Beyond Accuracy: A Comprehensive Framework for Validating Machine Learning Models in Cancer Detection

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical process of validating machine learning (ML) models for cancer detection.

Beyond Accuracy: A Comprehensive Framework for Validating Machine Learning Models in Cancer Detection

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical process of validating machine learning (ML) models for cancer detection. It addresses the journey from foundational principles and data challenges to advanced methodological applications, optimization strategies for robust performance, and rigorous comparative validation. The content synthesizes current research and clinical insights to outline a pathway for transitioning ML models from experimental settings to reliable, real-world clinical tools, emphasizing the importance of generalizability, interpretability, and clinical integration for advancing precision oncology.

The Imperative for Rigorous Validation: Foundations and Challenges in Oncology AI

In oncology, the validation of machine learning (ML) models transcends mere technical performance, representing a rigorous, multi-stage process to ensure models are reliable, equitable, and useful in real-world clinical settings. Clinical prediction models, which provide individualised risk estimates to aid diagnosis and prognosis, are widely developed in oncology [1]. The journey from model development to clinical implementation is fraught with methodological challenges, and a robust validation framework is critical for bridging this gap. This guide defines this framework, comparing key validation metrics and methodologies to equip researchers and drug development professionals with the tools for rigorous model assessment.

The fundamental question precedes development: is a new model necessary? The field often suffers from duplication, with over 900 models for breast cancer decision-making and over 100 for predicting overall survival in gastric cancer [1]. Therefore, the first step in any validation-centric workflow is a systematic review of existing models to critically appraise them and, if appropriate, evaluate and update them before embarking on new development [1].

Core Technical Metrics for Model Validation

Technical validation metrics provide the foundational evidence of a model's predictive accuracy. These metrics are typically evaluated during internal validation and are prerequisites for assessing clinical utility. The table below summarizes the core metrics used in clinical prediction models.

Table 1: Key Technical Validation Metrics for Clinical ML Models

| Metric Category | Specific Metric | Definition and Interpretation | Common Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Discrimination | C-statistic (AUC) | Measures the model's ability to distinguish between patients with and without the outcome. Values range from 0.5 (no discrimination) to 1.0 (perfect discrimination). | Overall assessment of a diagnostic or prognostic model's performance. |

| Calibration | Calibration Slope | Assesses the agreement between predicted probabilities and observed outcomes. A slope of 1 indicates perfect calibration. | Critical for risk stratification; often visualized with calibration plots. |

| Overall Performance | Brier Score | The mean squared difference between predicted probabilities and actual outcomes. Lower scores indicate better accuracy. | Provides a single value to evaluate probabilistic predictions. |

Beyond these standard metrics, comprehensive internal validation using bootstrapping or cross-validation is essential to avoid overfitting and obtain reliable performance estimates [1]. Furthermore, validation must address data-specific complexities such as censored observations, competing risks, or clustering effects, which, if ignored, can produce misleading inferences and limit clinical utility [1].

Beyond Technical Metrics: Assessing Clinical Utility

A model with excellent technical metrics may still fail in clinical practice if it does not improve decision-making. Clinical utility assessment determines whether using the model leads to better patient outcomes or more efficient care compared to standard practice.

The primary method for evaluating clinical utility is decision curve analysis, which calculates the "net benefit" of the model across a range of probability thresholds [1]. This analysis weighs the true positive rate against the false positive rate, quantifying the model's value for making clinical decisions. Engaging end-users—including clinicians, patients, and the public—early in the development process is critical to ensure the model addresses a genuine clinical need, selects meaningful predictors, and aligns with real-world workflows [1]. Their involvement ensures the model's outputs are actionable and relevant to those it is intended to serve.

Experimental Protocols for Model Validation

A standardized experimental protocol is mandatory for trustworthy validation. This begins with protocol development and public registration to reduce transparency risks and methodological inconsistencies [1].

Internal and External Validation Workflow

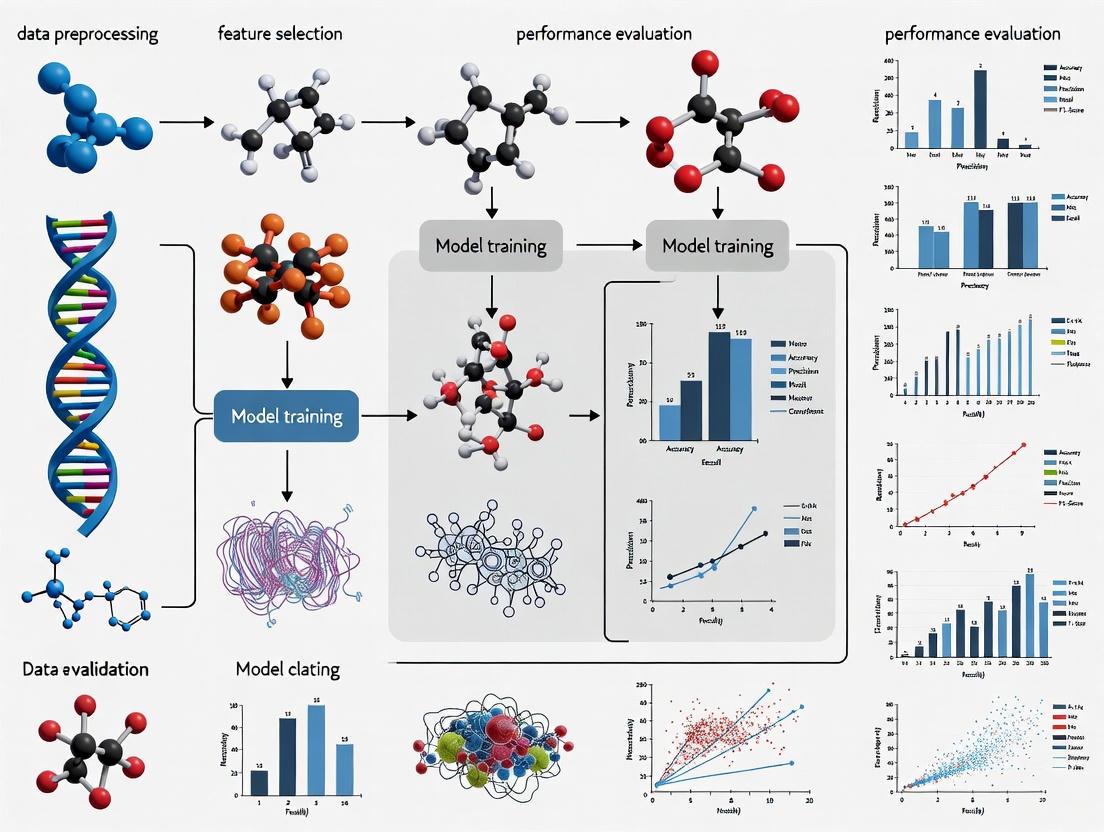

The following diagram illustrates the critical stages of model validation, from initial internal checks to assessing real-world generalizability.

Comparison of Methods Experiment

For validating a new model or test against an existing benchmark, a comparison of methods experiment is standard practice. The protocol involves analyzing a minimum of 40 different patient specimens by both the new (test) method and a established comparative method [2]. These specimens should cover the entire working range of the method and represent the spectrum of diseases expected in routine use. The experiment should be conducted over a minimum of 5 days to capture day-to-day variability, and specimens should be analyzed within two hours of each other to ensure stability [2].

Data analysis should include:

- Graphical Analysis: Creating difference plots (test result minus comparative result) or comparison plots to visually inspect for systematic errors and outliers [2].

- Statistical Calculations: For data covering a wide analytical range, use linear regression to estimate the slope, y-intercept, and standard error about the line (S~y/x~). The systematic error (SE) at a critical medical decision concentration (X~c~) is calculated as SE = Y~c~ - X~c~, where Y~c~ = a + bX~c~ [2].

Quantitative Validation Metrics

Moving beyond graphical comparisons, quantitative validation metrics that incorporate uncertainty are essential. A confidence interval-based approach provides a rigorous statistical method [3]. The core idea is to compute the difference between the computational result (e.g., the model's prediction, S) and the experimentally observed mean (μ~exp~) at a given validation point. The validation metric (ν) is then defined with an associated confidence interval.

