Validating Cancer Stem Cell Biomarkers: From Bench to Bedside in Precision Oncology

The validation of reliable cancer stem cell (CSC) biomarkers is a critical frontier in oncology, holding the potential to revolutionize cancer diagnosis, prognosis, and therapeutic development.

Validating Cancer Stem Cell Biomarkers: From Bench to Bedside in Precision Oncology

Abstract

The validation of reliable cancer stem cell (CSC) biomarkers is a critical frontier in oncology, holding the potential to revolutionize cancer diagnosis, prognosis, and therapeutic development. This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and drug development professionals, exploring the foundational biology of CSCs and the significant challenge posed by their heterogeneity and the lack of universal markers. It delves into advanced methodological frameworks for biomarker identification and validation, from single-cell omics to functional assays. The content further addresses major troubleshooting areas, including overcoming technological limitations and CSC plasticity, and culminates in a comparative evaluation of validation strategies and their translation into targeted therapies and clinical trials. By synthesizing current knowledge and emerging trends, this article serves as a roadmap for advancing robust CSC biomarker validation to eradicate therapy-resistant cell populations and improve patient outcomes.

The CSC Biomarker Landscape: Understanding Heterogeneity, Key Markers, and Biological Challenges

Defining the Cancer Stem Cell Niche and Its Role in Therapy Resistance and Metastasis

The cancer stem cell (CSC) niche is a specialized tumor microenvironment that plays a pivotal role in maintaining stemness, driving therapy resistance, and promoting metastatic spread. This structured guide compares the cellular components, molecular features, and therapeutic targeting strategies of CSC niches across different cancer types, supported by experimental data and methodologies. We summarize key biomarkers and niche characteristics in clearly organized tables, provide detailed experimental protocols for studying CSC-niche interactions, and visualize critical signaling pathways. Within the broader context of validating CSC biomarkers across cancer types, this analysis reveals both conserved and tumor-specific niche mechanisms that represent promising therapeutic targets for overcoming treatment resistance.

Cancer stem cells (CSCs) constitute a minor subpopulation within tumors characterized by self-renewal capacity, differentiation potential, and enhanced resistance to conventional therapies [1] [2]. These cells are situated in specialized microenvironments termed "CSC niches" that provide critical signals for maintaining stemness and regulating CSC fate decisions [1] [3]. The niche concept was originally proposed by Schofield in 1978 for hematopoietic stem cells and has since been extended to solid tumors, where these specialized microterritories maintain self-renewal, guide differentiation, and respond to microenvironmental cues such as oxygenation, mechanical stresses, and soluble factors [4].

CSC niches demonstrate remarkable spatial organization, with recent research using ultra-wide field microscopy revealing that CSCs cluster together and are spatially separated from differentiated cancer cells, forming patterns resembling niches even in unperturbed conditions [5]. The bidirectional crosstalk between CSCs and their niche creates a dynamic ecosystem that supports tumor progression, metastatic dissemination, and therapy resistance through both intrinsic CSC properties and extrinsic microenvironmental factors [6] [3]. Understanding this complex interplay is essential for developing effective strategies to target CSCs and overcome treatment failure.

Composition and Characteristics of the CSC Niche

The CSC niche comprises diverse cellular and acellular components that collectively create a protective microenvironment sustaining CSC function. Table 1 summarizes the major niche constituents and their functional roles across different cancer types.

Table 1: Cellular and Molecular Components of the CSC Niche

| Component Type | Specific Elements | Functional Role in CSC Niche | Cancer Types Where Documented |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cellular Components | Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts (CAFs) | Secrete stemness-maintaining factors (e.g., CLCF1); induce therapy resistance [3] | Gastric, pancreatic, breast cancer |

| Tumor-Associated Macrophages (TAMs) | Promote immune evasion; support stemness through cytokine secretion [6] [3] | Glioblastoma, breast cancer | |

| Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) | Enhance self-renewal through direct contact and paracrine signaling [3] | Multiple solid tumors | |

| Endothelial Cells & Pericytes | Form vascular niches; regulate CSC quiescence and activation [7] [8] | Glioblastoma, colorectal cancer | |

| Extracellular Matrix | Type I Collagen, Fibronectin | Increase matrix stiffness; promote CSC proliferation and inhibit apoptosis [3] | Breast cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma |

| Hyaluronan | Maintains multipotent state; supports CSC marker expression [3] | Liver cancer | |

| Physiological Conditions | Hypoxia | Activates HIF signaling; upregulates CSC markers (CD133, CD44); promotes quiescence [8] | Multiple solid tumors |

| Inflammation | Creates pro-tumorigenic signaling environment; enhances plasticity [3] | Colorectal, pancreatic cancer | |

| Acidic pH | Contributes to therapy resistance; alters CSC metabolism [3] | Multiple solid tumors |

Spatial analysis of CSC distribution reveals that niches are not randomly organized within tumors. CSCs with high clonal formation and invasion capabilities predominantly localize at the invasive frontier of tumors, where extracellular matrix (ECM) stiffness is significantly higher compared to the tumor core [3]. This spatial organization is functionally important, as mechanical factors like matrix stiffness can trigger stemness in non-stem cancer cells and regulate CSC marker expression [3]. The biomechanical properties of the niche, therefore, represent a crucial regulatory element in CSC biology.

Experimental Models and Methodologies for Studying CSC Niches

Key Experimental Protocols

Research into CSC-niche interactions employs specialized methodologies to isolate CSCs, model their microenvironment, and track dynamic behaviors:

CSC Isolation and Identification: The gold standard for CSC identification combines sphere colony formation assays with in vivo xeno transplantation of tumor cells into immunodeficient mice [8]. Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) and Magnetic-Activated Cell Sorting (MACS) are routinely used to isolate CSCs based on surface markers such as CD44, CD133, EpCAM, and ALDH activity [9]. For instance, as few as 100 CD44+/CD24- cells can initiate tumors in immunocompromised mice, demonstrating their tumor-initiating capacity [1] [9].

Spatiotemporal Imaging of CSC Niches: Ultra-wide field microscopy enables tracking of thousands of individual cells over several days using stemness reporters such as pALDH1A1:mNeptune [5]. This approach allows for single-cell tracking and analysis of phenotypic transitions, revealing that CSC reprogramming is influenced by the phenotypic state of neighboring cells—promoted by CSCs and inhibited by differentiated cancer cells in the immediate vicinity [5].

3D Organoid and Co-culture Models: 3D organoid systems recapitulate the tumor microenvironment by incorporating stromal components such as CAFs and immune cells alongside CSCs [2]. These models permit the investigation of niche-mediated therapy resistance and metabolic symbiosis in conditions that mimic in vivo settings.

The following diagram illustrates a representative experimental workflow for analyzing CSC-niche interactions:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for CSC Niche Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Experimental Function | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| CSC Markers | CD44, CD133, ALDH, EpCAM | Isolation and identification of CSC populations | FACS/MACS sorting; immunohistochemistry |

| Stemness Reporters | pALDH1A1:mNeptune | Visualization of stem-like phenotypes in live cells | Real-time tracking of phenotypic transitions [5] |

| Niche Modeling Components | Type I Collagen, Laminin, Fibronectin | Recapitulation of ECM stiffness and composition | 3D organoid cultures; invasion assays [3] |

| Signaling Pathway Modulators | Wnt/β-catenin antagonists (sFRP4), Notch inhibitors | Dissection of niche signaling mechanisms | Functional studies of stemness pathways [1] |

| Cytokine/Chemokine Assays | IL-6, BDNF, NGF, CCL5 detection kits | Analysis of niche-derived paracrine signals | Evaluation of CSC-stroma crosstalk [5] [3] |

Signaling Pathways in CSC Niche Maintenance

Several evolutionarily conserved signaling pathways play critical roles in mediating niche signals that regulate CSC self-renewal, plasticity, and therapy resistance. The following diagram illustrates the key pathways and their interconnections:

The Wnt/β-catenin pathway demonstrates particular importance in niche signaling. Upregulation of Wnt/β-catenin promotes expression of stemness markers (CD44, ALDH) and drug resistance transporters (ABCG2, ABCC4) in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma [1]. This pathway can be counteracted using sFRP4, a Wnt antagonist that reverses both drug resistance and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) markers [1].

Hypoxia-inducible factors (HIFs), especially HIF-1α, serve as master regulators of the niche response to low oxygen tension. HIF activation promotes CSC proliferation, self-renewal, and tumorigenicity while upregulating surface markers like CD133 and CD44 [8]. The hypoxic niche protects CSCs from DNA damage caused by oxidative stress and contributes to therapy resistance, as radiation has been shown to double HIF-1 activity within 24-48 hours post-exposure [8].

Notch and Hedgehog signaling pathways additionally contribute to niche-mediated CSC maintenance. In breast CSCs and oral squamous cell carcinoma, Notch signaling promotes self-renewal and controls expression of EMT regulators like SLUG and TWIST [1]. Hedgehog pathway overexpression maintains self-renewal in lung squamous cell carcinoma, glioma, colon, and breast cancers through regulation of pluripotency factors OCT4, SOX2, and BMI1 [1].

