Spatial Transcriptomics: Decoding the Tumor Microenvironment for Cancer Research and Therapy

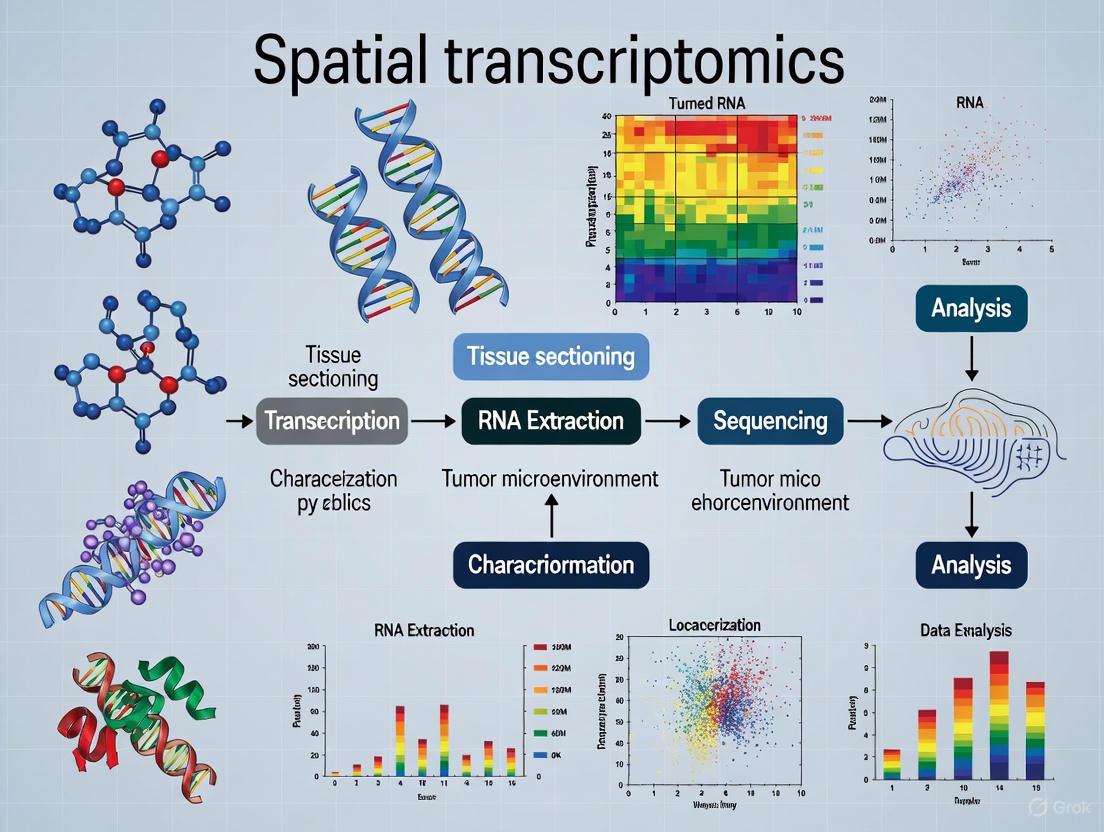

Spatial transcriptomics (ST) has emerged as a transformative technology that preserves the spatial context of gene expression within intact tissues, providing unprecedented insights into the complex architecture of the tumor...

Spatial Transcriptomics: Decoding the Tumor Microenvironment for Cancer Research and Therapy

Abstract

Spatial transcriptomics (ST) has emerged as a transformative technology that preserves the spatial context of gene expression within intact tissues, providing unprecedented insights into the complex architecture of the tumor microenvironment (TME). This review synthesizes current ST methodologies, their applications in characterizing tumor heterogeneity, immune cell interactions, and spatial cellular neighborhoods, and their growing impact on drug discovery and clinical translation. We explore foundational concepts of the TME, detail established and cutting-edge ST platforms like 10x Visium, GeoMx DSP, MERFISH, and Slide-seq, and address key technical challenges and computational solutions. By examining validation studies and comparative analyses across multiple cancer types, we highlight how spatial biology is reshaping our understanding of cancer mechanisms, identifying novel biomarkers, and informing the development of targeted therapies and immunotherapies for precision oncology.

The Spatial Landscape of Cancer: Foundational Principles of the Tumor Microenvironment

The tumor microenvironment (TME) is a dynamic ecosystem that co-evolves with malignant cells, playing a pivotal role in tumorigenesis, progression, therapeutic resistance, and metastasis [1] [2]. The traditional cancer cell-centric model of research has shifted to recognize the TME as a critical determinant of clinical outcomes [1]. This application note defines the core components of the TME and provides detailed protocols for their spatial characterization, framed within the context of advanced spatial transcriptomics research. Understanding the complex interplay between cellular and molecular elements within the TME provides the foundation for developing novel therapeutic strategies and overcoming treatment resistance in oncology [3].

Core Cellular Components of the TME

The TME comprises diverse cellular populations that exhibit remarkable plasticity and functional heterogeneity. The table below summarizes the key cellular components, their origins, primary functions, and markers.

Table 1: Cellular Constituents of the Tumor Microenvironment

| Cell Type | Origin | Key Functions in TME | Characteristic Markers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts (CAFs) | Local fibroblasts, mesenchymal stem cells, adipocytes, endothelial cells [1] | ECM remodeling, promotion of chemoresistance, immune reprogramming, support of cancer stemness [1] [3] | α-SMA, FAP, Fibronectin, Type I Collagen [3] |

| Tumor-Associated Macrophages (TAMs) | Peripheral blood monocytes, tissue-resident macrophages [1] | Duality: M1 (anti-tumor) vs. M2 (pro-tumor) polarization; regulation of tumor proliferation, invasion, angiogenesis, and immune evasion [1] [3] | CD68, CD163, CD206, SPP1 [4] [5] |

| T Cells | Thymus | Duality: Cytotoxic CD8+ T cells (anti-tumor) vs. Regulatory T cells (Tregs, immunosuppressive) [1] [3] | CD3, CD8 (Cytotoxic), CD4, FOXP3 (Tregs) [1] [4] |

| Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells (MDSCs) | Aberrant myeloid differentiation of hematopoietic stem cells [1] | Suppression of T cell function, driving tumor progression and chemoresistance [1] [3] | CD11b, Gr-1 (mouse); CD33, CD15 (human) [1] |

| Tumor-Associated Neutrophils (TANs) | Blood neutrophils recruited to tumor site [3] | Duality: N1 (anti-tumor) vs. N2 (pro-tumor) phenotypes; promotion of angiogenesis and metastasis [1] [3] | CD66b, CD15 [1] |

| B Cells | Bone Marrow | Production of pathogenic immunoglobulins that promote tumor cell invasion and lymphatic metastasis [6] | CD19, CD20 [6] |

| Endothelial Cells | Local vasculature, progenitor cells | Formation of new blood vessels (angiogenesis) to supply nutrients and oxygen [1] | CD31, VEGFR2 [1] |

Molecular and Non-Cellular Components

The functional output of the TME's cellular components is mediated by a complex network of secreted molecules and non-cellular structures.

Table 2: Molecular and Non-Cellular Components of the TME

| Component Category | Key Elements | Primary Functions in TME |

|---|---|---|

| Secreted Proteins | Cytokines, Chemokines, Growth Factors, Interferons, Extracellular Proteases [1] | Drive intercellular communication; promote tumor cell proliferation, invasion, survival, and immune evasion [1]. |

| Extracellular Matrix (ECM) | Collagen, Glycosaminoglycans (GAGs), Fibronectin, Laminin, Hyaluronan [7] [3] | Provides structural support; remodeled by CAFs and MMPs to facilitate tumor invasion and metastasis [1] [7]. |

| Metabolites | Lactate, Succinate, Itaconate, Arginine, Polyamines, Nucleotides, Fatty Acids [8] | Shape immune cell function; create an immunosuppressive microenvironment; fuel tumor growth via metabolic reprogramming (e.g., Warburg effect) [3] [8]. |

| Extracellular Vesicles | Exosomes, Microvesicles | Transfer of proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids (e.g., functional mtDNA, non-coding RNAs) between cells; mediate therapy resistance and pre-metastatic niche formation [1] [9] [3]. |

Signaling Pathways Governing TME Crosstalk

Complex signaling networks coordinate the interactions within the TME. The diagram below illustrates key pathways mediated by secreted factors.

Key Signaling Pathways in the TME

Advanced Spatial Profiling of the TME: Application Notes

High-Definition Spatial Transcriptomics Protocol

Spatial transcriptomics has revolutionized TME characterization by preserving the architectural context of gene expression. The following protocol is adapted from studies profiling colorectal cancer (CRC) using Visium HD [4].