The equation for the validation metric is: ν = |S - μ~exp~| ± U~ν~

Where U~ν~ is the uncertainty in the metric, which combines the experimental uncertainty (often a confidence interval based on the t-distribution) and the numerical error in the simulation. This provides a quantitative, probabilistic measure of the agreement between model and reality [3].

A Case Study in AI Agent Validation

A 2025 study in Nature Cancer on an autonomous AI agent for oncology decision-making provides a contemporary template for comprehensive validation [4]. The study developed an AI agent that integrated GPT-4 with specialized precision oncology tools, including vision transformers for detecting genetic alterations from histopathology slides, MedSAM for radiological image segmentation, and search tools like OncoKB and PubMed [4].

Experimental Protocol and Benchmarking

The researchers devised a benchmark of 20 realistic, multimodal patient cases focused on gastrointestinal oncology [4]. For each case, the AI agent autonomously selected and applied relevant tools to derive insights and then used a retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) step to base its responses on medical evidence. Performance was evaluated through a blinded manual review by four human experts, focusing on three areas [4]:

- Tool Use: Accuracy in recognizing and successfully using required tools.

- Output Quality: Completeness and correctness of clinical conclusions and treatment plans.

- Citation Precision: Accuracy in citing relevant oncology guidelines.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Results of the AI Agent [4]

| Evaluation Dimension | Performance Metric | Result | Comparison: GPT-4 Alone |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tool Use | Overall Success Rate | 87.5% (56/64 required tools) | Not Applicable |

| Clinical Conclusions | Correct Treatment Plans | 91.0% of cases | 30.3% |

| Evidence Integration | Accurate Guideline Citations | 75.5% of the time | Not Reported |

| Overall Completeness | Coverage of Expected Statements | 87.2% (95/109 statements) | 30.3% |

This multi-faceted protocol demonstrates a robust framework for validating complex clinical AI systems, moving beyond simple accuracy to assess practical functionality and integration of evidence.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The following table details key resources and tools used in advanced clinical ML validation, as exemplified by the featured case study and general practice.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Clinical ML Validation

| Tool or Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Validation |

|---|---|---|

| OncoKB [4] | Precision Oncology Database | Provides evidence-based information on the clinical implications of genetic variants, used to validate model conclusions against known biomarkers. |

| Vision Transformers [4] | Specialized Deep Learning Model | Detects genetic alterations (e.g., MSI, KRAS, BRAF mutations) directly from histopathology slides, serving as a validated tool for feature extraction. |

| MedSAM [4] | Medical Image Segmentation Model | Segments regions of interest in radiological images (MRI, CT), enabling quantitative measurement of tumor size and growth for response assessment. |

| PubMed / Google Scholar [4] | Scientific Literature Database | Provides access to peer-reviewed literature and clinical guidelines for evidence-based reasoning and citation, grounding model outputs in established science. |

| Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) [4] | AI Technique | Enhances LLM responses by grounding them in a curated repository of medical documents, improving accuracy and providing citable sources. |

| TRIPOD+AI Guideline [1] | Reporting Standard | Ensures transparent and complete reporting of all aspects of model development and validation, facilitating critical appraisal and reproducibility. |

True validation in the clinical context is a continuous journey, not a single event. It begins with robust technical assessment using standardized metrics, extends through rigorous external validation to prove generalizability, and culminates in the demonstration of tangible clinical utility. As the case study shows, even advanced AI systems require integration with specialized tools and evidence bases to achieve clinical-grade accuracy. Finally, overcoming implementation barriers—such as limited stakeholder engagement, workflow integration challenges, and the absence of post-deployment monitoring plans—is essential [1]. Successful clinical translation demands that researchers adopt this comprehensive view of validation, ensuring that models are not only statistically sound but also trustworthy, equitable, and capable of improving patient care.

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) into oncology represents a paradigm shift with transformative potential for cancer diagnosis, treatment selection, and drug development. These technologies demonstrate remarkable capabilities, from classifying cancer types with over 97% accuracy to accelerating drug discovery timelines [5] [6]. However, the deployment of inadequately validated models carries significant risks that extend beyond algorithmic performance metrics to direct patient harm and resource misallocation. Recent evidence indicates substantial deficiencies in methodological and reporting quality within ML studies for cancer applications, with approximately 98% failing to report sample size calculations and 69% neglecting data quality issues [7]. This analysis examines the critical consequences of poor model validation through comparative performance assessment, detailed experimental methodologies, and standardized reporting frameworks essential for researchers and drug development professionals navigating this evolving landscape.

Comparative Performance of Validated Versus Non-Validated Models

Diagnostic and Detection Performance

Table 1: Performance Comparison of AI Models in Cancer Detection and Diagnosis

| Cancer Type | Modality | Task | Model Type | Performance Metrics | Validation Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colorectal Cancer | Colonoscopy | Malignancy detection | CRCNet (Deep Learning) | Sensitivity: 91.3% vs Human: 83.8% (p<0.001); AUC: 0.882 [8] | External validation across three independent cohorts |

| Osteosarcoma | Histopathological & Clinical Data | Detection and classification | Extra Trees Algorithm | 97.8% AUC; 10ms classification time [5] | Stratified 10-fold cross-validation with hyperparameter optimization |

| Breast Cancer | 2D Mammography | Screening detection | Ensemble of 3 DL models | AUC: 0.889 (UK), 0.810 (US); +9.4% improvement vs radiologists (p<0.001) [8] | External validation on different population datasets |

| Various Cancers | Electronic Health Records | Diagnosis categorization | GPT-4o | Free-text accuracy: 81.9%; F1-score: 71.8 [9] | Expert oncology review with benchmark against specialized BioBERT |

| Cancer Survival | Real-world Data | Survival prediction | Random Survival Forest | C-index performance similar to Cox models (SMD: 0.01, 95% CI: -0.01 to 0.03) [10] | Meta-analysis of 21 studies showing limited validation advantage |

The performance differential between rigorously validated and poorly validated models manifests most significantly in real-world clinical settings. Externally validated models such as CRCNet demonstrate robust performance across diverse patient populations, maintaining sensitivity above 90% when tested across three independent hospital systems [8]. In contrast, models lacking rigorous validation frequently exhibit performance degradation when applied to new populations, as evidenced by the performance drop in breast cancer detection models transitioning from UK to US datasets (AUC decrease from 0.889 to 0.810) [8]. This pattern underscores the critical importance of external validation across diverse demographic and clinical populations.

For survival prediction, a comprehensive meta-analysis of 21 studies revealed that machine learning models showed no superior performance over traditional Cox proportional hazards regression (standardized mean difference in C-index: 0.01, 95% CI: -0.01 to 0.03) [10]. This finding challenges claims of ML superiority in time-to-event prediction and highlights the validation gap between theoretical model performance and clinical application, particularly for high-stakes prognostic assessments that guide treatment intensification or palliative care transitions.

Model Performance in Drug Discovery and Development

Table 2: AI Model Performance in Oncology Drug Discovery Applications

| Application Area | Model/Platform | Key Performance Metrics | Validation Level | Reported Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Target Identification | BenevolentAI | Novel target prediction in glioblastoma [6] | Limited clinical validation | Identification of promising leads for further validation |

| Molecular Design | Insilico Medicine | 18-month preclinical candidate development (vs. 3-6 years traditional) [6] | Early-stage clinical trials | QPCTL inhibitors advancing to oncology pipelines |

| Drug Sensitivity Prediction | DREAM Challenge Multimodal AI | Superior prediction vs. unimodal approaches [11] | Benchmarking on standardized datasets | Consistent outperformance in therapeutic outcome prediction |

| Treatment Response | Pathomic Fusion | Outperformed WHO 2021 classification for risk stratification [11] | Glioma and renal cell carcinoma datasets | Improved risk stratification for treatment planning |

| Clinical Trial Optimization | TRIDENT Model | HR reduction: 0.88-0.56 in non-squamous NSCLC [11] | Phase 3 POSEIDON study data | Identified >50% population obtaining optimal treatment benefit |

AI-driven drug discovery platforms demonstrate accelerated timelines, with companies like Exscientia and Insilico Medicine reporting compound development in 12-18 months compared to traditional 4-5 year timelines [6]. However, the ultimate validation metric—regulatory approval and clinical adoption—remains limited. Early reviews suggest an 80-90% success rate for AI-designed molecules in Phase 1 trials, substantially higher than the industry standard, though the sample size remains limited [11]. This discrepancy between accelerated development and regulatory approval highlights the validation gap between computational prediction and clinical efficacy.