Role of the CSC Niche in Therapy Resistance and Metastasis

Therapy Resistance Mechanisms

CSC niches contribute to treatment failure through multiple interconnected mechanisms:

Physical Protection: The ECM in CSC niches physically shelters CSCs from therapeutic agents [1]. Increased matrix stiffness from collagen and laminin deposition enhances this protective effect [3].

Metabolic Adaptations: Hypoxic conditions within niches shift CSCs toward anaerobic glycolysis, reducing dependence on mitochondrial function and decreasing susceptibility to oxidative stress-induced damage [8].

Enhanced DNA Repair: CSCs in specialized niches exhibit preferential activation of DNA damage response pathways. Following radiation treatment in glioblastoma, CSC populations increased 2-4-fold due to enhanced DNA repair capabilities [1].

Immune Evasion: Niches create immune-privileged sites through multiple strategies, including upregulated immune checkpoint proteins (PD-L1, B7-H4), recruitment of immunosuppressive cells (Tregs, MDSCs), and reduced MHC class I expression [6].

Cellular Plasticity: Under therapeutic pressure, non-CSCs can dedifferentiate into CSC-like states through niche-mediated signals. This plasticity represents a major mechanism of acquired resistance [6].

Metastatic Dissemination

The CSC niche plays a critical role in metastatic progression by regulating the behavior of metastatic stem cells (MetSCs)—disseminated cancer cells capable of reinitiating tumor growth in distant tissues [7]. Key niche functions in metastasis include:

Dormancy Regulation: Niches maintain disseminated tumor cells (DTCs) in a quiescent, non-proliferative state that is resistant to conventional antimitotic therapies [7]. Bone marrow niches particularly excel at maintaining this dormant state.

Pre-metastatic Niche Formation: CSCs prime future metastatic sites by secreting factors that create a supportive microenvironment before arrival of disseminated cells [7] [3].

Stemness Maintenance at Secondary Sites: Successful metastases require maintenance of CSC properties in foreign microenvironments. CD44+ gastric CSCs demonstrate self-renewal and differentiation capacity that enables establishment of secondary tumors [9].

Table 3: Biomarker Validation Across Cancer Types and Clinical Implications

| Biomarker | Cancer Types | Role in Therapy Resistance | Association with Metastasis |

|---|---|---|---|

| CD44 | Breast, colorectal, pancreatic, gastric, ovarian [9] | High expression associated with chemoresistance; CD44v isoforms increase tumor initiation frequency in gastric cancer [9] | CD44+ populations show enhanced metastatic potential in xenograft models [9] |

| CD133 | Glioblastoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, colon, ovarian [9] | CD133+ cells exhibit increased chemo- and radioresistance in glioblastoma [1] [9] | CD133+CD44+ population in HCC produces intrahepatic and lung metastases [9] |

| ALDH | Head and neck SCC, breast, ovarian [9] | ALDH activity confers resistance to chemotherapeutic agents through detoxification [9] | ALDHhighCD44+ cells mediate metastatic capability in breast cancer [9] |

| EpCAM | Breast, colon, HCC, pancreatic [9] | EpCAM+ CSCs contribute to therapy resistance and recurrence | EpCAM+/CD133+ HCC cells demonstrate metastatic stem cell properties [9] |

Concluding Perspectives and Future Directions

The CSC niche represents a compelling therapeutic target for overcoming treatment resistance and preventing metastatic spread across cancer types. Future research directions should focus on:

Therapeutic Targeting of Niche Components: Strategies including niche-disrupting agents, immune checkpoint modulators specific to CSCs, and metabolic reprogramming approaches hold promise for clinical translation [2] [6].

Biomarker Validation: While markers like CD44, CD133, and ALDH have been established across multiple cancers, further validation is needed to address tumor-type specificities and functional heterogeneity [10] [9].

Advanced Modeling Techniques: Integrating single-cell sequencing, spatial transcriptomics, and AI-driven multiomics analysis will provide unprecedented resolution of niche architecture and function [2].

Dual-Targeting Approaches: Combining CSC-directed therapies with conventional treatments may prevent the repopulation of tumors from therapy-resistant CSCs, addressing the fundamental challenge of relapse [9].

Understanding the complex heterogeneity of CSC niches remains a prerequisite for designing superior therapeutic strategies that target both CSCs and their supportive microenvironments. As research continues to unravel the dynamic interplay between CSCs and their niches, new opportunities will emerge for developing more effective combination therapies aimed at eliminating the root causes of treatment failure and metastasis.

The cancer stem cell (CSC) paradigm has revolutionized our understanding of tumor development, progression, and therapeutic resistance. CSCs constitute a highly plastic and therapy-resistant cell subpopulation within tumors that drives tumor initiation, progression, metastasis, and relapse [2] [11]. Despite substantial progress in characterizing CSC biology, the field faces a fundamental obstacle: the lack of universally reliable CSC biomarkers and significant tissue-specific variation in marker expression [2]. This dual challenge impedes consistent identification, isolation, and targeting of CSCs across different cancer types, presenting a critical bottleneck in both basic research and clinical translation.

The absence of universal biomarkers stems from the profound molecular heterogeneity of CSCs and their dynamic nature. CSCs represent reversible states along developmental and treatment-induced trajectories rather than a fixed, intrinsic phenotype [12]. Their identity is shaped by both intrinsic genetic programs and extrinsic cues from the tumor microenvironment [2]. Furthermore, stem-like features can be acquired de novo by non-CSCs in response to environmental stimuli such as hypoxia, inflammation, or therapeutic pressure, indicating that CSCs may represent a dynamic functional state rather than a static subpopulation [2]. This plasticity fundamentally challenges the notion of a fixed CSC hierarchy and highlights the necessity for context-specific, function-based approaches in CSC research and therapy development.

Current Landscape of CSC Biomarkers: A Comparative Analysis

Established Markers and Their Limitations

The quest for reliable CSC biomarkers has predominantly focused on cell surface proteins, enzymatic activity, and functional characteristics. The table below summarizes the most widely utilized CSC markers across different cancer types, highlighting their tissue-specific expression patterns and limitations.

Table 1: Established CSC Biomarkers Across Different Cancer Types

| Biomarker | Cancer Types with Reported Expression | Key Limitations | Functional Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| CD44 | Breast, pancreatic, prostate, colorectal, head and neck | Also expressed on normal stem cells and activated lymphocytes [2] | Cell adhesion, hyaluronan receptor, activates pro-survival signaling [13] |

| CD133 | Glioblastoma, colon, pancreatic, liver | Expression varies with tumor stage and hypoxia; not cancer-specific [2] [14] | Membrane glycoprotein, modulates autophagy and stemness maintenance |

| ALDH1 | Breast, lung, colon, ovarian, pancreatic | Multiple isoforms with tissue-specific expression patterns [13] | Detoxifying enzyme, retinoic acid metabolism, drug resistance [11] |

| EpCAM | Colorectal, pancreatic, prostate, ovarian | Expression influenced by epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) [2] | Epithelial cell adhesion, Wnt signaling modulation |

| LGR5 | Colorectal, gastric, intestinal cancers | Limited to specific tissue types; marks normal stem cells [2] | Wnt pathway receptor, maintains stem cell identity |

| CD44v6 | Colorectal, pancreatic, gastric | Specific isoform requiring specialized detection methods | Metastasis promotion, growth factor receptor signaling |

The fundamental limitation of these markers is their lack of exclusivity to CSCs. As noted in recent research, "although surface proteins such as CD44 and CD133 have been widely used to isolate CSC populations, these markers are not exclusive to CSCs and are often expressed in normal stem cells (NSCs) or non-tumorigenic cancer cells" [2]. This creates significant challenges in distinguishing CSCs from normal tissue stem cells during therapeutic interventions, raising concerns about potential on-target, off-tumor toxicity.

Tissue-Specific Variation in CSC Marker Expression

The expression of CSC markers demonstrates remarkable variation across different tissue types and cancer lineages, reflecting the influence of tissue origin and microenvironmental context on CSC phenotypes. The table below illustrates this tissue-specific variation, emphasizing how marker utility depends heavily on cancer type.

Table 2: Tissue-Specific Variation in CSC Marker Expression Patterns

| Cancer Type | Primary CSC Markers | Secondary/Context-Dependent Markers | Notes on Heterogeneity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Breast Cancer | CD44+/CD24-/low, ALDH1+ [2] | EpCAM, SOX2 | CD44+/CD24- and ALDH1+ populations partially overlap |

| Glioblastoma | CD133+, Nestin+, SOX2+ [2] | SSEA-1, L1CAM, A2B5 | Marker expression influenced by hypoxia and vascular niches |

| Colorectal Cancer | LGR5+, CD133+, CD44+ [2] | CD166, EpCAM, ALDH1 | Spatial heterogeneity along crypt-axis and tumor regions |

| Pancreatic Cancer | CD133+, CD44+, CXCR4+ | c-Met, ALDH1, ESA | Markers associated with metastatic potential and therapy resistance |

| Prostate Cancer | CD44+, CD133+, ITGA2+ | ALDH1, Trop2 | Marker expression changes with disease progression to castration resistance |

| Lung Cancer | CD133+, CD44+, ALDH1+ | SOX2, Oct-4 | Lineage-specific variations between NSCLC and SCLC |

| Melanoma | ABCB5+, CD271+ | ALDH1, JARID1B | Dynamic marker expression influenced by microenvironment |

This tissue-specific variation presents substantial challenges for developing pan-cancer CSC targeting strategies. For instance, glioblastoma CSCs frequently express neural lineage markers such as Nestin and SOX2, whereas gastrointestinal cancers may harbor CSCs characterized by LGR5 or CD166 expression [2]. This diversity suggests that CSC identity is shaped by both cell-of-origin signatures and adaptation to local microenvironmental niches.