Table 3: Protocol for Visium HD Spatial Transcriptomics on FFPE Tissue

| Step | Description | Critical Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Tissue Preparation | Section formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue blocks at 5-10 µm thickness. | Use fresh microtome blades to ensure section integrity and prevent RNA degradation. |

| 2. Probe Ligation | Perform whole-transcriptome probe hybridization and ligation on slides. | Optimize incubation time and temperature to ensure specific target capture. |

| 3. CytAssist Transfer | Use the CytAssist instrument to transfer ligated probes from tissue to the Visium HD slide. | The CytAssist controls reagent flow, minimizing lateral diffusion and ensuring spatial fidelity [4]. |

| 4. Library Construction & Sequencing | Generate sequencing libraries from captured probes and sequence on a compatible Illumina platform. | Aim for ~50,000 read pairs per spot (8µm bin) for robust gene detection. |

| 5. Data Analysis | Process data through Space Ranger pipeline. Bin 2µm data to 8µm or 16µm resolution for analysis. | Validate spatial accuracy using genes with known localization patterns (e.g., CLCA1 in colon glands) [4]. |

The experimental workflow for spatial TME characterization integrates multiple technologies, as shown below.

Spatial TME Analysis Workflow

Spatial ECM Characterization Protocol

The ECM is a critical non-cellular component of the TME. This protocol details the simultaneous visualization of collagen and glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) in CRC samples [7].

Table 4: Protocol for Spatial Characterization of ECM Collagen-GAG

| Reagent | Composition / Preparation | Function | Incubation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alcian Blue Solution | 1% Alcian Blue 8GX in 3% acetic acid, pH 2.5. | Stains sulfated and carboxylated GAGs blue. | 30 minutes at room temperature. |

| Picrosirius Red Solution | 0.1% Direct Red 80 in a saturated picric acid solution. | Stains collagen fibers red. | 60 minutes at room temperature. |

| Acidic Differentiation | 0.5% acetic acid solution. | Differentiates Alcian Blue staining, removing non-specific binding. | Rinse for 30 seconds after Alcian Blue step. |

Procedure:

- Deparaffinize and rehydrate FFPE tissue sections (5 µm) through xylene and graded ethanol series.

- Rinse in distilled water.

- Stain with Alcian Blue solution for 30 minutes.

- Rinse briefly in 0.5% acetic acid for differentiation.

- Rinse in distilled water.

- Stain with Picrosirius Red solution for 60 minutes.

- Rinse quickly in two changes of acidified water (0.5% acetic acid).

- Dehydrate rapidly through graded ethanol, clear in xylene, and mount with a resinous medium.

Imaging and Analysis: Image slides using brightfield microscopy. The distinct blue (GAGs) and red (collagen) colorations allow for straightforward spectral separation on digital imaging systems for subsequent quantification of distribution patterns and density [7].

Novel Mechanisms and Research Applications

Mitochondrial Transfer as an Immune Evasion Mechanism

A novel mechanism of immune evasion involves the transfer of mitochondria from cancer cells to T cells in the TME. This process can be investigated using the following experimental approach [9]:

- Fluorescent Labeling: Transduce cancer cells (e.g., melanoma cell lines) with a mitochondria-specific fluorescent protein (e.g., Mito-DsRed).

- Coculture System: Coculture labeled cancer cells with T cells (e.g., tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes) for 24-48 hours.

- Pathway Inhibition: Apply inhibitors to dissect transfer mechanisms:

- Cytochalasin B (5µM): Inhibits tunneling nanotube (TNT) formation.

- GW4869 (10µM): Blocks small extracellular vesicle (EV) release.

- Transwell Inserts (0.4µm): Prevent direct cell-cell contact.

- Flow Cytometry: Quantify the percentage of DsRed-positive T cells to measure mitochondrial transfer efficiency.

- Functional Assays: Assess metabolic changes (e.g., OXPHOS capacity) and functional status (e.g., cytokine production, senescence markers) in T cells that have received cancer cell mitochondria.

The process and functional consequences of mitochondrial transfer are summarized in the diagram below.

Mitochondrial Transfer Impairs T Cell Function

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 5: Essential Reagents for TME Spatial Characterization

| Reagent / Technology | Function / Application | Example Use in TME Research |

|---|---|---|

| Visium HD Spatial Gene Expression | Whole-transcriptome spatial analysis at single-cell-scale resolution (2µm features). | Mapping distinct macrophage (SPP1+) and T cell subpopulations in colorectal cancer niches [4]. |

| Xenium In Situ Gene Expression | Targeted, highly multiplexed in situ analysis for validation. | Orthogonal validation of gene expression patterns identified by Visium HD [4]. |

| CytAssist Instrument | Controls reagent flow for spatial assays. | Ensures accurate transfer of analytes from FFPE tissues to capture arrays, preserving spatial fidelity [4]. |

| Alcian Blue / Picrosirius Red | Dual histochemical staining for ECM components. | Simultaneous visualization and quantification of collagen and GAG spatial distribution [7]. |

| Mito-DsRed / MitoTracker Probes | Fluorescent labeling of mitochondria for live-cell imaging. | Tracking and quantifying mitochondrial transfer from cancer cells to T cells in coculture models [9]. |

| Cytochalasin B & GW4869 | Inhibitors of TNT formation and small EV release, respectively. | Mechanistic dissection of mitochondrial transfer pathways [9]. |

The tumor microenvironment is a complex and dynamic ecosystem where cellular components, molecular signals, and metabolic products interact to dictate disease progression and therapeutic response. Moving beyond a cancer cell-centric view is essential for advancing oncology research. The application of high-resolution spatial transcriptomics technologies, such as Visium HD, coupled with detailed molecular and histochemical protocols, provides an unprecedented ability to map these interactions within their native architectural context. This integrated understanding is critical for identifying novel therapeutic targets, developing biomarkers, and ultimately designing more effective, personalized cancer treatments that disrupt the tumor-promoting functions of the TME.

The Critical Role of Spatial Architecture in Tumor Progression and Therapy Response

Spatial transcriptomics has emerged as a revolutionary technology that integrates imaging, sequencing, and bioinformatics to precisely locate gene expression within tissue slices while preserving spatial context [10]. Unlike traditional bulk RNA sequencing or single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq), which requires tissue dissociation and loses spatial information, spatial transcriptomics enables researchers to quantify and illustrate gene expression in the spatial context of intact tissues [10]. This technological advancement provides unprecedented insights into the tumor microenvironment (TME), revealing cellular heterogeneity, cell-cell interactions, and spatial organization that profoundly influence tumor biology, progression, and therapy response [11] [12].

The spatial organization of the TME creates distinct ecological niches that regulate key cancer processes. Research has demonstrated that tumors exhibit conserved architectural patterns with specialized functional regions, particularly the tumor core (TC) and leading edge (LE), each characterized by unique transcriptional profiles, cellular compositions, and cell-cell communication networks [11]. Understanding this spatial architecture provides critical insights into disease mechanisms and reveals novel therapeutic opportunities for cancer treatment.

Key Spatial Architectures in Solid Tumors

Tumor Core versus Leading Edge Architectures

Integrative single-cell and spatial transcriptomic analyses of HPV-negative oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) have revealed that the tumor core and leading edge represent distinct transcriptional architectures with specialized biological functions:

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Tumor Core versus Leading Edge Architectures

| Feature | Tumor Core (TC) | Leading Edge (LE) |

|---|---|---|

| Transcriptional Profile | Tissue-specific | Conserved across cancer types |

| Clinical Prognosis | Associated with improved outcomes | Predicts worse survival across multiple cancers |

| Cellular Composition | Hypoxic regions, necrotic areas | Invasive fronts, immune cell interactions |

| Biological Processes | Cell stress pathways, metabolic adaptation | Invasion, immune modulation, metastasis |

| Therapeutic Implications | Potential sensitivity to metabolic inhibitors | May require targeted invasion inhibitors |

The leading edge gene signature consistently associates with worse clinical outcomes across multiple cancer types, highlighting the conservation of invasive mechanisms throughout cancer evolution [11]. Conversely, the tumor core signature demonstrates more tissue-specific characteristics while still maintaining associations with improved prognosis [11].

Pan-Cancer Conservation of Spatial Patterns

Research across 23 cancer types has revealed that certain spatial organizations represent fundamental biological principles in tumor evolution. The conservation of leading edge architecture across diverse cancer types suggests common mechanisms underlying tumor invasion and progression [11]. Additionally, studies of tumor-associated tertiary lymphoid structures (TA-TLS) have demonstrated conserved spatial patterns of immune organization across cancer types, with mature TLSs showing preferential enrichment of IgG+ plasma cells and specific endothelial cell phenotypes that influence immune recruitment [13].

