Prognostic vs Predictive Biomarkers: A Comprehensive Framework for Clinical Utility Assessment in Drug Development

This article provides a systematic guide for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on evaluating the clinical utility of prognostic and predictive biomarkers.

Prognostic vs Predictive Biomarkers: A Comprehensive Framework for Clinical Utility Assessment in Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a systematic guide for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on evaluating the clinical utility of prognostic and predictive biomarkers. It covers foundational definitions, methodological approaches for development and application, strategies to overcome common implementation challenges, and robust validation frameworks. By integrating insights from recent advances in multi-omics, artificial intelligence, and clinical trial design, this review offers actionable methodologies to bridge the gap between biomarker discovery and clinical implementation, ultimately supporting more efficient and personalized therapeutic development.

Demystifying Biomarker Fundamentals: From Core Definitions to Clinical Context

In the era of personalized medicine, biomarkers have become indispensable tools for refining diagnosis, prognostication, and treatment selection. A clear understanding of the distinct roles played by different classes of biomarkers is fundamental to their correct application in both drug development and clinical practice. Two categories, prognostic and predictive biomarkers, are particularly crucial, yet their concepts are frequently conflated. A prognostic biomarker is defined as "a biomarker used to identify likelihood of a clinical event, disease recurrence or progression in patients who have the disease or medical condition of interest" [1]. In essence, it provides information about the natural history of the disease, independent of any specific therapy. In contrast, a predictive biomarker is "used to identify individuals who are more likely than similar individuals without the biomarker to experience a favorable or unfavorable effect from exposure to a medical product or an environmental agent" [2]. It informs on the likelihood of response to a specific therapeutic intervention.

The clinical utility of a biomarker—the extent to which it improves patient outcomes and healthcare decision-making—is the ultimate measure of its value [3] [4]. This guide provides a detailed, objective comparison of prognostic and predictive biomarkers, underpinned by foundational definitions, experimental data, and methodological protocols, to serve researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Core Conceptual Differences and Direct Comparison

The fundamental distinction lies in the clinical question each biomarker type answers. A prognostic biomarker addresses "What is the likely course of my patient's disease?", while a predictive biomarker addresses "Will this specific treatment work for my patient?" [5]. This difference dictates their application; prognostic markers are used for patient stratification and counseling about disease outcomes, whereas predictive markers are used for treatment selection [6] [2].

Table 1: Core Conceptual Comparison of Prognostic and Predictive Biomarkers

| Feature | Prognostic Biomarker | Predictive Biomarker |

|---|---|---|

| Core Question | What is the likely disease outcome? | Will this specific treatment be effective? |

| Clinical Utility | Stratifies patients by risk of future events (e.g., recurrence, death) [1]. | Identifies patients most likely to benefit from a specific therapy [2]. |

| Effect of Biomarker | The association between the biomarker and outcome is present without reference to different interventions [1]. | Acts as an effect modifier; the biomarker status changes the effect of the therapy [6] [2]. |

| Interpretation Context | Interpretation is relative to the natural history of the disease or a standard background therapy. | Interpretation is always relative to a specific therapeutic intervention and a control. |

| Typical Study Design for Validation | Often identified from observational data in a defined patient cohort [1]. | Generally requires a comparison of treatment to control in patients with and without the biomarker, ideally from randomized trials [6] [2]. |

Illustrative Examples in Oncology

The following examples, summarized in the table below, clarify these concepts in a concrete context.

Table 2: Exemplary Biomarkers in Oncology

| Biomarker | Type | Clinical Context | Utility and Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chromosome 17p deletion / TP53 mutation [1] | Prognostic | Chronic Lymphocytic Leukaemia (CLL) | Assesses likelihood of death, indicating a more aggressive disease course. |

| Gleason Score [1] | Prognostic | Prostate Cancer | Assesses likelihood of cancer progression based on tumor differentiation. |

| BRCA1/2 mutations | Dual | Breast Cancer | Prognostic: Evaluates likelihood of a second breast cancer [1].Predictive: Identifies likely responders to PARP inhibitors in platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer [2]. |

| HER2/neu amplification [7] [5] | Predictive | Breast Cancer | Identifies patients who are likely to respond to HER2-targeted therapies like Trastuzumab. |

| EGFR mutations [5] | Predictive | Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) | Identifies patients likely to respond to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors. |

| BRAF V600E mutation [6] | Predictive | Melanoma | Identifies patients with late-stage melanoma who are candidates for BRAF inhibitor therapy (e.g., vemurafenib). |

Methodological Frameworks for Biomarker Assessment

Experimental Design for Distinguishing Prognostic from Predictive Effects

A common point of confusion arises because a biomarker can be both prognostic and predictive. Isolating a purely predictive effect requires a specific study design that includes a control group not receiving the investigational therapy. As the FDA-NIH Biomarker Working Group explains, demonstrating that biomarker-positive patients have a better outcome on an experimental therapy does not, by itself, establish a predictive effect. The same survival difference could be due to the biomarker's prognostic ability [6]. A predictive effect is established by a significant treatment-by-biomarker interaction, where the difference in outcome between the experimental and control therapies is greater in the biomarker-positive group than in the biomarker-negative group [6] [2].

Phased Approach for Evaluating Clinical Utility

Establishing that a biomarker is statistically associated with an outcome is only the first step. Proving its clinical utility—that its use actually improves patient management and health outcomes—requires a phased approach [3] [8]. These phases progress from early discovery to confirmation of real-world effectiveness.

Table 3: Phases of Biomarker Development and Assessment

| Phase | Primary Objective | Key Methodological Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Discovery [8] | To identify a biomarker associated with pathology or a biological process. | Focus on biological plausibility and initial measurement reliability. Often uses "predictor-finding" studies. |

| 2. Translation [8] | To determine if the biomarker can separate diseased from non-diseased, or high-risk from low-risk patients. | Evaluation of diagnostic accuracy (sensitivity, specificity, AUC). Requires a clear reference standard. |

| 3. Single-Center Clinical Utility [8] | To assess if the biomarker is useful in clinical practice at a single site. | Evaluation of impact on clinical decision-making and patient outcomes (e.g., via biomarker-strategy RCTs [3]). |

| 4. Multi-Center Validation & Cost-Effectiveness [8] | To confirm utility across multiple centers and assess economic impact. | Large-scale studies to ensure generalizability. Formal cost-effectiveness analysis is conducted [4]. |

Determining Clinical Utility and Cut-Points

The gold standard for measuring the health impact of a biomarker strategy is a randomized controlled trial where participants are randomized to a management strategy that uses the biomarker result versus one that does not [3]. This design directly measures whether biomarker-informed care leads to better outcomes, such as reduced hospitalizations or improved quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) [3].

Furthermore, selecting the optimal cut-point for a continuous biomarker can be guided by clinical utility rather than just statistical accuracy. Methods are being developed that incorporate the clinical consequences of test results, integrating diagnostic accuracy (sensitivity, specificity) with the outcomes of clinical decisions (e.g., maximizing total clinical utility or balancing positive and negative utility) [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The transition of a biomarker from a research concept to a validated diagnostic, especially a companion diagnostic, demands rigorous standardization of reagents and protocols [7].