Methodological Approaches for CSC Identification and Validation

Standard Experimental Protocols

Overcoming the challenges of CSC biomarker validation requires rigorous methodological approaches that combine surface marker analysis with functional validation. The following experimental protocols represent the current gold standards in the field.

Table 3: Core Methodologies for CSC Identification and Validation

| Method Category | Specific Protocol | Key Output Measures | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surface Marker-Based Isolation | Flow cytometry with antibody conjugates (e.g., CD44-APC/CD24-PE) | Percentage of marker-positive population, intensity of expression | Requires appropriate isotype controls and compensation panels [13] |

| Functional Assays | Sphere formation in serum-free, non-adherent conditions [13] | Number and size of primary and secondary spheres | Passage number affects stemness properties; matrix composition influences results |

| Enzymatic Activity Assays | Aldefluor assay for ALDH activity [13] | ALDH-high population percentage, inhibition by DEAB | Enzyme activity varies with cell cycle and metabolic state |

| In Vivo Validation | Limiting dilution transplantation in immunocompromised mice [11] [13] | Tumor-initiating cell frequency, tumor latency, histology | Strain selection (NSG > NOD/SCID > SCID) significantly impacts engraftment rates |

| Clonal Lineage Tracing | Lentiviral barcoding and sequencing | Phylogenetic trees of tumor evolution, stem cell dynamics | Requires single-cell sequencing and bioinformatic reconstruction |

The integration of these complementary approaches is essential for comprehensive CSC characterization. As emphasized in recent methodological reviews, "the gold standard for CSC validation remains in vivo tumorigenicity assays, wherein sorted cells are injected into immunocompromised mice to evaluate their tumor-initiating potential" [13]. This functional validation is particularly crucial given the limitations of surface markers alone.

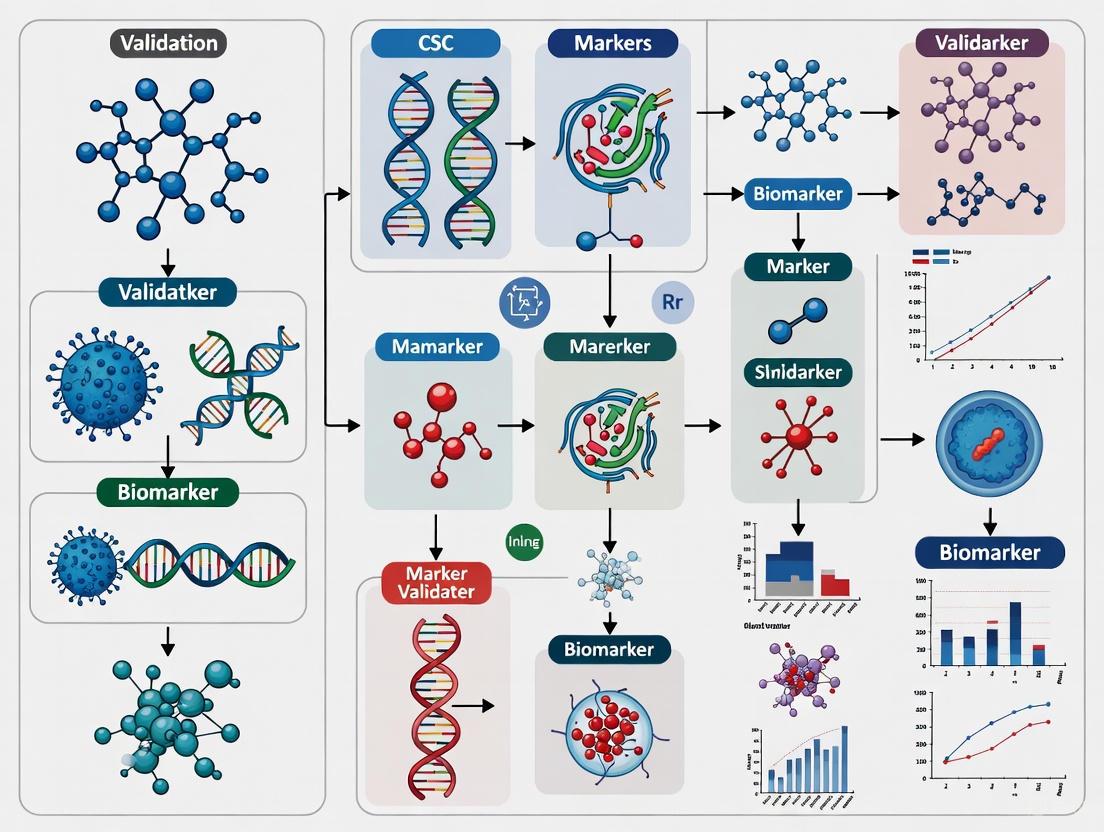

CSC Validation Workflow

The diagram below illustrates the integrated experimental workflow for CSC identification and validation, combining multiple methodological approaches to overcome the limitations of individual techniques.

Emerging Technologies and Future Directions

Advanced Approaches for CSC Characterization

Novel technological platforms are increasingly enabling researchers to move beyond traditional surface markers and embrace a more dynamic, functional definition of CSCs. Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has transformed our understanding of tumor biology by enabling high-resolution profiling of rare subpopulations (<5%) and revealing the functional heterogeneity that contributes to treatment failure [12]. Supported by advanced bioinformatics tools, these approaches now enable the dynamic characterization of CSC potential at unprecedented resolution.

Table 4: Computational Tools for CSC Stemness Assessment

| Tool Name | Algorithm Basis | Application Context | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| CytoTRACE | Gene counts and expression | Developmental potential inference | Marker-free approach, web server available [12] |

| StemID | Shannon entropy | Stemness quantification from scRNA-seq | Identifies intermediate cell states [12] |

| SCENT | Signaling entropy | Cell potency and differentiation potential | Uses protein-protein interaction networks [12] |

| mRNAsi | Machine learning | Stemness index based on transcriptome | Pan-cancer application, TCGA-compatible [12] |

| StemSC | Relative expression orderings | Stemness comparison across samples | Robust to batch effects and normalization [12] |

| scEpath | Energy landscape modeling | Inference of transition probabilities | Models epigenetic barriers between states [12] |

These computational approaches are particularly valuable because they "enable the dynamic characterization of CSC potential at unprecedented resolution" and challenge the traditional view of CSCs as "rare but static entities," suggesting instead that "stemness might be a rather dynamic, context-dependent state" [12].

Research Reagent Solutions for CSC Studies

The table below outlines essential research tools and reagents critical for advancing CSC biomarker discovery and validation efforts.

Table 5: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for CSC Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Primary Applications | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Validated Antibody Panels | CD44-PE, CD24-FITC, CD133/1-APC | Flow cytometry, immunofluorescence | Clone validation across species, titration for specific applications |

| ALDH Activity Detection | Aldefluor Kit, DEAB inhibitor | Functional CSC identification | Optimization for different cell types, viability controls |

| 3D Culture Matrices | Matrigel, synthetic hydrogels | Sphere formation assays, organoid culture | Batch-to-batch variability, growth factor composition |

| CSC Functional Assay Kits | SphereCulture Medium, Extreme Limiting Dilution Analysis software | Self-renewal quantification | Serum-free formulation, growth factor supplementation |

| Single-Cell Multi-omics Kits | 10x Genomics Chromium, Parse Biosciences | High-resolution CSC profiling | Cell viability requirements, sequencing depth requirements |

| In Vivo Validation Models | NSG mice, patient-derived xenografts | Tumor-initiating cell assessment | Ethical considerations, engraftment timeframes |

The fundamental challenge of universal CSC biomarkers persists due to the dynamic nature of CSCs, their phenotypic plasticity, and extensive tissue-specific variation. No single marker or methodology currently suffices for comprehensive CSC identification across cancer types. The most promising path forward involves integrated approaches that combine multiple surface markers with functional assays and in vivo validation, while leveraging emerging single-cell technologies and computational tools.

Future efforts should focus on developing tissue-specific biomarker panels validated through multi-institutional consortia, establishing standardized protocols for CSC assessment, and creating reference databases that capture the dynamic spectrum of CSC states across different cancer types. As the field moves toward these goals, acknowledging and systematically addressing the core challenge of biomarker variability remains essential for advancing both basic CSC biology and the development of effective CSC-targeted therapies.

Established and Emerging CSC Surface Markers (CD44, CD133, ALDH1, EpCAM)

Cancer stem cells (CSCs) constitute a highly plastic and therapy-resistant cell subpopulation within tumors that drives tumor initiation, progression, metastasis, and relapse [2]. Their ability to evade conventional treatments, adapt to metabolic stress, and interact with the tumor microenvironment makes them critical targets for innovative therapeutic strategies [2]. The clinical detection and targeting of CSCs represent a major challenge in oncology, primarily due to the lack of specific and reliable biomarkers [15].