Experimental Protocols for Spatial Architecture Analysis

Integrated Single-Cell and Spatial Transcriptomics Workflow

Table 2: Protocol for Comprehensive TME Spatial Analysis

| Step | Methodology | Key Outputs |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Tissue Preparation | Fresh frozen or FFPE tissue sections (5-10 μm thickness) | Preserved tissue architecture with RNA integrity |

| 2. Spatial Transcriptomics | Visium HD (10x Genomics) or similar platforms | Whole transcriptome data with spatial coordinates |

| 3. Single-Cell RNA Sequencing | Flex Gene Expression on adjacent tissue curls | Cell-type reference dataset without spatial context |

| 4. Data Integration | Computational integration of spatial and single-cell data | Cell type prediction in spatial contexts |

| 5. Spatial Mapping | Identification of tumor core, leading edge, and niche regions | Architecturally defined tissue domains |

| 6. Interaction Analysis | LIANA tool for ligand-receptor inference | Cell-cell communication networks in spatial context |

This integrated approach enables researchers to overcome the limitations of individual technologies, providing both high-resolution cellular data and crucial spatial context [12]. The reference scRNA-seq dataset ensures consistent cellular annotation across heterogeneous patient samples, while the spatial data preserves the architectural context of the TME.

Tumor Boundary Analysis Protocol

For specialized analysis of the tumor-stroma interface, which represents a critical zone for tumor invasion and immune interaction:

- Boundary Identification: Define tumor boundaries using H&E staining morphology and epithelial cell markers

- Peripheral Zone Selection: Select all barcoded spatial spots within 50 μm of periphery tumor cells [12]

- Cellular Composition Quantification: Calculate abundance of all cell types in boundary regions

- Subpopulation Clustering: Perform unsupervised clustering of cells within boundary regions

- Ligand-Receptor Analysis: Infer cell-cell communication using specialized tools (e.g., LIANA) [12]

This methodology has revealed that cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) represent the most prominent stromal cell type in border regions, while macrophages constitute the most abundant immune population at the tumor interface [12].

Advanced Spatial Transcriptomics Technologies

Multiple technological approaches have been developed for spatial transcriptomics analysis, each with distinct advantages and limitations:

Table 3: Spatial Transcriptomics Technology Platforms

| Technology Type | Representative Methods | Resolution | Throughput | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial Indexing-Based | Visium HD, DBiT-seq | Single-cell scale | High | Pan-tissue mapping, archival samples |

| In Situ Imaging-Based | MERFISH, seqFISH+, Xenium | Subcellular | Medium-high | Targeted high-plex validation, protein co-detection |

| In Situ Sequencing-Based | STARmap, FISSEQ | Cellular | Medium | 3D tissue reconstruction, novel transcript discovery |

| Laser Capture Microdissection | LCM-seq, GEO-seq | Regional | Low-medium | Region-specific profiling, rare cell populations |

The choice of technology depends on specific research questions, with spatial barcoding approaches (like Visium HD) providing unbiased whole transcriptome data, while in situ methods (like Xenium) offer higher resolution for validation studies [12] [10].

Key Signaling Pathways and Cellular Interactions

Macrophage-Tumor Cell Crosstalk in the Tumor Border

Spatial transcriptomic analyses of colorectal cancer have revealed specialized macrophage subpopulations with distinct spatial localizations and functional roles:

These specialized macrophage populations create distinct spatial niches within the TME through different communication mechanisms. SELENOP+ macrophages localize with tumor cells expressing REG family genes (associated with metastasis and poor prognosis) and influence both tumor cells and T cells through pro-tumor metabolic pathways and immune stimulation [12]. Meanwhile, SPP1+ macrophages co-localize with TGFBI+ tumor cells (also linked to poor outcomes) and interact with both tumor and T cells through the CD44 receptor, a known player in tumor initiation and progression [12].

Tertiary Lymphoid Structure Formation and Maturation

Recent pan-cancer analyses of tumor-associated tertiary lymphoid structures (TA-TLS) have revealed conserved cellular dynamics and spatial organization:

Spatial transcriptomic profiling has identified CCL19+ perivascular cells as potential lymphoid tissue organizer (LTo) cells associated with TA-TLS formation [13]. Additionally, arterial endothelial cells within TA-TLS can acquire high endothelial venule (HEV)-like phenotypes in response to Notch signaling inhibition, enhancing immune cell recruitment capacity [13]. Mature TLSs show preferential enrichment of IgG+ plasma cells, highlighting the functional specialization of these structures during maturation [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Spatial Transcriptomics

| Reagent/Platform | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Visium HD Spatial Gene Expression | Whole transcriptome spatial mapping | Unbiased discovery of spatial architecture across entire tissue sections |

| Xenium In Situ Gene Expression | Targeted, subcellular resolution spatial analysis | Validation and deep phenotyping of specific cell types and interactions |

| Flex Gene Expression with Feature Barcoding | Single-cell RNA sequencing reference generation | Creation of cell-type atlas for spatial data deconvolution |

| LIANA Cell-Cell Communication Tool | Ligand-receptor interaction inference from spatial data | Mapping signaling networks between architecturally defined cell populations |

| Universal 5' Gene Expression with MULTI-seq | Multiplexed single-cell profiling | Sample multiplexing for cohort studies and experimental replication |

| Cell Type-Specific Marker Panels | Identification of specialized subpopulations | Classification of macrophage states (e.g., SELENOP+, SPP1+) and other subtypes |

These integrated tools enable comprehensive spatial dissection of the TME, from whole-transcriptome discovery to targeted validation of specific cellular interactions and signaling pathways [12].

Clinical Translation and Therapeutic Applications

Predictive Biomarker Discovery

Spatial transcriptomics has identified clinically relevant biomarkers that predict survival and therapy response:

- Leading Edge Gene Signature: Associated with worse clinical outcomes across multiple cancer types, serving as a potential prognostic biomarker [11]

- B-cell Activity in Tumor-Adjacent Regions: Identified as a biomarker for positive response to neoadjuvant cabozantinib and nivolumab in liver cancer [12]

- SPP1+ Macrophage Infiltration: Associated with poor prognosis in colorectal cancer and potentially predictive of resistance to certain therapies [12]

- TA-TLS Maturation State: Correlates with improved immune activation and clinical outcomes, potentially guiding immunotherapy selection [13]

In Silico Drug Response Modeling

Spatial transcriptomic data enables computational modeling of therapy response through:

- Architectural Drug Mapping: Correlation of spatial gene expression patterns with known drug targets

- Pathway Activity Inference: Assessment of signaling pathway activation in specific spatial niches

- Resistance Mechanism Identification: Revelation of spatially-distributed compensatory pathways that may limit therapeutic efficacy [11]

These approaches have demonstrated predictable associations between spatial transcriptomic patterns and drug response, highlighting the potential for spatial architecture to inform treatment selection and combination strategies [11].

Spatial transcriptomics has fundamentally advanced our understanding of tumor architecture by revealing the functional specialization of distinct tumor regions and the conserved principles of spatial organization across cancer types. The technology provides unprecedented insights into how the three-dimensional arrangement of cells within the TME influences disease progression, therapeutic response, and clinical outcomes.

Future developments in spatial transcriptomics will likely focus on increasing resolution and multiplexing capacity, improving computational integration of multi-omic datasets, and enhancing accessibility for clinical translation. As these technologies mature, spatial architecture assessment may become a standard component of cancer diagnostics and therapeutic decision-making, ultimately enabling more precise and effective targeting of the complex ecological systems within tumors.

The journey to understand the transcriptome has driven the evolution of sequencing technologies from bulk analysis to single-cell resolution and now to spatially contextualized measurement. This progression has been particularly transformative in oncology, where the complex cellular ecosystem of the tumor microenvironment (TME) plays a critical role in cancer progression, therapeutic resistance, and patient outcomes [14] [15]. Bulk RNA sequencing provided the first comprehensive tools for gene expression analysis but averaged signals across diverse cell populations, masking critical heterogeneity. Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) resolved this by profiling individual cells, revealing rare populations and transcriptional diversity previously obscured in bulk measurements [14]. The latest frontier, spatial transcriptomics (ST), now preserves the architectural context of gene expression, enabling researchers to map molecular activity within intact tissue structure and visualize cellular interactions that define tumor biology [15] [16].

The integration of these technologies provides a powerful, multi-dimensional approach to dissecting the TME. While scRNA-seq identifies cellular constituents and their states, ST maps these populations within the tissue landscape, revealing how spatial organization and neighborhood relationships influence cancer behavior and treatment response [15]. This evolution from bulk to single-cell to spatial analysis represents a paradigm shift in precision oncology, enabling unprecedented investigation into tumor heterogeneity, immune evasion mechanisms, and stromal interactions [16].

Technological Evolution and Platform Comparisons

From Bulk to Single-Cell Resolution

Bulk RNAseq processes tissue or cell populations as a mixture, generating an average gene expression profile that has been invaluable for cancer classification, biomarker discovery, and identifying differentially expressed genes [14]. However, its fundamental limitation lies in masking the heterogeneity inherent to tumors, which contain diverse malignant, immune, and stromal components [14] [17]. This averaging effect obscures rare but biologically critical cell populations, such as drug-resistant clones or immune cell subsets that modulate therapeutic response.

