The Secret Shuttles of Sweet Wormwood

Unlocking a Malaria Drug's Hidden Potential

Malaria cases annually worldwide

Deaths from malaria each year

Artemisinin yield from Artemisia annua

Introduction

Imagine a plant that holds the key to fighting one of humanity's oldest and deadliest diseases: malaria. This plant is Artemisia annua, or sweet wormwood, and its potent weapon is a molecule called artemisinin. This powerful compound is the cornerstone of modern malaria treatments, saving millions of lives. But there's a problem: the plant produces it in painfully small quantities, making it expensive and sometimes in short supply.

For decades, scientists have been trying to solve this production puzzle. Now, they're looking beyond the artemisinin factories themselves and focusing on the plant's internal "cellular shuttles"—proteins that may hold the secret to boosting the yield of this life-saving medicine.

Artemisia annua, the source of artemisinin

The Cellular Superhighway: What Are ABCG Transporters?

Think of a plant cell as a bustling city. Within its walls (the cell membrane), factories are producing valuable goods—like artemisinin. But how does the finished product get out of the factory and to its final destination, whether that's stored in another part of the cell or secreted out to protect the plant?

This is where transporters come in. They are the trucks, trains, and cargo ships of the cellular world. A particularly important family of these is the ABCG transporters.

- ATP-binding cassette G transporters are tiny protein machines embedded in cell membranes.

- They use energy (from a molecule called ATP) to pump various substances across the membrane, acting like powered gatekeepers.

- They can move compounds out of the cell or into storage compartments like vacuoles.

Cellular Transport Mechanism

In Artemisia annua, researchers had a brilliant hypothesis: What if certain ABCG transporters are specifically responsible for shuttling artemisinin or its building blocks? If they could find these specific "shuttles," they might be able to supercharge them, guiding the plant to accumulate more of the precious drug.

A Plant's Cry for Help: The Signals That Trigger Defense

Plants don't have an immune system like ours. Instead, they produce a cocktail of defensive chemicals when under attack. Artemisinin is one such defense compound, deployed to fend off pests and fungi.

Scientists can mimic this "attack" in the lab using plant hormones. Two key players are:

Methyl Jasmonate (MeJA)

Often called the plant's "wound signal." When a leaf is chewed by an insect, MeJA is released, alerting the rest of the plant to ramp up its defense production.

Abscisic Acid (ABA)

Known as the "stress hormone," it's produced in response to drought or other environmental stresses, often triggering similar defense pathways.

By applying these hormones, researchers can essentially "trick" the plant into going on high alert and producing more artemisinin, all while watching which transporters spring into action.

Defense Activation Timeline

0-2 hours

Stress signal detection

2-6 hours

Hormone production (MeJA/ABA)

6-12 hours

Defense gene activation

12-24 hours

Artemisinin production increases

24+ hours

Maximum artemisinin levels

The Detective Work: Pinpointing the Key Shuttles

A recent study set out to play detective, aiming to identify which of the many ABCG transporter genes in Artemisia annua were the most likely suspects involved in artemisinin transport.

Methodology: A Step-by-Step Investigation

The research followed a logical, multi-step process:

Genetic Lineup

Scientists sifted through the plant's genetic database to create a complete list of all its ABCG transporter genes—the potential "suspects." They identified 25 candidates.

Tissue Test

They analyzed where these genes were active in different parts of the plant. Genes responsible for artemisinin transport should be most active in leaves and floral buds.

Hormone Interrogation

They treated plants with MeJA and ABA, then tracked which transporter genes showed significant changes in activity in sync with artemisinin production genes.

Correlation Analysis

They performed statistical analysis to see which ABCG transporter gene activities correlated most strongly with actual artemisinin yield.

Results and Analysis: The Shuttles Are Revealed

The results were striking. The study wasn't a wild goose chase; it successfully narrowed down the list of 25 genes to a handful of high-probability candidates.

Key Findings

- Tissue-Specific Expression: Several genes (like AaABCG6 and AaABCG7) were highly active specifically in the leaves and floral buds, perfectly matching the artemisinin production profile.

- Response to Hormones: Key genes showed a dramatic response to MeJA and ABA treatments. Their activity skyrocketed, often in a similar pattern to the known artemisinin biosynthesis genes.

The most crucial evidence came from the correlation analysis. The data below shows how the activity of certain transporter genes was tightly linked to the final artemisinin content.