The identification of CSCs largely relies on specific surface markers that enable their isolation and characterization. Among the most widely studied are CD44, CD133, ALDH1, and EpCAM [13]. However, these markers are not universal across cancer types, and their expression varies significantly depending on tissue origin and microenvironmental context [2]. This comparative guide provides an objective analysis of these four established and emerging CSC surface markers, presenting experimental data and methodologies to aid researchers in selecting appropriate markers for specific cancer types and research applications.

Marker Comparison Tables

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Established and Emerging CSC Markers

| Marker | Full Name | Primary Function | Common Cancers | Cellular Localization |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD44 | Cluster of Differentiation 44 | Cell surface glycoprotein receptor for hyaluronic acid; involved in cell adhesion, migration, metastasis [16] | Breast, HNSCC, Prostate, Pancreatic [16] | Cell membrane [16] |

| CD133 | Prominin-1 | Pentaspan transmembrane glycoprotein; function not fully understood, associated with stem cell maintenance [15] | NSCLC, Colon, Glioblastoma [15] | Cell membrane protrusions [15] |

| ALDH1 | Aldehyde Dehydrogenase 1 | Cytosolic enzyme; oxidizes retinol to retinoic acid in early stem cell differentiation [16] | Breast, HNSCC, Lung, Pancreatic [16] [17] | Cytoplasm [16] |

| EpCAM | Epithelial Cell Adhesion Molecule | Calcium-independent epithelial cell adhesion molecule [2] | Prostate, Colorectal, Pancreatic [2] | Cell membrane [2] |

Table 2: Prognostic Value and Experimental Detection Methods

| Marker | Prognostic Value | Key Experimental Assays | Detection Reagents |

|---|---|---|---|

| CD44 | Independent prognostic factor for PFS and OS in breast cancer; higher expression in triple-negative vs luminal subtypes [18] | Flow cytometry, IHC, serum ELISA [16] [18] | Anti-CD44 antibodies (Biogenex DF1485) [16] |

| CD133 | Limited prognostic value in NSCLC; glycosylation-specific epitopes (AC133) may be more relevant [15] | Flow cytometry, IHC, lectin-based glycosylation detection [15] | Anti-CD133-APC antibodies (Beckman Coulter C15190) [15] |

| ALDH1 | Correlates with poor prognosis in HNSCC; higher expression in dysplastic OPMDs and OSCC [16] | Aldefluor assay, IHC, flow cytometry [16] [13] | Anti-ALDH1A1 antibodies (Bio SB Clone EP168) [16] |

| EpCAM | Target for CAR-T therapy in prostate cancer; demonstrated effectiveness in preclinical models [2] | Flow cytometry, IHC, CAR-T functional assays [2] | Anti-EpCAM-APC antibodies (Miltenyi 130-109-764) [15] |

Table 3: Functional Roles in Cancer Progression

| Marker | Role in Tumorigenesis | Role in Metastasis | Therapeutic Resistance Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|---|

| CD44 | High CD44/CD24 ratio correlates with strong proliferative capacity and tumorigenicity [17] | CD44 staining index higher in OSCC without lymph node metastasis [16] | Enhances drug efflux, DNA repair capacity, and interaction with tumor microenvironment [11] |

| CD133 | Putative role in tumor initiation; expression associated with tumorigenic capacity [15] | Contributes to metastatic potential through glycosylation patterns [15] | Associated with resistance to conventional chemotherapy in NSCLC [15] |

| ALDH1 | ALDH1+ population indicates malignancy but less directly linked to tumorigenesis than CD44 [17] | Stronger indicator for cell migration and metastasis than CD44 [17] | Detoxifies chemotherapeutic agents; mediates resistance via ALDH1 activity [11] |

| EpCAM | Contributes to tumor initiation through cell adhesion and signaling pathways [2] | Facilitates metastatic spread through epithelial cell adhesion mechanisms [2] | Not well-characterized for therapeutic resistance specifically |

Experimental Protocols for CSC Marker Analysis

Flow Cytometry and Cell Sorting

Protocol Purpose: Isolation and quantification of CSC subpopulations based on surface marker expression.

Workflow Description: The process begins with creating a single-cell suspension from cultured cells or dissociated tumor tissue. Cells are then incubated with fluorescently-conjugated antibodies targeting specific CSC markers (e.g., anti-CD44-APC, anti-CD133-APC). For ALDH1 detection, the Aldefluor assay is employed, where cells are incubated with a fluorescent ALDH substrate. Viable cells are selected by excluding dead cells with propidium iodide staining. Finally, analysis and sorting are performed using instruments like BD FACSAria III cell sorters, with data analysis conducted using specialized software such as Kaluza [15] [13].

Immunohistochemical Staining

Protocol Purpose: Detection of CSC markers in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue sections.

Detailed Methodology:

- Sectioning: Cut 3-4 μm sections from FFPE tissue blocks and mount on silane-coated slides.

- Deparaffinization: Bake slides at 56°C for 2 hours, followed by dewaxing in xylene and rehydration through graded alcohol series.

- Antigen Retrieval: Perform heat-induced epitope retrieval using 10 mM citrate buffer (pH 6) in an autoclave at 121°C for 30 minutes.

- Blocking: Block endogenous peroxidase activity with 3% hydrogen peroxide for 10 minutes.

- Primary Antibody Incubation: Apply prediluted primary antibodies (CD44, ALDH1A1, etc.) for 60 minutes in a humidifying chamber.

- Detection: Incubate with appropriate secondary antibodies followed by 3,3'-diaminobenzidine-tetrahydrochloride (DAB) chromogen substrate.

- Counterstaining: Counterstain with Mayer's hematoxylin for 3 minutes, then mount and evaluate under microscopy [16].

Functional Assessment: Clonogenic Assay

Protocol Purpose: Evaluation of self-renewal capacity of sorted CSC populations.

Method Details: After sorting based on marker expression, seed cells in ultra-low attachment 96-well plates at decreasing cell densities (1000, 100, 10, and 1 cell per well) in defined serum-free medium. Culture for 4-8 weeks, adding 50 μL of fresh medium weekly. Quantify sphere formation per well using optical microscopy, imaging spheroids every 7 days. Measure spheroid size using ImageJ software to assess self-renewal capacity [15].

CSC Marker Signaling Pathways

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for CSC Marker Studies

| Reagent Type | Specific Examples | Application | Experimental Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | Anti-CD44 (Biogenex DF1485), Anti-ALDH1A1 (Bio SB Clone EP168), Anti-CD133-APC (Beckman Coulter C15190), Anti-EpCAM-APC (Miltenyi 130-109-764) [15] [16] | IHC, Flow Cytometry | Specific detection and isolation of CSC subpopulations |

| Cell Sorting Kits | CELLection Biotin Binder Kit (Invitrogen-ThermoFisher) [15] | Magnetic Cell Sorting | Isolation of marker-specific cell populations using magnetic separation |

| Detection Assays | Aldefluor Kit (StemCell Technologies) [13] | ALDH Activity Detection | Functional assessment of ALDH enzyme activity in live cells |

| Cell Culture Supplies | Ultra-low attachment plates (Falcon Corning), Defined serum-free medium [15] | Spheroid Formation Assays | Assessment of self-renewal capacity under non-adherent conditions |

Discussion

Comparative Analysis of Marker Utility

The established and emerging CSC markers present distinct advantages and limitations across different cancer types. CD44 demonstrates significant prognostic value, particularly in breast cancer, where high serum levels correlate with aggressive subtypes and poorer outcomes [18]. Its role in tumorigenesis appears more pronounced than in metastasis, as evidenced by higher CD44 staining indices in OSCC without lymph node metastasis [16].

CD133, while historically important in CSC research, shows limitations in prognostic value for NSCLC, prompting investigations into glycosylation-specific epitopes that may offer greater clinical relevance [15]. The AC133 epitope, selectively expressed in CSCs but masked in differentiated tumor cells, represents a promising direction for improved detection specificity [15].

ALDH1 serves as a functional marker with particular strength in identifying metastatic potential. Research indicates it may be a stronger indicator for cell migration and metastasis than CD44, though its role in tumorigenesis appears less direct [17]. In head and neck cancers, ALDH1 shows promise as a specific marker for dysplasia and malignant progression [16].

EpCAM has emerged as a valuable target for therapeutic applications, particularly in CAR-T cell approaches for prostate cancer [2]. Its role in cell adhesion mechanisms makes it particularly relevant for understanding metastatic spread.

Emerging Approaches and Research Directions

Current challenges in CSC marker research include the lack of universal biomarkers, dynamic plasticity of CSCs, and context-dependent expression patterns [2]. Emerging technologies are addressing these limitations through several innovative approaches:

Glycosylation-Based Detection: Novel methodologies using lectin combinations (UEA-1 and GSL-I) that recognize specific CSC glycan patterns show promise for improved specificity over conventional markers like CD133. This approach has demonstrated prognostic value for overall survival in early-stage NSCLC patients [15].

Multi-Marker Strategies: Research indicates that combining markers (e.g., high CD44/CD24 ratio with ALDH1+) provides more reliable CSC characterization than single markers alone [17]. This approach accounts for the heterogeneity and plasticity of CSC populations.