The development of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq), particularly high-throughput platforms like 10X Genomics Chromium, enabled parallel analysis of up to 20,000 individual cells [14]. By partitioning single cells into nanoliter-scale droplets containing barcoded beads, scRNA-seq assigns a unique cellular identifier to each transcript, allowing computational reconstruction of individual cell expression profiles [14]. This resolution has revealed extraordinary heterogeneity within tumors, identifying rare stem-like populations with treatment-resistant properties, distinct cellular states along differentiation trajectories, and minority cell populations that drive cancer progression [14].

Spatial Transcriptomics Platforms and Performance

Spatial transcriptomics technologies have rapidly advanced, branching into two primary methodological categories: sequencing-based (sST) and imaging-based (iST) platforms [18] [19]. Each offers distinct advantages and trade-offs in resolution, sensitivity, and transcriptome coverage.

Table 1: Comparison of High-Throughput Spatial Transcriptomics Platforms

| Platform | Company | Methodology | Resolution | Targets | Sample Types | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xenium | 10x Genomics | Padlock probes with rolling circle amplification | Subcellular | 5,000 RNAs | FFPE, Fresh Frozen | Tumor heterogeneity, cellular interactions |

| CosMx | NanoString | Branched DNA probes with multiple readout sequences | Subcellular | 6,000 RNAs (6K panel) | FFPE, Fresh Frozen | Cell typing, tumor-immune interactions |

| MERSCOPE | Vizgen | Multiple probes per RNA with unique readout sequences | Subcellular | 1,000 RNAs | FFPE, Fresh Frozen | Targeted panel analysis, spatial mapping |

| Visium HD | 10x Genomics | Spatially barcoded spots for mRNA capture | 2 μm | All poly-A RNA (18,085 genes) | FFPE, Fresh Frozen | Whole transcriptome, discovery research |

| Stereo-seq | BGI Genomics | DNA nanoball arrays for RNA capture | 500 nm | All poly-A RNA | Fresh Frozen (FFPE possible) | High-resolution mapping, developmental biology |

Recent systematic benchmarking studies have evaluated these platforms across multiple cancer types, including colon adenocarcinoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, and ovarian cancer [18]. Performance assessments reveal that Xenium consistently generates higher transcript counts per gene without sacrificing specificity, while both Xenium and CosMx measure RNA transcripts in concordance with orthogonal single-cell transcriptomics data [19]. For whole transcriptome analysis, Visium HD and Stereo-seq provide unbiased detection, with Stereo-seq offering superior spatial resolution (500 nm) [18].

Table 2: Performance Metrics from Spatial Transcriptomics Benchmarking Studies

| Platform | Sensitivity | Specificity | Concordance with scRNA-seq | Cell Segmentation Accuracy | Transcript Diffusion Control |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xenium | High | High | High | Moderate to High | Excellent |

| CosMx | Moderate | High | High | Moderate | Good |

| MERSCOPE | Moderate | High | Moderate | Moderate | Good |

| Visium HD | High | High | High | N/A (spot-based) | Moderate |

| Stereo-seq | High | High | High | N/A (bin-based) | Moderate |

Experimental Protocols for Spatial Transcriptomics in TME Characterization

Sample Preparation and Platform Selection

Sample Considerations and Pre-processing

- Tissue Collection: Obtain fresh tumor specimens via surgical resection or biopsy, minimizing ischemia time (≤30 minutes) to preserve RNA integrity [18] [19].

- Preservation Methods: Either flash-freeze in optimal cutting temperature (OCT) compound for cryosectioning or fix in 10% neutral buffered formalin (16-24 hours) followed by standard paraffin embedding (FFPE) [19].

- Sectioning: Cut serial sections at 5-10 μm thickness using a microtome (FFPE) or cryostat (frozen). Mount sections on specially coated slides provided by platform manufacturers [18].

- Quality Control: Assess RNA integrity (DV200 > 60% recommended for FFPE), review H&E staining for morphological preservation, and confirm tumor content >70% for enriched analysis [19].

Platform Selection Guidelines

- For hypothesis-driven studies with predefined gene panels (e.g., immune oncology, pathway analysis), select targeted iST platforms (Xenium, CosMx, MERSCOPE) [19].

- For discovery research requiring whole transcriptome coverage, choose sST platforms (Visium HD, Stereo-seq) [18].

- When working with precious archival samples, prioritize FFPE-compatible platforms (Xenium, CosMx, MERSCOPE) validated for degraded RNA [19].

- For high-resolution single-cell mapping with large gene panels, consider Xenium (5,000 genes) or CosMx (6,000 genes) [18].

Workflow for Integrated Single-Cell and Spatial Analysis

The following diagram illustrates a comprehensive workflow that integrates single-cell and spatial transcriptomics to characterize the tumor microenvironment:

Data Processing and Analytical Framework

Primary Data Processing

- Image Processing: Align fluorescence images (iST) or brightfield images (sST) with transcript detection coordinates [20] [21].

- Cell Segmentation: Generate cell boundaries using DAPI nuclear staining (all platforms) with optional membrane markers (Xenium, CosMx). Tools include Cellpose, Baysor, or platform-specific algorithms [21] [19].

- Transcript Assignment: Map detected transcripts to segmented cells using probabilistic models that account for cell boundaries and transcript proximity [20].

Cell Type Annotation and Spatial Analysis

- Reference-Based Annotation: Utilize scRNA-seq data from matched samples as reference for cell type transfer using methods like RCTD, SingleR, or Azimuth [21].

- Spatial Clustering: Identify spatially coherent domains using algorithms such as SpaGCN, BayesSpace, or STAGATE that incorporate spatial neighborhood information [21] [22].

- Cell-Cell Interaction Analysis: Infer ligand-receptor interactions and communication patterns with tools like CellChat, COMMOT, or NICHES that leverage spatial proximity [21].

Signaling Pathways in the Tumor Microenvironment

The tumor microenvironment comprises multiple cell types engaging in complex signaling networks that drive cancer progression. The following diagram illustrates key pathways and cellular interactions within the TME:

Spatial transcriptomics has been particularly valuable in mapping the distribution and activity of these pathways within tumor tissues. For example, the PD-1/PD-L1 immune checkpoint pathway shows distinct spatial patterns at the tumor-immune interface, with PD-L1 expression often highest in cancer cells bordering T cell-infiltrated regions [15]. The VEGF signaling pathway drives angiogenesis and is typically elevated in hypoxic regions distant from functional vasculature [15]. TGF-β signaling is frequently activated at the invasive margin where cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) remodel the extracellular matrix (ECM) to facilitate cancer cell invasion [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Successful implementation of spatial transcriptomics requires both wet-lab reagents and computational tools for data analysis and interpretation.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Spatial Transcriptomics

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Expression Panels | Xenium Multi-Tissue Panel, CosMx 6K Human Panel, MERSCOPE Custom Panels | Targeted transcript detection | Select panels covering cell type markers, signaling pathways of interest |

| Sample Preparation Kits | 10x Genomics Visium HD Gene Expression Kit, NanoString CosMx Sample Preparation Kit | Tissue processing, library preparation | Platform-specific optimized protocols |

| Nuclear & Membrane Stains | DAPI, CellMask Membrane Stains, Alexa Fluor-conjugated antibodies | Cell segmentation, morphology assessment | Critical for accurate cell boundary definition |

| Signal Amplification Reagents | Rolling Circle Amplification (RCA) reagents, Branch Chain Amplification reagents | Signal enhancement for detection | Platform-specific chemistry requirements |

| Immune Cell Markers | CD45, CD3, CD20, CD68, CD163 | Immune cell population identification | Essential for TME characterization |

Table 4: Computational Tools for Spatial Transcriptomics Data Analysis

| Tool Category | Software/Tool | Function | Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Processing | Space Ranger (10x), Xenium Analyzer, CosMx Data Processing | Primary data analysis, decoding | Platform-specific primary analysis |

| Cell Segmentation | Baysor, Cellpose, StarDist, Mesmer | Cell boundary detection | Critical for single-cell resolution |

| Cell Type Annotation | RCTD, SingleR, Azimuth, CellTypist | Reference-based cell typing | Leverages scRNA-seq references |

| Spatial Analysis | Squidpy, Giotto, SpaciAlign, STalign | Neighborhood analysis, spatial domains | Identifies spatial patterns |

| Cell-Cell Communication | CellChat, COMMOT, NICHES | Interaction inference | Predicts signaling networks |

| Multi-Slice Integration | PASTE, STalign, SPACEL | 3D reconstruction, alignment | Aligns serial sections |

The evolution from bulk to single-cell to spatial transcriptomics represents a fundamental transformation in how researchers investigate biological systems, particularly in complex environments like the tumor microenvironment. Each technological advancement has addressed limitations of its predecessor while introducing new capabilities: bulk RNAseq provided comprehensive transcriptome coverage but masked cellular heterogeneity; scRNA-seq revealed cellular diversity but lost spatial context; and now spatial transcriptomics preserves architectural relationships while capturing molecular information at increasingly high resolution.