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Biomarker Development

| Reagent/Material | Function in Biomarker Assay Development | Critical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Validated Primary Antibodies (for IHC) [7] | Specifically binds to the target protein analyte in tissue sections. | Requires extensive validation for specificity and sensitivity in the specific assay platform (e.g., FFPE tissues). Changes in antibody lot or vendor may require re-validation. |

| Cell Line Controls [7] | Serves as a reference standard for assay performance and reproducibility across runs. | Must be prepared to give consistent protein expression levels. Ideally, multiple controls spanning the assay's dynamic range (e.g., negative, low-positive, high-positive) are used. |

| Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded (FFPE) Tissue | The standard substrate for retrospective and diagnostic tissue-based biomarker studies. | Pre-analytical variables (cold ischemia time, fixation duration, processing) significantly impact results, especially for phospho-proteins and labile biomarkers [7]. |

| Automated Staining Platforms | Performs the immunoassay (IHC) under tightly controlled, reproducible conditions. | Automation minimizes protocol "tweaking" and operator-to-operator variability, which is critical for quantitative or semi-quantitative assays [7]. |

| Digital Whole Slide Imaging (WSI) & Analysis Software | Enables quantitative, objective analysis of biomarker expression (e.g., H-score, percentage of positive cells). | Moves interpretation beyond subjective "eyeballing." Algorithms must be validated against clinical outcomes to ensure their scoring is clinically relevant [7]. |

The precise distinction between prognostic and predictive biomarkers is not merely academic; it is a foundational prerequisite for their valid development and application in clinical trials and patient care. Prognostic biomarkers illuminate the disease trajectory, while predictive biomarkers guide the therapeutic journey. The future of biomarker development lies in robust methodological frameworks that progress from discovery to the unequivocal demonstration of clinical utility through well-designed trials. As the field advances towards increasingly personalized medicine, the rigorous standards exemplified by companion diagnostics—treating assays as precise quantitative tools rather than qualitative stains—will become the benchmark for all biomarker development [7].

In the evolving landscape of precision medicine, the precise differentiation between outcome indicators and treatment response predictors represents a fundamental requirement for effective drug development and clinical trial design. These distinct categories of biomarkers serve different purposes, require different validation approaches, and inform different clinical decisions. Outcome indicators, more formally known as prognostic biomarkers, provide information about a patient's overall disease course, including natural progression and long-term outcomes, regardless of specific therapeutic interventions. In contrast, treatment response predictors, or predictive biomarkers, identify patients who are more likely to respond favorably to a particular treatment, enabling therapy selection tailored to individual biological characteristics [10].

The clinical utility of this distinction extends beyond academic classification to practical implementation across therapeutic areas. In oncology, for example, biomarkers guide therapy selection for numerous cancer types, while in psychiatry, they are increasingly employed to optimize antidepressant selection. The critical importance of this differentiation lies in its direct impact on clinical decision-making, clinical trial optimization, drug development efficiency, and ultimately, patient outcomes. Misclassification or conflation of these biomarker types can lead to flawed trial designs, inappropriate treatment decisions, and failed drug development programs. This guide provides a structured comparison of these biomarker categories, supported by experimental data and methodological details to inform researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Comparative Analysis: Prognostic versus Predictive Biomarkers

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Prognostic and Predictive Biomarkers

| Characteristic | Prognostic Biomarkers | Predictive Biomarkers |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Function | Provide information about disease course and long-term outcomes | Identify likelihood of response to specific treatments |

| Clinical Utility | Stratify patients by disease aggressiveness, inform monitoring intensity | Guide therapy selection, optimize treatment benefit-risk ratio |

| Measurement Timing | Often measured at baseline or diagnosis | Typically assessed pretreatment |

| Decision Impact | Informs "what will happen" to the patient | Informs "which treatment will work" |

| Representative Examples | S100B in melanoma, LDH in multiple cancers [10] | PD-L1 in NSCLC, MSI-H/dMMR status in colorectal cancer [10] |

Table 2: Clinical Application and Evidence Requirements

| Parameter | Prognostic Biomarkers | Predictive Biomarkers |

|---|---|---|

| Evidence Standard | Association with outcomes across treatment types | Specific interaction with particular therapeutic intervention |

| Trial Design | Often evaluated in observational studies or untreated arms | Require randomized controlled trials with treatment interaction analysis |

| Validation Approach | Consistent association with disease outcomes across populations | Demonstrated differential treatment effect between biomarker-positive and negative groups |

| Regulatory Consideration | May inform patient stratification or subgroup identification | Often required for companion diagnostic approval |

Methodological Approaches: Experimental Protocols for Biomarker Validation

Neuroimaging Biomarkers for Antidepressant Response Prediction

Recent research has established protocols for developing neuroimaging-based predictive biomarkers for antidepressant treatment response, with demonstrated cross-trial generalizability. In a prognostic study examining major depressive disorder (MDD) outcomes, researchers implemented a standardized methodology across two large multisite studies [11].

Experimental Protocol:

- Study Design: Prognostic study using data from EMBARC (US) and CANBIND-1 (Canadian) randomized clinical trials

- Participants: 363 adult MDD patients (225 from EMBARC, 138 from CANBIND-1; mean age 36.6±13.1 years; 64.7% female)

- Interventions: Sertraline (EMBARC) and escitalopram (CANBIND-1) administration

- Data Collection: Structural and functional resting-state MRI at baseline, clinical and demographic data, depression severity scores at baseline and week 2

- Predictor Variables: Clinical features (age, sex, employment, baseline depression severity, anhedonia scores, BMI) and neuroimaging features (functional connectivity of dorsal anterior cingulate cortex [dACC] and rostral anterior cingulate cortex [rACC])

- Outcome Measures: Treatment response defined as ≥50% reduction in depression severity at 8 weeks

- Analytical Approach: Elastic net logistic regressions with regularization; performance assessed using balanced classification accuracy and area under the curve (AUC)

- Validation Method: Cross-trial generalizability testing (training on one trial, testing on the other)

Key Findings: The best-performing models combining clinical features and dACC functional connectivity demonstrated substantial cross-trial generalizability (AUC = 0.62-0.67). The addition of neuroimaging features significantly improved prediction performance compared to clinical features alone. Early-treatment (week 2) depression severity scores provided the best generalization performance, comparable to within-trial performance [11].

Machine Learning Framework for Treatment Selection in Depression

The AID-ME study developed an artificial intelligence model to personalize treatment selection in major depressive disorder, representing an advanced approach to predictive biomarker implementation [12].

Experimental Protocol:

- Data Source: 22 clinical trials with 9042 adults with moderate to severe MDD

- Predictor Variables: Clinical and demographic variables routinely collectible in practice

- Outcome Measure: Remission across multiple pharmacological treatments

- Model Architecture: Deep learning model predicting probabilities of remission for 10 treatments

- Validation Approach: Held-out test-set validation, hypothetical and actual improvement testing, bias assessment

- Performance Metrics: AUC, population remission rate improvement, drug ranking variation

Key Findings: The model demonstrated an AUC of 0.65 on the held-out test-set, significantly outperforming a null model. It increased population remission rate in testing and showed significant variation in drug rankings across patient profiles without amplifying harmful biases [12].

Multi-Omics Biomarker Development in Prostate Cancer

A comprehensive approach to biomarker development in prostate cancer illustrates the integration of prognostic and predictive elements through multi-omics analysis [13].

Experimental Protocol:

- Data Sources: TCGA-PRAD bulk RNA sequencing datasets, single-cell RNA sequencing data (GSE206962), clinical cohorts from DKFZ and GEO repositories

- Analytical Methods: FindAllMarkers, Dseq2 R package, ssGSEA, WGCNA at single-cell and bulk transcriptome scales

- Machine Learning Framework: 14 algorithms with 162 algorithmic combinations to develop consensus immune and prognostic-related signatures (IPRS)

- Validation Approach: Systematic validation in training and test cohorts, multivariate nomogram construction

- Additional Assessments: Multi-omics analyses (genomic, single-cell transcriptomic, bulk transcriptomic), immunotherapy response evaluation, drug selection relevance

Key Findings: Identification of 91 genes associated with prognosis in the tumor microenvironment, with 15 connected to biochemical recurrence. The consensus IPRS demonstrated potential value in prognosis prediction and clinical relevance, with significant differences in biological functions, immune infiltration, and genomic mutations observed among different risk groups [13].