Multimodal AI approaches integrating histology and genomics, such as Pathomic Fusion, demonstrate validated performance superior to World Health Organization 2021 classifications for risk stratification in glioma and clear-cell renal-cell carcinoma [11]. Similarly, the TRIDENT machine learning model, which integrates radiomics, digital pathology, and genomics from the Phase 3 POSEIDON study, identified patient subgroups with significant hazard ratio reductions (0.88-0.56 in non-squamous populations) for metastatic non-small cell lung cancer [11]. These exemplars demonstrate the validation rigor required for clinical implementation in precision oncology.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol for Diagnostic Model Validation

A comprehensive validation framework for cancer diagnostic models requires multiple assessment phases. The following protocol synthesizes methodologies from rigorously validated studies analyzed in this review:

Phase 1: Data Curation and Preprocessing

- Apply data denoising techniques including principal component analysis, mutual information gain, and analysis of variance to address data quality issues [5]

- Implement class balancing through random oversampling and address multicollinearity via principal component analysis [5]

- Establish standardized data formats (HL7 for clinical results, FASTQ for omics data) with detailed metadata annotations covering data provenance, collection methods, and quality metrics [12]

Phase 2: Model Training with Robust Internal Validation

- Utilize repeated stratified 10-fold cross-validation to assess model stability [5]

- Optimize hyperparameters using grid search methodologies with appropriate performance metrics (AUC, sensitivity, specificity) [5]

- Implement ensemble methods such as Cascade Deep Forest models to reduce overfitting and maintain generalizability in data-sparse scenarios [13]

Phase 3: External Validation and Performance Assessment

- Validate model performance on completely independent datasets from different institutions or demographic populations [8]

- Compare model performance against clinical expert benchmarks using predefined statistical superiority or non-inferiority margins [8]

- Assess real-world clinical utility through impact studies measuring changes in diagnostic accuracy, time to diagnosis, or clinical decision-making [7]

Phase 4: Reporting and Transparency Documentation

- Adhere to CONSORT, TRIPOD-AI, and CREMLS reporting guidelines with specific attention to sample size justification, data quality issues, and handling of outliers [7]

- Document model architecture, training parameters, and potential limitations for regulatory review and clinical implementation [13]

Protocol for Predictive Model Validation in Drug Discovery

The validation of AI models for oncology drug discovery requires specialized methodologies to address unique challenges in target identification, compound screening, and clinical trial optimization:

Target Identification and Compound Screening

- Integrate multi-omics data (genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics) using deep learning architectures such as DeepDTA for drug-target interaction prediction [13]

- Employ graph-based neural networks including GraphDTA and Mol2Vec to encode chemical structures as graph embeddings for bioactivity prediction [13]

- Utilize generative adversarial networks (GANs) and variational autoencoders trained on large chemical libraries (ZINC, ChEMBL) for de novo molecular design with optimized ADMET properties [13]

Clinical Trial Optimization and Predictive Biomarker Development

- Implement multimodal AI frameworks such as AstraZeneca's ABACO platform that integrate real-world evidence with explainable AI to identify predictive biomarkers [11]

- Apply natural language processing tools (PubTator, LitCovid) to mine biomedical literature and clinical trial data for hidden associations between drugs, genes, and diseases [13]

- Validate predictive signatures through retrospective analysis of Phase 3 trial data (e.g., TRIDENT analysis of POSEIDON study) before prospective implementation [11]

Transversal Validation Considerations

- Address model interpretability through explainable AI techniques, particularly for "black box" deep learning models requiring regulatory approval [6] [13]

- Assess potential algorithmic bias by evaluating model performance across demographic subgroups and cancer subtypes [7]

- Establish continuous monitoring systems for model performance drift in real-world clinical settings [11]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Oncology AI Validation

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Validation Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Specialized AI Models | BioBERT, DeepDTA, Cascade Deep Forest | Domain-specific model architectures | Enhanced performance on biomedical data through specialized training |

| Data Processing Frameworks | Principal Component Analysis, Mutual Information Gain, Analysis of Variance | Data denoising and feature selection | Address data quality issues and reduce dimensionality for improved generalizability |

| Model Training Platforms | MONAI, PyTorch, TensorFlow | Deep learning framework with medical imaging focus | Standardized implementation and reproducibility of model architectures |

| Validation Datasets | The Cancer Genome Atlas, SEER Database, OMI-DB | Large-scale standardized oncology datasets | External validation benchmark across diverse patient populations |

| Explainability Tools | SHAP, LIME, Attention Mechanisms | Model interpretability and feature importance | Regulatory compliance and clinical trust through transparent decision-making |

| Federated Learning Infrastructure | NVIDIA FLARE, OpenFL | Privacy-preserving collaborative learning | Multi-institutional validation without data sharing constraints |

The selection of appropriate research reagents and computational tools fundamentally influences validation outcomes. Specialized domain-specific models such as BioBERT, which is pretrained on biomedical corpora, demonstrate superior performance in categorizing cancer diagnoses from electronic health records compared to general-purpose large language models, achieving weighted macro F1-scores of 84.2 for structured ICD code classification [9]. This performance advantage highlights the importance of domain-adapted architectures for clinically relevant tasks.

Federated learning infrastructure represents a critical advancement for validation across institutions while addressing data privacy constraints. This approach enables model training and validation across multiple healthcare systems without sharing raw patient data, enhancing the diversity and representativeness of validation cohorts while maintaining compliance with regulations such as HIPAA and GDPR [12]. Similarly, standardized medical imaging frameworks like MONAI provide pre-trained models and specialized processing layers for consistent evaluation across different imaging modalities and devices [11].

Consequences of Inadequate Validation

Direct Patient Harms

Poorly validated models precipitate cascading failures throughout the clinical oncology pathway. In diagnostic applications, validation deficiencies manifest as differential performance across demographic groups, potentially exacerbating healthcare disparities. For instance, breast cancer screening models demonstrating strong performance in UK populations (AUC: 0.889) showed significantly reduced accuracy when applied to US datasets (AUC: 0.810), highlighting the potential for systematic diagnostic errors in different healthcare contexts [8]. Such performance variations risk both false negatives delaying critical interventions and false positives leading to unnecessary invasive procedures, psychological distress, and radiation exposure from follow-up imaging.

In treatment selection, inadequately validated predictive models for therapy response can direct patients toward ineffective treatments while delaying more appropriate alternatives. For example, models predicting immunotherapy response without proper validation across different cancer subtypes may fail to identify nuanced biomarkers of resistance, resulting in treatment failure and unnecessary toxicity [6] [11]. The integration of AI-derived biomarkers into clinical decision-making necessitates validation rigor comparable to traditional laboratory-developed tests, particularly for high-stakes treatment decisions in advanced malignancies.

Resource and Economic Impacts

The resource implications of poorly validated oncology AI models extend across the healthcare ecosystem. At the institutional level, implementation of under-validated systems incurs substantial infrastructure costs without demonstrating clear clinical benefit, potentially diverting resources from proven interventions. In drug development, AI-platforms claiming accelerated discovery timelines require validation against the ultimate endpoint of regulatory approval and clinical adoption. Early analyses suggest promising trends, with AI-designed molecules potentially progressing to clinical trials at twice the rate of traditionally developed compounds [11]. However, the validation gap between in silico prediction and clinical efficacy remains substantial, with an estimated 90% of oncology drugs still failing during clinical development [6].