The integration of these approaches enables a comprehensive understanding of tumor biology that incorporates both cellular composition and spatial organization. As spatial technologies continue to advance—with improvements in resolution, sensitivity, and throughput—they promise to uncover novel therapeutic targets, illuminate mechanisms of treatment resistance, and ultimately guide more effective personalized cancer therapies. For researchers embarking on spatial transcriptomics studies, the key considerations include careful platform selection based on research questions, implementation of robust analytical pipelines, and integration with complementary single-cell and bulk datasets to maximize biological insights.

The spatial organization of the tumor microenvironment (TME) is a critical determinant of cancer progression, therapeutic response, and patient prognosis. Technological advances in spatial transcriptomics (ST) have enabled researchers to move beyond simple cellular inventories to mapping the intricate architectural patterns within tumors. These studies consistently reveal two distinct yet interconnected geographical regions: the tumor core (TC) and the leading edge (LE). The TC represents the central region of the tumor mass, while the LE comprises the invasive border where tumor cells interact with surrounding host tissue. Understanding the unique biological features of these compartments provides valuable insights into tumor behavior and unveils new opportunities for therapeutic intervention. This document outlines the key differences between these regions and provides detailed experimental protocols for their characterization.

Biological Distinctions Between Tumor Core and Leading Edge

Integrative single-cell and spatial transcriptomic analyses of HPV-negative oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) and other cancers have delineated fundamental biological differences between the TC and LE, summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Key Comparative Features of Tumor Core and Leading Edge

| Feature | Tumor Core (TC) | Leading Edge (LE) |

|---|---|---|

| Transcriptional Profile | Epithelial differentiation program; Keratinization (e.g., SPRR genes) [23] [24] | Partial epithelial-mesenchymal transition (p-EMT); Extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling (e.g., COL1A1, FN1) [23] [24] |

| Hallmark Pathways | Keratinization, cell differentiation, antimicrobial immunity [23] | Cell cycle, EMT, angiogenesis, protein translation [23] |

| Cellular Neighborhood | Mixed immune-stromal composition; Detox-iCAFs [23] | Enriched with ECM-myCAFs; Immunosuppressive cells (Tregs, M2 TAMs) [23] [25] |

| Prognostic Association | Gene signature associated with improved prognosis across multiple cancers [23] [24] | Gene signature associated with worse clinical outcomes and invasion across multiple cancers [23] [24] |

| Pan-Cancer Conservation | Tissue-specific transcriptional programs[c:1][c:5] | Conserved transcriptional programs across different cancer types[c:1][c:5] |

The cellular neighborhoods and interaction patterns further define the functionality of these regions. The LE of Head and Neck SCC (HNSCC) is often dominated by immunosuppressive cells like regulatory T cells (Tregs) and M2-polarized tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), which facilitate immune evasion. In contrast, CD8+ cytotoxic T cells are more frequently found at the invasion front, adjacent to the LE [25]. Cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) also exhibit spatial functional heterogeneity; ecm-myCAFs, which promote ECM remodeling and invasion, are often enriched at the LE, while other subtypes like detox-iCAFs may be found in the core [23].

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Spatial Analysis

The following protocols describe key methodologies for characterizing the TC and LE using spatial transcriptomics.

Protocol: Spatial Transcriptomics Profiling and Cellular Deconvolution

This protocol is adapted from the analysis of 12 fresh-frozen OSCC samples using the 10x Genomics Visium platform [23] [24].

- Objective: To generate spatially resolved gene expression data and identify the cellular composition of distinct tumor regions.

- Materials:

- Fresh-frozen tumor tissue sections (typically 10 µm thickness)

- 10x Genomics Visium Spatial Gene Expression Slide & Reagents

- Histological staining reagents (H&E)

- Standard NGS library preparation and sequencing reagents

- Publicly available matched scRNA-seq dataset for the cancer type (e.g., HNSCC)

- Procedure:

- Tissue Preparation & Sequencing: Follow the manufacturer's protocol for tissue mounting, permeabilization, cDNA synthesis, and library construction. Sequence the libraries to a target of approximately 40,000-50,000 reads per spot.

- Pathologist Annotation: A pathologist examines H&E-stained images from each sample to morphologically annotate regions of interest, including suspected TC and LE.

- Data Preprocessing: Perform normalization, batch effect correction, and dimensionality reduction on the ST data using standard tools (e.g., Seurat).

- Malignant Spot Identification: Use integrative analysis with a scRNA-seq reference to deconvolve cell types.

- Calculate a deconvolution score; spots with a score >0.99 for malignant cells are classified as malignant.

- Perform copy number variation (CNV) inference; spots with a CNV probability score >0.99 are classified as malignant.

- Cellular Annotation: Annotate non-malignant spots (e.g., immune cells, CAFs) using marker genes from the scRNA-seq dataset (e.g., LRRC15 for ecm-myCAFs, ADH1B for detox-iCAFs).

Protocol: Unsupervised Clustering for Spatial Domain Identification

This protocol details the process of defining TC and LE based on transcriptional profiles [23] [24].

- Objective: To identify spatially coherent transcriptional clusters within the malignant cell population.

- Input: The matrix of malignant spots identified in Protocol 3.1.

- Procedure:

- Clustering: Perform unsupervised Louvain clustering on the aggregated malignant spots based on their gene expression profiles.

- Differential Gene Expression (DGE): For each resulting cluster, perform DGE analysis to identify significantly upregulated marker genes.

- Spatial Annotation:

- Annotate clusters enriched with TC markers (e.g., CLDN4, SPRR1B, keratinization genes) as "Tumor Core."

- Annotate clusters enriched with LE markers (e.g., LAMC2, ITGA5, ECM genes, p-EMT program genes) as "Leading Edge."

- A "Transitory" cluster may be identified, expressing a hybrid signature.

- Validation: Generate a correlation matrix of whole transcriptome profiles from annotated TC and LE regions across patients. A high intra-region and low inter-region correlation validates distinct and conserved architectures.

Protocol: Analysis of Ligand-Receptor Interactions and Cell Communication

- Objective: To identify spatially regulated cell-cell communication networks.

- Input: Spatially annotated ST data and cell-type deconvolution results.

- Procedure:

- Spatial Neighborhood Definition: Define cellular neighborhoods based on the physical proximity of spots of different cell types.

- Interaction Scoring: Use a tool like CellPhoneDB or a spatial interaction method to analyze co-localization and potential ligand-receptor interactions.

- Index Calculation: For multiplex immunohistochemistry (mIHC) data, an interaction index can be calculated. Define interacting cells as those with a Euclidean distance <100 pixels (approx. 22 µm) from each other. Normalize the number of interactions to the abundance of the corresponding cell types in each sample [26].

Signaling Pathways and Therapeutic Implications

The distinct transcriptional profiles of the TC and LE are driven by the activation of specific signaling pathways, which reveal potential therapeutic vulnerabilities. Key pathways are visualized below.

Diagram: Activated signaling pathways in the tumor core and leading edge. Pathways enriched in the LE are frequently associated with invasion and poor prognosis, while TC pathways are often linked to improved outcomes [23].

The LE is characterized by pathways that drive invasion, metastasis, and proliferation. These include the p-EMT program, angiogenesis, and specific signaling pathways such as EIF2, GP6, and HOTAIR [23]. In contrast, the TC exhibits pathways related to epithelial differentiation, keratinization, and distinct immune signaling, including IL-33 and p38 MAPK pathways [23]. The LE gene signature is a conserved marker of aggressiveness across multiple cancer types, while the TC signature is often more tissue-specific and associated with better survival [23] [24].