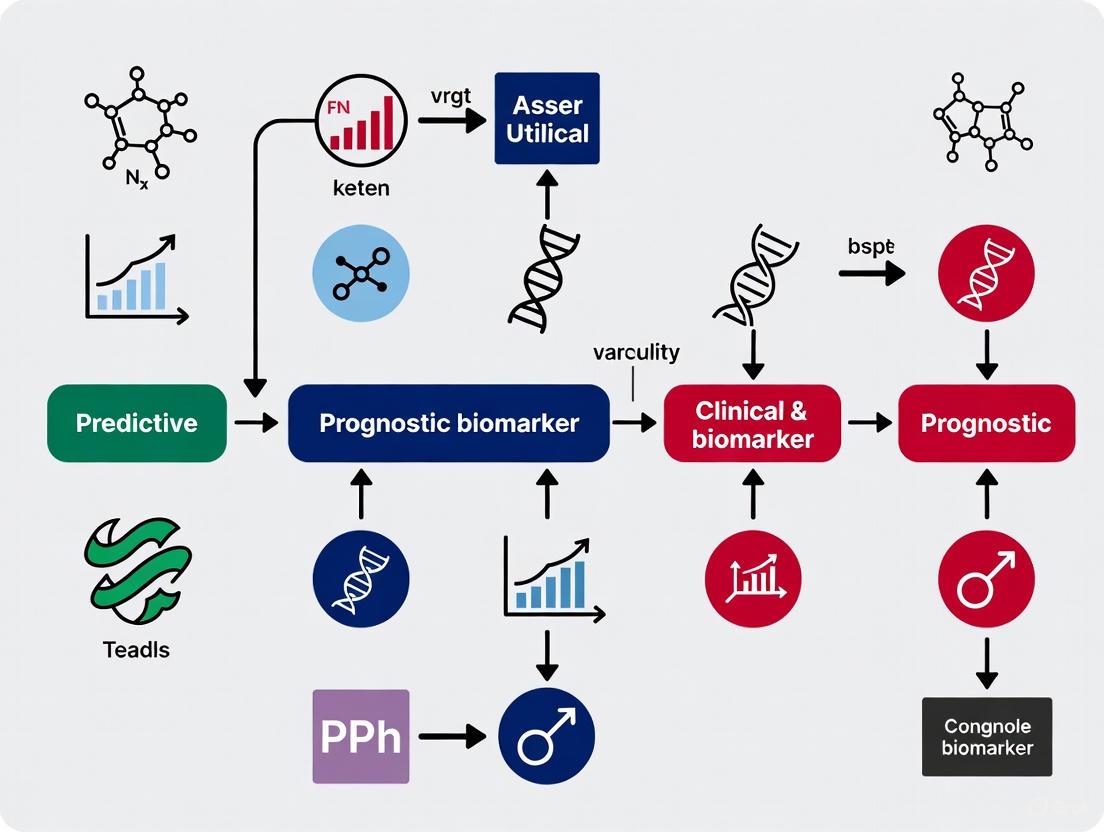

Visualizing Biomarker Pathways and Relationships

Biomarker Clinical Application Pathways

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Biomarker Research

| Tool/Platform | Primary Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| fMRIPrep | Standardized functional MRI data preprocessing | Neuroimaging biomarker development for antidepressant response prediction [11] |

| Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA) | Identification of gene co-expression patterns | Prostate cancer prognostic signature development [13] |

| Single-cell RNA sequencing | Resolution of cellular heterogeneity within tumor microenvironment | Characterization of prostate cancer tumor microenvironment [13] |

| Liquid biopsy platforms | Non-invasive detection of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) | Early cancer detection, monitoring treatment response [14] [15] |

| Elastic net regularization | Variable selection and regularization in predictive modeling | Prediction of antidepressant treatment response [11] |

| Deep learning architectures | Complex pattern recognition across multiple treatments | Differential treatment benefit prediction for depression [12] |

| Next-generation sequencing (NGS) | Comprehensive genomic profiling | Mutation detection, fusion identification, copy number alteration analysis [14] |

| Multi-omics integration platforms | Combined analysis of genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic data | Improved biomarker precision for immunotherapy response [10] |

Clinical Implementation and Validation Frameworks

The translation of biomarkers from research discoveries to clinically applicable tools requires rigorous validation frameworks. For predictive biomarkers, this typically involves demonstration of a significant treatment-by-biomarker interaction in randomized controlled trials. The example of PD-L1 as a predictive biomarker for immunotherapy response in non-small cell lung cancer illustrates this validation process, where the KEYNOTE-024 trial showed that patients with PD-L1 expression ≥50% experienced significantly improved outcomes with pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy (median overall survival: 30.0 months vs. 14.2 months; HR: 0.63; 95% CI: 0.47-0.86) [10].

For prognostic biomarkers, validation requires consistent association with clinical outcomes across multiple patient populations and study designs. The incorporation of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) into the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging for melanoma exemplifies this process, where elevated LDH levels consistently demonstrate association with poor prognosis across multiple studies [10]. The emerging field of multi-omics biomarkers represents a promising approach to overcoming the limitations of single-analyte biomarkers, with studies demonstrating approximately 15% improvement in predictive accuracy when integrating genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic data through machine learning models [10].

The critical distinction between outcome indicators and treatment response predictors carries significant implications for drug development strategy and clinical trial design. Prognostic biomarkers enable enrichment of trials with patients at higher risk of disease progression, potentially reducing sample size requirements and study duration for outcomes-driven trials. Predictive biomarkers facilitate targeted drug development by identifying patient subgroups most likely to benefit from specific therapeutic interventions, potentially increasing trial success rates and supporting personalized medicine approaches. As biomarker science continues to evolve, the integration of multi-omics approaches, advanced analytics, and standardized validation frameworks will further enhance our ability to develop biomarkers that accurately inform both prognosis and treatment selection across therapeutic areas.

In the pursuit of efficient and meaningful drug development, the precise use of biomarkers, surrogate endpoints, and clinical endpoints is critical for evaluating therapeutic interventions. These concepts form a hierarchy of measurement, with each level serving a distinct purpose in clinical research and regulatory decision-making. A biomarker is a defined characteristic that is measured as an indicator of normal biological processes, pathogenic processes, or responses to an exposure or intervention [16]. Biomarkers encompass a wide range of measurements, including molecular, histologic, radiographic, or physiologic characteristics [16]. The Biomarkers, EndpointS, and other Tools (BEST) resource categorizes biomarkers into seven primary types: susceptibility/risk, diagnostic, monitoring, prognostic, predictive, pharmacodynamic/response, and safety biomarkers [16].

A surrogate endpoint is a specific type of biomarker intended to substitute for a clinical endpoint [17]. It is defined as "a biomarker intended to substitute for a clinical endpoint," where a clinical endpoint is "a characteristic or variable that reflects how a patient feels, functions, or survives" [17]. The use of a surrogate endpoint is fundamentally an exercise in extrapolation, where changes induced by a therapy on the surrogate are expected to reflect changes in a clinically meaningful outcome [18] [19]. In contrast, a clinical endpoint (also known as a clinically meaningful endpoint or true endpoint) provides a direct assessment of a patient's health status, measuring how a patient feels, functions, or survives [19]. These endpoints represent outcomes that matter most to patients, such as overall survival, reduction in pain, or improved physical function.

Hierarchical Relationship and Distinctions

The Conceptual Hierarchy

The relationship between biomarkers, surrogate endpoints, and clinical endpoints is inherently hierarchical. All surrogate endpoints are biomarkers, but not all biomarkers qualify as surrogate endpoints [17]. This hierarchy exists because a surrogate endpoint must undergo a rigorous validation process to ensure that treatment effects on the surrogate reliably predict clinical benefit [19]. A widely accepted four-level hierarchy for endpoints categorizes them as follows [19]:

- Level 1: A true clinical efficacy measure (e.g., overall survival, how a patient feels/functions/survives).

- Level 2: A validated surrogate endpoint for a specific disease setting and class of interventions.

- Level 3: A non-validated surrogate established as "reasonably likely to predict clinical benefit."

- Level 4: A correlate that is a measure of biological activity but not established to be at a higher level.

This structured approach helps clinical researchers and regulators appropriately interpret trial results based on the type of endpoint used.

Distinguishing Prognostic and Predictive Biomarkers

Within biomarker classification, understanding the distinction between prognostic and predictive biomarkers is essential for personalized medicine. A prognostic biomarker provides information about the likely natural history of a disease irrespective of therapy [6] [20]. It offers insight into the overall disease outcome, such as the risk of recurrence or progression. In contrast, a predictive biomarker indicates the likelihood of benefit from a specific therapeutic intervention [6] [20]. It helps identify which patients are most likely to respond to a particular treatment.