The opportunity cost of pursuing AI-derived therapeutic targets without robust validation includes both direct financial expenditure and the diversion of scientific resources from potentially more productive avenues. Conversely, properly validated AI models in clinical trial optimization, such as those enabling synthetic control arms or predictive enrichment strategies, demonstrate potential to reduce trial costs and accelerate approvals [11]. This dichotomy underscores the economic imperative for rigorous validation frameworks that distinguish clinically viable AI applications from those with only theoretical promise.

Regulatory and Reputational Consequences

The regulatory landscape for AI in oncology remains evolving, with frameworks such as the FDA's Software as a Medical Device (SaMD) classification requiring demonstration of clinical validity and utility [13]. Poorly validated models face increasing regulatory scrutiny, particularly as real-world performance discrepancies emerge post-implementation. The absence of standardized validation methodologies contributes to regulatory uncertainty, potentially delaying beneficial innovations while allowing problematic applications to reach clinical use.

Transparent reporting of model limitations, training data characteristics, and performance boundaries represents a critical component of responsible validation. Current analyses indicate significant deficiencies in ML study reporting, with fewer than 40% adequately describing strategies for handling outliers or data quality issues [7]. These reporting failures impede regulatory evaluation, scientific reproducibility, and clinical trust, ultimately undermining the broader integration of AI methodologies into oncology research and practice.

The integration of AI and ML into oncology presents unprecedented opportunities to address complex challenges in cancer diagnosis, treatment optimization, and therapeutic development. However, the substantial consequences of inadequate validation—including direct patient harm, resource misallocation, and erosion of clinical trust—demand rigorous methodological standards exceeding traditional software validation frameworks. The comparative analyses presented demonstrate that properly validated models maintain performance across diverse populations and clinical settings, while those lacking robust validation frequently fail in translation from development to implementation.

Future advances in oncology AI will require sustained focus on validation methodologies, including standardized protocols for external testing, prospective clinical impact studies, and transparent reporting of limitations and failures. The scientist's toolkit must evolve to include specialized domain-adapted models, privacy-preserving validation infrastructures, and explainability frameworks that bridge the gap between algorithmic prediction and clinical decision-making. Only through this comprehensive validation paradigm can the oncology community fully harness AI's potential while mitigating the substantial risks of premature or inappropriate clinical implementation.

The advancement of machine learning (ML) in oncology presents a critical paradox: models require vast, diverse datasets to achieve high performance and generalizability, yet medical data is often scarce, fragmented across institutions, and governed by stringent privacy regulations. This "data trilemma" creates significant barriers to developing robust models for cancer detection. The scarcity challenge is particularly acute in rare cancers and specific disease subtypes, where limited patient numbers restrict the statistical power of studies [14]. Furthermore, data heterogeneity—variations in collection protocols, equipment, and patient demographics across institutions—hinders the development of models that perform consistently across diverse populations [15] [16]. Compounding these issues, privacy regulations like HIPAA and GDPR rightly restrict data sharing, creating additional friction for collaborative research that could overcome scarcity and heterogeneity [14] [17]. This guide objectively compares emerging technological solutions designed to navigate these challenges, evaluating their experimental performance and methodologies within the context of validating ML models for cancer detection.

Comparative Analysis of Technological Solutions

The following table summarizes three primary technological approaches being developed to address the core challenges in medical data for oncology research.

Table 1: Comparison of Technological Solutions for Medical Data Challenges

| Solution | Primary Addressed Challenge | Core Mechanism | Reported Performance | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Federated Learning (FL) [15] [16] | Data Privacy, Heterogeneity | Decentralized model training; data remains at source | FednnU-Net outperformed local training in multi-institutional segmentation tasks [16] | Complex coordination; sensitive to data heterogeneity |

| Synthetic Data Generation [18] [14] | Data Scarcity, Privacy | AI generates artificial datasets mimicking real data | KNN model achieved 97+% accuracy on synthetic breast cancer data [18] | Risk of capturing or amplifying real-data biases |

| Explainable AI (XAI) & Ensemble Models [18] [19] | Model Validation, Trust | Provides model interpretability; combines multiple models | Random Forest ensemble achieved 84% F1-score in breast cancer prediction [19] | Adds computational overhead; does not solve data access |

Experimental Protocols and Performance Data

Federated Learning in Action: The FednnU-Net Framework

Federated learning has emerged as a leading privacy-preserving approach for multi-institutional collaboration. The FednnU-Net framework provides a specific implementation for medical image segmentation, a critical task in oncology. Its experimental protocol involves a decentralized setup where multiple institutions (clients) collaborate to train a model without sharing their raw data.

- Core Methodology: The framework introduces two key methods to handle dataset heterogeneity across institutions. Federated Fingerprint Extraction (FFE) allows the system to analyze dataset characteristics (like image spacing and voxel size) from all clients to determine a unified training strategy. Asymmetric Federated Averaging (AsymFedAvg) enables the aggregation of model updates from clients even when their model architectures differ slightly, a common occurrence in real-world federated settings [16].

- Experimental Workflow: The process is cyclic: (1) A central server sends a global model to all client institutions. (2) Each client trains the model locally on its own data. (3) Clients send only the model updates (weights) back to the server. (4) The server aggregates these updates using AsymFedAvg to create an improved global model. This cycle repeats, refining the model without data ever leaving the original hospital [16].

- Performance Data: In experiments across six datasets from 18 institutions for breast, cardiac, and fetal segmentation, FednnU-Net consistently outperformed models trained locally at single institutions, demonstrating successful knowledge integration while preserving privacy [16].

The following diagram illustrates the operational workflow and the two novel protocols of the FednnU-Net framework.

Synthetic Data Generation for Augmenting Rare Datasets

Synthetic data generation creates artificial datasets that mimic the statistical properties of real patient data, directly addressing data scarcity and privacy.

- Core Methodology: Several techniques are employed, ranging from statistical models like Gaussian Copula to advanced deep learning models like Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) and Variational Autoencoders (VAEs). For tabular medical data (e.g., patient records), architectures like Conditional Tabular GANs (CTGANs) and Tabular VAEs (TVAE) are particularly relevant [14]. These models learn the underlying distribution, correlations, and patterns from the original dataset and generate new, synthetic samples.

- Experimental Workflow: A typical protocol involves: (1) Using an original, often small, clinical dataset. (2) Training a generative model (e.g., TVAE) on this data. (3) Using the trained model to produce a larger synthetic dataset. (4) Training a downstream ML model (e.g., a classifier) on the synthetic data and evaluating its performance on a held-out set of real data to validate utility [18] [14].

- Performance Data: A 2025 study on breast cancer prediction compared models trained on original versus synthetic data. The K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) model achieved high accuracy on the original dataset, while an AutoML approach (H2OXGBoost) trained on synthetic data generated by Gaussian Copula and TVAE also showed competitively high accuracy, demonstrating synthetic data's potential [18].

Table 2: Breast Cancer Prediction Model Performance on Original vs. Synthetic Data [18]

| Machine Learning Model | Dataset Type | Key Performance Metric | Reported Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) | Original Data | Accuracy | High (Precise figure not stated, "outperformed others") |

| H2O AutoML (XGBoost) | Synthetic Data (Gaussian Copula, TVAE) | Accuracy | High |

| Stacked Ensemble Model | Original Data | F1-Score | 83% |

| Random Forest | Original Data | F1-Score | 84% |

Explainable AI and Ensemble Models for Robust Validation

Beyond data access, ensuring model reliability and trust is crucial for clinical validation. Explainable AI (XAI) and ensemble models address this.

- Core Methodology: Ensemble models, such as stacking multiple algorithms (e.g., SVM, Random Forest, XGBoost), combine the strengths of individual models to improve overall prediction accuracy and stability [18] [19]. Explainable AI (XAI) techniques, including SHAP and LIME, are then used to interpret the model's predictions, identifying which features (e.g., tumor size, involved nodes) were most influential [19].

- Experimental Workflow: Researchers first preprocess data and handle missing values. They then train multiple base classifiers. For an ensemble, a meta-learner is trained on the outputs of these base models. Finally, XAI methods are applied to the final model to interpret its decision-making process, validating that it relies on clinically relevant features [19].

