies and complex microenvironment interactions not recapitulated in PDO cultures [33]. Humanized PDX models—where immunodeficient mice are engrafted with human immune systems—enable evaluation of checkpoint inhibitors and other immunomodulatory agents. For targeted therapies where microenvironment influence is less critical, PDOs provide a more scalable and cost-effective predictive tool.

Table 3: Application-specific recommendations and considerations

| Research Application | Recommended Model | Key Advantages | Important Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Targeted Therapy Screening | PDO | High-throughput capacity, genetic annotation | May miss paracrine signaling effects |

| Immunotherapy Assessment | Humanized PDX | Functional human immune system | Technically challenging, variable reconstitution |

| Metastasis Studies | PDX | Preserved invasion and colonization programs | Mouse stroma may not fully mimic human niche |

| Tumor Heterogeneity Analysis | Both | Maintain parental tumor diversity | Selection pressures may alter representation |

| Functional Precision Medicine | PDO (primary), PDX (validation) | Clinical turnaround (PDO), in vivo validation (PDX) | Establishment failure for some tumor types |

| Mechanistic Pathway Studies | PDO | Genetic manipulation, signaling dissection | Lack of systemic regulation |

| Co-clinical Trials | PDX | Parallel treatment with patients | Time and resource intensive |

Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful implementation of PDX and PDO platforms requires specialized reagents and materials. The following table details key solutions used in model establishment and maintenance.

Table 4: Essential research reagents and solutions for PDX and PDO workflows

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Model Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Immunocompromised Mice | NOD-scid-IL2Rγnull (NSG), NOG | Host organisms for PDX engraftment | PDX |

| Basement Membrane Matrix | Matrigel, BME-2 | 3D scaffold for organoid growth | PDO |

| Dissociation Reagents | Tumor Dissociation Kit (Miltenyi), collagenase | Tissue processing into single cells | Both |

| Specialized Media Supplements | B27, N-acetylcysteine, nicotinamide | Support stem cell maintenance | PDO |

| Growth Factors | EGF, FGF-10, FGF-basic, Noggin | Mimic niche signaling pathways | PDO |

| Signaling Inhibitors | A-83-01 (TGF-β inhibitor), Y27632 (ROCK inhibitor) | Prevent differentiation and apoptosis | PDO |

| Validation Reagents | Species-specific antibodies, PCR panels | Confirm human origin and contamination | Both |

| Cryopreservation Media | DMSO/FBS solutions | Long-term model biobanking | Both |

Integrated Workflows and Future Directions

The complementary strengths of PDX and PDO models have inspired integrated workflows that leverage both platforms throughout the drug discovery pipeline. A common strategy employs PDO screens for high-throughput compound identification followed by PDX models for in vivo validation of prioritized hits [35]. This approach balances efficiency with physiological relevance, accelerating the development of promising therapeutic candidates.

Emerging technologies are addressing current limitations of both platforms. For PDO models, microfluidic organ-on-chip systems and co-culture methods are incorporating immune cells, fibroblasts, and endothelial cells to better mimic tumor microenvironment complexities [8] [36]. For PDX models, humanized mouse strains with improved human immune system reconstitution are enabling more accurate evaluation of immunotherapies [33]. Both model systems are increasingly being paired with computational approaches, including machine learning algorithms that predict drug response based on molecular features combined with functional data.

The evolution of these platforms continues to enhance their translational impact. As biobanks expand to encompass broader tumor diversity and protocols standardize across laboratories, PDX and PDO models will play increasingly central roles in bridging basic cancer biology with personalized clinical care, ultimately improving outcomes for cancer patients through more precise and effective therapeutic strategies.

Practical Implementation: Establishment Protocols and Translational Applications in Drug Discovery

In the evolving landscape of precision oncology, patient-derived xenograft (PDX) and patient-derived organoid (PDO) models have emerged as indispensable "patient avatar" systems for preclinical research and therapeutic prediction. These models represent a paradigm shift from genomics-based medicine toward functional precision medicine, which evaluates therapeutic efficacy by directly treating living patient tumors ex vivo to better predict patient-specific responses [36]. While both model types aim to bridge the gap between traditional preclinical models and human clinical response, they offer distinct advantages and limitations in terms of predictive accuracy, establishment complexity, cost, and ethical considerations [17] [26].