To visualize the fundamental hierarchical relationship between these core concepts and the distinction between prognostic and predictive biomarkers, the following diagram provides a clear structural overview:

A single biomarker can sometimes serve both prognostic and predictive functions. For example, HER2 overexpression in breast cancer initially identified patients with poorer prognosis (prognostic) but now primarily guides treatment with HER2-targeted therapies (predictive) [20]. Similarly, β-HCG and α-fetoprotein in male germ cell tumors help monitor for recurrence (prognostic) and guide decisions about adjuvant chemotherapy (predictive) [20].

Comparative Characteristics Table

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of clinical endpoints, surrogate endpoints, and general biomarkers:

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Endpoints in Clinical Research

| Characteristic | Clinical Endpoint | Surrogate Endpoint | General Biomarker |

|---|---|---|---|

| Definition | Direct measure of how a patient feels, functions, or survives [17] [19] | Biomarker intended to substitute for a clinical endpoint [17] | Measured indicator of biological processes, pathogenesis, or treatment response [16] |

| Primary Role | Direct assessment of treatment benefit | Predict clinical benefit; accelerate drug development [21] | Diagnosis, prognosis, monitoring, safety assessment [16] |

| Validation Requirements | Content validity; reliability; sensitivity to intervention [19] | Analytical validation; clinical validation; surrogate relationship evaluation [22] | Analytical validity; clinical validity for intended use [23] |

| Examples | Overall survival, stroke incidence, pain relief [19] | Blood pressure (for stroke risk), LDL-C (for cardiovascular events) [21] [22] | PSA levels, tumor grade, genetic mutations [17] [20] |

| Level in Hierarchy | Level 1 [19] | Level 2 (validated) or Level 3 (reasonably likely) [19] | Level 4 (or lower levels if validated as surrogate) [19] |

| Regulatory Acceptance | Gold standard for definitive trials [19] | Accepted when validated; basis for ~45% of new drug approvals (2010-2012) [21] | Varies by context of use and validation level |

Validation Frameworks and Methodologies

Validating Surrogate Endpoints

For a biomarker to be accepted as a surrogate endpoint, it must undergo rigorous evaluation. The validation process includes analytical validation (assessing assay sensitivity and specificity), clinical validation (demonstrating ability to detect or predict disease), and assessment of clinical utility [22]. The International Conference on Harmonisation guidelines propose evaluating three levels of association for surrogate endpoints: (1) biological plausibility, (2) individual-level association (predicting disease course in individual patients), and (3) study-level association (predicting treatment effects on the final outcome based on effects on the surrogate) [24].

Statistical methods for validating surrogate endpoints often involve meta-analytic approaches using data from multiple historical randomized controlled trials [24] [18]. The Daniels and Hughes method uses a bivariate meta-analysis to evaluate the association pattern between treatment effects on the surrogate and final outcomes [24]. A zero-intercept random-effects linear regression model can be applied to historical trial data to establish whether the surrogate endpoint reliably predicts effects on the clinical outcome [18].

Criteria for Surrogate Endpoint Validation

Several statistical and biological criteria should be satisfied for a surrogate endpoint to be considered valid:

Statistical Criteria:

- Acceptable sample size multiplier: The sample size needed for predicting treatment effect on the true endpoint via the surrogate should be practically feasible [18].

- Prediction separation score >1: Indicates that the effect of treatment on the surrogate is informative for the effect on the true endpoint [18].

- Slope (λ₁) ≠ 0: Establishes association between treatment effects on surrogate and final outcome [24].

- Conditional variance (ψ²) approaching zero: Suggests the true effect on the final outcome can be well-predicted from the effect on the surrogate [24].

- Intercept (λ₀) = 0: Ensures that no treatment effect on the surrogate implies no effect on the final outcome [24].

Biological/Clinical Criteria:

FDA Biomarker Qualification Process

The FDA's Biomarker Qualification Program employs a structured, collaborative approach to qualify biomarkers for use in drug development. This formal regulatory process ensures that a biomarker can be relied upon for a specific interpretation and application within a stated Context of Use (COU) [16]. The qualification process involves three stages:

- Stage 1: Letter of Intent - Initial submission describing the biomarker, proposed COU, and unmet drug development need [16].

- Stage 2: Qualification Plan - Detailed proposal for biomarker development to support qualification for the proposed COU [16].

- Stage 3: Full Qualification Package - Comprehensive compilation of supporting evidence for FDA's qualification decision [16].

Upon successful qualification, the biomarker may be used in any CDER drug development program within the qualified COU to support regulatory approval of new drugs [16].

Applications, Challenges, and Research Tools

Advantages and Applications

The appropriate use of biomarkers and surrogate endpoints offers significant advantages in drug development:

- Efficiency: Surrogate endpoints are often cheaper, easier, and quicker to measure than clinical endpoints [17]. For example, blood pressure measurement is far more efficient than long-term stroke mortality data collection [17].

- Smaller sample sizes: Clinical trials using surrogate endpoints typically require fewer participants [17]. A blood pressure trial might need only 100-200 patients, whereas a stroke prevention trial would require thousands [17].

- Earlier measurement: Surrogate endpoints can be assessed much sooner than long-term clinical outcomes [17], potentially accelerating drug development.

- Ethical considerations: In some cases, using biomarkers avoids ethical problems associated with waiting for clinical endpoints to manifest [17]. For example, in paracetamol overdose, plasma paracetamol concentration guides treatment decisions without waiting for actual liver damage [17].

- Personalized medicine: Predictive biomarkers enable selection of patients most likely to benefit from specific targeted therapies, particularly in oncology [23] [20].

Limitations and Cautions

Despite their advantages, significant challenges and limitations exist:

- Pathophysiological complexity: Surrogate endpoints are most reliable when disease pathophysiology and intervention mechanism are thoroughly understood [17]. Without this understanding, pitfalls await.

- Historical failures: Several biomarkers have failed as surrogates despite strong biological rationale. For example:

- Context dependence: A surrogate endpoint validated for one class of interventions may not apply to another, even within the same disease area [24].

- Statistical issues: Using surrogate endpoints as entry criteria can introduce heterogeneous variance and regression to the mean, potentially reducing study power [17].

- Safety detection: Smaller sample sizes in trials using surrogate endpoints may be insufficient to detect rare but serious adverse effects [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Biomarker Research

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Primary Research Function |

|---|---|---|

| Genomic Platforms | Array-based hybridization assays; Next-generation DNA sequencing [23] | Identification of molecular targets; development of prognostic/predictive biomarkers |

| Gene-Expression Classifiers | Oncotype DX (21-gene assay) [23] | Prognostic stratification; prediction of recurrence risk |

| Immunohistochemical Tests | Estrogen receptor status; HER2 amplification status [23] [20] | Predictive biomarker assessment for treatment selection |

| Laboratory Assays | Serum TSH; INR with warfarin; autoantibodies; C. difficile toxin [17] | Diagnostic, monitoring, and safety biomarkers |

| Imaging Technologies | MRI scans (e.g., white dots for multiple sclerosis lesions) [17] | Radiographic biomarkers for diagnosis and disease monitoring |

| Physiological Measurements | Blood pressure; FEV1; peak expiratory flow rate [17] | Physiological biomarkers for disease status and treatment response |

Biomarkers, surrogate endpoints, and clinical endpoints form an essential hierarchy in clinical research and drug development. While biomarkers serve broad purposes across diagnosis, prognosis, and monitoring, surrogate endpoints represent a specific subclass of biomarkers that undergo rigorous validation to substitute for clinical endpoints. The distinction between prognostic biomarkers (informing likely disease course) and predictive biomarkers (identifying patients likely to respond to specific treatments) is particularly crucial for advancing personalized medicine. Despite the efficiency gains offered by surrogate endpoints, their validation requires comprehensive evidence that treatment effects on the surrogate reliably predict meaningful clinical benefits. As biomarker science evolves with new genomic technologies and analytical methods, these tools will continue to transform drug development, enabling more targeted therapies and refined treatment selection for individual patients.