- Performance Data: A 2025 study on breast cancer detection using the UCTH Breast Cancer Dataset found that a Random Forest model achieved an F1-score of 84%, while a custom Stacked Ensemble model achieved 83%. The study used SHAP analysis to validate that features like "Involved nodes," "Tumor size," and "Metastasis" were the top contributors to the model's predictions, aligning with clinical knowledge [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

The following table catalogs key computational tools and frameworks cited in the featured experiments, essential for replicating and advancing this research.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Solutions

| Tool / Solution | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| FednnU-Net [16] | Software Framework | Privacy-preserving, decentralized medical image segmentation | Multi-institutional collaboration without sharing raw data |

| nnU-Net [16] | Software Framework | Automated configuration of segmentation pipelines | Gold-standard baseline for medical image segmentation tasks |

| Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) [14] | AI Model Architecture | Generates synthetic data (images, tabular, genomic) | Data augmentation for rare diseases; creating privacy-safe datasets |

| Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) [14] | AI Model Architecture | Generates synthetic data with probabilistic modeling | Often used with smaller datasets; can be combined with GANs (VAE-GANs) |

| SHAP / LIME [19] | Explainable AI Library | Interprets model predictions to build trust and identify key features | Validating that ML models use clinically relevant features for cancer detection |

| H2O AutoML [18] | Automated ML Platform | Automates the process of training and tuning multiple ML models | Benchmarking and efficiently finding top-performing models for a given dataset |

| Synthetic Data Generators (Gaussian Copula, TVAE) [18] [14] | Data Generation Tool | Creates artificial tabular datasets that mimic real data | Overcoming data scarcity for training and testing ML models |

The validation of machine learning models in cancer detection research is inherently constrained by the available data landscape. No single solution perfectly resolves the tensions between scarcity, heterogeneity, and privacy. Federated learning offers a robust path for privacy-preserving collaboration but requires sophisticated infrastructure. Synthetic data generation effectively mitigates scarcity and privacy concerns but demands rigorous validation to ensure fidelity and fairness. Finally, Explainable AI and ensemble models are indispensable for building reliable, interpretable, and high-performing systems that clinicians can trust. The future of robust oncology AI likely lies in the strategic combination of these approaches, leveraging their complementary strengths to navigate the complex medical data landscape and deliver equitable, impactful tools for cancer care.

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) into clinical oncology offers transformative potential for improving cancer diagnostics, treatment planning, and patient outcomes [20]. However, the proliferation of complex machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) models has brought to the forefront the critical challenge of the "black box" problem—where model decisions are made in an opaque manner that is not easily understood by human experts [21]. This opacity represents a significant barrier to clinical adoption, as healthcare professionals require trust and verifiability when making high-stakes decisions that affect patient lives [22]. The lack of transparency and accountability in predictive models can have severe consequences, including incorrect treatment recommendations and the perpetuation of biases present in training data [22] [23].

Within oncology, where models are increasingly used for early cancer detection, risk stratification, and treatment personalization, the demand for interpretability is not merely academic but ethical and practical [20]. Interpretability serves as a bridge between predictive performance and clinical utility, enabling researchers and clinicians to validate model reasoning, identify potential failures, and ultimately build the trust necessary for integration into healthcare workflows [23]. This review examines the critical role of model interpretability as a foundational prerequisite for clinical trust and adoption, comparing approaches for explaining black-box models with inherently interpretable alternatives within the context of cancer detection research.

Explaining Black Boxes vs. Inherently Interpretable Models: A Fundamental Divide

A fundamental dichotomy exists in approaches to model transparency: creating post-hoc explanations for black-box models versus designing models that are inherently interpretable from their inception [22]. This distinction carries significant implications for clinical validation and trust.

Black-box models, such as deep neural networks and complex ensemble methods, operate as opaque systems where internal workings are not easily accessible or interpretable [21]. While these models can achieve high predictive performance, their decision-making process remains hidden, requiring secondary "explainable AI" (XAI) techniques to generate post-hoc rationales for their predictions [22] [21]. In contrast, inherently interpretable models are constrained in their form to be transparent by design, providing explanations that are faithful to what the model actually computes [22]. These include sparse linear models, decision lists, and models that obey structural domain knowledge such as monotonicity constraints (e.g., ensuring that the risk of cancer increases with age, all else being equal) [22].

A critical misconception in the field is the presumed necessity of a trade-off between accuracy and interpretability [22]. In many applications with structured data and meaningful features, there is often no significant difference in performance between complex black-box classifiers and much simpler interpretable models [22]. The ability to interpret results can actually lead to better overall accuracy through improved data processing and feature engineering in subsequent iterations of the knowledge discovery process [22].

Table 1: Comparison of Interpretability Approaches in Machine Learning

| Characteristic | Post-hoc Explainable AI (XAI) | Inherently Interpretable Models |

|---|---|---|

| Explanation Fidelity | Approximate; may not perfectly represent the black box's true reasoning [22] | Exact and faithful to the model's actual computations [22] |

| Model Examples | LIME, SHAP, attention mechanisms [21] | Sparse linear models, decision lists, generalized additive models [22] |

| Clinical Trust | Limited by potential explanation inaccuracies in critical regions of feature space [22] | Higher potential due to transparent reasoning process [22] |

| Typical Use Cases | Explaining pre-existing complex models (DNNs, random forests) [21] | New model development for high-stakes decision domains [22] |

| Regulatory Considerations | Challenging to validate due to separation of model and explanation [22] | Potentially simpler validation pathway due to integrated transparency [22] |

Interpretability Frameworks and Methodologies

The field of explainable AI has developed numerous technical approaches to address the black box problem, which can be broadly categorized into model-specific and model-agnostic methods, as well as global and local explanation techniques [21].

Model-Agnostic Interpretation Methods

Model-agnostic methods can be applied to any machine learning model after it has been trained, making them particularly valuable for explaining complex black-box models already in use in clinical settings. One prominent example is SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP), which connects game theory with local explanations to quantify the contribution of each feature to a individual prediction [21] [24]. For example, in a study predicting delays in seeking medical care among breast cancer patients, researchers used SHAP to provide model visualization and interpretation, identifying key factors influencing predictions [24]. Similarly, LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations) approximates black-box models locally with interpretable models to create explanations for individual instances [21].

inherently Interpretable Model Architectures

Inherently interpretable models avoid the fidelity issues of post-hoc explanations by design. These models include:

- Sparse linear models: These constrain the number of features used, making it easier for humans to comprehend the relationships since people can handle at most 7±2 cognitive entities at once [22].

- Decision lists and rules: These provide explicit, logical conditions that lead to specific predictions, mirroring clinical decision-making processes.

- Monotonic models: These enforce directional constraints (e.g., risk increases with age) that align with clinical domain knowledge [22].

- Generalized additive models (GAMs): These provide transparent structure while capturing nonlinear relationships [22].

Table 2: Experimental Metrics for Evaluating Interpretability Methods in Cancer Prediction

| Evaluation Metric | Description | Application in Cancer Research |

|---|---|---|

| Prediction Accuracy | Standard measures of model predictive performance (AUC, F1-score, etc.) | CatBoost achieved 98.75% accuracy in cancer risk prediction [25]; RF showed AUC of 0.86 in predicting care delays [24] |

| Explanation Faithfulness | Degree to which explanations accurately represent the model's actual reasoning process [22] | Critical for clinical validation; post-hoc explanations necessarily have imperfect fidelity [22] |

| Human Interpretability | Assessment of how easily domain experts can understand the explanation | Sparse models allow view of how variables interact jointly rather than individually [22] |

| Robustness | Consistency of explanations for similar inputs | Essential for clinical reliability; small changes in input shouldn't cause large explanation changes [23] |

| Bias Detection | Ability to identify discriminatory patterns or unfair treatment of subgroups | Interpretable models can be audited to ensure they don't discriminate based on demographics [23] |

Experimental Protocols for Interpretability Validation in Cancer Detection

Validating interpretability methods requires rigorous experimental protocols that assess both explanatory power and predictive performance. The following methodologies represent current approaches in cancer detection research.

Model Development and Interpretation Workflow

The experimental workflow for developing and interpreting machine learning models in cancer research typically follows a structured pipeline that integrates both performance optimization and explanation generation, as exemplified by recent studies in cancer risk prediction [25] and care delay prediction [24].