From a therapeutic perspective, targeting the conserved, aggressive nature of the LE is a promising strategy. In silico modeling based on these spatial transcriptomic patterns can identify drugs that disrupt the pathogenic information flow from the TC to the LE [23] [24]. Furthermore, the dense, immunosuppressive microenvironment at the LE may explain the failure of immunotherapies in some cases, as cytotoxic T cells are often excluded from this region [25]. This highlights the need for combination therapies that simultaneously target the cancer cells and remodel the immunosuppressive LE neighborhood.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful spatial characterization of the TME relies on a suite of specialized reagents and computational tools.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Spatial Transcriptomics

| Category | Item/Solution | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Wet-Lab Reagents | 10x Genomics Visium Spatial Kit | Captures whole transcriptome data while preserving spatial location on a tissue section [23]. |

| Fresh-frozen tissue sections (OCT-embedded) | Preserves RNA integrity for high-quality spatial gene expression profiling [23]. | |

| H&E Staining Reagents | Provides histological context for pathologist annotation of tumor regions [23] [27]. | |

| Multiplex Immunohistochemistry (mIHC) Panels | Validates and quantifies specific immune and stromal cell populations in situ (e.g., T cells, macrophages) [26]. | |

| Computational Tools | Spatial Clustering (e.g., STAGATE, SpaGCN, STAIG) | Identifies spatial domains by integrating gene expression and spatial location data [28] [27] [23]. |

| Multi-Slice Integration (e.g., spCLUE, GRASS) | Integrates and aligns multiple ST tissue slices, removing batch effects for unified analysis [28] [29]. | |

| Cell-Cell Interaction Analysis (e.g., CellPhoneDB) | Infers potential ligand-receptor interactions from spatial co-localization data [26]. | |

| CNV Inference Tools (e.g., InferCNV) | Distinguishes malignant cells from non-malignant cells based on copy number alterations [23]. |

Spatial Heterogeneity as a Driver of Treatment Resistance and Metastasis

Spatial heterogeneity, the variation in the genetic, epigenetic, and phenotypic composition of cancer cells and their microenvironment across different physical locations within a tumor, is a fundamental driver of treatment failure and metastatic progression. This heterogeneity manifests not only between different tumors in the same patient (inter-tumor heterogeneity) but also within individual tumor masses (intra-tumor heterogeneity) [30] [31]. The complex spatial architecture of tumors creates distinct ecological niches that shape evolutionary dynamics, fostering the emergence of resistant clones and enabling metastatic dissemination. Spatial transcriptomics has emerged as a revolutionary tool for characterizing this heterogeneity, allowing researchers to preserve the geographical context of gene expression patterns within intact tumor tissues [32] [33]. Unlike traditional bulk sequencing methods that homogenize tissues, or even single-cell RNA sequencing that requires tissue dissociation and loses spatial information, spatial transcriptomics provides a comprehensive map of cellular interactions, regional adaptations, and microenvironmental influences that drive oncogenesis [33].

The clinical implications of spatial heterogeneity are profound. It compromises treatment efficacy by creating sanctuary sites where drug-resistant subpopulations can evade therapy, and it drives metastatic progression by selecting for invasive phenotypes adapted to survive in foreign microenvironments [34] [31]. Understanding and quantifying this spatial complexity is therefore essential for developing more effective, personalized cancer therapies that can anticipate and overcome resistance mechanisms. This application note explores the mechanisms through which spatial heterogeneity drives treatment resistance and metastasis, details experimental protocols for its characterization, and provides resources for integrating spatial biology into drug development pipelines.

Mechanisms Linking Spatial Heterogeneity to Treatment Resistance

Genetic and Clonal Heterogeneity

Tumor evolution is characterized by the accumulation of genetic alterations that create diverse subclonal populations spatially segregated within tumors. Multi-regional sequencing studies have demonstrated substantial spatial heterogeneity in genetic composition, not only between distinct anatomical locations but also in different regions within the same tumor [35]. This genetic diversity provides the raw material for selection pressures, including therapeutic interventions, to act upon. In prostate cancer, for instance, which is often multifocal, different tumor foci can exhibit independent clonal expansions, with individual foci showing remarkably different mutation profiles and copy number alterations [30]. This clonal complexity means that therapies targeting specific genetic alterations may effectively eliminate sensitive clones while leaving resistant subpopulations untouched, ultimately leading to disease recurrence.

The Tumor Microenvironment as a Sanctuary Site

The tumor microenvironment (TME) comprises non-malignant cells including cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), immune cells, endothelial cells, and extracellular matrix components that interact with cancer cells to influence treatment response. Spatial heterogeneity within the TME creates sanctuary sites—physical locations where cancer cells are protected from therapeutic assault due to limited drug penetration or the presence of survival factors [34]. Mathematical modeling of drug distribution patterns has demonstrated that resistant mutants are most likely to emerge initially in these sanctuary compartments with poor drug penetration, subsequently migrating to and repopulating regions with higher drug concentrations [34].

Cancer-associated fibroblasts exhibit remarkable functional heterogeneity within the TME. Single-cell RNA sequencing has identified at least six distinct subpopulations of CAFs in human prostate cancer, each secreting different cytokines with variable immunomodulatory properties [30]. For instance, CAFs expressing CCL2 aid in recruiting myeloid cells to the TME, correlating with poor clinical outcomes, while CXCL12-expressing CAFs recruit mast cells, eosinophils, and T helper 2 cells that promote tumor growth [30]. This spatial organization of CAF subpopulations creates microenvironments with differing capacities to support cancer cell survival under therapeutic pressure.

Metabolic and Hypoxic Gradients

Spatial heterogeneity in resource availability represents another critical driver of treatment resistance. Tumors frequently develop aberrant vascular networks that result in heterogeneous oxygen and nutrient distribution [30]. Regions distal to blood vessels experience hypoxia, which activates hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) signaling pathways that promote treatment resistance through multiple mechanisms, including reduced drug uptake, altered cell cycle progression, and enhanced DNA repair capacity [30]. In prostate cancer, measurements using oxygen electrodes have revealed that oxygen status changes across tumor foci and even within the same tumor, creating spatially distinct selective pressures that shape tumor evolution [30]. Hypoxic cells survive the hostile growth conditions, and through HIF signaling, can undergo epithelial-mesenchymal transition and neuroendocrine transdifferentiation, further contributing to heterogeneity and therapeutic resistance [30].

Table 1: Mechanisms of Spatial Heterogeneity-Driven Treatment Resistance

| Mechanism | Key Features | Impact on Treatment |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic Heterogeneity | Spatially segregated subclones with distinct mutation profiles; branching evolution patterns | Targeted therapies eliminate sensitive clones but select for pre-existing resistant subpopulations |

| Microenvironmental Sanctuary Sites | Limited drug penetration; CAF-mediated protection; physical barriers | Creates protected niches where cancer cells survive treatment and initiate recurrence |

| Metabolic Gradients | Hypoxic regions; acidic pH; nutrient deprivation | Activates survival pathways, reduces drug efficacy, and promotes resistant phenotypes |

| Stromal Interactions | Heterogeneous CAF subpopulations; immune cell exclusion; matrix remodeling | Direct protection through survival factors; physical barrier to drug delivery |

Spatial Heterogeneity in Metastatic Progression

Clonal Origins of Metastasis

Metastasis represents the ultimate manifestation of spatial heterogeneity, with disseminated tumor cells adapting to thrive in diverse tissue environments. The clonal origins of metastases can be traced back to specific subpopulations within the primary tumor that have acquired the necessary mutations and phenotypic plasticity to complete the metastatic cascade. Studies in prostate cancer have revealed that metastases can be monoclonal in origin, with identical copy number changes observed in disseminated cells [30], though polyclonal dissemination has also been documented. The spatial position of these metastatic-competent subclones within the primary tumor influences their access to vascular and lymphatic channels, thereby affecting their dissemination potential.

Microenvironment of Metastatic Niches

The successful establishment of metastases depends critically on the creation of a supportive microenvironment at secondary sites—the "metastatic niche." Spatial transcriptomic analyses have revealed that metastatic cells reprogram the local stroma at secondary sites to create favorable conditions for their survival and growth. In advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), for example, scRNA-seq analyses of primary tumors, lymph node metastases, and normal lung tissue have demonstrated that the multicellular ecosystem of metastatic sites exhibits distinct features, including altered immune cell compositions and stromal cell phenotypes [31]. Specifically, endothelial cells in metastatic sites show greater similarity to those in primary tumors than to normal endothelium, suggesting early reprogramming of the vascular niche to support metastatic growth [31].

Ecological Dynamics of Metastatic Colonization

The process of metastatic colonization follows ecological principles, with disseminated tumor cells competing with resident cells for resources and space. Spatial heterogeneity in the tissue architecture of secondary organs creates variation in the fitness landscapes that metastatic cells must navigate. Agent-based modeling approaches have demonstrated that the spatial distribution of resistant cells and fibroblasts significantly influences treatment outcomes across metastatic lesions [36]. Virtual patients with multiple metastatic sites composed of different spatial distributions of fibroblasts and drug-resistant cell populations show markedly different responses to therapy, highlighting the importance of accounting for spatial heterogeneity across all disease sites when designing treatment strategies [36].

Table 2: Spatial Transcriptomics Platforms for Characterizing Tumor Heterogeneity

| Platform | Technology Type | Resolution | Multiplex Capacity | Best Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10X Visium | In situ capturing (ISC) | 55 μm spots | Whole transcriptome | Unbiased discovery; tumor microenvironment mapping |

| Slide-seq | In situ capturing (ISC) | 10 μm spots | Whole transcriptome | Higher resolution mapping; cell-type localization |

| MERFISH | In situ hybridization (ISH) | Subcellular | 500-10,000 genes | High-efficiency transcript detection; subcellular localization |

| SeqFISH+ | In situ hybridization (ISH) | Subcellular | Up to 10,000 genes | Targeted high-plex imaging; spatial mapping of gene networks |

| STARmap | In situ sequencing (ISS) | Subcellular | Up to 1,000 genes | 3D localization; targeted pathway analysis |

Experimental Protocols for Spatial Heterogeneity Analysis

Spatial Transcriptomics Workflow Using 10X Visium

Principle: This protocol uses a slide-based array with spatially barcoded oligonucleotides to capture mRNA molecules from intact tissue sections, enabling correlation of gene expression data with histological features [32] [33].