In the era of precision medicine, biomarkers are indispensable tools that provide an objectively measured indicator of normal biological processes, pathogenic processes, or pharmacological responses to therapeutic interventions [25]. The clinical utility of biomarkers is primarily categorized into two distinct functions: prognostic and predictive. Prognostic biomarkers provide information about the patient's overall cancer outcome regardless of therapy, identifying the likelihood of a clinical event, disease recurrence, or progression in patients who have the disease or medical condition of interest [6] [26]. In contrast, predictive biomarkers identify individuals who are more likely than similar individuals without the biomarker to experience a favorable or unfavorable effect from exposure to a medical product or environmental agent, providing information on the effect of a therapeutic intervention [6] [26].

The distinction between these biomarker types has profound clinical implications. For example, in breast cancer, estrogen receptor (ER) and progesterone receptor (PR) expression serve as both prognostic and predictive biomarkers—patients with ER+/PR+ tumors have better survival (prognostic) and are more likely to benefit from endocrine therapy (predictive) [26]. Similarly, HER2/neu amplification in breast cancer indicates a more aggressive tumor (prognostic) and predicts response to trastuzumab treatment (predictive) [26]. Understanding this distinction is critical for proper patient stratification and treatment selection in clinical practice.

Performance Comparison of Multi-Level Biomarker Data

Cancer Subgroup Classification Accuracy

Advanced technologies now enable the measurement of molecular data at various levels of gene expression, including genomic, transcriptomic, and translational levels [27]. However, information carried by one level of gene expression is not similar to another, as evidenced by the low correlation observed between different molecular levels such as transcriptome and proteome data [28]. This fundamental insight has driven interest in integrated multi-omics approaches for precision medicine applications.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Single vs. Multi-Omic Data in Cancer Subgroup Classification

| Cancer Type | Transcriptome Only | miRNA Only | Methylation Only | Proteome Only | Integrated Multi-Omic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast Cancer | >90% accuracy [28] | Data available [27] | Data available [27] | >90% accuracy [28] | Comprehensive analysis [27] |

| Multiple Cancers (9 types) | High accuracy in most cancers [28] | Performance varies [27] | Performance varies [27] | High accuracy in most cancers [28] | Potential performance improvement [28] |

Research demonstrates that for many cancers, even a single molecular level can predict corresponding cancer subgroups with very high accuracy (exceeding 90%) [28]. The selection of appropriate machine learning algorithms significantly impacts classification performance, with kernel- and ensemble-based algorithms consistently outperforming other methodologies across diverse gene-expression datasets [29]. The integration of multi-omic data represents a promising approach to potentially enhance classification accuracy beyond what can be achieved with single-omic data sources [27].

Algorithm Performance for Biomarker Discovery

The high-dimensional nature of genomic data, where the number of features (p) far exceeds the number of samples (n), creates unique computational challenges collectively known as the "n << p" problem [28] [30]. Feature selection and machine learning algorithm selection are critical components in addressing this challenge and deriving robust biomarkers from complex molecular data.

Table 2: Machine Learning Algorithm Performance for Gene-Expression Classification

| Algorithm Type | Performance Characteristics | Best For | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kernel-Based Algorithms | Consistently high performance across datasets [29] | Complex pattern recognition | Computational intensity |

| Ensemble Methods | Top-performing category [29] | High-dimensional data | Model interpretability |

| Logistic Regression | Best average rank overall [29] | General-purpose applications | Poor performance in 4.9% of cases [29] |

| PPLasso | Outperforms traditional Lasso for correlated biomarkers [30] | Prognostic and predictive biomarker identification | Continuous endpoints only |

Hyperparameter optimization and feature selection typically improve predictive performance, with univariate feature-selection algorithms often outperforming more sophisticated methods [29]. The PPLasso method represents a significant advancement specifically designed to identify both prognostic and predictive biomarkers in high-dimensional genomic data where biomarkers are highly correlated, simultaneously integrating both effects into a single statistical model [30].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Multi-Omic Data Integration Protocol

Comprehensive cancer subgroup classification requires systematic integration of diverse molecular data types. The following protocol outlines the methodology for such integrated analysis:

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing:

- Source multi-level gene expression data from curated repositories such as The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), which contains pan-genomic data from numerous cancers with multiple omic measurements [28]

- Include transcriptome, miRNA, methylation, and proteome data types for comprehensive coverage

- Address the "n << p" problem through feature selection methods such as Fisher ratio, which assumes Gaussian distribution and selects top features based on means and standard deviations [28]

Model Building and Validation:

- Implement multiple classification algorithms representing diverse machine learning methodologies

- Apply nested cross-validation to evaluate the effects of hyperparameter optimization and feature selection

- Compare performance between models using single-omic data versus integrated multi-omic data

- Validate identified features for biological relevance across different gene expression levels [28]

This experimental approach has demonstrated that sets of genes discriminant in one gene level may not be discriminant in other levels, highlighting the importance of multi-level analysis [28].

Prognostic and Predictive Biomarker Identification

The PPLasso method provides a specialized statistical framework for simultaneous identification of prognostic and predictive biomarkers:

Statistical Modeling:

- Format the identification problem as variable selection in an ANCOVA (Analysis of Covariance) type model

- Include both treatment-specific effects (predictive components) and general biomarker effects (prognostic components)

- Account for potential correlation between biomarkers across different treatments [30]

Correlation Handling:

- Transform the design matrix to remove correlations between biomarkers before applying generalized Lasso

- Overcome limitations of traditional Lasso, which struggles when biomarkers are highly correlated

- Employ Precision Lasso approach that assigns similar weights to correlated variables [30]

Validation Framework:

- Conduct extensive numerical experiments comparing PPLasso to traditional Lasso and extensions

- Evaluate performance metrics including biomarker selection accuracy and model robustness

- Apply to publicly available transcriptomic and proteomic data for real-world validation [30]

This methodology specifically addresses the challenge of identifying both prognostic and predictive biomarkers in high-dimensional settings where traditional methods may fail.

Signaling Pathways and Technical Workflows

Multi-Omic Data Integration Workflow

Diagram 1: Multi-Omic Data Integration Workflow for Cancer Classification. This workflow illustrates the process from sample collection through multi-omic integration for cancer subgroup classification, highlighting the parallel processing of different molecular data types.

Prognostic vs Predictive Biomarker Identification

Diagram 2: Prognostic vs Predictive Biomarker Identification Pathway. This diagram outlines the critical pathway for distinguishing prognostic versus predictive biomarkers, requiring comparison of treatment to control in patients with and without the biomarker.

Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Biomarker Discovery and Validation

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Platforms | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Resources | The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) | Provides curated pan-genomic data from multiple cancers | Multi-omic cancer subgroup classification [27] [28] |

| UK Biobank Metabolomic Data | World's largest metabolomic dataset (~250 metabolites in 500,000 volunteers) | Disease risk prediction, drug discovery [31] | |

| Analytical Platforms | Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS, GC-MS) | High-sensitivity metabolite measurement and quantification | Metabolomics, proteomics [32] |

| Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) | Molecular structure determination and metabolite quantification | Metabolomics with structural insights [32] | |

| Next-Generation Sequencing | High-throughput DNA and RNA sequencing | Genomic and transcriptomic biomarker discovery [33] | |

| Computational Tools | PPLasso R Package | Simultaneous selection of prognostic and predictive biomarkers | High-dimensional genomic data with correlated features [30] |

| ShinyLearner Tool | Benchmark comparison of classification algorithms | Algorithm selection for gene-expression classification [29] | |

| Feature Selection Methods | Fisher Ratio | Selects features based on means and standard deviations | Pre-processing high-dimensional omic data [28] |

The integration of multi-level biomarker data represents a transformative approach in modern precision medicine, enabling more accurate disease classification and patient stratification than single-omic approaches. Through comprehensive performance comparisons, we have demonstrated that while individual molecular levels often achieve high classification accuracy, integrated multi-omic strategies provide a more comprehensive biological understanding. The distinction between prognostic and predictive biomarkers remains clinically essential, with advanced statistical methods like PPLasso offering robust solutions for identifying both biomarker types in high-dimensional data. As metabolomic, proteomic, and genomic datasets continue to expand—exemplified by resources like UK Biobank—and as analytical technologies advance, researchers and drug development professionals are increasingly equipped to develop sophisticated biomarker panels that optimize therapeutic decision-making and patient outcomes.