Case Study: Predicting Delays in Breast Cancer Care

A 2025 study on predicting delays in seeking medical care among breast cancer patients in China provides a representative experimental protocol for interpretable machine learning in oncology [24]:

Dataset and Preprocessing: The study utilized a cross-sectional methodology collecting demographic and clinical characteristics from 540 patients with breast cancer. Of these, 212 patients (39.26%) experienced a delay in seeking care, creating a balanced classification scenario [24].

Feature Selection: Feature selection was performed using a Lasso algorithm, which identified eight variables most predictive of care delays. This sparse feature selection enhances interpretability by focusing on the most clinically relevant factors [24].

Model Training and Comparison: Six machine learning algorithms were applied for model construction: XGBoost (XGB), Logistic Regression (LR), Random Forest (RF), Complement Naive Bayes (CNB), Support Vector Machines (SVM), and K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN). The k-fold cross-validation method was used for internal verification [24].

Model Evaluation: Multiple evaluation approaches were employed:

- ROC curves assessed discrimination capability

- Calibration curves evaluated prediction accuracy

- Decision Curve Analysis (DCA) quantified clinical utility

- External validation tested generalizability [24]

Interpretation and Visualization: The SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) method was used for model interpretation and visualization, providing both global and local explanations of model behavior [24].

Results: The Random Forest model demonstrated superior performance with AUC values of 1.00, 0.86, and 0.76 in the training set, validation set, and external verification respectively. The calibration curves closely resembled ideal curves, and DCA showed net clinical benefit [24].

Case Study: Cancer Risk Prediction Using Lifestyle and Genetic Data

A 2025 study on cancer risk prediction provides another exemplar of interpretable ML protocols in oncology research [25]:

Dataset: The study used a structured dataset of 1,200 patient records with features including age, gender, BMI, smoking status, alcohol intake, physical activity, genetic risk level, and personal history of cancer [25].

Model Comparison: Nine supervised learning algorithms were evaluated and compared: Logistic Regression, Decision Tree, Random Forest, Support Vector Machines, and several ensemble methods [25].

Performance Assessment: The models were evaluated using stratified cross-validation and a separate test set. Categorical Boosting (CatBoost) achieved the highest predictive performance with a test accuracy of 98.75% and an F1-score of 0.9820 [25].

Feature Importance Analysis: The study conducted feature importance analysis, which confirmed the strong influence of cancer history, genetic risk, and smoking status on prediction outcomes, providing clinical face validity to the model [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents for Interpretable AI in Cancer Research

The implementation and validation of interpretable machine learning models in cancer detection requires a suite of methodological tools and software frameworks.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Interpretable AI in Cancer Research

| Tool/Reagent | Type | Function in Interpretable AI Research |

|---|---|---|

| SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) | Software Library | Explains output of any ML model by quantifying feature importance for individual predictions [21] [24] |

| LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations) | Software Library | Creates local surrogate models to explain individual predictions of black box models [21] |

| Lasso Regression | Algorithm | Performs feature selection for sparse, interpretable models by penalizing non-essential coefficients [24] |

| Random Forest | Algorithm | Provides inherent feature importance metrics while maintaining high performance in medical applications [24] [25] |

| CatBoost | Algorithm | Gradient boosting implementation with built-in feature importance analysis and high predictive accuracy [25] |

| Stratified Cross-Validation | Methodological Protocol | Ensures reliable performance estimation across data subsets, critical for clinical validation [24] [25] |

| Decision Curve Analysis (DCA) | Statistical Method | Evaluates clinical utility of models by quantifying net benefit across threshold probabilities [24] |

| ROC/AUC Analysis | Evaluation Metric | Measures discriminatory capability of models using receiver operating characteristic curves and area under curve [24] [25] |

The black box problem in machine learning represents a critical challenge for clinical adoption in oncology, where decisions directly impact patient outcomes and require rigorous validation [22] [20]. While post-hoc explanation methods like SHAP and LIME provide valuable tools for interpreting existing complex models, inherently interpretable models offer distinct advantages for high-stakes medical applications through their guaranteed explanation fidelity and alignment with clinical reasoning patterns [22].

The experimental protocols and case studies presented demonstrate that interpretability need not come at the cost of performance, with many studies achieving high predictive accuracy while maintaining model transparency [24] [25]. As AI continues to transform cancer diagnostics and treatment, the research community must prioritize the development and validation of interpretable models that enable clinical experts to understand, trust, and effectively utilize these powerful tools in patient care [22] [20]. Future work should focus on standardizing evaluation metrics for interpretability, developing domain-specific interpretable model architectures, and establishing regulatory frameworks that ensure transparency and accountability in clinical AI systems [20].

The integration of machine learning (ML) models into clinical practice for cancer detection represents a paradigm shift in oncology. However, their path from research validation to clinical deployment is fraught with complex regulatory and ethical challenges. The validation of these models extends beyond mere algorithmic accuracy; it necessitates rigorous adherence to data protection laws like the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) in the U.S. and the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in the EU, as well as medical device regulations enforced by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) [26] [6]. These frameworks collectively aim to ensure that innovative technologies are not only effective but also safe, ethical, and respectful of patient privacy. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the nuances and intersections of these regulations is crucial for designing robust validation protocols and facilitating the successful translation of ML models from the bench to the bedside. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these key regulatory hurdles, supported by experimental data and structured to inform the validation process within cancer detection research.

Comparative Analysis of Key Regulatory Frameworks

HIPAA vs. GDPR: A Privacy-Centric Comparison

For any ML model handling patient data, compliance with data privacy regulations is the first critical hurdle. HIPAA and GDPR are the two most influential frameworks, but they approach data protection with distinct philosophies and requirements.

Table 1: Core Differences Between HIPAA and GDPR in Clinical Research

| Feature | HIPAA (U.S. Focus) | GDPR (EU Focus) |

|---|---|---|

| Scope & Application | Applies to "covered entities" (healthcare providers, plans, clearinghouses) and their "business associates" [27] [28]. | Applies to any organization processing personal data of EU individuals, regardless of location [27] [28]. |

| Data Definition | Protects "Protected Health Information (PHI)" [27]. | Protects "personal data," defined much more broadly to include any information relating to an identified or identifiable person [28]. |

| Legal Basis for Processing | Primarily relies on patient authorization for use/disclosure of PHI [28]. | Offers multiple bases, including explicit consent, legitimate interest, or performance of a task in the public interest [29] [28]. |

| Data Subject Rights | Rights to access, amend, and receive an accounting of disclosures [28]. | Extensive rights including access, rectification, erasure ("right to be forgotten"), and data portability [27] [28]. |

| Data Breach Notification | Required within 60 days of discovery for breaches affecting 500+ individuals [27]. | Mandatory reporting to authorities within 72 hours of becoming aware of the breach [27] [28]. |

| Anonymization | De-identified data (per Safe Harbor or Expert Determination methods) is no longer considered PHI and is exempt [30] [28]. | Pseudonymized data is still considered personal data and remains under GDPR protection [28]. |

| Cross-Border Data Transfer | No specific provisions for international transfers [28]. | Strict rules requiring adequacy decisions or safeguards like Standard Contractual Clauses (SCCs) [28]. |

The implications for ML validation are profound. Under HIPAA, once data is de-identified, it can be used more freely for model training and testing [28]. In contrast, the GDPR's stricter view of pseudonymization means that most data used in ML workflows for cancer research likely remains subject to its requirements, including the principles of data minimization and purpose limitation [29]. This means researchers must justify the amount of data collected and specify its use at the outset, challenging practices where data is repurposed for new ML projects without a fresh legal basis.

FDA Regulatory Pathways for AI/ML-Enabled Medical Devices

In the U.S., ML models intended for clinical use in cancer detection, diagnosis, or treatment planning are typically regulated by the FDA as software as a medical device (SaMD). The FDA has authorized over 1,000 AI/ML-enabled medical devices, with the vast majority (76%) focused on radiology, a key area for cancer detection [31] [32].