A recent comprehensive meta-analysis comparing these avatar systems revealed no significant difference in overall predictive performance, with both models demonstrating approximately 70% concordance with patient treatment responses [17]. This comparative guide provides an objective, data-driven analysis of PDX and PDO model establishment, from initial tissue acquisition through functional assay implementation, empowering researchers to select the most appropriate model system for their specific research applications.

Model Establishment: Comparative Workflows

Tissue Acquisition and Sample Preparation

The initial phase of model establishment requires careful consideration of sample source and preparation techniques, which vary significantly between PDX and PDO approaches.

PDX Models typically utilize surgically resected tumor fragments, preferably within 2 hours of resection to maintain tissue viability [36]. Both primary and metastatic tumor sites can serve as source material, with the transplantation success rate heavily influenced by tumor type and grade [7] [36].

PDO Models offer more diverse sampling options, including:

- Surgical specimens from endoscopic biopsies or resection specimens [14]

- Minimally invasive sources such as pleural effusions, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, ascites, urine, and peripheral blood [14]

- Existing models including PDX tissues or established cell lines [14]

The preparation of PDO samples involves meticulous mechanical disruption using scalpels, followed by enzymatic digestion with collagenase/hyaluronidase and TrypLE Express enzymes appropriate for the specific tumor type [14]. For digestions exceeding 2 hours, adding a ROCK inhibitor (10 µM) improves growth efficiency by enhancing cell survival [14].

Table: Sample Acquisition and Preparation Requirements

| Parameter | PDX Models | PDO Models |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Sample Sources | Surgical resection fragments [36] | Surgical specimens, body fluids, existing models [14] |

| Time to Processing | <2 hours preferred [36] | 4 hours from sample to culture [37] |

| Preparation Methods | Minced tissue fragments [36] | Mechanical chopping, enzymatic digestion [14] [37] |

| Critical Reagents | Storage media for transport [36] | Collagenase/hyaluronidase, TrypLE Express, ROCK inhibitor [14] |

| Sample Volume Requirements | Millimeter-scale tissue fragments [36] | Small biopsies (1-3 mm³) or milliliter-scale fluids [14] [37] |

Core Establishment Protocols

The fundamental divergence in model establishment occurs after sample preparation, with PDX models requiring in vivo engraftment and PDO models utilizing three-dimensional in vitro culture systems.

PDX Establishment Protocol

The establishment of PDX models involves implanting prepared tumor tissue into immunocompromised mice, which can be achieved through several methodological approaches:

- Host Selection: Immunocompromised mice (e.g., NSG, nude strains) serve as hosts to prevent graft rejection [7].

- Implantation Methods:

- Monitoring and Passaging: Tumor growth is monitored regularly, with successful engraftments serially passaged to expand model numbers [38].

The successful construction rate of PDX models varies significantly by cancer type and is influenced by factors such as tumor grade, aggressiveness, and stromal content [7] [36].

PDO Establishment Protocol

The establishment of PDO models centers on creating a supportive three-dimensional environment that promotes stem cell maintenance and self-organization:

- Extracellular Matrix (ECM) Embedding: The digested cell pellets or tissue fragments are resuspended in a gelatinous protein mixture such as Matrigel, BME, or Geltrex [14] [37]. These hydrogels provide crucial growth factors and structural support for three-dimensional development.

- Plating Technique: The cell-ECM mixture is plated as small drops (10-20 μL) onto multi-well plates, typically using 98-, 48-, or 24-well formats [14]. The plates are inverted during incubation at 37°C for 15-30 minutes to prevent cell settling and promote hemispherical 3D structure formation.

- Culture Initiation: After ECM solidification, organoid-specific culture medium is added, and plates are maintained at 37°C with 5% CO₂ [37]. The liquid feed is renewed every few days, with organoids typically developing within approximately 2 weeks [37].