Advanced Detection Platforms: Cutting-edge technologies including single-cell sequencing, spatial transcriptomics, and AI-driven multiomics analysis are refining CSC characterization and enabling precision medicine applications [2] [13]. Circulating tumor cell analysis and liquid biopsy approaches are also being explored for non-invasive CSC monitoring [18].

The continued refinement of CSC surface markers and detection methodologies remains crucial for advancing our understanding of cancer biology and developing targeted therapeutic strategies to overcome treatment resistance and improve patient outcomes.

The Impact of CSC Plasticity and Dynamic Phenotypic States on Biomarker Stability

The cancer stem cell (CSC) hypothesis has revolutionized our understanding of tumorigenesis, positioning a small subpopulation of cells with self-renewal capacity as the primary drivers of tumor initiation, progression, metastasis, and therapeutic resistance [2] [19]. The reliable identification and targeting of CSCs have consequently emerged as paramount goals in oncology research. This pursuit heavily depends on CSC biomarkers—specific surface proteins, enzymatic activities, and molecular signatures that enable the isolation and study of these cells [20] [13].

However, a fundamental complication arises from the intrinsic plasticity of CSCs—their ability to dynamically switch between phenotypic states in response to environmental cues, therapeutic pressure, and interactions with the tumor microenvironment (TME) [21] [12]. This plasticity challenges the very concept of a stable biomarker, as the molecular identity of CSCs is not fixed but is instead a fluid and context-dependent property [2] [22]. This review objectively compares the stability and reliability of established and emerging CSC biomarkers across different cancer types, framing this analysis within the broader thesis of validating CSC biomarkers for clinical application. We synthesize experimental data to elucidate how phenotypic plasticity directly impacts biomarker expression, with critical implications for diagnostic accuracy, therapeutic targeting, and drug development.

Comparative Analysis of Established CSC Biomarker Stability

The stability of traditional CSC biomarkers is not absolute but varies significantly across cancer types and under different selective pressures. The table below summarizes the stability profiles of key biomarkers based on current experimental evidence.

Table 1: Stability Profile of Established CSC Biomarkers Across Cancer Types

| Biomarker | Primary Cancer Types | Reported Stability | Key Influencing Factors | Functional Role |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD44 | Breast, Pancreatic, Prostate, Colorectal, HNSCC [20] [13] | Moderate-High (but functionally heterogeneous) | Hypoxia, TGF-β signaling, HA-rich niche [13] | Cell adhesion, migration, hyaluronan binding, pro-survival signaling [20] |

| CD133 (Prominin-1) | Glioblastoma, Colon, Pancreatic, Breast [20] | Low-Moderate (highly dynamic) | Chemotherapy, tumor dissociation, metabolic stress [12] [20] | Membrane protrusion organization, cholesterol interaction [20] |

| ALDH1 | Breast, Lung, Ovarian, Bladder [13] | Moderate (functional activity) | Retinoic acid signaling, oxidative stress, chemotherapy [13] [19] | Detoxifying enzyme, retinoic acid metabolism, oxidative stress response [13] |

| EpCAM | Prostate, Colorectal, Pancreatic [2] [13] | High (but subject to cleavage) | EMT, inflammatory cytokines [2] | Cell adhesion, proliferation, and migration signaling [2] |

| CD90 (Thy-1) | Liver, Brain, Colorectal, TNBC [20] | Moderate | β3 integrin, AMPK/mTOR signaling [20] | Cell-cell and cell-matrix interactions, potential immune modulatory role [20] |

The data reveals a core dilemma: while biomarkers like CD44 and EpCAM show relatively stable expression, their presence does not always correlate with a functional CSC state due to heterogeneity within the positive population. Conversely, markers like CD133 exhibit significant dynamism, where their expression can be rapidly induced or lost, making them unreliable for tracking CSCs over time or after therapy [12] [20].

Experimental Dissection of Biomarker Dynamics: Methodologies and Data

Understanding the factors that govern biomarker stability requires sophisticated experimental models that can capture cellular dynamics. The following protocols and resulting data highlight how plasticity directly impacts biomarker readouts.

Experimental Protocol 1: Inducing Plasticity via Therapy Exposure

Objective: To quantify changes in canonical CSC biomarker expression in response to conventional chemotherapy. Methodology:

- Cell Model: Patient-derived organoids (PDOs) from triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) or pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) [12] [13].

- Treatment Regimen: Organoids are treated with a clinically relevant dose of gemcitabine (for PDAC) or paclitaxel (for TNBC) for 72 hours. A control group is maintained in parallel with vehicle treatment [21].

- Analysis:

- Flow Cytometry: Pre- and post-treatment cells are stained for CD44, CD24, CD133, and ALDH1 (via Aldefluor assay). The frequency of marker-positive populations (e.g., CD44+CD24–, CD133+, ALDH1high) is quantified [13].

- Functional Validation: Sorted populations pre- and post-therapy are subjected to in vivo limiting dilution assays in immunocompromised mice to measure tumor-initiating cell (TIC) frequency [13].

- Single-Cell RNA Sequencing (scRNA-seq): A subset of cells is processed for scRNA-seq to profile transcriptomic changes associated with therapy resistance and state transitions [12].

Hypothetical Data & Interpretation: Table 2: Biomarker Flux in PDAC Organoids Post-Gemcitabine Treatment

| Cell Population | Pre-Treatment Frequency (%) | Post-Treatment Frequency (%) | Fold Change in TIC Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|

| CD133+ | 2.1 ± 0.5 | 8.5 ± 1.2 | 4.8x |

| ALDH1high | 3.5 ± 0.7 | 12.3 ± 2.1 | 6.2x |

| CD44+CD24– | 1.8 ± 0.4 | 4.2 ± 0.9 | 3.5x |

| Double Negative (CD133–ALDH1low) | 92.6 ± 3.1 | 74.9 ± 5.4 | 1.0x (reference) |

This data would demonstrate that conventional therapy enriches for populations with high CSC biomarker expression and, more importantly, a functionally validated increase in tumor-initiating capacity. It indicates that biomarker expression can be induced in previously negative or low-expressing cells, a direct result of cellular plasticity [21] [12].

Experimental Protocol 2: Tracking State Transitions via EMT Induction

Objective: To map the relationship between epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), a key plasticity program, and the stability of CSC biomarkers. Methodology:

- Induction System: Use a TGF-β-based in vitro model to induce EMT in a panel of epithelial cancer cell lines (e.g., from breast, lung) [21].

- Longitudinal Monitoring: Employ live-cell imaging of reporters for EMT transcription factors (e.g., Twist, Snail) and surface biomarkers (e.g., CD44-GFP, CD133-RFP) [21] [22].

- Multi-Omic Analysis: Perform scRNA-seq and ATAC-seq (Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin with high-throughput sequencing) on cells at different stages of EMT to correlate chromatin accessibility with gene expression of CSC biomarkers [12].

- Functional Assays: At each time point, cells are assessed for sphere-forming capacity in vitro and tumorigenicity in vivo.

Hypothetical Data & Interpretation: The data would likely show a heterogeneous and transient response to TGF-β. A subset of cells would successfully undergo a full EMT, characterized by downregulation of epithelial markers (E-cadherin) and upregulation of mesenchymal markers (vimentin, N-cadherin). This transition would be temporally correlated with a gradual upregulation of CD44 and induction of CD133, while other markers like EpCAM may be downregulated. scRNA-seq would reveal distinct clusters along the EMT spectrum, with the "partial EMT" or "hybrid E/M" state showing the highest expression of a core stemness signature and the greatest sphere-forming efficiency, supporting the model that plasticity, not a fixed state, underpins the CSC phenotype [21] [12].

Molecular Mechanisms Linking Plasticity to Biomarker Instability

The experimental data on biomarker dynamism can be explained by several underlying molecular mechanisms. The following diagram synthesizes these pathways into a unified model of regulation.

Diagram 1: Mechanisms of biomarker instability. Extrinsic drivers rewire intrinsic molecular pathways, leading to unstable biomarker output and functional adaptation. TME: Tumor Microenvironment.

Epigenetic Reprogramming

CSCs exhibit extensive epigenetic plasticity that allows for rapid, reversible changes in gene expression without altering the DNA sequence. Hypoxia, a common feature of the TME, induces DNA methylation and histone modification changes that promote the expression of stemness genes like OCT4, SOX2, and NANOG, while simultaneously influencing the expression of surface markers like CD44 and CD133 [21] [19]. This reprogramming enables CSCs to adapt their molecular phenotype to survive stress, directly contributing to the transient nature of biomarker-based identification.

Alternative Splicing

Alternative splicing (AS) is a potent and rapid mechanism for proteome diversification. Dysregulation of splicing factors (e.g., SRSF1, SRSF3, hnRNPA1) is a common feature in cancer that drives plasticity [22]. For instance, splicing switches can generate isoforms of receptors and signaling molecules that promote a stem-like state. The expression of these splicing factors themselves is often altered by therapeutic stress or microenvironmental cues, creating a direct link between external pressures and the internal generation of CSC-associated protein variants, thereby destabilizing the definition of a "marker" [22].