Protocol Steps:

- Tissue Preparation: Fresh frozen or OCT-embedded tissues are cryosectioned at 5-10 μm thickness and mounted onto Visium slides. Optimal cutting temperature (OCT) compound should be carefully applied to avoid bubbles.

- Fixation and Staining: Sections are fixed in pre-chilled methanol (-20°C) for 30 minutes, followed by histological staining (H&E or others) and high-resolution brightfield imaging to document tissue morphology.

- Permeabilization: Tissue sections are treated with permeabilization enzyme for optimized duration (typically 12-24 minutes) to allow mRNA diffusion and capture. Permeabilization time must be determined empirically for each tissue type.

- cDNA Synthesis: Captured mRNAs are reverse-transcribed directly on the slide using barcoded primers. The spatial barcodes incorporated during this step preserve positional information.

- Library Preparation: cDNA is harvested from the slide and converted to sequencing libraries with Illumina adapters and sample indices using a proprietary Visium library construction kit.

- Sequencing and Analysis: Libraries are sequenced on Illumina platforms (recommended depth: 50,000 read pairs per spot). Data analysis involves alignment to a reference genome, spatial barcode processing, and integration with histological images.

Troubleshooting Tips:

- Incomplete permeabilization results in low mRNA capture; over-permeabilization causes diffusion of spatial signals.

- OCT contamination inhibits cDNA synthesis; ensure complete removal before proceeding to library prep.

- For fibrous tissues (e.g., breast cancer), extend permeabilization time by 30-50% and verify with RNA quality control metrics.

Multiplexed RNA Imaging with MERFISH

Principle: Multiplexed error-robust fluorescence in situ hybridization (MERFISH) uses combinatorial barcoding and sequential hybridization with fluorescent probes to detect hundreds to thousands of RNA species simultaneously in their native spatial context [32].

Protocol Steps:

- Probe Design: Design encoding probes targeting genes of interest using a combinatorial barcoding scheme with error-correction properties.

- Sample Preparation: Cells or tissue sections are fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 15 minutes and permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 for 10 minutes.

- Hybridization: Samples are incubated with the pooled encoding probe set in hybridization buffer (30% formamide, 2× SSC) at 37°C for 36-48 hours.

- Sequential Imaging: Perform multiple rounds of hybridization, imaging, and probe stripping. Each round uses fluorescently labeled readout probes that bind to specific positions in the encoding probes.

- Image Processing and Decoding: Computational algorithms decode the combinatorial fluorescence signals from all imaging rounds into digital RNA counts for each gene at subcellular locations.

Applications in Drug Resistance: MERFISH can map the spatial distribution of drug resistance markers (e.g., ABC transporters), stress response genes, and proliferation markers within the context of tissue architecture, revealing how resistant subclones are organized relative to protective microenvironmental elements.

Integrated Single-Cell and Spatial Transcriptomics

Principle: This integrated approach combines the high-resolution cell-type identification of scRNA-seq with spatial context from spatial transcriptomics to comprehensively map cellular ecosystems in tumors [33].

Protocol Steps:

- Parallel Processing: Process adjacent sections from the same tumor block using both scRNA-seq (after tissue dissociation) and spatial transcriptomics platforms.

- Cell Type Annotation: Cluster scRNA-seq data to identify distinct cell populations and define marker gene signatures for each cluster.

- Spatial Mapping: Use computational methods (e.g., Seurat integration, cell2location) to map the cell types identified in scRNA-seq onto the spatial transcriptomics data.

- Niche Identification: Identify recurrent spatial neighborhoods or niches characterized by specific cell-type combinations.

- Cross-Validation: Validate spatial mapping results using multiplexed protein imaging (e.g., CODEX, CyCIF) for key markers.

Data Integration Challenges:

- Batch effects between dissociated and intact tissue samples must be corrected using robust normalization methods.

- Differences in resolution between single-cell and spot-based data require specialized statistical approaches for confident mapping.

Signaling Pathways in Spatial Heterogeneity

The following diagrams illustrate key signaling pathways that drive spatial heterogeneity in the tumor microenvironment, created using DOT language with specified color palette.

Diagram 1: Hypoxia-Driven Heterogeneity Pathway. Hypoxic conditions stabilize HIF-1α, driving multiple processes that promote spatial heterogeneity and treatment resistance [30].

Diagram 2: CAF Heterogeneity and Signaling. Multiple cellular sources give rise to heterogeneous CAF populations that promote therapy resistance through diverse signaling mechanisms [30].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Spatial Heterogeneity Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Spatial Transcriptomics Platforms | 10X Genomics Visium HD, NanoString GeoMx, Lunaphore COMET | High-plex RNA and protein spatial profiling; Visium HD provides high-resolution gene expression; GeoMx offers precise segmentation; COMET enables subcellular imaging |

| Tissue Preservation Media | RNAlater, Optimal Cutting Temperature (OCT) compound | Preserve RNA integrity and tissue architecture during storage and sectioning |

| Permeabilization Reagents | Protease (from 10X Visium kit), Triton X-100, SDS | Controlled tissue permeabilization to enable probe access while maintaining spatial information |

| Multiplexed FISH Probes | MERFISH encoding probes, SeqFISH+ probes, ViewRNA assays | Highly multiplexed RNA detection in situ with single-molecule sensitivity |

| Library Preparation Kits | Visium Spatial Gene Expression reagent kit, SMART-Seq v4 | Convert spatially barcoded RNA to sequencing libraries; maintain spatial barcodes throughout amplification |

| Bioinformatics Tools | Seurat, STutility, Cell2location, Giotto | Process, integrate, and analyze spatial transcriptomics data; map cell types; identify spatial patterns |

Spatial heterogeneity represents a fundamental challenge in oncology that contributes significantly to treatment resistance and metastatic progression. The emergence of spatial transcriptomics and related spatial biology platforms has provided unprecedented insights into the architectural organization of tumors and their microenvironments, revealing how the physical distribution of cellular subtypes creates sanctuaries for resistant clones and launching pads for metastatic dissemination. The experimental protocols and resources outlined in this application note provide a roadmap for researchers seeking to integrate spatial analyses into their investigation of tumor heterogeneity.

Looking forward, the integration of spatial multi-omics data into drug development pipelines holds promise for accelerating therapeutic innovation [37] [38]. By identifying spatial biomarkers of resistance and mapping the cellular neighborhoods associated with treatment failure, researchers can design more effective combination therapies that simultaneously target cancer cells and modulate their supportive microenvironments. Furthermore, spatial profiling of metastatic lesions may reveal novel vulnerabilities that could be exploited to prevent or treat disseminated disease. As these technologies become more accessible and scalable, spatial biology is poised to transform cancer research and clinical practice, ultimately delivering on the promise of precision oncology.

Spatial Transcriptomics Technologies and Their Transformative Applications in Oncology

Spatial transcriptomics (ST) has emerged as a revolutionary technology for profiling gene expression while preserving crucial spatial context within tissues, proving particularly valuable for deciphering the complex cellular ecosystem of the tumor microenvironment (TME) [15] [39]. Sequencing-based platforms capture RNA molecules using spatially barcoded oligonucleotides on a surface, followed by high-throughput sequencing to decode the spatial origin of the transcripts [40]. This approach provides untargeted, whole-transcriptome coverage essential for uncovering novel biological insights in cancer research [39].

The table below summarizes the key technical specifications of major sequencing-based spatial transcriptomics platforms.

Table 1: Technical Specifications of Sequencing-Based Spatial Transcriptomics Platforms

| Platform | Resolution (Spot Size) | Tissue Capture Area | Key Applications in TME | Poly(A) Dependence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10x Visium | 55 µm [41] | 6.5 mm × 6.5 mm (standard); 11 mm × 11 mm (extended) [39] | Cellular heterogeneity, immune cell localization [15] | Yes (poly(A) selection) [42] |

| Visium HD | 2 µm (subcellular resolution) [39] | 6.5 mm × 6.5 mm [39] | Single-cell level mapping within TME, rare cell interactions [43] [44] | Yes (poly(A) selection) [42] |

| Slide-seq | 10 µm [41] | Variable (high-density bead array) | Subclone detection, CNA inference, spatial ecology of tumors [41] | Presumed Yes |

| Stereo-seq V2 | Single-cell level [45] | Variable (customizable chip) | Total RNA profiling (including non-poly(A) RNA), immune repertoire, pathogen transcriptomes [45] | No (random priming) [45] |

Each platform offers distinct advantages for TME characterization. Visium HD represents a significant advancement in resolution, enabling "subcellular resolution" for detailed mapping of cellular neighborhoods and stromal-immune interfaces within tumors [44] [39]. Stereo-seq V2 employs a random-priming strategy that provides "unbiased transcript capturing" and "uniform gene body coverage," which is particularly valuable for detecting non-polyadenylated RNAs and profiling the immune repertoire in clinical FFPE samples [45]. Slide-seq offers "near single cellular resolution" (10 µm) that enables computational detection of spatial copy number alterations (CNAs) and tumor subclones when combined with tools like SlideCNA [41].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

10x Visium HD Spatial Gene Expression Workflow

The Visium HD workflow requires meticulous sample preparation and library construction to achieve high-quality spatial data for TME characterization [43] [42].