The PDO establishment process from tissue receipt to culture incubation takes approximately 4 hours of active processing time [37].

Model Expansion and Maintenance

Long-term model propagation requires specialized techniques for both PDX and PDO systems.

PDX Maintenance relies on serial passaging in mice, where established tumors are harvested and re-implanted into new host animals. The Mayo Clinic Brain Tumor PDX National Resource and similar facilities provide standardized protocols for these processes, including in vitro culture techniques for specific PDX lines [38].

PDO Expansion utilizes a subculture process called "passaging":

- Matrix Dissolution: The Matrigel surrounding organoids is dissolved using specific buffers [37].

- Organoid Dissociation: Organoids are broken apart either mechanically (pipetting through narrow openings) or chemically using enzyme solutions [37].

- Re-plating: The resulting cell clusters are centrifuged, resuspended in fresh Matrigel, and cultured as in the initial establishment [37].

This passaging process can be repeated multiple times, generating substantial material for research applications. For large-scale needs, semi-automated bioprocess technology has been developed to produce standardized PDOs with reduced batch-to-batch variability [37].

Functional Assays and Predictive Value Assessment

Drug Treatment and Response Assessment

The ultimate validation of both PDX and PDO models lies in their ability to accurately predict patient responses to therapeutic agents.

Treatment Protocol Design requires careful attention to dosing strategies. For PDX models, when multiple doses are tested, the closest murine equivalent of the clinical dose should be selected using established conversion methods [17]. For both models, the route of administration should mirror the clinical approach whenever possible [17].

Response Assessment methodologies differ between models:

- PDX Response: Typically measured by tumor volume reduction in vivo, often using caliper measurements or imaging [17]

- PDO Response: Assessed through viability assays (e.g., CellTiter-Glo), morphology changes, or functional readouts in vitro [8]

The meta-analysis of 411 patient-model pairs demonstrated that patients whose matched PDOs responded to therapy had significantly prolonged progression-free survival [17]. For PDX models, this association was statistically significant only when analyses were restricted to patient-model pairs with low risk of bias [17].

Predictive Performance Metrics

The comprehensive meta-analysis of 267 PDX and 144 PDO pairs from solid tumors treated with identical anti-cancer agents as matched patients provides robust comparative data on model predictive performance [17].

Table: Predictive Performance Metrics from Meta-Analysis

| Performance Metric | PDX Models | PDO Models | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Concordance | 70% | 70% | Not significant [17] |

| Sensitivity | Comparable | Comparable | Not significant [17] |

| Specificity | Comparable | Comparable | Not significant [17] |

| Positive Predictive Value | Comparable | Comparable | Not significant [17] |

| Negative Predictive Value | Comparable | Comparable | Not significant [17] |

| Association with Patient PFS | Significant only in low-bias pairs [17] | Significant association [17] | - |

Technical Considerations and Quality Control

Quality Assessment and Validation

Robust quality control measures are essential for ensuring model fidelity and predictive reliability. A standardized risk of bias assessment tool adapted from the Newcastle-Ottawa scale has been developed for this purpose, encompassing six key criteria [17]:

- Selection Bias Assessment: Evaluation of whether the paper included treatment responses from all PDX or PDO-matched patient pairs from the modeling project

- Origin Validation: Verification that models were successfully validated to originate from matching human tissue through DNA, RNA, protein-based assays, or histology

- Outcome Objectivity: Determination of whether patient response was assessed using RECIST criteria and model response data was obtained objectively

- Follow-up Adequacy: Assessment of whether patient follow-up was sufficiently long for meaningful survival evaluation (≥6 months or until earlier death)

- Reporting Sufficiency: Evaluation of comprehensive reporting including matching administration routes, dosing regimens, and previous treatment lines

- Technical Replicates: Verification that at least n=3 replicates were used for PDX or PDO experiments

Patient-model pairs meeting ≥4 of these criteria are classified as high reliability (low risk of bias), while those meeting ≤3 criteria are considered low reliability (high risk of bias) [17].