Table 2: FDA Regulatory Pathways and AI/ML-Specific Considerations

| Pathway | Description | Relevance to AI/ML Cancer Detection Models |

|---|---|---|

| 510(k) Clearance | For devices "substantially equivalent" to a legally marketed predicate device [31]. | The most common pathway (96.4% of devices); suitable for incremental innovations in established domains like radiology AI [31]. |

| De Novo Classification | For novel devices with no predicate, but with low to moderate risk [31]. | Used for first-of-their-kind AI diagnostics (3.2% of devices); establishes a new predicate for future devices [31]. |

| Premarket Approval (PMA) | The most stringent pathway for high-risk (Class III) devices [31]. | Required for AI models guiding critical, irreversible treatment decisions (0.4% of devices) [31]. |

| Predetermined Change Control Plan (PCCP) | A proposed framework to allow safe and iterative modification of AI/ML models after deployment [31]. | Critical for "locked" and "adaptive" algorithms; enables continuous learning and improvement while maintaining oversight. Only 1.5% of approved devices reported a PCCP as of 2024 [31]. |

A significant challenge in this domain is transparency. A 2025 study evaluating FDA-reviewed AI/ML devices found that the average transparency score was low (3.3 out of 17), with over half of the devices not reporting any performance metric like sensitivity or specificity in their public summaries [31]. This highlights a gap between regulatory review and the information available to the scientific community for independent assessment.

Experimental Data and Validation Protocols

Performance Metrics for Regulatory Evaluation

To gain regulatory approval, ML models for cancer detection must demonstrate robust performance through rigorously designed clinical studies. The following table summarizes reported performance metrics for a range of FDA-cleared AI/ML devices, providing a benchmark for researchers.

Table 3: Reported Performance Metrics of FDA-Cleared AI/ML Medical Devices (Adapted from [31])

| Performance Metric | Reported Median (IQR) (%) | Frequency of Reporting in FDA Summaries (n=1012 devices) |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | 91.2 (85 - 94.6) | 23.9% |

| Specificity | 91.4 (86 - 95) | 21.7% |

| Area Under the ROC (AUROC) | 96.1 (89.4 - 97.4) | 10.9% |

| Positive Predictive Value (PPV) | 59.9 (34.6 - 76.1) | 6.5% |

| Negative Predictive Value (NPV) | 98.9 (96.1 - 99.3) | 5.3% |

| Accuracy | 91.7 (86.4 - 95.3) | 6.4% |

It is critical to note that nearly half (46.9%) of authorized devices did not report a clinical study at all, and 51.6% did not report any performance metric in their public summaries [31]. This underscores the importance of comprehensive and transparent reporting in model validation research.

Detailed Experimental Protocol for Model Validation

A protocol designed to satisfy both scientific and regulatory requirements should include the following key methodologies, drawn from successful regulatory submissions and best practices:

- Retrospective and Prospective Data Collection: While most studies (32.1%) are retrospective, prospective data collection (7.4%) provides stronger evidence for real-world performance [31]. A hybrid approach (1.1%) can balance speed and robustness.

- Dataset Characterization and Curation: Researchers must meticulously document dataset sources, sizes, and demographics. Only 23.7% of FDA-approved devices reported dataset demographics, a major transparency gap [31]. For GDPR compliance, the provenance and legal basis for all data must be documented.

- Clinical Validation Study: A key step is conducting a clinical study to evaluate the model's performance against the standard of care. The median sample size for such studies in FDA submissions is 306 patients (IQR 142-650) [31]. The study should be designed to test the model's intended use and its impact on clinical workflow and patient outcomes.

- Bias and Fairness Assessment: Models must be evaluated for performance across appropriate subgroups (e.g., age, sex, ethnicity). This is not only an ethical imperative but also a requirement under FDA's Good Machine Learning Practice (GMLP) principles and the EU AI Act for high-risk systems [26] [31].

- Privacy-Preserving Validation Techniques: To comply with data minimization principles, techniques like federated learning (training models across decentralized data without sharing it) and the use of synthetic data should be explored. Recent research, such as the DP-TimeGAN model, demonstrates the generation of realistic, longitudinal electronic health records with quantifiable privacy protections aligned with both HIPAA and GDPR [33].

Visualization of Regulatory Workflows

FDA Pathway for AI/ML Medical Devices

The following diagram illustrates the key decision points and pathways for bringing an AI/ML-based cancer detection model to market in the U.S.

FDA AI/ML Device Pathway

Integrated Data Governance for Clinical ML Research

This workflow outlines the integrated data governance considerations when managing patient data for model training under both HIPAA and GDPR.

Data Governance Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Navigating the regulatory landscape requires both methodological and technical tools. The following table details essential "research reagents" for validating ML models in a compliant manner.

Table 4: Essential Tools for Compliant ML Model Validation in Cancer Detection

| Tool / Solution | Function | Relevance to GDPR/HIPAA/FDA |

|---|---|---|

| Privacy-Preserving Synthetic Data (e.g., DP-TimeGAN) | Generates realistic, synthetic patient datasets with mathematical privacy guarantees (e.g., Differential Privacy) [33]. | Enables model development and testing without using real PHI/personal data, addressing data minimization and utility for research. |

| Federated Learning Platforms | A distributed ML approach where the model is trained across multiple decentralized data sources without moving or sharing the raw data [29]. | Mitigates cross-border data transfer issues under GDPR and reduces centralization of sensitive data, aiding compliance with both GDPR and HIPAA. |

| De-identification & Pseudonymization Tools | Software that automatically identifies and removes (de-identification) or replaces with a reversible token (pseudonymization) personal identifiers in datasets [30]. | Core to creating HIPAA-compliant de-identified datasets. Pseudonymization is a key security measure under GDPR, though it does not exempt data from the regulation. |

| Data Protection Impact Assessment (DPIA) Template | A structured tool to systematically identify and minimize the data protection risks of a project [29]. | A mandatory requirement under GDPR for high-risk processing, such as large-scale use of health data for ML. |

| Predetermined Change Control Plan (PCCP) Framework | A documented protocol outlining the planned modifications to an AI/ML model and the validation methods used to ensure those changes are safe and effective [31]. | A proposed framework by the FDA to manage the lifecycle of AI/ML devices, allowing for continuous improvement post-deployment. |

Methodologies in Action: Building and Applying Validated ML Models for Cancer Detection

The validation of machine learning models has become a cornerstone of modern cancer detection research, providing the rigorous methodology required to translate computational predictions into clinical insights. Among the diverse artificial intelligence architectures, Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs)—including their variant Long Short-Term Memory networks (LSTMs)—and hybrid models have emerged as particularly transformative. Each architecture offers distinct advantages aligned with the data modalities prevalent in oncology: CNNs excel at parsing spatial hierarchies in imaging data, RNNs/LSTMs capture temporal and sequential dependencies in genomic information, and hybrid models integrate multiple data types and algorithms to create more robust predictive systems. This guide provides a systematic comparison of these architectures, detailing their performance, experimental protocols, and implementation requirements to inform researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in selecting and validating appropriate models for specific oncological applications. The objective analysis presented herein is framed within the critical context of model validation, emphasizing reproducibility, performance metrics, and clinical applicability across various cancer types.

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) for Medical Imaging

Performance and Experimental Data

CNNs have demonstrated exceptional performance in analyzing medical images for cancer detection, classification, and segmentation. Their capacity to automatically learn hierarchical spatial features from pixel data makes them particularly suited for modalities like mammography, MRI, and histopathology. Recent studies validate their high accuracy across multiple imaging types and cancer domains.