Signaling Pathway Crosstalk

The core stemness-associated pathways—Wnt/β-catenin, Notch, and Hedgehog—are not isolated but engage in extensive crosstalk with each other and with pathways activated by the TME (e.g., TGF-β, JAK/STAT) [13] [19]. This integrated signaling network regulates the expression of CSC biomarkers. For example, Wnt signaling can directly transcriptionally activate CD44 expression, while Notch signaling can modulate the expression of CD133. The dynamic activity of these pathways in response to fluctuating signals ensures that biomarker expression remains a fluid readout of cellular state [2] [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Studying CSC Plasticity

Investigating the unstable nature of CSC biomarkers requires a specific set of research tools designed to capture dynamic cellular processes.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for CSC Plasticity and Biomarker Studies

| Reagent / Solution | Function & Utility | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Patient-Derived Organoids (PDOs) | 3D ex vivo models that preserve tumor heterogeneity, TME components, and patient-specific drug responses better than 2D cultures [2] [13]. | Modeling therapy-induced plasticity, longitudinal biomarker tracking, functional validation of TIC frequency. |

| Aldefluor Assay Kit | Fluorescent-based functional assay to detect cells with high aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) enzyme activity, a CSC characteristic in many cancers [13]. | Isolation and analysis of ALDHhigh CSCs, tracking of ALDH1 activity shifts after perturbations. |

| CRISPR/dCas9 Epigenetic Editor Systems | Tools for targeted epigenetic manipulation (e.g., DNA methylation/demethylation, histone acetylation/deacetylation) at specific gene loci [12]. | Causally linking epigenetic changes at biomarker gene promoters to their expression stability and functional stemness. |

| Splicing Factor Inhibitors | Small-molecule inhibitors targeting dysregulated splicing factors (e.g., compounds against SRSF1) [22]. | Probing the role of specific AS events in driving biomarker variability and CSC plasticity. |

| CSC Pathway Modulators | Recombinant proteins (e.g., Wnt3a, Dll4) and small-molecule inhibitors (e.g., LGK974 for Wnt, GANT61 for Hedgehog) for manipulating core stemness pathways [13] [19]. | Experimentally controlling signaling pathways to observe resultant changes in biomarker expression and functional stemness. |

| Single-Cell Multi-Omic Kits | Commercial kits for parallel scRNA-seq and scATAC-seq from the same single cell, enabling coupled analysis of gene expression and chromatin accessibility [12]. | Deconvoluting heterogeneity, mapping trajectories of state transitions, and identifying regulators of biomarker instability. |

The compelling body of evidence synthesized in this review underscores a paradigm shift: CSC biomarkers are not static identifiers but dynamic outputs of a plastic cellular state. This inherent instability, driven by epigenetic, splicing, and signaling dynamics, poses a significant challenge for the validation of CSC biomarkers across cancer types. Relying on a single, fixed marker for diagnostic or therapeutic purposes is likely to fail, as it captures only a transient snapshot of a highly adaptable system.

The future of CSC research and drug development lies in embracing this complexity. This involves:

- Moving beyond static markers to functional signatures that integrate multiple omics layers (transcriptomic, epigenetic, proteomic) to define the CSC state.

- Utilizing computational tools and AI to analyze single-cell data and predict state transitions, identifying critical windows of vulnerability during phenotypic flipping [23] [12].

- Developing therapeutic combinations that simultaneously target the CSC state itself (e.g., via signaling pathway inhibition) and block the plasticity mechanisms that allow for escape (e.g., epigenetic modulators) [2] [19].

For researchers and drug development professionals, this implies that the next generation of biomarkers and targeted therapies must be designed against a backdrop of cellular dynamism. Success in eradicating CSCs and preventing relapse will depend not on finding a stable target, but on understanding and controlling the very processes that make these cells so notoriously evasive.

CSC-Immune System Crosstalk and Its Implications for Biomarker-Driven Immunotherapy

Cancer stem cells (CSCs) represent a specialized subpopulation of tumor cells with capabilities for self-renewal, differentiation, and tumor initiation, playing crucial roles in driving tumor recurrence, metastasis, and resistance to therapies [24] [25]. The interaction between CSCs and the immune system creates a dynamic microenvironment that profoundly influences therapeutic outcomes. CSCs actively shape an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment (TME) through various mechanisms, including secretion of soluble factors, exosome-mediated communication, and metabolic reprogramming [24] [26]. Conversely, immune cells such as tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), and regulatory T cells (Tregs) reciprocally support CSC stemness and maintenance [27] [6]. Understanding these complex interactions is paramount for developing effective biomarker-driven immunotherapies that can overcome CSC-mediated resistance and achieve durable therapeutic responses.

CSC Biomarkers: Landscape and Validation Across Cancer Types

The reliable identification of CSCs through specific biomarkers forms the foundation for targeted therapeutic approaches. However, the CSC biomarker landscape is marked by significant heterogeneity and contextual specificity.

Table 1: Established CSC Biomarkers Across Different Cancer Types

| Biomarker | Cancer Types | Cellular Localization | Functional Role | Specificity Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD44 | Breast, Colon, Glioblastoma, Prostate, Gastric, HNSCC | Cell Surface | Adhesion receptor, stemness maintenance | Expressed on non-stem cancer cells and healthy cells [25] [28] |

| CD133 | Breast, Liver, Lung, Ovarian, Glioblastoma, Sarcomas | Cell Surface Glycoprotein | Cholesterol binding, tumor initiation | Conserved but not universal across cancers [25] [27] |

| ALDH1 | Breast, Prostate, Colon, Lung, Ovarian | Intracellular Enzyme | Aldehyde dehydrogenase, detoxification | Activity-based marker, shared with normal stem cells [25] |

| ABCB5 | Melanoma | Cell Surface Transporter | Drug efflux, chemoresistance | Melanoma-specific [25] |

| ABCG2 | Lung, Pancreatic, Liver, Breast, Ovarian | Cell Surface Transporter | Multidrug resistance | Shared across multiple CSC types [25] |

| CD34 | Leukemia | Cell Surface | Hematopoietic stem cell marker | Limited to hematopoietic malignancies [25] |

| EpCAM | Prostate, Various Carcinomas | Cell Surface | Epithelial cell adhesion | CSC-specific CAR-T target [2] |

The Biomarker of Cancer Stem Cell Database (BCSCdb) serves as a comprehensive repository that systematically categorizes CSC biomarkers identified through both high-throughput and low-throughput methods [29]. This resource has compiled 171 low-throughput biomarkers validated in primary tissues (clinical biomarkers), 283 high-throughput markers validated by low-throughput methods, and 8,307 high-throughput markers, providing a valuable platform for biomarker validation across different cancer types [29]. Each biomarker in BCSCdb is assigned a confidence score based on experimental validation methods and a global score identifying CSC biomarkers across ten different cancer types, enabling researchers to prioritize targets with the strongest evidence [29].

A significant challenge in CSC biomarker development is the lack of universal specificity. Most identified surface markers are also expressed by non-stem cancer cells or healthy cells, albeit at different abundances [25] [2]. Furthermore, CSC markers exhibit considerable plasticity, with expression patterns shifting in response to environmental cues and therapeutic pressures [6] [12]. This dynamic nature necessitates multimodal biomarker approaches that combine surface markers with functional assays for reliable CSC identification across different cancer contexts.

Mechanisms of CSC-Immune Cell Crosstalk in the Tumor Microenvironment

The bidirectional communication between CSCs and immune cells creates a self-reinforcing immunosuppressive niche that protects CSCs from immune elimination and facilitates tumor progression.

CSC-Mediated Immunosuppression

CSCs employ multiple strategies to actively suppress antitumor immunity. They secrete soluble factors including immunosuppressive cytokines (TGF-β, IL-10), chemokines (CCL2, CCL5), and exosomes carrying bioactive molecules that recruit and reprogram immune cells toward immunosuppressive phenotypes [24] [26]. CSCs also modulate immune checkpoint expression, with elevated levels of PD-L1, B7-H4, B7-H3, CD47, and CD24 being reported across various CSC populations [6]. These checkpoints interact with corresponding receptors on immune cells to directly inhibit cytotoxic functions. Additionally, CSCs downregulate antigen-presentation machinery, particularly MHC class I molecules, reducing their visibility to CD8+ cytotoxic T cells [24] [6].

Immune Cell Regulation of CSC Stemness

Reciprocally, immune cells in the TME provide supportive signals that enhance CSC properties. TAMs promote CSC stemness through secretion of growth factors and cytokines such as IL-6, IL-10, and TGF-β, which activate STAT3 and NF-κB signaling pathways within CSCs [24] [26]. MDSCs contribute to CSC survival by secreting immunosuppressive cytokines (IL-10, TGF-β) and exosomes containing microRNAs (miR-21, miR-210) that enhance CSC self-renewal and chemoresistance [24]. Tregs further promote CSC-mediated tumor progression through cytokine secretion and cell-contact-dependent mechanisms, while CSC-secreted chemokines (CCL1, CCL5) specifically attract Tregs, creating a self-amplifying immunosuppressive loop [24] [28].