The Research Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful model establishment and maintenance require specific, specialized reagents and materials that constitute the essential research toolkit for both PDX and PDO workflows.

Table: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Model Establishment

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application |

|---|---|---|

| Matrigel/BME/Geltrex | Extracellular matrix hydrogel providing structural support and growth factors for 3D development [14] [37] | PDO Establishment |

| Collagenase/Hyaluronidase | Enzyme cocktail for tissue digestion and cell cluster isolation [14] | PDO Sample Preparation |

| TrypLE Express | Enzyme solution for further dissociation of cell clusters [14] | PDO Sample Preparation |

| ROCK Inhibitor (Y-27632) | Enhances cell survival during digestion and early culture stages [14] | PDO Establishment |

| Organoid Culture Media | Specialized media containing nutrients and growth factors (e.g., R-spondins, Noggin) [39] | PDO Maintenance |

| Immunocompromised Mice | Host organisms for PDX engraftment and propagation [7] | PDX Establishment |

| Cryopreservation Media | Specialized solutions for long-term model storage and biobanking [14] | Both Models |

The establishment of PDX and PDO models from tissue acquisition through functional assays represents a sophisticated technological pipeline for advancing precision oncology. The comparative analysis reveals that both models demonstrate equivalent predictive accuracy for treatment response, with approximately 70% concordance with patient outcomes [17].

The selection between PDX and PDO models should be guided by specific research requirements:

- PDX models offer a more physiologically relevant microenvironment and are preferred for studying complex tumor-stroma interactions, angiogenesis, and therapies requiring an intact immune system (though limited to murine immunity) [26].

- PDO models excel in high-throughput drug screening applications due to faster establishment timelines, lower costs, reduced ethical complexity, and superior scalability [17] [26] [8].

For comprehensive precision oncology programs, these models can serve complementary roles—with PDOs enabling rapid initial drug screening and PDXs providing validated in vivo confirmation of promising therapeutic candidates. This integrated approach maximizes both efficiency and clinical relevance in the development of personalized cancer treatments.

In the pursuit of effective cancer therapeutics, researchers rely on preclinical models that faithfully recapitulate human tumor biology. For decades, the field has been divided between traditional two-dimensional (2D) cell lines, which offer high-throughput capability but low clinical relevance, and patient-derived xenograft (PDX) models, which provide high clinical fidelity but are resource-intensive and low-throughput [40]. This dichotomy has created a significant gap in the drug discovery pipeline, necessitating a model that combines the scalability of in vitro systems with the predictive power of in vivo models. Enter patient-derived xenograft-derived organoids (PDXOs)—a hybrid technology that is rapidly bridging this critical divide. PDXOs are three-dimensional (3D) in vitro models generated from patient-derived xenografts, effectively combining the strengths of both parent platforms [35] [41]. This comparative analysis examines the predictive value of PDXOs against established PDX and patient-derived organoid (PDO) models, providing researchers with a scientific framework for model selection in preclinical oncology research.

Model Fundamentals: PDX, PDO, and the Emergence of PDXO

Defining the Core Preclinical Platforms

Patient-Derived Xenografts (PDXs) are established by directly implanting fragments of patient tumor tissue into immunodeficient mice. These models are considered the gold standard for in vivo preclinical research because they maintain key features of the original tumor, including its 3D architecture, genetic profile, and heterogeneity [42] [7]. PDXs are particularly valued for their ability to preserve the stromal component and tumor microenvironment (TME) during early passages, though this human stroma is gradually replaced by mouse cells over time [42] [43]. Their primary applications include late-stage drug validation, biomarker discovery, and co-clinical trials [42].

Patient-Derived Organoids (PDOs) are 3D in vitro structures grown from patient tumor stem cells using specialized matrices and cytokine protocols. First pioneered for intestinal tissue by Sato et al. in 2009, organoid technology enables long-term expansion while preserving the genetic and phenotypic characteristics of the original tumor [40] [44]. PDOs excel in high-throughput drug screening and genetic manipulation but often lack the complete tumor microenvironment, particularly native immune and stromal cells [35] [40].