The Evolving Role of Biomarkers in Precision Medicine and Proactive Health Management

The landscape of modern medicine is undergoing a fundamental transformation, shifting from traditional disease diagnosis and treatment models toward health maintenance approaches based on prediction and prevention [25]. This paradigmatic shift toward proactive health management is grounded in the biopsychosocial medical model, emphasizing early health risk identification and implementation of targeted interventions to prevent disease onset or delay progression [25]. Biomarkers—defined as objectively measurable indicators of biological processes—serve as the cornerstone of this transformation, providing crucial biological signposts that reveal underlying health conditions and enabling more precise medical interventions [34].

The classification of biomarkers extends beyond simple diagnostic applications to include prognostic biomarkers that forecast disease outcomes independent of treatment, and predictive biomarkers that indicate likely benefit from specific therapeutic interventions [20]. Understanding this distinction is critical for researchers and drug development professionals, as it directly influences clinical trial design, patient stratification strategies, and therapeutic development pathways. The rapid expansion of molecular characterization efforts has permitted the development of clinically meaningful biomarkers that help define optimal therapeutic strategies for individual patients, particularly in oncology where biomarkers have transformed treatment protocols for conditions like HER2-positive breast cancer and EGFR-mutated lung cancer [34].

Biomarker Fundamentals: Classification and Clinical Utility

Defining Biomarker Types and Applications

Biomarkers serve as measurable indicators within the body, appearing in blood, tissue, or other biological samples, providing crucial data about normal processes, disease states, and treatment responses [34]. Their role in healthcare continues to evolve, driving innovations in personalized medicine and therapeutic development. The classification system enables healthcare teams to develop targeted, effective treatment strategies.

Table: Biomarker Classification and Clinical Applications

| Biomarker Type | Primary Function | Clinical Utility | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnostic | Identifies or confirms a current disease state | Determines the presence or absence of disease | Beta-amyloid for Alzheimer's disease [34] |

| Prognostic | Provides information on likely disease outcome irrespective of treatment | Informs about natural disease history and overall outcome | HER2 overexpression in breast cancer (originally identified as poor prognosis) [20] |

| Predictive | Indicates likelihood of response to a specific treatment | Guides treatment selection by predicting therapeutic efficacy | Estrogen receptors in breast cancer predicting response to antiestrogen therapy [20] |

| Pharmacodynamic | Measures biological response to therapeutic intervention | Monitors drug activity and helps determine optimal dosing |

The distinction between prognostic and predictive biomarkers carries significant clinical implications. A single factor may serve both functions, as demonstrated by HER2 overexpression in breast cancer, which initially identified patients with poor prognosis but now predicts response to targeted therapies [20]. Similarly, β-HCG and α-fetoprotein in male germ cell tumors provide both prognostic information through early recognition of disease recurrence and predictive value by indicating when to initiate known effective cytotoxic drugs [20].

Establishing Clinically Relevant Biomarkers

Developing reliable biomarkers requires integrating multidisciplinary approaches and multi-level validation [25]. The advancement of big data and artificial intelligence technologies has transformed biomarker research from hypothesis-driven to data-driven approaches, expanding potential marker identification [25]. A systematic biomarker validation process encompasses discovery, validation, and clinical validation phases, ensuring research findings' reliability and clinical applicability.

Multi-omics integration methods serve a crucial role in this process, developing comprehensive molecular disease maps by combining genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics data [25]. This approach identifies complex marker combinations that traditional methods might overlook. Temporal data holds distinct value in biomarker research, as longitudinal cohort studies capturing markers' dynamic changes over time provide more comprehensive predictive information than single time-point measurements [25].

Methodological Approaches: From Discovery to Clinical Implementation

Biomarker Development Pipeline

Biomarker research follows a structured pipeline to ensure clinical validity and utility. Researchers should understand and explicitly address what stage of biomarker research they are conducting, as each phase has distinct objectives and requirements [8]. The development process can be partitioned into four sequential phases:

- Discovery Phase: Initial identification of biomarkers associated with pathology, assessment of biological plausibility, and measurement reliability [8]

- Translation Phase: Evaluation of how effectively the biomarker separates diseased from normal patients, or different risk categories [8]

- Single-Center Studies: Assessment of clinical utility in practice within a controlled setting [8]

- Multi-Center Studies: Determination of whether clinical utility maintains across multiple centers and assessment of cost-effectiveness [8]

A critical challenge in biomarker development is adequately powering studies to minimize false-positive results. Traditional "rule of 10" guidelines suggest that studies developing multivariable models should examine approximately one biomarker per 10 events of the least frequent outcome [8]. However, many imaging biomarker studies are characterized by "fishing trips" to identify viable biomarkers without prior hypotheses, tested in underpowered studies using incorrect methods [8]. A recent systematic review of radiomics research found an average type-I error rate (false-positive results) of 76%, largely due to inadequate sample size compared to the number of variables studied [8].

Statistical Considerations and Cut-Point Optimization

Selecting optimal cut-points for biomarkers represents a critical methodological challenge in diagnostic medicine. Several methods of cut-point selection have been developed based on ROC curve analysis, with the most prominent being Youden, Euclidean, Product, Index of Union (IU), and diagnostic odds ratio (DOR) methods [35]. Each method employs unique definition criteria in ROC space, and their performance varies depending on underlying distributions and degree of separation between diseased and non-diseased populations.

Simulation studies comparing these methods under different distribution pairs, degrees of overlap, and sample size ratios have revealed important performance characteristics [35]. With high AUC, the Youden method may produce less bias and MSE, but for moderate and low AUC, Euclidean has less bias and MSE than other methods [35]. The IU method yielded more precise findings than Youden for moderate and low AUC in binormal pairs, but its performance was lower with skewed distributions [35]. In contrast, cut-points produced by DOR were extremely high with low sensitivity and high MSE and bias [35].

Innovative Trial Designs for Biomarker Validation

Novel clinical trial designs are emerging to address the challenges of biomarker validation. The Single-arm Lead-In with Multiple Measures (SLIM) design incorporates repeated biomarker assessments over a short follow-up period to address within-subject variability [36]. This approach is particularly valuable for early-phase trials of brief duration where changes in clinical and functional outcomes are unlikely to be observed.

The SLIM design involves repeated biomarker assessments during both placebo lead-in and post-treatment periods, minimizing between-subject variability and improving the precision of within-subject estimates [36]. Simulation studies demonstrate that this design can substantially reduce required sample sizes compared to traditional parallel-group designs, thereby lowering the recruitment burden [36]. This design is well suited for early-phase, short-duration trials but is not suitable for cognitive tests or other outcomes prone to practice or placebo effects [36].

Technological Innovations Driving Biomarker Discovery

AI and Machine Learning Applications

Artificial intelligence is radically transforming pharmaceutical biomarker analysis, revealing hidden biological patterns that improve target discovery, patient selection, and trial design [37]. After decades of relying on traditional biomarkers and statistical models to inform early-stage research, AI is beginning to reshape how we discover targets, stratify patients, and design clinical trials [37]. AI-driven pathology tools and biomarker analysis provide deeper biological insights and help clinical decision-making in fields as diverse as oncology, where the lack of reliable biomarkers to personalize treatment remains a major challenge [37].

The application of AI for biomarker discovery is particularly evident in digital pathology. Research demonstrates that AI can uncover prognostic and predictive signals in standard histology slides that outperform established molecular and morphological markers [37]. For instance, at DoMore Diagnostics, AI-based digital biomarkers for colorectal cancer prognosis have been developed that can stratify patients according to their risk profiles, potentially avoiding unnecessary adjuvant chemotherapy for low-risk patients [37].

Multi-Omics Integration and Advanced Analytics

Modern biomarker development leverages sophisticated technological platforms that enhance detection accuracy and reliability. The integration of advanced analytics with traditional clinical expertise creates a powerful framework for personalized medicine [34]. Multi-omics approaches are emerging as powerful tools, synthesizing insights from genomics, proteomics, and related fields to enhance diagnostic precision [34]. The genomic biomarker sector shows particular promise, with projections indicating growth to $14.09 billion by 2028, driven by advancements in personalized medicine [34].