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for Visium HD Experiments

| Reagent/Kit Name | Specific Function | Application in TME Research |

|---|---|---|

| Visium HD, Human Transcriptome, 6.5 mm, 4/16 rxns (PN-1000675/1000673) | Captures polyadenylated RNA from human tissue sections | Profiling human tumor gene expression signatures |

| Visium HD, Mouse Transcriptome, 6.5 mm, 4/16 rxns (PN-1000676/1000674) | Captures polyadenylated RNA from mouse tissue sections | Studying TME in mouse cancer models |

| Visium CytAssist Reagent Accessory Kit (PN-1000499) | Enables sample analysis on Visium Spatial Gene Expression Slides | Adapting assay for different sample types |

| Dual Index Kit TS Set A, 96 rxns (PN-1000251) | Provides unique dual indices for sample multiplexing | Pooling multiple tumor samples in a single sequencing run |

Sample Preparation Protocol:

- Tissue Preservation and Sectioning: Begin with FFPE, Fresh Frozen, or Fixed Frozen tissue sections [42]. For FFPE samples, ensure optimal fixation (typically 24-72 hours in 10% neutral buffered formalin) followed by standard processing and embedding. For frozen tissues, embed in OCT compound and cryosection at appropriate thickness (typically 5-10 µm).

- Slide Preparation: Use Visium HD Spatial Gene Expression slides. Ensure slides are at room temperature before use. For FFPE sections, perform deparaffinization and H&E or immunofluorescence (IF) staining following the Visium HD Spatial Applications Imaging Guidelines [46].

- Tissue Permeabilization: Optimize permeabilization conditions to release mRNA from tissue sections while preserving spatial information. This is critical for achieving high mRNA capture efficiency, particularly in dense tumor regions [42].

- cDNA Synthesis and Library Construction: Follow the Visium HD Spatial Gene Expression Reagent Kits User Guide for cDNA synthesis, amplification, and library preparation [42]. The protocol requires the CytAssist instrument with Firmware v2.0.0 or higher for spatial barcoding.

Critical Considerations for TME Studies:

- Preserve tissue morphology throughout the process, as architectural features are essential for interpreting spatial patterns in the TME [46].

- For immunology-focused TME studies, IF staining can be combined with spatial transcriptomics to simultaneously profile protein markers and whole transcriptome [46].

- Include appropriate controls and follow the Visium HD Protocol Planner for efficient experimental design and reagent management [43].

Slide-seq Protocol for CNA Detection in Tumors

The Slide-seq protocol enables high-resolution spatial transcriptomics that can be leveraged to infer copy number alterations (CNAs) in tumor tissues when combined with computational tools like SlideCNA [41].

Experimental Workflow:

- Bead Array Preparation: Create high-density arrays of DNA-barcoded beads with known spatial positions. Each bead contains uniquely barcoded oligonucleotides with PCR handles, spatial barcodes, and poly(dT) sequences for mRNA capture.

- Tissue Sectioning and Transfer: Cryosection fresh frozen tissues at 10 µm thickness and transfer sections onto the bead array, ensuring complete contact between tissue and beads.

- mRNA Capture and Library Preparation: Capture polyadenylated RNA transcripts onto the spatially barcoded beads. Perform on-bead reverse transcription to generate spatially barcoded cDNA, followed by amplification and library construction for sequencing.

SlideCNA Computational Analysis for CNAs:

- Spatial Binning: Overcome data sparsity by combining neighboring beads into bins based on both expression profiles and physical proximity. This increases signal while maintaining spatial structure [41].

- Reference Selection: Define a set of reference beads/spots corresponding to non-malignant cell populations (e.g., immune cells, stromal cells) identified through cell type annotation.

- CNA Score Calculation: Adjust expression values by the average expression of reference beads for each gene, then smooth expression across chromosomes using a weighted pyramidal average scheme.

- Spatial Subclone Detection: Identify regions with distinct CNA profiles using clustering algorithms, enabling mapping of tumor subclones across the tissue landscape [41].

Stereo-seq V2 for Total RNA Profiling in FFPE Samples

Stereo-seq V2 enables comprehensive spatial profiling of total RNA from FFPE tissues, which is particularly valuable for clinical cancer samples [45].

Experimental Protocol:

- FFPE Section Preparation: Cut 5-10 µm sections from FFPE tissue blocks and mount on Stereo-seq chips. Deparaffinize and rehydrate sections using standard protocols.

- Probe Hybridization and Extension: Employ random primers rather than poly(dT) primers to capture both polyadenylated and non-polyadenylated RNAs. The random primers hybridize to RNAs in situ and are extended to generate cDNA [45].

- Spatial Barcoding and Library Construction: Transfer the synthesized cDNA to a second-round reaction chamber where it is tagged with spatial barcodes. Amplify the barcoded cDNA and prepare sequencing libraries.

- Sequencing and Data Analysis: Sequence libraries and align reads to the reference genome. The random-priming strategy provides "unbiased transcript capturing" and "uniform gene body coverage," enabling detection of non-polyadenylated RNAs and alternative splicing events [45].

Application in Tuberculosis Research: Stereo-seq V2 has been applied to a Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb)-infected mouse model to simultaneously monitor host and pathogen transcriptomes, assemble immune repertoires, and identify Mtb-specific BCR clones, demonstrating its utility in infectious disease and cancer immunology [45].

Applications in Tumor Microenvironment Characterization

Dissecting Cellular Heterogeneity and Communication

The integration of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) with spatial transcriptomics has transformed our ability to resolve cellular heterogeneity and communication networks within the TME [40]. While scRNA-seq identifies distinct cellular subpopulations and rare cell types, ST places these findings within the spatial context of the tumor tissue [15]. This combined approach has revealed spatially organized tumor-stroma crosstalk, such as the colocalization of stress-associated cancer cells with inflammatory fibroblasts in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, with the latter identified as major producers of interleukin-6 (IL-6) [40].

The following diagram illustrates the workflow for integrating scRNA-seq and ST data to characterize the TME.

Identifying Therapeutic Targets and Resistance Mechanisms

Spatial transcriptomics enables the identification of novel therapeutic targets and resistance mechanisms by mapping the spatial distribution of key signaling pathways within the TME. Important pathways that can be characterized include vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), programmed cell death protein 1/programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-1/PD-L1), cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4), and various extracellular matrix (ECM) pathways [15]. For example, ST can reveal the spatial relationships between immune checkpoint expressions and immune cell localization, providing insights into immune evasion mechanisms and potential biomarkers for immunotherapy response [15] [40].

The application of iSCALE—a machine learning framework that predicts gene expression for large-sized tissues with cellular-level resolution—has demonstrated particular utility in identifying critical tissue structures in cancer samples. In gastric cancer, iSCALE accurately identified the boundary between poorly cohesive carcinoma regions with signet ring cells and adjacent gastric mucosa, as well as detected tertiary lymphoid structures (TLS) associated with improved immune responses and better patient prognosis [39].

Analyzing Large Tissue Sections and Clinical Applications

A significant limitation of conventional ST platforms is their restricted tissue capture area (typically 6.5 mm × 6.5 mm for Visium HD), which often misses key biological regions in large clinical specimens [39]. The iSCALE framework addresses this limitation by leveraging the gene expression-histological feature relationship learned from a small set of training ST captures to predict gene expression across entire large tissue sections [39]. This approach enables comprehensive analysis of large clinical samples, making spatial transcriptomics more applicable to standard clinical pathology workflows.

For analyzing large tissues, the following protocol is recommended:

- Select Training Regions: Choose multiple regions from the same tissue block that fit standard ST platform capture areas to generate "daughter captures" [39].

- Spatial Alignment: Implement spatial clustering analysis on the daughter ST data and align them onto the whole-slide "mother image" through a semiautomatic process [39].

- Model Training and Prediction: Train a neural network to learn the relationship between histological image features and gene expression, then predict gene expression across the entire large tissue section at 8-µm × 8-µm superpixel resolution [39].

Technical Considerations and Future Directions