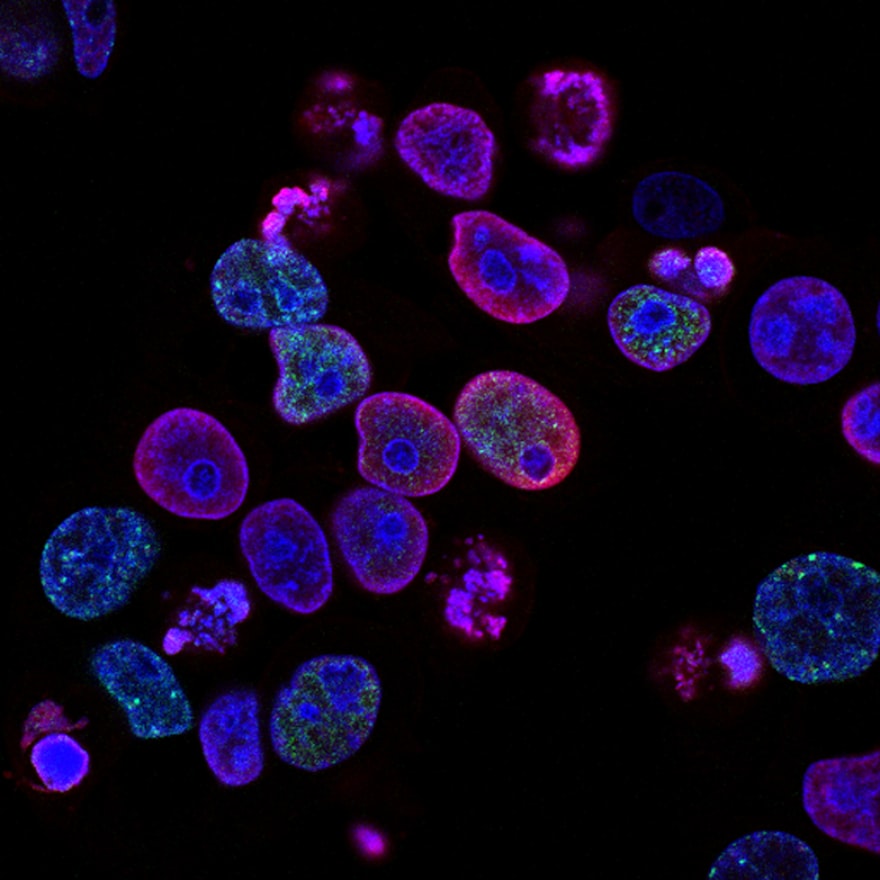

Gene Expression Visualization

Data Tables: Connecting the Dots

Table 1: Tissue-Specific Expression of Top Candidate Genes

(Expression Level: Low (+), Medium (++), High (+++))| Gene Name | Roots | Stems | Leaves | Flowers | Key Takeaway |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AaABCG6 | + | ++ | +++ | +++ | Highly active in artemisinin-rich tissues |

| AaABCG7 | + | + | +++ | +++ | Highly active in artemisinin-rich tissues |

| AaABCG12 | ++ | ++ | + | + | Not specialized for artemisinin |

| AaABCG25 | +++ | + | + | + | Likely has a root-specific function |

Table 2: Gene Response to Hormone Treatments

(Fold-Increase in Expression after 24 hours)| Gene Name | Control (No Treatment) | Methyl Jasmonate (MeJA) | Abscisic Acid (ABA) |

|---|---|---|---|

| AaABCG6 | 1.0 | 12.5 | 8.2 |

| AaABCG7 | 1.0 | 15.8 | 9.5 |

| AaABCG12 | 1.0 | 2.1 | 1.5 |

| Artemisinin Biosynthesis Gene | 1.0 | 14.2 | 10.1 |

Table 3: Correlation Between Gene Expression and Artemisinin Yield

| Gene Name | Correlation Coefficient (r) | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| AaABCG7 | 0.89 | Very High |

| AaABCG6 | 0.85 | Very High |

| Artemisinin Biosynthesis Gene | 0.92 | Very High |

| AaABCG12 | 0.35 | Low |

Note: A correlation coefficient (r) close to 1.0 means the two factors are perfectly linked; when one goes up, the other goes up in a predictable way.

Analysis

The data tells a compelling story. AaABCG6 and AaABCG7 are the prime suspects. They are in the right place (leaves and flowers), they respond to the right signals (MeJA and ABA), and their activity is strongly correlated with how much artemisinin the plant ultimately produces .

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Here's a look at the essential tools that made this discovery possible:

Methyl Jasmonate (MeJA)

A plant hormone used to simulate an insect attack, triggering the plant's natural defense pathways and artemisinin production.

Abscisic Acid (ABA)

A plant stress hormone used to mimic drought conditions, which also stimulates the production of defensive compounds like artemisinin.

qRT-PCR Machine

The workhorse instrument for measuring gene expression. It allows scientists to precisely quantify how active a specific gene is in a tissue sample.

Artemisinin Standard

A pure sample of artemisinin used as a reference to accurately measure and quantify the amount of artemisinin extracted from the plant tissues.

Gene Sequence Database

A digital library of Artemisia annua's genetic code, which researchers mined to identify all the ABCG transporter genes in the first place.

Statistical Software

Advanced analytical tools used to perform correlation analysis and determine the relationship between gene expression and artemisinin yield.

Conclusion: Cultivating a Brighter Future

This research is more than just an academic exercise. By identifying AaABCG6 and AaABCG7 as the putative transporters for artemisinin, scientists have unlocked a powerful new strategy in the fight against malaria.

The next steps are clear: using modern genetic tools, plant biologists can now work on breeding or engineering Artemisia annua plants with hyper-active versions of these shuttle proteins. The goal is to create super-producer plants that efficiently channel more building blocks into artemisinin and store more of the final product .

In the quest for a reliable and affordable supply of artemisinin, understanding the plant's internal logistics network has proven to be a game-changer. The humble cellular shuttle, once an obscure protein, is now steering us toward a future where this life-saving drug is within everyone's reach.

Future Impact

Potential to increase artemisinin yields by optimizing transporter activity, making malaria treatment more accessible worldwide.