Figure 1: Bidirectional Crosstalk Between CSCs and Immune Cells. CSCs and immune cells engage in reciprocal communication through cytokines, chemokines, exosomes, and cell-surface interactions, creating an immunosuppressive niche that supports CSC maintenance and immune evasion.

Signaling Pathways Mediating CSC-Immune Interactions

The interplay between CSCs and immune cells is orchestrated by several critical signaling cascades. Wnt/β-catenin, Notch, Hedgehog, and PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathways have been identified as pivotal regulators of CSC-immune crosstalk [24] [27]. These pathways not only maintain CSC stemness but also influence immune cell function and polarization. For instance, the Wnt/β-catenin pathway in CSCs has been linked to T cell exclusion and resistance to checkpoint inhibitors, while Notch signaling regulates both CSC self-renewal and immune cell differentiation [27]. The plasticity of these interactions is further enhanced by epigenetic reprogramming that allows CSCs to dynamically adapt to immune pressure and therapeutic interventions [6].

Experimental Models and Methodologies for Studying CSC-Immune Interactions

Core Experimental Protocols

Research into CSC-immune interactions employs specialized methodologies that enable functional characterization of these rare cell populations and their immunological properties.

CSC Isolation and Enrichment: CSCs are typically isolated using fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) or magnetic-activated cell sorting (MACS) with surface marker combinations (e.g., CD44+/CD24− for breast CSCs, CD133+ for glioblastoma CSCs) [25] [28]. The Aldefluor assay is commonly employed to identify CSCs with high aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) activity [25]. Functional enrichment through sphere-forming assays under non-adherent, serum-free conditions allows for the propagation of CSCs as tumorspheres that maintain stemness properties [30].

In Vitro Co-culture Systems: Direct and indirect co-culture systems enable the investigation of CSC-immune cell interactions. In direct co-cultures, CSCs and immune cells are cultured together, allowing cell-cell contact, while transwell systems permit the study of paracrine signaling without direct contact [28]. These systems are used to assess immune cell migration, polarization, and cytotoxic activity against CSCs, as well as the effects of immune cells on CSC stemness and proliferation.

In Vivo Tumor Models: Immunocompromised mouse models (e.g., NOD/SCID/IL2Rγnull or NSG mice) support the engraftment of human CSCs and enable the study of tumor initiation and growth [30]. Syngeneic immunocompetent models allow for the investigation of interactions between CSCs and a fully functional immune system. Patient-derived xenograft (PDX) models maintain the original tumor heterogeneity and stromal components, providing a more physiologically relevant context for studying CSC-immune interactions [30].

Single-Cell Multi-Omics Approaches: Advanced single-cell technologies, including scRNA-seq, enable high-resolution profiling of rare CSC populations and their transcriptional states within the TME [12]. Computational methods such as CytoTRACE and StemID leverage single-cell data to infer stemness dynamics and cellular differentiation trajectories, moving beyond static marker-based definitions [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Studying CSC-Immune Interactions

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Functional Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| CSC Surface Markers | Anti-CD44, Anti-CD133, Anti-EPCAM Antibodies | CSC isolation and identification | Flow cytometry, cell sorting, immunohistochemistry |

| Intracellular CSC Markers | ALDH1 Assays (Aldefluor) | CSC functional identification | Detection of ALDH enzyme activity |

| Immune Cell Markers | Anti-CD3, CD11b, CD68, FOXP3 Antibodies | Immune cell profiling | Characterization of tumor-infiltrating immune cells |

| Immune Checkpoint Reagents | Anti-PD-1, PD-L1, CD47 Antibodies | Blockade of immune evasion pathways | Immune checkpoint inhibition studies |

| Cytokine/Chemokine Detection | TGF-β, IL-6, IL-10 ELISA Kits | Soluble factor measurement | Quantification of immunosuppressive mediators |

| Exosome Isolation Kits | Ultracentrifugation, Precipitation Kits | Extracellular vesicle studies | Isolation of CSC-derived exosomes |

| Signaling Pathway Inhibitors | LGK974 (Wnt), DAPT (Notch) | Pathway targeting | Dissection of specific signaling mechanisms |

Emerging Therapeutic Strategies and Clinical Translation

Targeting the interface between CSCs and the immune system represents a promising approach to overcome therapy resistance. Several strategy classes have emerged, with varying degrees of clinical validation.

Table 3: Emerging Therapeutic Strategies Targeting CSC-Immune Crosstalk

| Therapeutic Strategy | Molecular Targets | Mechanism of Action | Clinical Development Status | Representative Agents/Trials |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TAM-targeted Therapies | CSF-1R, CCL2 | Reprogram TAMs to anti-tumor phenotype; reduce CSC niche support | Phase I/II | Pexidartinib (NCT02777710), Emactuzumab [24] |

| MDSC-targeted Strategies | CXCR1/2, STAT3 | Block MDSC recruitment and function; restore T cell activity | Phase I | SX-682 + Pembrolizumab (NCT03161431) [24] |

| Treg Depletion | CCR4, CD25 (IL-2Rα) | Deplete Tregs to relieve immune suppression | Phase II | Mogamulizumab (NCT02946671), Basiliximab [24] |

| CSC-specific Immunotherapies | CD133, EpCAM, ALDH | Target CSC antigens for immune-mediated killing | Phase I | CD133-CAR-T cells (NCT03423992, NCT02541370) [24] [2] |

| CSC Signaling Pathway Inhibitors | Wnt, Notch, Hedgehog pathways | Inhibit CSC self-renewal and reduce immunosuppressive cytokines | Phase I | LGK974 (Wnt inhibitor) + anti-PD-1 (NCT01351103) [24] |

| Metabolic Modulation | Glutaminase, fatty acid metabolism | Disrupt CSC and immune cell metabolic crosstalk | Phase I/II | CB-839 (NCT02771626), CPI-613 (NCT03399396) [24] |

| Epigenetic Therapy Combinations | DNMT, HDAC | Reverse CSC-driven immune suppression and resistance | Phase I | Guadecitabine + Atezolizumab (NCT03250273) [24] |

Figure 2: Multimodal Therapeutic Approach to Target CSC-Immune Crosstalk. Effective strategies combine immunotherapy enhancement, direct CSC targeting, and microenvironment modulation to overcome therapeutic resistance.

The clinical translation of CSC-targeted immunotherapies faces several challenges, including the dynamic plasticity of CSCs, which enables them to adapt to therapeutic pressure by altering biomarker expression and metabolic states [6] [12]. Additionally, the lack of universal CSC-specific biomarkers complicates the precise targeting of CSCs without affecting normal stem cells [25] [2]. The immunosuppressive TME further limits the efficacy of immunotherapies by creating physical and molecular barriers that prevent immune cell infiltration and function [24] [6].

Future directions include the development of integrated therapeutic approaches that simultaneously target multiple aspects of CSC-immune crosstalk. Combination strategies incorporating CSC-directed agents with immune checkpoint blockade, adoptive cell therapies, and microenvironment modulators hold promise for achieving more durable responses [24] [6]. Advances in single-cell technologies, spatial transcriptomics, and computational modeling are enabling more precise characterization of CSC states and their interactions with immune cells, paving the way for personalized biomarker-driven immunotherapy approaches [12].

The intricate crosstalk between CSCs and the immune system represents a critical determinant of therapeutic outcomes in cancer treatment. CSCs employ multiple strategies to evade immune surveillance and create an immunosuppressive niche, while immune cells reciprocally support CSC maintenance and stemness. This bidirectional interaction contributes significantly to therapy resistance and tumor recurrence. Comprehensive understanding of CSC-immune dynamics, coupled with validated biomarkers across cancer types, provides the foundation for developing innovative immunotherapeutic strategies. Future research should focus on leveraging advanced technologies to dissect the spatial and temporal dynamics of these interactions, enabling the design of multimodal therapies that can effectively target CSCs and overcome immunosuppression. The integration of CSC biomarkers into clinical trial designs will be essential for advancing biomarker-driven immunotherapy and achieving lasting therapeutic responses for cancer patients.

Advanced Methodologies for CSC Biomarker Discovery and Functional Validation

Cancer stem cells (CSCs) represent a subpopulation of tumor cells with self-renewal capacity and the ability to drive tumor growth, metastasis, and therapeutic resistance [12] [2]. Their elusive nature and dynamic plasticity have made them a primary focus of cancer research, necessitating advanced technologies for their comprehensive characterization. High-throughput omics technologies have revolutionized our ability to profile CSCs across multiple molecular layers, moving beyond static, marker-based definitions to a dynamic and functional perspective [12]. These approaches enable researchers to dissect CSC heterogeneity, identify novel biomarkers, and uncover therapeutic vulnerabilities that could lead to more effective cancer treatments.

The integration of genomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics provides complementary insights into CSC biology. Genomics identifies hereditary and acquired mutations that confer stem-like properties; transcriptomics reveals gene expression patterns and regulatory networks that maintain stemness; and proteomics characterizes the functional effectors that execute CSC programs including surface markers, signaling molecules, and drug efflux pumps [31] [32]. When applied at single-cell resolution, these technologies can capture the rare and heterogeneous nature of CSC populations that are often obscured in bulk analyses [12] [33]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of current high-throughput omics approaches, their performance characteristics, and experimental protocols for profiling CSCs across different cancer types.