Table: Advanced Biomarker Detection Technologies

| Technology Platform | Primary Applications | Key Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Next-Generation Sequencing | Genomic biomarker discovery, mutational analysis | Comprehensive genomic assessment, decreasing costs | Data interpretation challenges, storage requirements |

| Mass Spectrometry-Based Proteomics | Protein biomarker identification and validation | High specificity and sensitivity, quantitative analysis | Complex sample preparation, technical expertise needed |

| Liquid Biopsy Platforms | Non-invasive monitoring, treatment response assessment | Minimal invasiveness, serial monitoring capability | Sensitivity limitations for early detection |

| Digital Pathology with AI | Tumor microenvironment analysis, predictive signal detection | Uncovers patterns beyond human perception, uses existing samples | Validation requirements, regulatory considerations |

The integration of multi-omics data with advanced analytical methods has improved early Alzheimer's disease diagnosis specificity by 32%, providing a crucial intervention window [25]. Similarly, in oncology, AI-driven analysis of whole-slide images has demonstrated utility in predicting clinical benefit from immunotherapy in colorectal cancer [38].

Comparative Analysis of Biomarker Performance in Clinical Applications

Oncology Applications

Oncology represents the most significant disease indication category for biomarkers, accounting for 35.1% of the genomic biomarkers market [33]. Biomarkers have transformed cancer care by enabling more precise patient stratification and treatment selection. The comparative performance of different biomarker approaches in oncology reveals distinct advantages and limitations across technologies.

Table: Biomarker Performance in Oncology Applications

| Cancer Type | Biomarker Class | Clinical Application | Performance Metrics | Comparative Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colorectal Cancer | AI-based digital pathology | Predict benefit from atezolizumab + FOLFOXIRI-bevacizumab | Biomarker-high pts: mPFS 13.3 vs 11.5 mos; mOS 46.9 vs 24.7 mos [38] | Identifies patients likely to benefit from immunotherapy combinations |

| ALK+ NSCLC | AI-based imaging biomarkers | Predict PFS based on early brain metastasis response | Low- vs high-risk: 33.3 mo vs 7.8 mo PFS (HR 0.34) [38] | Earlier prediction than RECIST assessments |

| Resectable NSCLC | Radiomics + ctDNA | Predict complete pathological response | AUC 0.82 (radiomics alone); AUC 0.84 (with ctDNA) [38] | Non-invasive predictive tool for treatment response |

| Mesothelioma | AI-based imaging + genomic ITH | Predict response to niraparib | PFS HR 0.19 in high ITH vs 1.40 in low ITH [38] | Combines structural and genomic information for prediction |

The integration of multiple biomarker modalities demonstrates enhanced predictive power compared to single-platform approaches. In mesothelioma, the combination of AI-derived tumor volume assessment from CT scans with genomic intratumoral heterogeneity measures created a dual AI-genomic approach with multiple applications for predicting prognosis and selecting patients likely to benefit from specific treatments [38].

Neurological and Chronic Disease Applications

Beyond oncology, biomarkers are transforming management of neurological disorders, cardiovascular diseases, and other chronic conditions. Neurological biomarker research is gaining momentum, particularly in North America, with expanding applications for improved diagnostic accuracy and treatment optimization [34]. In Alzheimer's disease and related dementias, plasma biomarkers are increasingly used as surrogate outcomes in clinical trials due to their non-invasive nature [36].

The treatment selection segment represents 50.2% of the personalized medicine biomarker market share, demonstrating the growing confidence in biomarker-guided decision-making across therapeutic areas [34]. The global personalized medicine biomarker market is projected to reach USD 72.7 billion by 2033, reflecting expanding applications beyond oncology into neurological, cardiovascular, and autoimmune conditions [34].

Implementation Challenges and Solution Frameworks

Analytical and Validation Challenges

Despite promising technological advances, significant challenges persist in effectively integrating biomarker data, developing reliable predictive models, and implementing these in clinical practice [25]. The biomarker development pipeline faces multiple hurdles, with a 2014 review identifying a "major disconnect between the several hundred thousand published candidate biomarkers and the less than one-hundred US FDA-approved companion diagnostics" [8]. Very few biomarkers undergo any assessment beyond the articles first proposing them, with a recent systematic review finding that most multivariable models incorporating novel imaging biomarkers are never evaluated by other researchers [8].

Common analytical challenges include:

- High-dimensional data: Investigating numerous biomarker candidates with limited sample sizes increases false discovery rates [8]

- Within-subject variability: Biological and measurement error can obscure true treatment effects [36]

- Standardization limitations: Testing methods vary significantly across laboratories, creating inconsistency in results [33]

- Data heterogeneity: Multimodal data integration requires sophisticated analytical approaches [25]

Clinical Translation Barriers

Translating biomarker research into clinical practice faces substantial implementation barriers:

- Regulatory complexity: Approval processes for genomic biomarker tests are lengthy, with each region having its own regulatory framework [33]

- Clinical adoption hurdles: Pathologists, clinicians, and trial sponsors need to trust that AI-generated biomarkers are reproducible, interpretable, and clinically actionable [37]

- Workforce limitations: There is a limited supply of trained geneticists and bioinformaticians, slowing clinical adoption [33]

- Cost constraints: The expense of genomic testing remains high due to advanced sequencing tools and skilled personnel requirements [33]

To address these challenges, researchers have proposed integrated frameworks prioritizing three pillars: multi-modal data fusion, standardized governance protocols, and interpretability enhancement [25]. This systematic approach addresses implementation barriers from data heterogeneity to clinical adoption, enhancing early disease screening accuracy while supporting risk stratification and precision diagnosis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Core Laboratory Materials and Platforms

Successful biomarker research requires specialized reagents and platforms that ensure reproducible, high-quality results. The following table outlines essential research reagent solutions for biomarker development and validation.

Table: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Biomarker Development

| Reagent/Platform | Primary Function | Key Applications | Considerations for Selection |

|---|---|---|---|

| Next-Generation Sequencing Kits | Comprehensive genomic profiling | Genetic biomarker discovery, mutational analysis, tumor sequencing | Coverage depth, error rates, input DNA requirements |

| Multi-Omics Sample Preparation Kits | Standardized nucleic acid and protein extraction | Integrated genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic analysis | Compatibility across platforms, yield, purity |

| Automated Homogenization Systems | Standardized sample processing | Consistent biomarker extraction from diverse sample types | Throughput, cross-contamination prevention, sample volume range |

| High-Sensitivity Immunoassay Reagents | Low-abundance protein detection | Pharmacodynamic biomarkers, inflammatory markers | Dynamic range, specificity, multiplexing capability |

| Liquid Biopsy Collection Tubes | Stabilization of circulating biomarkers | ctDNA, exosome, and circulating cell preservation | Stability duration, compatibility with downstream assays |

| Digital Pathology Slide Preparation Kits | Tissue processing for AI-based analysis | Tumor microenvironment characterization, morphology quantification | Stain consistency, image clarity, compatibility with scanners |

Analytical and Computational Tools

Beyond wet laboratory reagents, biomarker research requires sophisticated analytical and computational solutions:

- Bioinformatic Pipelines: Specialized software for processing next-generation sequencing data, including alignment, variant calling, and annotation tools [25]

- AI and Machine Learning Platforms: Computational frameworks for developing predictive models from complex biomarker data, including deep learning algorithms for image analysis [37] [38]

- Statistical Analysis Packages: Software solutions for cut-point optimization, including implementations of Youden, Euclidean, Product, IU, and DOR methods [35]

- Multi-Omics Integration Tools: Computational platforms that enable synthesis of genomic, proteomic, and metabolomic data for comprehensive biomarker discovery [25]

Visualizing Biomarker Development Workflows

Biomarker Development Pipeline

AI-Enhanced Biomarker Analysis Workflow

The field of biomarker research continues to evolve rapidly, with several emerging trends shaping future development. The global genomic biomarkers market is projected to reach USD 17 billion by 2033, rising from USD 7.1 billion in 2023, with a CAGR of 9.1% expected during 2024-2033 [33]. This growth is supported by the shift toward precision medicine, with genomic biomarkers increasingly used to classify patients, forecast disease progression, and optimize therapy decisions [33].