Table 1: CNN Performance Across Cancer Imaging Modalities

| Cancer Type | Imaging Modality | Dataset(s) | Model Architecture | Key Performance Metrics | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast Cancer | Mammography | DDSM, MIAS, INbreast | Custom CNN | Accuracy: 99.2% (DDSM), 98.97% (MIAS), 99.43% (INbreast) | [34] |

| Breast Cancer | Ultrasound, MRI, Histopathology | Ultrasound, MRI, BreaKHis | Custom CNN | Accuracy: 98.00% (Ultrasound), 98.43% (MRI), 86.42% (BreaKHis) | [34] |

| Brain Tumors | MRI | Custom dataset (3,000+ images) | VGG, ResNet, EfficientNet, ConvNeXt, MobileNet | Best accuracy: 98.7%; MobileNet: 23.7 sec/epoch training time | [35] |

| Brain Tumors | MRI | Custom dataset (7,023 images) | CNN-TumorNet | Accuracy: 99.9% for tumor vs. non-tumor classification | [36] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Multimodal Breast Cancer Detection Framework [34]: This study developed a unified CNN framework capable of processing multiple imaging modalities within a single model. The methodology involved: (1) Data Acquisition and Preprocessing: Collecting images from several benchmark datasets (DDSM, MIAS, INbreast for mammography; additional datasets for ultrasound, MRI, and histopathology). Standardized preprocessing procedures were applied across all datasets, including resizing, normalization, and augmentation to ensure consistency. (2) Model Architecture and Training: Implementing a CNN architecture optimized to minimize overfitting through strategic design choices like dropout layers and batch normalization. The model was trained to perform binary classification (cancerous vs. non-cancerous) across all modalities. (3) Validation and Comparison: Evaluating the model on held-out test sets for each modality and comparing performance against leading state-of-the-art techniques using accuracy as the primary metric.

Brain Tumor Classification Study [35]: This research comprehensively analyzed CNN performance for brain tumor classification using MRI. The experimental protocol included: (1) Dataset Curation: Utilizing over 3,000 MRI images spanning three tumor types (gliomas, meningiomas, pituitary tumors) and non-tumorous images. (2) Architecture Comparison: Exploring recent deep architectures (VGG, ResNet, EfficientNet, ConvNeXt) alongside a custom CNN with convolutional layers, batch normalization, and max-pooling. (3) Training Methodologies: Assessing different approaches including training from scratch, data augmentation, transfer learning, and fine-tuning. Hyperparameters were optimized using separate validation sets. (4) Performance Evaluation: Measuring accuracy and computational efficiency (training time, image throughput) on independent test sets.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Materials for CNN Experiments in Oncology Imaging

| Reagent/Resource | Function in Experimental Protocol | Example Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Curated Medical Image Datasets | Model training and validation | DDSM, MIAS, INbreast (mammography); TCIA (MRI); BreaKHis (histopathology) |

| Deep Learning Frameworks | Model implementation and training | TensorFlow, Keras, PyTorch with GPU acceleration |

| Data Augmentation Tools | Dataset expansion and regularization | Rotation, flipping, scaling, contrast adjustment transforms |

| Transfer Learning Models | Pre-trained feature extractors | VGG, ResNet, EfficientNet weights pre-trained on ImageNet |

| GPU Computing Resources | Accelerated model training | NVIDIA Tesla V100, A100, or RTX series with CUDA support |

| Medical Image Preprocessing Libraries | Standardization of input data | SimpleITK, OpenCV, scikit-image for resizing, normalization |

RNNs/LSTMs for Genomic Sequences

Performance and Experimental Data

RNNs and their more sophisticated variants, particularly LSTMs and Gated Recurrent Units (GRUs), have shown significant promise in analyzing genomic sequences for cancer mutation prediction, transcription factor binding site identification, and oncogenic progression forecasting. Their ability to capture long-range dependencies in sequential data makes them naturally suited for genomic applications.

Table 3: RNN/LSTM Performance in Genomic Cancer Applications

| Application Domain | Data Source | Model Architecture | Key Performance Metrics | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oncogenic Mutation Progression | TCGA Database | RNN with LSTM units | Accuracy: >60%, ROC curves comparable to existing diagnostics | [37] |

| Transcription Factor Binding Site Prediction | ENCODE ChIP-seq data | Bidirectional GRU with k-mer embedding (KEGRU) | Superior AUC and APS compared to gkmSVM, DeepBind, CNN_ZH | [38] |

| Cancer Classification from Exome Sequences | Twenty exome datasets | Ensemble with MLPs | Weighted average accuracy: 82.91% | [39] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

RNN Framework for Mutation Progression [37]: This study developed an end-to-end framework for predicting cancer severity and mutation progression using RNNs. The methodology comprised: (1) Data Processing: Isolation of mutation sequences from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database. Implementation of a novel preprocessing algorithm to filter key mutations by mutation frequency, identifying a few hundred key driver mutations per cancer stage. (2) Network Module: Construction of an RNN with LSTM architectures to process mutation sequences and predict cancer severity. The model incorporated embeddings similar to language models but applied to cancer mutation sequences. (3) Result Processing and Treatment Recommendation: Using RNN predictions combined with information from preprocessing algorithms and drug-target databases to predict future mutations and recommend possible treatments.

KEGRU for TF Binding Site Prediction [38]: This research introduced KEGRU, a model combining Bidirectional GRU with k-mer embedding for predicting transcription factor binding sites. The experimental protocol included: (1) Sequence Representation: DNA sequences were divided into k-mer sequences with specified length and stride window, treating each k-mer as a word in a sentence. (2) Embedding Training: Pre-training word representation models using the word2vec algorithm on k-mer sequences. (3) Model Architecture: Constructing a deep bidirectional GRU model for feature learning and classification, using 125 TF binding sites ChIP-seq experiments from the ENCODE project. (4) Performance Validation: Comparing model performance against state-of-the-art methods (gkmSVM, DeepBind, CNN_ZH) using AUC and average precision score as metrics.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Materials for RNN/LSTM Experiments in Genomics

| Reagent/Resource | Function in Experimental Protocol | Example Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Genomic Databases | Source of sequence and mutation data | TCGA, ENCODE, SEER, NCBI SRA |

| Sequence Preprocessing Tools | K-mer segmentation and data cleaning | Biopython, custom Python scripts for k-mer generation |

| Embedding Algorithms | Sequence vectorization | word2vec, GloVe, specialized biological embedding methods |

| Specialized RNN Frameworks | Model implementation | TensorFlow, PyTorch with LSTM/GRU cell support |

| High-Performance Computing | Handling large genomic datasets | CPU cluster with high RAM for sequence processing |

| Genomic Annotation Databases | Functional interpretation of results | ENSEMBL, UCSC Genome Browser, dbSNP |

Hybrid Models for Comprehensive Cancer Analysis

Performance and Experimental Data

Hybrid models that integrate multiple algorithmic approaches or data modalities have emerged as powerful tools for addressing the multifaceted nature of cancer biology. These models combine the strengths of different architectures to overcome individual limitations and enhance predictive performance, particularly for complex tasks like survival prediction and multi-modal data integration.

Table 5: Hybrid Model Performance in Oncology Applications

| Application Domain | Cancer Type | Hybrid Architecture | Key Performance Metrics | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survival Prediction | Cervical Cancer | CoxPH with Elastic Net + Random Survival Forest | C-index: 0.82, IBS: 0.13, AUC-ROC: 0.84 | [40] [41] |

| Early Mortality Prediction | Hepatocellular Carcinoma | Ensemble of ANN, GBDT, XGBoost, DT, SVM | AUROC: 0.779 (internal), 0.764 (external), Brier score: 0.191 | [42] |

| Cancer Classification | Multiple Cancers | Ensemble with KNN, SVM, MLPs | Accuracy: 82.91% (increased to 92% with GAN/TVAE) | [39] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Hybrid Survival Model for Cervical Cancer [40] [41]: This research developed a hybrid survival model integrating traditional statistical approaches with machine learning for cervical cancer survival prediction. The methodology included: (1) Data Source and Preprocessing: Extraction of cervical cancer patient data from the SEER database (2013-2015) with preprocessing involving normalization, encoding, and handling missing values through multiple imputation. (2) Model Components: Implementation of two complementary models: Random Survival Forest (RSF) to capture non-linear interactions between covariates, and Cox Proportional Hazards (CoxPH) model with Elastic Net regularization for linear interpretability and feature selection. (3) Hybridization Strategy: Combination of predictions from both models using a weighted averaging approach based on linear regression weighting coefficients determined through cross-validation. (4) Validation: Assessment of model performance on an independent test set using concordance index (C-index), Integrated Brier Score (IBS), and AUC-ROC metrics.