Comparative Performance of Omics Technologies

Table 1: Comparison of High-Throughput Omics Technologies for CSC Profiling

| Technology Type | Molecular Target | Key Platforms | Resolution | Throughput | Primary Applications in CSC Research |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genomics | DNA sequences and variations | NGS, DNBSEQ | Single-nucleotide | High | Identifying mutations in stemness genes (BRCA1/2), clonal evolution [32] |

| Transcriptomics | RNA expression patterns | RNA-Seq, scRNA-seq, Stereo-seq | Single-cell (10-500 nm) | High | CSC subpopulation identification, trajectory inference, stemness scoring [12] [34] |

| Proteomics | Protein abundance and modifications | Mass spectrometry, CITE-seq, RPPA | Single-cell to bulk | Moderate-High | Surface marker validation (CD44, CD133), signaling pathway activity, drug targets [31] [33] |

| Multi-Omics Integration | Multiple molecular layers | CITE-seq, ECCITE-seq, Abseq | Single-cell | High | Comprehensive CSC profiling, biomarker validation, network analysis [33] [35] |

Performance Metrics of Single-Cell Clustering Algorithms Across Omics Types

The computational analysis of omics data, particularly clustering algorithms for cell type identification, shows significant performance variation across different omics modalities. A recent comprehensive benchmark evaluation of 28 clustering algorithms across 10 paired transcriptomic and proteomic datasets revealed distinct performance characteristics.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Top Single-Cell Clustering Algorithms Across Omics Types

| Clustering Algorithm | Transcriptomics Performance (ARI) | Proteomics Performance (ARI) | Computational Efficiency | Robustness to Noise | Recommended Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| scAIDE | High (Ranked 2nd) | Highest (Ranked 1st) | Moderate | High | Cross-omics applications, large datasets [33] |

| scDCC | Highest (Ranked 1st) | High (Ranked 2nd) | Memory-efficient | High | Proteomics-focused studies with limited resources [33] |

| FlowSOM | High (Ranked 3rd) | High (Ranked 3rd) | Fast | Excellent | Rapid screening, quality control [33] |

| CarDEC | High (Ranked 4th) | Moderate (Ranked 16th) | Moderate | Moderate | Transcriptomics-specific analyses [33] |

| PARC | High (Ranked 5th) | Low (Ranked 18th) | Fast | Moderate | Transcriptomics-specific analyses [33] |

The benchmarking study demonstrated that top-performing methods like scAIDE, scDCC, and FlowSOM show consistent performance across both transcriptomic and proteomic data, indicating strong generalization capabilities [33]. However, several algorithms exhibited significant performance disparities between omics types. For instance, CarDEC and PARC ranked highly for transcriptomics but dropped significantly in proteomics performance, highlighting the importance of selecting modality-appropriate computational tools [33].

Experimental Protocols for CSC Omics Profiling

Integrated Multi-Omics Workflow for CSC Biomarker Discovery

Diagram 1: Multi-omics workflow for CSC biomarker discovery

Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Protocol for CSC Identification

Protocol Title: Single-Cell RNA Sequencing for CSC Subpopulation Identification

Sample Preparation:

- Obtain fresh tumor tissues or liquid biopsies and process within 1 hour of collection

- Prepare single-cell suspensions using appropriate dissociation protocols (enzymatic/mechanical)

- Assess cell viability (>90%) using trypan blue or automated cell counters

- For CITE-seq: Stain cells with oligonucleotide-tagged antibodies against surface proteins (CD44, CD133, EpCAM) following manufacturer's recommendations [33]

Library Preparation and Sequencing:

- Use droplet-based single-cell platforms (10X Genomics, DNBelab C) according to manufacturer's protocols

- Target cell recovery: 5,000-10,000 cells per sample for adequate CSC capture (CSCs typically <5% of population) [12]

- For full-length transcriptome analysis: Use platforms like scCYCLONE-seq that integrate microfluidics with nanopore chemistry [34]

- Sequence on high-throughput platforms (DNBSEQ, Illumina) with recommended read depth (50,000 reads/cell)

Computational Analysis:

- Process raw data using standardized pipelines (Cell Ranger, Seurat)

- Perform quality control: Remove cells with <200 genes, >10% mitochondrial reads, or high hemoglobin genes

- Normalize data using SCTransform or similar methods

- Identify highly variable genes (HVGs) - typically 2,000-5,000 genes

- Perform dimensionality reduction (PCA, UMAP) and clustering using high-performing algorithms (scDCC, scAIDE) [33]

- Calculate stemness scores using computational tools (CytoTRACE, StemID, mRNAsi) [12]

- Validate CSC populations through trajectory inference and RNA velocity analysis

Chemical Proteomics Protocol for CSC Surface Marker Validation

Protocol Title: Affinity-Based Chemical Proteomics for CSC Surface Marker Identification

Sample Preparation:

- Culture CSC-enriched populations (via tumorsphere assays or FACS sorting)

- Harvest cells at logarithmic growth phase

- Prepare cell lysates using RIPA buffer with protease and phosphatase inhibitors

- Determine protein concentration using BCA assay

Affinity Enrichment and Target Identification:

- For affinity-based approaches: Immobilize small molecule probes (e.g., CSC-targeting compounds) on sepharose beads

- Incubate cell lysates with immobilized compounds (4°C for 4 hours with gentle rotation)

- Wash beads extensively to remove non-specific binders

- Elute bound proteins using competitive elution or SDS-PAGE loading buffer

- For DARTS (Drug Affinity Responsive Target Stability) approach: Incubate protein extracts with compounds of interest, then digest with pronase at room temperature for 30 minutes [31]

Mass Spectrometry Analysis:

- Digest proteins with trypsin overnight at 37°C

- Desalt peptides using C18 stage tips

- Analyze by LC-ESI-MS/MS using high-resolution mass spectrometers

- Identify proteins using database search engines (MaxQuant, Proteome Discoverer) against human protein databases

- Validate targets through orthogonal methods (western blot, functional assays)

Signaling Pathways in CSC Biology

Diagram 2: Core signaling pathways regulating CSC properties

The molecular pathways governing CSC function represent promising therapeutic targets. Multi-omics approaches have been particularly valuable in mapping these complex networks and identifying key regulatory nodes. Central stemness signaling pathways include JAK/STAT, Wnt/β-catenin, Hedgehog, Notch, and TGF-β, which are aberrantly regulated in CSCs compared to normal stem cells [31]. Topology-based pathway analysis tools like Signaling Pathway Impact Analysis (SPIA) and Drug Efficiency Index (DEI) enable quantitative assessment of pathway activation levels from multi-omics data, facilitating personalized drug ranking [35].

Multi-omics integration has revealed that CSCs exhibit significant metabolic plasticity, allowing them to switch between glycolysis, oxidative phosphorylation, and alternative fuel sources such as glutamine and fatty acids [2]. This adaptability contributes to therapy resistance and is regulated by complex interactions between transcriptional networks, protein signaling, and metabolic enzymes. The integration of DNA methylation data with transcriptomic and proteomic profiles has further illuminated the epigenetic mechanisms that stabilize the CSC state, revealing opportunities for epigenetic therapies [35].

Research Reagent Solutions for CSC Omics Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for High-Throughput CSC Omics Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Products/Platforms | Application in CSC Research | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single-Cell Sequencing Kits | 10X Genomics Chromium, DNBelab C | Single-cell transcriptomics and multi-omics | High cell throughput, compatibility with multiple readouts [34] |

| CSC Surface Marker Antibodies | CD44, CD133, EpCAM, CD24 | FACS sorting and CITE-seq | Validated for specific cancer types, conjugated with oligonucleotides [33] [36] |

| Spatial Transcriptomics | Stereo-seq, Nanostring GeoMx | Spatial mapping of CSC niches | Nanoscale resolution (500nm), large field of view (>160cm²) [34] |

| Pathway Analysis Software | Oncobox, SPIA, DEI | Pathway activation assessment | Topology-based analysis, drug efficiency prediction [35] |

| Multi-Omics Integration Tools | MOFA+, OmicsNet, NetworkAnalyst | Integrated analysis of multiple omics layers | User-friendly interfaces, comprehensive visualization [37] [35] |

High-throughput omics technologies have fundamentally transformed our approach to CSC research, enabling the transition from static marker-based definitions to dynamic, functional characterization of these critical cell populations. The integration of genomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics—particularly at single-cell resolution—provides unprecedented insights into CSC heterogeneity, plasticity, and therapeutic vulnerabilities. As benchmarking studies have revealed, careful selection of computational methods tailored to specific omics modalities is essential for optimal performance in CSC identification and characterization [33].

The continuing evolution of multi-omics technologies, including spatial transcriptomics, chemical proteomics, and artificial intelligence-driven analysis, promises to further accelerate CSC research. These advances are paving the way for novel therapeutic strategies that target CSC plasticity, niche adaptation, and immune evasion mechanisms. Moving forward, the integration of metabolic profiling and functional genomics with established omics approaches will provide a more comprehensive understanding of CSC biology, ultimately leading to more effective therapies that prevent tumor recurrence and improve patient outcomes across diverse cancer types.

Single-Cell RNA Sequencing and Spatial Transcriptomics to Decipher CSC Heterogeneity