Future directions in biomarker research include:

- Expansion to rare diseases: Applying predictive models to conditions with unmet diagnostic needs [25]

- Dynamic health monitoring: Incorporating continuous physiological data from wearable devices and other digital health technologies [25]

- Strengthened multi-omics approaches: Enhancing integrative analysis across biological layers [25]

- Longitudinal cohort studies: Capturing biomarker trajectories over extended periods [25]

- Edge computing solutions: Leveraging decentralized data handling for low-resource settings [25]

In conclusion, biomarkers represent a transformative framework in modern healthcare, offering powerful insights into human biology and disease. The distinction between prognostic and predictive biomarkers carries significant implications for clinical trial design and therapeutic development. While technological innovations like AI and multi-omics integration are accelerating biomarker discovery, implementation challenges remain. Researchers and drug development professionals must navigate these complexities while advancing the field toward more precise, personalized healthcare solutions.

Biomarker Development and Implementation: Technical Pathways and Clinical Applications

Methodological Frameworks for Biomarker Discovery and Validation

Biological markers, or biomarkers, are defined characteristics measured as indicators of normal biological processes, pathogenic processes, or responses to an exposure or intervention [39]. In modern oncology, biomarkers have become indispensable tools that enable a shift from one-size-fits-all treatments to precision medicine, where prevention, screening, and treatment strategies are customized to patients with similar molecular characteristics [39]. The clinical utility of biomarkers spans their application as prognostic indicators, which provide information about overall expected clinical outcomes regardless of therapy, and as predictive indicators, which inform the likely response to a specific treatment [39] [40]. This distinction forms the cornerstone of biomarker clinical utility assessment research, guiding therapeutic decision-making and clinical trial design.

The journey of a biomarker from discovery to clinical implementation is long and arduous, with only approximately 0.1% of potentially clinically relevant cancer biomarkers described in literature progressing to routine clinical use [41]. This high attrition rate underscores the critical importance of rigorous methodological frameworks that can systematically address challenges at each development stage. The evolving landscape of biomarker science now integrates cutting-edge technologies including liquid biopsies, multi-omics platforms, artificial intelligence, and advanced validation techniques that collectively enhance the reliability and clinical applicability of novel biomarkers [14] [42] [43].

Foundational Concepts: Prognostic versus Predictive Biomarkers

Understanding the fundamental distinction between prognostic and predictive biomarkers is essential for proper clinical utility assessment. These biomarker types differ in their clinical applications, methodological requirements for identification, and statistical validation approaches.

A prognostic biomarker provides information about the natural history of the disease and overall expected clinical outcomes independent of therapy [39]. For example, in non-squamous non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), STK11 mutation is associated with poorer outcomes regardless of treatment selection [39]. Prognostic biomarkers help stratify patients into different risk groups, which can inform disease monitoring intensity and patient counseling about expected disease course.

A predictive biomarker informs the likely response to a specific therapeutic intervention [39] [40]. The most important predictive biomarkers found for NSCLC include mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) gene [39]. The IPASS study demonstrated that patients with EGFR mutated tumors had significantly longer progression-free survival when receiving gefitinib compared to carboplatin plus paclitaxel, while patients with EGFR wildtype tumors had significantly shorter progression-free survival when receiving gefitinib [39]. This treatment-by-biomarker interaction is the hallmark of predictive biomarkers.

Table 1: Key Differences Between Prognostic and Predictive Biomarkers

| Characteristic | Prognostic Biomarker | Predictive Biomarker |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical Question | What is the likely disease course regardless of treatment? | Will this specific treatment benefit the patient? |

| Study Design Requirement | Can be identified in properly conducted retrospective studies | Must be identified using data from randomized clinical trials |

| Statistical Test | Main effect test of association between biomarker and outcome | Interaction test between treatment and biomarker |

| Clinical Application | Patient stratification by risk, intensity of monitoring | Treatment selection, therapy personalization |

| Example | STK11 mutation in NSCLC [39] | EGFR mutation for gefitinib response in NSCLC [39] |

| Regulatory Considerations | Demonstrates association with clinical outcomes | Demonstrates ability to predict response to specific intervention |

Methodological Frameworks for Biomarker Discovery

Biomarker Discovery Workflow and Technologies

The biomarker discovery process follows a multi-stage approach designed to systematically identify, test, and implement biological markers for enhanced disease diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment strategies [42]. The initial stage involves sample collection and preparation from relevant patient groups using proper handling and storage protocols to maintain sample integrity [42]. This is followed by high-throughput screening and data generation using technologies such as genomics, proteomics, and metabolomics to analyze large volumes of biological data and reveal patterns across numerous samples [42]. The subsequent data analysis and candidate selection phase employs bioinformatics and statistical tools to identify promising biomarker candidates that distinguish between diseased and healthy samples or indicate specific disease characteristics [42].

Diagram 1: Biomarker Discovery and Validation Workflow

Several advanced technological platforms have revolutionized biomarker discovery. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) enables high-throughput DNA sequencing, allowing researchers to rapidly analyze entire genomes and identify genetic mutations linked to disease progression and treatment responses [14] [42]. In colorectal cancer, NGS has been used to profile mutations across cancer-related genes, revealing that patients with wild-type profiles in these genes experienced longer progression-free survival when treated with cetuximab [42]. Mass spectrometry-based proteomics advances biomarker discovery by enabling precise identification and quantification of proteins linked to diseases, analyzing proteins in body fluids to pinpoint biomarkers for early diagnosis and monitoring of conditions like cancer and cardiovascular diseases [42]. Microarray technologies allow simultaneous measurement of thousands of gene expressions, enabling identification of disease-related biomarkers, particularly in cancer research where they help detect specific genetic changes associated with various cancer stages and types [42].

Key Considerations for Robust Discovery Studies

Several methodological considerations are critical during the discovery phase to ensure biomarker validity. The intended use of the biomarker (e.g., risk stratification, screening, diagnosis, prognosis, prediction of response to intervention, or disease monitoring) and the target population must be defined early in the development process [39]. The patients and specimens should directly reflect the target population and intended use, with careful attention to patient selection, specimen collection, specimen analysis, and patient evaluation to minimize bias [39].

Bias control represents one of the most crucial aspects of biomarker discovery. Bias can enter a study during patient selection, specimen collection, specimen analysis, and patient evaluation, potentially leading to failure in subsequent validation studies [39]. Randomization and blinding are two of the most important tools for avoiding bias. Randomization in biomarker discovery should control for non-biological experimental effects due to changes in reagents, technicians, machine drift, and other factors that can result in batch effects [39]. Specimens from controls and cases should be assigned to testing platforms by random assignment, ensuring equal distribution of cases, controls, and specimen age [39]. Blinding prevents bias induced by unequal assessment of biomarker results by keeping individuals who generate the biomarker data from knowing the clinical outcomes [39].

The analytical approach must be carefully planned to address study-specific goals and hypotheses. The analytical plan should be written and agreed upon by all research team members before data access to prevent data from influencing the analysis [39]. This includes pre-defining outcomes of interest, hypotheses to be tested, and criteria for success. When multiple biomarkers are evaluated, control of multiple comparisons should be implemented; measures of false discovery rate (FDR) are especially useful when using large-scale genomic or other high-dimensional data for biomarker discovery [39].

Methodological Frameworks for Biomarker Validation

Validation Pathways and Performance Metrics

Biomarker validation progresses through structured phases that establish analytical validity, clinical validity, and ultimately clinical utility. Analytical validation ensures the biomarker test accurately and reliably measures the intended analyte across specified sample matrices, assessing parameters including accuracy, precision, sensitivity, specificity, and reproducibility [41] [43]. The clinical validation phase demonstrates that the biomarker consistently correlates with or predicts clinical outcomes of interest [41] [43]. Finally, clinical utility establishes that using the biomarker in clinical decision-making improves patient outcomes or provides beneficial information for patient management [39] [40].

Table 2: Biomarker Validation Metrics and Their Interpretations

| Validation Metric | Definition | Interpretation | Common Assessment Methods |